Listerine

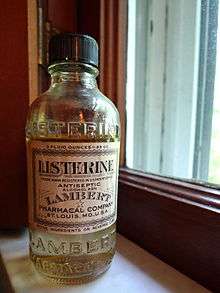

Listerine is a brand of antiseptic mouthwash product. It is promoted with the slogan "Kills germs that cause bad breath". Named after Joseph Lister, a pioneer of antiseptic surgery, Listerine was developed in 1879 by Joseph Lawrence, a chemist in St. Louis, Missouri.[1]

Various Listerine products in Canada | |

| Product type | Mouthwash, toothpaste, fluoride rinse, quick-dissolving strips, chewable tablets, breath spray, dental floss |

|---|---|

| Owner | McNeil Consumer Healthcare division of Johnson & Johnson |

| Country | United States |

| Introduced | 1914 |

| Related brands | Plax |

| Previous owners | Lambert Pharmacal Company Warner-Lambert Pfizer |

| Tagline | "Kills germs that cause bad breath" "Bring Out the Bold" |

| Website | www |

Originally marketed by the Lambert Pharmacal Company (which later became Warner-Lambert), Listerine has been manufactured and distributed by Johnson & Johnson since that company's acquisition of Pfizer's consumer healthcare division in late December 2006.

The Listerine brand name is also used in toothpaste, Listerine Whitening rinse, Listerine Fluoride rinse (Listerine Tooth Defense), Listerine SmartRinse (children's fluoride rinse), chewable tablets (Listerine Ready!) PocketPaks, and PocketMist. In September 2007, Listerine began selling its own brand of self-dissolving teeth-whitening strips.

History

Inspired by Louis Pasteur's ideas on microbial infection, the English doctor Joseph Lister demonstrated in 1865 that use of carbolic acid on surgical dressings would significantly reduce rates of post-surgical infection. Lister's work in turn inspired St. Louis-based doctor Joseph Lawrence to develop an alcohol-based formula for a surgical antiseptic which included eucalyptol, menthol, methyl salicylate, and thymol (Its exact composition is a trade secret). Lawrence named his antiseptic "Listerine" in honor of Lister.[2]

Lawrence hoped to promote Listerine's use as a general germicide as well as a surgical antiseptic, and licensed his formula to a local pharmacist named Jordan Wheat Lambert in 1881. Lambert subsequently started the Lambert Pharmacal Company, marketing Listerine.[2] Listerine was promoted to dentists for oral care in 1895[3] and was the first over-the-counter mouthwash sold in the United States, in 1914.[4] It became widely known and entered common household use after Jordan Wheat Lambert's son Gerard Lambert joined the company and promoted an aggressive marketing campaign.[2]

According to Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner's book Freakonomics:[5]

Listerine, for instance, was invented in the nineteenth century as powerful surgical antiseptic. It was later sold, in distilled form, as both a floor cleaner and a cure for gonorrhea. But it wasn't a runaway success until the 1920s, when it was pitched as a solution for "chronic halitosis" — a then obscure medical term for bad breath. Listerine's new ads featured forlorn young women and men, eager for marriage but turned off by their mate's rotten breath. "Can I be happy with him in spite of that?" one maiden asked herself. Until that time, bad breath was not conventionally considered such a catastrophe. But Listerine changed that. As the advertising scholar James B. Twitchell writes, "Listerine did not make mouthwash as much as it made halitosis." In just seven years, the company's revenues rose from $115,000 to more than $8 million.

In 1955, Lambert Pharmacal merged with New York-based Warner-Hudnut and became Warner-Lambert Pharmaceutical Company and incorporated in Delaware with its corporate headquarters in Morris Plains, New Jersey.[6] In 2000, Pfizer acquired Warner-Lambert.[7] Among Lambert's assets was the original land for Lambert-St. Louis International Airport.[8]

From 1921 until the mid-1970s, Listerine was also marketed as preventive and remedy for colds and sore throats. In 1976, the Federal Trade Commission ruled that these claims were misleading, and that Listerine had "no efficacy" at either preventing or alleviating the symptoms of sore throats and colds. Warner-Lambert was ordered to stop making the claims, and to include in the next $10.2 million worth of Listerine ads specific mention that "Listerine will not help prevent colds or sore throats or lessen their severity."[9] The advertisement run by Listerine added the preamble "contrary to prior advertising".[10]

For a short time, beginning in 1927, the Lambert Pharmaceutical Company marketed Listerine Cigarettes.[11][12]

From the 1930s into the 1950s, advertisements claimed that applying Listerine to the scalp could prevent "infectious dandruff".[13]

Listerine was packaged in a glass bottle inside a corrugated cardboard tube for nearly 80 years before the first revamps were made to the brand: in 1992, Cool Mint Listerine was introduced in addition to the original Listerine Antiseptic formula and, in 1994, both brands were introduced in plastic bottles for the first time. In 1995, FreshBurst was added,[14] then in 2003 Natural Citrus. In 2006 a new addition to the "less intense" variety, Vanilla Mint, was released. Nine different kinds of Listerine are on the market in the U.S. and elsewhere: Original, Cool Mint, FreshBurst, Natural Citrus, Naturals, Soft Mint (Vanilla Mint), UltraClean (formerly Advanced Listerine), Tooth Defense (mint shield), and Whitening pre-brush rinse (clean mint).

Composition

The active ingredients listed on Listerine packaging are essential oils which are menthol (mint) 0.042%, thymol (thyme) 0.064%, methyl salicylate (wintergreen) 0.06%, and eucalyptol (eucalyptus) 0.092%.[15] In combination all have an antiseptic effect and there is some thought that methyl salicylate may have an anti inflammatory effect as well.[16] Ethanol, which is toxic to bacteria at concentrations of 40%, is present in concentrations of 21.6% in the flavored product and 26.9% in the original gold Listerine Antiseptic.[17] At this concentration, the ethanol serves to dissolve the active ingredients.[18]

The addition of the active ingredients means the ethanol is considered to be undrinkable, known as denatured alcohol, and it is therefore not regulated as an alcoholic beverage in the United States. (Specially Denatured Alcohol Formula 38-B, specified in Title 27, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 21, Subpart D) However, consumption of mouthwash to obtain intoxication does occur, especially among alcoholics and underage drinkers.[19]

Safety

There has been concern that the use of alcohol-containing mouthwash such as Listerine may increase the risk of developing oral cancer.[20][21] As of 2010, 7 meta-analyses have found no connection between alcohol-containing mouthwashes and oral cancer, and 3 have found increased risk.[22] In January 2009, Andrew Penman, chief executive of The Cancer Council New South Wales, called for further research on the matter.[21] In a March 2009 brief, the American Dental Association said "the available evidence does not support a connection between oral cancer and alcohol-containing mouthrinse".[23] In 2009, Johnson and Johnson launched a new alcohol-free version of the product called Listerine Zero.[24]

On April 11, 2007, McNeil-PPC disclosed that there were potentially contaminants in all Listerine Agent Cool Blue products sold since its launch in 2006, and that all bottles were being recalled.[25] The recall affected some 4,000,000 bottles sold since that time.[26] According to the company, Listerine Agent Cool Blue is the only product affected by the contamination and no other products in the Listerine family were under recall.[25]

References

- Newton, David (2008). Trademarked : a history of well-known brands, from Aertex to Wright's Coal Tar. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0750945905.

- Hicks, Jesse. "A Fresh Breath". Thanks to Chemistry. Chemical Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on July 12, 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- "Prescribe Listerine for Patients". The Pacific Dental Journal. 5 (2): 58. 1895. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Casey, Wilson (2009). Firsts: Origins of Everyday Things That Changed the World. New York: Penguin. p. 155. ISBN 978-1101159460. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Levitt, Steven D.; Dubner, Stephen J. (2009). Freakonomics : A Rogue Economist Explores The Hidden Side Of Everything. New York: HarperCollins. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-06-073133-5. OCLC 502013083.

Note that previous editions of Freakonomics incorrectly described halitosis as a "faux medical term", which this Wikipedia article previously reflected. - "Warner-Hudnut, Inc. ( Early Warner-Lambert Company )". GoAntiques.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- "2000: Pfizer joins forces with Warner-Lambert". Pfizer. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- Mary Delach Leonard (Dec 25, 2016). "Lambert airport traces its history to an aviation visionary who knew how to sell mouthwash". St. Louis Public Radio. Archived from the original on 2017-02-18. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- "Three by the FTC". Time. Jan 5, 1976. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- Business Its Legal, Ethical, and Global Environment by Marianne M. Jennings 8th edition page 324, Given these safeguards, we believe the preamble "Contrary to prior advertising" is not necessary.

- Gardiner, Phillip (2004). "The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States" (PDF). Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 6: S55–65. doi:10.1080/14622200310001649478. PMID 14982709.

- "LISTERINE Cigarettes". Tobacco Documents Online. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- Lambert Pharmacal (1930). "Listerine gets rid of dandruff". Popular Science. 116 (5): 17. ISSN 0161-7370.

- "Article: Warner-Lambert reenters the dentrifice business". Chain Drug Review. 1995-07-31. Archived from the original on 2013-09-26. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- Materials Safety Data Sheet for Listerine Antiseptic Mouthwash, Original-05/22/2008

- Mason, L.; Moore, R. A.; Edwards, J. E.; McQuay, H. J.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P. J. (2004). "Systematic review of efficacy of topical rubefacients containing salicylates for the treatment of acute and chronic pain". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 328 (7446): 995. doi:10.1136/bmj.38040.607141.EE. PMC 404501. PMID 15033879.

- Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. Seymour, Stanton, & Block. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Jan 1, 2001 § pp 238

- "Alcohol". Listerine Professional. Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- Cathleen Terhune Alty (March 12, 2014). "Do you want that mouthwash straight up or on the rocks?". RDH.

- McCullough, Michael; Farah, C.S. (December 2008). "The role of alcohol in oral carcinogenesis with particular reference to alcohol-containing mouthwashes". Australian Dental Journal. 53 (4): 302–305. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.00070.x. PMID 19133944. Archived from the original on 2012-12-16. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- Weaver, Clair (January 10, 2009). "Mouthwash linked to cancer". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- La Vecchia, C (2009). "Mouthwash and oral cancer risk: An update". Oral Oncology. 45 (3): 198–200. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.08.012. PMID 18952488.

- Science brief on alcohol-containing mouthrinses and oral cancer, American Dental Association, March 2009

- Listerine cancer claim triggers court battle, The Guardian, 27 August 2011

- "McNeil-PPC, Inc. today issues voluntary nationwide consumer recall of Listerine Agent Cool Blue plaque-detecting rinse products" (Press release). McNeil-PPC. 2007-04-11. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- "Contamination prompts J&J recall of Listerine Agent Cool Blue plaque-detecting rinse". NBC News. Associated Press. 2007-04-12. Retrieved Aug 15, 2014.