Gender bias in medical diagnosis

Gender-biased diagnosing is the idea that medical and psychological diagnosis are influenced by the gender of the patient. Several studies have found evidence of differential diagnosis for patients with similar ailments but of different sexes[1]. Female patients face discrimination through the denial of treatment or misclassification of diagnosis as a result of not being taken seriously due to stereotypes and gender bias. According to traditional medical studies, most of these medical studies were done on men thus overlooking many issues that were related to women's health. This topic alone sparked controversy and brought about question to the medical standard of our time. Research that was done on diseases that affected women more were less funded than those diseases that affected men and women equally.[2]

History

The earliest traces of gender-biased diagnosing could be found within the disproportionate diagnosis of women with hysteria as early as 4000 years ago.[3] Hysteria was earlier defined as excessive emotions. Within a medical setting, this hysteria translated to the over exaggeration of symptoms and ailments. Because traditional gender roles usually place women at a subordinate position compared to men, the medical industry, which is seen as powerful, has historically been dominated by men.[4] This has caused for a misdiagnosis within females due to the large male workers who would fall for gender stereotypes of females being more emotion, and sensitive. These gender roles and gender biases may have also contributed to why pain associated with experiences unique to women, like childbirth and menstruation, were dismissed or mistreated. In 1948 some women volunteered to take part in an experiment designed to quantify pain in laboring women. During their labor, their hands were burned in other to try to measure their pain threshold with the option to quit at any time and to receive treatment. During childbirth and as it kept progressing, the females were unable to feel an increase in pain insomuch as many of them received second degree burns without realizing.[5]

In a 1979 observational study, 104 women and men gave responses to their health in 5 areas: “back pain, headaches, dizziness, chest pain, and fatigue". When receiving these complaints, it was seen that doctors gave extensive checkups to men more often than women with similar complaints, supporting that female patients tend to be taken less seriously than their male counterparts with regard to receiving medical illnesses.[6]

In 1990, the National Institutes of Health recognized the disparities in research of disease in men and when. At this time the Office of Research on Women’s Health was created. A large part of its purpose is to raise awareness of sex affects disease and treatments.[5][7] In 1991 and 1992 recognition that a 'glass ceiling' existed showcased that it was preventing female clinicians from being promoted.[8][9] In 1994 the FDA created an Office of Women’s Health by congressional mandate.[10]

As for the Women's Health Equity Act that was passed in 1993, this Act gave women the chance to participate in medical studies and examine the gender differences.[11] Before the Women's Health Equity Act was introduced there was no research done on infertility, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer which were essential to women's health.[12]

Clinical trials and research

The approach to women shifted from paternalistic protection to access in the early 1980s as AIDS activists like ACT UP and women's groups challenged ways that drugs were developed. The NIH responded with policy changes in 1986, but a Government Accountability Office report in 1990 found that women were still being excluded from clinical research. That report, the appointment of Bernadine Healy as the first woman to lead the NIH, and the realization that important clinical trials had excluded women led to the creation of the Women's Health Initiative at the NIH and to the federal legislation, the 1993 National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act, which mandated that women and minorities be included in NIH-funded research.[13][14][15] The initial large studies on the use of low-dose aspirin to prevent heart attacks that were published in the 1970s and 1980s are often cited as examples of clinical trials that included only men, but from which people drew general conclusions that did not hold true for women.[15][16][17] In 1993 the FDA reversed its 1977 guidance, and included in the new guidance a statement that the former restriction was “rigid and paternalistic, leaving virtually no room for the exercise of judgment by responsible research subjects, physician investigators, and investigational review boards (IRBs)”.[18]

The National Academy of Medicine published a report called "Women and Health Research: Ethical and Legal Issues of Including Women in Clinical Studies" in 1994[13] and another report in 2001 called "Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter?” which each urged including women in clinical trials and running analyses on subpopulations by sex.[18][19]

Although guidelines have been introduced, sex bias remains an issue. A 2001 meta-analysis found that of 120 trials published in the New England Journal of Medicine, on average just 24.6 percent of participants enrolled were women. In addition, the same 2001 meta-analysis found that 14 percent of the trials included sex specific data analysis

A 2005 review by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use found that regulation in the US, Europe, and Japan required that clinical trials should reflect the population to whom an intervention will be given, and found that clinical trials that had been submitted to agencies were generally complying with those regulations.[20]

A review of NIH-funded studies (not necessarily submitted to regulatory agencies) published between 1995 and 2010 found that they had an "average enrollment of 37% (±6% standard deviation [SD]) women, at an increasing rate over the years. Only 28% of the publications either made some reference to sex/gender-specific results in the text or provided detailed results including sex/gender-specific estimates of effect or tests of interaction."[21]

The FDA published a study of the 30 sets of clinical trial data submitted after 2011, and found that for all of them, information by sex was available in public documents, and that almost all of them included subanalyses by sex.[18]

As of 2015, recruiting women to participate in clinical trials remained a challenge.[22]

In 2018 the US FDA released draft guidelines for inclusion of pregnant women in clinical trials.[23][24]

In a 2019 meta-analysis it was reported that 36.41 percent of participants in 40 trials for anti-psychotic drugs were women.[25]

Medical diagnosis

The possibility of gender differences in experiences of pain has led to a discrepancy in treating female patients' pain over that of male patients [26]. The phenomenon may affect physical diagnosis. Women are more likely to be given a diagnosis of psychosomatic nature for a physical ailment than men, despite presenting with similar symptoms. Women sometimes have trouble being taken seriously by physicians when suffering from medically unexplained illness, and report difficulty receiving appropriate medical care for their illnesses because doctors repeatedly diagnose their physical complaints as related to psychiatric problems[27] or simply related to female's menstrual cycle. Clinical offices that rely on healthcare routines become less distinct due to biased medical knowledge of gender. There is a distinct differentiation between gender and sex in the medical sense. Because gender is the societal construction of what femininity and masculinity is, whereas, sex is the biological aspect that defines the dichotomy of female and male. The way of lifestyle and the place in society are often considered when diagnosing patients.[28]

Men and women are biologically different. They differ in the mechanical workings of their hearts and in their lung capacities, resulting in women being 20-70% more likely to develop lung cancer.[29] The differences between men and women are also seen at the cellular level. For example, the ways immune cells convey pain signals are different in men and women.[30] As a result of these biological differences, men and women react to certain drugs and medical treatments differently.[29] One example is opioids. When using opioids for pain relief, women and men have different reactions. Surveys of the literature also conclude that there is a need for more clinical trials that study the gender specific response to opioids.[31]

Although there is evidence pointing to the biological difference between men and women, historically women have been excluded from clinical trials and men have been used as the standard.[32] This male standard has its roots in ancient Greece, where the female body was viewed as a mutilated version of the male body.[32] However, the male bias was furthered in the United States in the 1950s and 60s after the FDA issued guidelines excluding women of childbearing potential from trials to avoid any risk to a potential fetus.[33][13] Additionally, the thalidomide tragedy led the FDA to issue regulations in 1977 recommending that women should be excluded from participating in Phase I and Phase II studies in the US.[18] Studies also excluded women for other reasons including that women were more expensive to use as test subjects because of fluctuating hormone levels. The assumption that women would have the same reaction to the treatments as men was also used to justify excluding women from clinical trials.[29]

Psychological diagnosis

There was an example of gender bias in the psychiatric field as well, Hamburg notes that, "psychiatrists would diagnose women with depression and then, eventually psychiatrists would begin to assume that women were more depressed than men due to the fact that the patients that were examined by the psychiatrists were women and they had similar symptoms. As for the men, they were diagnosed with drug or alcohol problems and they were thrown out of the study."[28] There is a suggestion that assumptions regarding gender specific behavioural characteristics can lead to a diagnostic system which is biased.[34] The issue of gender bias with regard to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) personality disorder criteria has been controversial and widely debated. The fourth DSM (4th ed., text revision; DSM–IV–TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) makes no explicit statement regarding gender bias among the ten personality disorders (PDs), but it does state that six PDs (antisocial, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizotypal, schizoid) are more frequently found in men. Three others (borderline, histrionic, dependent) are more frequent in women. Avoidant is equally common in men and women.[35]

There are many ways to interpret differential prevalence rates as a function of gender. Some critics have argued that they are an artifact of gender bias. In other words, the PD criteria assume unfairly that stereotypical female characteristics are pathological. The results of this study conclude with no indication of gender-biased criteria in the borderline, histrionic, and dependent PDs. This is in contrast with what is predicted by critics of these disorders, who suggest they are biased against women. It is possible, however, that other sources of bias, including assessment and clinical bias, are still at work in relation to these disorders. The results do show that the group means are higher in women than in men, an expected result considering the higher prevalence rate of these disorders for women.[35]

The original purpose of the DSM–IV was to provide an accurate classification of psychopathology, not to develop a diagnostic system that will, democratically, diagnose as many men with a personality disorder as women". However, if the criteria are to serve equally as indicators of disorder for both men and women, it will be important to establish that the implications of these criteria for functional impairment are comparable for both sexes. Whereas it is plausible that there are gender-specific expressions of these disorders, DSM–IV criteria that function differentially for men and women can systematically over-pathologize or under-represent mental illness in a particular gender. The present study is limited by the investigation of only four personality disorders and the lack of inclusion of additional diagnoses that have also been controversial in the gender bias debate (such as dependent and histrionic personality disorders), although it offers a clearly articulated methodology for studying this possibility. In addition, it provides an examination of a clinical sample of substantial size and uses functional assessments that cut across multiple functional domains and multiple assessment methods. Our results indicate that BPD criteria showed some evidence of differential functioning between genders on global functioning, although there is little evidence of sex bias within the diagnostic criteria for avoidant, schizotypal, or obsessive–compulsive personality disorders. Further investigation and validation across sexes for those disorders would be an important direction of future research.[36]

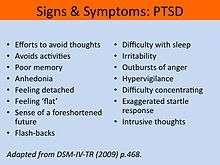

Considerable evidence indicates a prominent role for trauma-related cognitions in the development and maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. The present study utilized regression analysis to examine the unique relationships between various trauma-related cognitions and PTSD symptoms after controlling for gender and measures of general affective distress in a large sample of trauma-exposed college students. In terms of trauma-related cognitions, only negative cognitions about the self were related to PTSD symptom severity. Gender and anxiety symptoms were also related to PTSD symptom severity. Theoretical implications of the results are consistent with previous studies on the relationship between PTSD and negative cognitions, the self, world, and blame subscales of the PTCI were significantly related to PTSD symptoms. The study correlations indicated that increased negative trauma-related cognitions were related to more severe PTSD symptoms. Also consistent with previous reports, correlations also indicated that gender was related to PTSD symptom severity, such that women had more severe PTSD symptoms. PTSD symptom severity was also positively related to depression, anxiety, and stress reactivity.[37]

Distinguishing between borderline personality disorder (BPD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is often challenging, especially when the client has experienced a trauma such as childhood sexual abuse (CSA), which is strongly linked to both disorders. Although the individual diagnostic criteria for these two disorders do not overlap substantially, patients with either of these disorders can display similar clinical pictures. Both patients with BPD and PTSD may present as aggressive toward self or others, irritable, unable to tolerate emotional extremes, dysphoric, feeling empty or dead, and highly reactive to mild stressors. Despite having similar clinical pictures, PTSD and BPD are regarded differently by many clinicians. Results from a 2009 study concluded that patient gender does not affect diagnosis. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that women are not more likely to be given the BPD diagnosis, all else being equal, though it contradicts other findings from studies that have used similar case vignettes. Nor did the data support an effect of clinician gender or age on diagnosis.[38]

A 2012 study examined gender-specific associations between trauma cognitions, alcohol cravings and alcohol-related consequences in individuals with dually diagnosed PTSD and alcohol dependence (AD). Participants had entered a treatment study for concurrent PTSD and AD; baseline information was collected from participants about PTSD-related cognitions in three areas: (a) Negative Cognitions About Self, (b) Negative Cognitions About the World, and (c) Self-Blame. Information was also collected on two aspects of AD: alcohol cravings and consequences of AD. Gender differences were examined while controlling for PTSD severity. The results indicate that Negative Cognitions About Self are significantly related to alcohol cravings in men but not women, and that interpersonal consequences of AD are significantly related to Self-Blame in women but not in men. These findings suggest that for individuals with comorbid PTSD and AD, psychotherapeutic interventions that focus on reducing trauma-related cognitions are likely to reduce alcohol cravings in men and relational problems in women.[39]

Female patients

Female patients are often treated differently from men. Women have been described in studies and in narratives as emotional and hysterical.[40] Historically, women's health has been called "bikini medicine", which is why clinical research specifically for women were limited to only focusing on breasts and reproductive organs. Aside from these research focuses, clinical research mainly used male subjects, but apply results to both genders. Because of this, some physicians assume that women should be assessed and receive identical treatments as men. Narratives include the reporting that women's complaints are considered exaggerated and may be assumed to be invalid.[41][42] Because of this women are often subsequently are referred to psychiatrists for treatment.[41] The tendency of treating pain in women with antidepressants exposes the women to developing side effects to medication that they might not even need.[43] The report of medical concerns by women are more likely to be discounted, misdiagnosed, ignored and assumed to be psychosomatic.[40][41][43][44] One observer has stated that, "different forms of female suffering are minimized, mocked, coaxed into silence."[42] There are those that disagree with this characterization.[45][46]

Clinicians are not as likely to assess women for substance abuse as often as they assess men. They also tend to miss signs of substance addiction in women. Women are not as likely as men to be assessed for alcohol abuse. Out of those women who are found to have an alcohol problem, they were found to be less likely to be referred for treatment. Those women in the childbearing years are prescribed more prescription medications than men. It is generally more common for women to be prescribed antipsychotics and opioids.[47]

Women report feeling like they were 'silly' by male physicians but female physicians were more sensitive and preferred.[40] In a study of multiple men, women, and married couples, it was observed that men's complaints about physical health were evaluated more in depth than women's.[48]

Sex-selective abortion is the medical procedure or treatment that terminates a pregnancy when the baby is an undesired gender. The abortion of female fetuses is most common in areas where the culture values male children over females.[49] [50][51]

Sex selective abortion has been heavily utilized in numerous Asian countries. A British medical journal stated: "Compared with the normal ratio of about 95 girls being born per 100 boys (which is what we observe in Europe and North America), Singapore and Taiwan have 92, South Korea 88, and China a mere 86 girls born per 100 boys."[52]

When individuals encounter the medical field, many are in vulnerable states in their lives, whether that be because of illness, injury, death, etc. Both men and women experience this vulnerability and must entrust their bodies and lives into the hands of practitioners. Men and women could still have varying outcomes and repercussions to mistreatment within this system. Specifically for women, there is a strong association between their physical form and their femininity. Mistreatment of a female’s body, may not only pose a threat to their life, but also their social acceptance. Medical industry seeks to fix “abnormalities” within the body, and in that way practitioners may be reinforcing stereotypes. In her book, The Cancer Journals, Audre Lorde speaks about her unpleasant experiences as a breast cancer patient and her struggle towards finding the strength within after undergoing a mastectomy. Some women are given the option to use prosthesis, but Lorde highlights that this "treatment" aligns with the idea that perfection of the female body must be essential to the female identity.[53]

Avoiding gender bias

In order to avoid gender bias in medical diagnosing, researchers should conduct all studies with both male and female subjects in their samples. [54] Healthcare workers should not assume all men and women are the same, even if they display similar symptoms. In a study done to analyze gender bias, a physician in the research sample stated, '"I am solely a professional, neutral and genderless"'. While a seemingly positive statement, this kind of thought process can ultimately lead to gender biasing because it fails to note the real differences between men and women that must be taken into account when diagnosing a patient. [55] Other ways to avoid gender bias includes diagnostic checklists which help to increase accuracy, evidenced-based assessments and facilitation of informed choices. [56]

See also

- Gender-bias in medical diagnosis

- Reverse sexism

- Men in nursing

- Lateral violence

- Women in medicine

- Gender disparities in health

- Occupational sexism

- Women's health

- Female hysteria

References

- Spector, Nancy D.; Overholser, Barbara (2019-06-28). "Examining Gender Disparity in Medicine and Setting a Course Forward". JAMA Network Open. 2 (6): e196484. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6484. ISSN 2574-3805. PMID 31251371.

- Trechak A (1999). "On cultural and gender bias in medical diagnosis". Multicultural Education. 7 (2): 41.

- Tasca, Cecelia; Rapetti, Mariangela; Fadda, Bianca; Carta, Mauro (2012). "Women And Hysteria In The History Of Mental Health". Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 8: 110–119. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010110. PMC 3480686. PMID 23115576.

- "Women in medicine". Brought to Life.

- Molly Caldwell, Crosby (May 2, 2014). "Your Gender Determines the Quality of Your Healthcare (But There's Hope For the Future)". Verily Magazine.

- Armitage, K. J., L. J. Schneiderman, and R. A. Bass. “Response of Physicians to Medical Complaints in Men and Women.” JAMA 241, no. 20 (May 18, 1979): 2186–87.

- Aithal N (2017-04-02). "Sexism In Medicine Needs A Checkup". Huffington Post.

- Madsen MK, Blide LA (November 1992). "Professional advancement of women in health care management: a conceptual model". Topics in Health Information Management. 13 (2): 45–55. PMID 10122424.

- Wiggins C (3 September 1991). "Female healthcare managers and the glass ceiling. The obstacles and opportunities for women in management". Hospital Topics. 69 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1080/00185868.1991.9948448. PMID 10109490.

- Liu KA, Mager NA (2016). "Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications". Pharmacy Practice. 14 (1): 708. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708. PMC 4800017. PMID 27011778.

- WOMEN'S HEALTH EQUITY ACT of 1993. Congressional Record Daily Edition. n.p.: 1993.

- THE WOMEN'S HEALTH EQUITY ACT of 1991. Congressional Record Daily Edition. n.p.: 1991.

- Institute of Medicine (1994). "Executive Summary". In Mastroianni AC, Faden R, Federman D (eds.). Women and Health Research: Ethical and Legal Issues of Including Women in Clinical Studies, Volume 1. The National Academy Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-309-04992-4.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (1990). National Institutes of Health: Problems in Implementing Policy on Women in Study Populations.

- Schiebinger L (October 2003). "Women's health and clinical trials". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 112 (7): 973–7. doi:10.1172/JCI19993. PMC 198535. PMID 14523031.

- "Regular aspirin intake and acute myocardial infarction". British Medical Journal. 1 (5905): 440–3. March 1974. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5905.440. PMC 1633212. PMID 4816857.

- Elwood PC, Cochrane AL, Burr ML, Sweetnam PM, Williams G, Welsby E, Hughes SJ, Renton R (March 1974). "A randomized controlled trial of acetyl salicylic acid in the secondary prevention of mortality from myocardial infarction". British Medical Journal. 1 (5905): 436–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5905.436. PMC 1633246. PMID 4593555.

- Liu KA, Mager NA (2016). "Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications". Pharmacy Practice. 14 (1): 708. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708. PMC 4800017. PMID 27011778.

- Institute of Medicine (2001). Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter?. National Academy Press. ISBN 9780309072816.

- ICH (5 January 2005). "Gender Considerations in the Conduct of Clinical Trials (EMEA/CHMP/3916/2005)" (PDF). EMA.

- Foulkes MA (June 2011). "After inclusion, information and inference: reporting on clinical trials results after 15 years of monitoring inclusion of women". Journal of Women's Health. 20 (6): 829–36. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2527. PMID 21671773.

- Pal, Somnath (2015). "Inclusion of Women in Clinical Trials of New Drugs and Devices". US Pharm. 40 (10): 21.

- Dotinga, Randy (April 9, 2018). "Pregnant women in clinical trials: FDA questions how to include them". Ob.Gyn. News.

- "Pregnant Women: Scientific and Ethical Considerations for Inclusion in Clinical Trials Guidance for Industry" (PDF). FDA. April 2018.

- Santos-Casado M, García-Avello A (2019). "Systematic Review of Gender Bias in the Clinical Trials of New Long-Acting Antipsychotic Drugs". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 39 (3): 264–272. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001041. PMID 30939594.

- Wiggins, C. (1995). "Barriers to women's career attainment". Journal of Health and Human Services Administration. 17 (3): 368–78. ISSN 1079-3739. PMID 10153076.

- Llorca-Bofí, Vicent; Illán-Gala, Ignacio; Blesa, Rafael (2019-09-11). "Sex-related differences in the clinical diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia". MedRxiv: 19005702. doi:10.1101/19005702.

- Hamberg K (May 2008). "Gender bias in medicine". Women's Health (London, England). 4 (3): 237–43. doi:10.2217/17455057.4.3.237. PMID 19072473.

- Liu KA, Mager NA (2016-03-31). "Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications". Pharmacy Practice. 14 (1): 708. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708. PMC 4800017. PMID 27011778.

- Dusheck J. "Women's immune system genes operate differently from men's". News Center. Stanford Medicine. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- Pisanu C, Franconi F, Gessa GL, Mameli S, Pisanu GM, Campesi I, et al. (September 2019). "Sex differences in the response to opioids for pain relief: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Pharmacological Research. 148: 104447. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104447. PMID 31499196.

- Criado-Perez, Caroline (2019-03-12). Invisible women : data bias in a world designed for men. New York. ISBN 9781419729072. OCLC 1048941266.

- Commissioner, Office of the (2019-06-04). "Regulations, Guidance, and Reports related to Women's Health". FDA.

- Maddux JE, Winstead BA (2005). Psychopathology: foundations for a contemporary understanding. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 0-8058-4077-X. Retrieved November 2011

- Jane JS, Oltmanns TF, South SC, Turkheimer E (February 2007). "Gender bias in diagnostic criteria for personality disorders: an item response theory analysis". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 116 (1): 166–75. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.166. PMC 4372614. PMID 17324027.

- Boggs CD, Morey LC, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, et al. (December 2005). "Differential impairment as an indicator of sex bias in DSM-IV criteria for four personality disorders". Psychological Assessment. 17 (4): 492–6. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.492. PMID 16393017.

- Moser JS, Hajcak G, Simons RF, Foa EB (2007). "Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in trauma-exposed college students: the role of trauma-related cognitions, gender, and negative affect". Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 21 (8): 1039–49. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.009. PMC 2169512. PMID 17270389.

- Woodward HE, Taft CT, Gordon RA, Meis LA (December 2009). "Clinician bias in the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder". Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 1 (4): 282–290. doi:10.1037/a0017944.

- Jayawickreme N, Yasinski C, Williams M, Foa EB (March 2012). "Gender-specific associations between trauma cognitions, alcohol cravings, and alcohol-related consequences in individuals with comorbid PTSD and alcohol dependence" (PDF). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 26 (1): 13–9. doi:10.1037/a0023363. PMC 3213324. PMID 21480680.

- Aithal N (2017-04-02). "Sexism In Medicine Needs A Checkup". Huffington Post.

- Adler KW (25 April 2017). "Women Are Dying Because Doctors Treat Us Like Men". Marie Claire.

- Fassler J (15 October 2015). "How Doctors Take Women's Pain Less Seriously". Atlantic.

- Edwards, Laurie (16 March 2013). "Women and the Treatment of Pain". The New York Times.

- Chemaly, Soraya (23 June 2015). "How Sexism Affects Women's Health Every Day - Role Reboot". Role Reboot.

- Boynes-Shuck, Ashley (January 31, 2017). "Is There a Gender Bias Against Female Pain Patients?". Healthline.

- Molly Caldwell, Crosby (May 2, 2014). "Your Gender Determines the Quality of Your Healthcare (But There's Hope For the Future)". Verily Magazine.

- Terplan M (August 2017). "Women and the opioid crisis: historical context and public health solutions". Fertility and Sterility. 108 (2): 195–199. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.007. PMID 28697909.

- Armitage, K. J., L. J. Schneiderman, and R. A. Bass. “Response of Physicians to Medical Complaints in Men and Women.” JAMA 241, no. 20 (May 18, 1979): 2186–87.

- Goodkind D (1999-01-01). "Should prenatal sex selection be restricted? Ethical questions and their implications for research and policy". Population Studies. 53 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/00324720308069.

- A. Gettis, J. Getis, and J. D. Fellmann (2004). Introduction to Geography, Ninth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 200. ISBN 0-07-252183-X

- Canadian Medical Association Journal (15 March 2011). "The impact of sex selection and abortion in China, India and South Korea". ScienceDaily. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- Sen, Amartya (December 6, 2003). "Missing Women—revisited: Reduction in Female Mortality Has Been Counterbalanced by Sex Selective Abortions". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 327 (7427): 1297. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1297. PMC 286281. PMID 14656808.

- Lorde, Audre (1997). The Cancer Journals. San Francisco.

- Ruiz MT, Verbrugge LM (April 1997). "A two way view of gender bias in medicine". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 51 (2): 106–9. doi:10.1136/jech.51.2.106. PMC 1060427. PMID 9196634.

- Risberg G, Johansson EE, Hamberg K (August 2009). "A theoretical model for analysing gender bias in medicine". International Journal for Equity in Health. 8: 28. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-8-28. PMC 2731093. PMID 19646289.

- Skopp, Nancy A. "Do Gender Stereotypes Influence Mental Health Diagnosis and Treatment in the Military?". Psychological Health Center of Excellence. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

Further reading

- Smith EC (Spring 2011). "Gender-biased Diagnosing, the Consequences of Psychosomatic Misdiagnosis and 'Doing Credibility". Sociology Student Scholarship. Paper 5. Occidental College.

- Munch S (2004). "Gender-biased diagnosing of women's medical complaints:contributions of feminist thought, 1970-1995". Women & Health. 40 (1): 101–21. doi:10.1300/J013v40n01_06. PMID 15778134.