Epidemiology of pneumonia

Pneumonia is a common illness affecting approximately 450 million people a year and occurring in all parts of the world.[2] It is a major cause of death among all age groups, resulting in 1.4 million deaths in 2010 (7% of the world's yearly total) and was the 4th leading cause of death in the world in 2016, resulting in 3.0 million deaths worldwide.[2][3] Pneumonia is a type of lower respiratory tract infection, and is also the most deadly communicable disease as of 2016.[3] Rates are greatest in children less than five and adults older than 75 years of age.[2] It occurs about five times more frequently in the developing world versus the developed world.[2] Viral pneumonia accounts for about 200 million cases.[2]

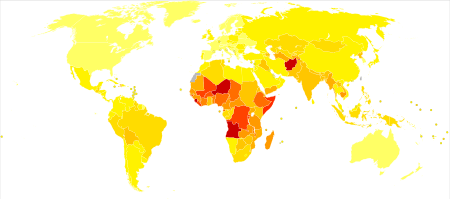

|

no data

<100

100-700

700-1400

1400-2100

2100-2800

2800-3500

|

3500-4200

4200-4900

4900-5600

5600-6300

6300-7000

>7000

|

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

Hospital-acquired pneumonia is pneumonia that is acquired in a hospital setting at least 48 hours after being admitted. Pneumonia the second most common hospital-acquired disease, while also being the leading cause of death among hospital-acquired infections. Hospital-acquired pneumonia is also seen to be the cause for nearly half of all the antibiotics taken within hospitals worldwide.[4]

A sub-type of hospital-acquired pneumonia, known as ventilator-associated pneumonia, is described as pneumonia acquired more than 48 hours after an endotracheal intubation procedure was performed. It is also seen to be the most common infection in intensive care units (ICUs), making up around 70-80% of the cases of hospital-acquired pneumonia in ICUs. The primary pathogen that can cause hospital-acquired pneumonia is dependent on the geographical location but overall, it was found that six most common bacteria that caused most hospital-acquired pneumonia cases were S. aureus, P. aeurginosa, Klebsiella species, E. coli, Acinetobacter species, and Enterobacter species. While the majority of these pathogens are bacteria, it is possible for multiple pathogens to infect at once and cause pneumonia.[4]

Children

In 2008 pneumonia occurred in approximately 156 million children (151 million in the developing world and 5 million in the developed world).[2] It caused in 1.6 million deaths or 28–34% of all deaths in those under five years of age of which 95% occur in the developing world.[2][5] Countries with the greatest burden of disease include: India (43 million), China (21 million) and Pakistan (10 million).[6]

Children in developing countries are at a significantly higher risk for developing pneumonia because malnutrition, overcrowding, and the lack of proper housing are prevalent risk factors. Other illnesses can also worsen the chances for developing pneumonia, such as malaria which is commonly seen in Africa and South Asia. Overall, the most determining risk factors for developing pneumonia among children in developing countries are age and the season. Children under 1 year of age are more at risk, and children overall are more at risk during rainy/wet seasons. S. pneumoniae appears to be the most prominent cause of infection, although it's unclear as to whether bacterial and viral co-infection plays a larger role in infecting children.[7]

It is the leading cause of death among children in low income countries.[2] Many of these deaths occur in the newborn period. The World Health Organization estimates that one in three newborn infant deaths are due to pneumonia.[8] Approximately half of these cases and deaths are theoretically preventable, being caused by the bacteria for which an effective vaccine is available.[9]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the annual incidence rate of pneumonia is approximately 6 cases per 1000 people in individuals aged 18–39 years. For those over 75 years of age, the incidence rate rises to 75 cases per 1000 people. Roughly 20–40% of individuals who contract pneumonia require hospital admission, with between 5–15% of these admitted to a critical care unit. The case fatality rate in the UK is around 5–10%.[10]

United States

In the United States, community-acquired pneumonia affects 5.6 million people per year, and ranks 6th among leading causes of death.[11] In 2009, there were approximately 1.86 million emergency department encounters for pneumonia in the United States.[12] In 2011, pneumonia was the second-most common reason for hospitalization in the U.S., with approximately 1.1 million stays—a rate of 36 stays per 10,000 population.[13]

Pneumonia was one of the top ten most expensive conditions seen during inpatient hospitalizations in the U.S. in 2011, with an aggregate cost of nearly $10.6 billion for 1.1 million stays.[14] In 2012, a study of Medicaid-covered and uninsured hospital stays in the United States in 2012, pneumonia was the second most common diagnosis for Medicaid-covered and uninsured hospital stays in the United States (behind mood disorders, at 3.7% for Medicaid stays and 2.4% for uninsured stays).[15]

Other population groups

More cases of community acquired pneumonia occur during the winter months than at other times of the year. Pneumonia occurs more commonly in males than in females, and more often among Blacks than Caucasians, partly due to quantitative differences in synthesizing Vitamin D after exposure to sunlight.[16]

Individuals with underlying chronic illnesses, such as Alzheimer's disease, cystic fibrosis, emphysema, and immune system problems as well as tobacco smokers, alcoholics, and individuals who are hospitalized for any reason, are at significantly increased risk of contracting, and having repeated bouts of, pneumonia.[16]

References

- "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization (WHO). 2004. Retrieved 11 Nov 2009.

- Ruuskanen O, Lahti E, Jennings LC, Murdoch DR (April 2011). "Viral pneumonia". Lancet. 377 (9773): 1264–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. PMID 21435708.

- "The top 10 causes of death". www.who.int. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- Cilloniz C, Martin-Loeches I, Garcia-Vidal C, San Jose A, Torres A (December 2016). "Microbial Etiology of Pneumonia: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Resistance Patterns". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (12): 2120. doi:10.3390/ijms17122120. PMC 5187920. PMID 27999274.

- Singh V, Aneja S (March 2011). "Pneumonia - management in the developing world". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 12 (1): 52–9. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2010.09.011. PMID 21172676.

- Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H (May 2008). "Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (5): 408–16. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.048769. PMC 2647437. PMID 18545744.

- DeAntonio R, Yarzabal JP, Cruz JP, Schmidt JE, Kleijnen J (September 2016). "Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia and implications for vaccination of children living in developing and newly industrialized countries: A systematic literature review". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 12 (9): 2422–40. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1174356. PMC 5027706. PMID 27269963.

- Garenne M, Ronsmans C, Campbell H (1992). "The magnitude of mortality from acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years in developing countries". World Health Statistics Quarterly. 45 (2–3): 180–91. PMID 1462653.

- WHO (June 1999). "Pneumococcal vaccines. WHO position paper". Releve Epidemiologique Hebdomadaire. 74 (23): 177–83. PMID 10437429.

- Hoare Z, Lim WS (May 2006). "Pneumonia: update on diagnosis and management". BMJ. 332 (7549): 1077–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1077. PMC 1458569. PMID 16675815.

- Anevlavis S, Bouros D (February 2010). "Community acquired bacterial pneumonia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 11 (3): 361–74. doi:10.1517/14656560903508770. PMID 20085502.

- Kindermann D, Mutter R, Pines JM (May 2013). "Emergency Department Transfers to Acute Care Facilities, 2009". HCUP Statistical Brief #155. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C (September 2013). "Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #162. Rockville, MD.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Torio CM, Andrews RM (August 2013). "National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #160. Rockville, MD.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Lopez-Gonzalez L, Pickens GT, Washington R, Weiss AJ (October 2014). "Characteristics of Medicaid and Uninsured Hospitalizations, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #183. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Almirall J, Bolíbar I, Balanzó X, González CA (February 1999). "Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based case-control study" (PDF). The European Respiratory Journal. 13 (2): 349–55. doi:10.1183/09031936.99.13234999. PMID 10065680.