Dilation and curettage

Dilation (or dilatation) and curettage (D&C) refers to the dilation (widening/opening) of the cervix and surgical removal of part of the lining of the uterus and/or contents of the uterus by scraping and scooping (curettage). It is a therapeutic gynecological procedure as well as the most often used method of first trimester miscarriage or abortion.[1][2][3]

| Background | |

| Abortion type | Surgical |

| First use | Late 19th century |

| Gestation | 4-12 weeks |

| Usage | |

| WHO recommends only when manual vacuum aspiration is unavailable | |

| United States | 1.7% (2003) |

| Medical notes | |

| Undertaken under heavy sedation or general anesthesia. Risk of perforation. Day-case procedure | |

| Infobox references | |

D&C normally refers to a procedure involving a curette, also called sharp curettage.[2] However, some sources use the term D&C to refer more generally to any procedure that involves the processes of dilation and removal of uterine contents, which includes the more common suction curettage procedures of manual and electric vacuum aspiration.[4]

Procedure

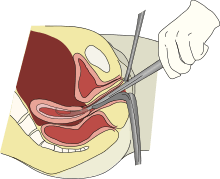

Depending on the anticipated duration and difficulty expected with the procedure, as well as the clinical indication and patient preferences, a D&C may be performed with local anesthesia, moderate sedation, deep sedation, or general anesthesia.[5] The first step in a D&C is to dilate the cervix. This can be done with Hegar dilators. After sufficient dilation, a curette, a metal rod with a handle on one end and a loop on the other, is then inserted into the uterus through the dilated cervix. The curette is used to gently scrape the lining of the uterus and remove the tissue in the uterus. If a suction curette is used, a plastic tubular curette will be introduced into the uterus and connected to suction to remove all tissue in the uterus. This tissue is examined for completeness (in the case of abortion or miscarriage treatment) or by pathology for abnormalities (in the case of treatment for abnormal bleeding).[2]

Clinical uses

D&Cs may be performed in pregnant and non-pregnant patients, for different clinical indications.

During pregnancy or postpartum

A D&C may be performed early in pregnancy to remove pregnancy tissue, either in the case of a non-viable pregnancy, such as a missed or incomplete miscarriage, or an undesired pregnancy, as in a surgical abortion. Medical management of miscarriage and medical abortion using drugs such as misoprostol and mifepristone are safe, non-invasive and potentially less expensive alternatives to D&C.

Because medication-based non-invasive methods of abortion now exist, the procedure has been declining as a method of abortion, although suction curettage is still the most common method used for termination of a first trimester pregnancy.[6][7] The World Health Organization recommends D&C with a sharp curette as a method of surgical abortion only when manual vacuum aspiration with a suction curette is unavailable.[8]

For patient who have recently given birth, a D&C may be indicated to remove retained placental tissue that does not pass spontaneously.[9]

Non-pregnant patients

D&Cs for non-pregnant patients are commonly performed for the diagnosis of gynecological conditions leading to abnormal uterine bleeding;[10] to remove the excess uterine lining in women who have conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (which cause a prolonged buildup of tissue with no natural period to remove it);[11] to remove tissue in the uterus that may be causing abnormal uterine bleeding, such as endometrial polyps or uterine fibroids,[3][2] or to diagnose the cause of post-menopausal bleeding.

Hysteroscopy is a valid alternative or addition to D&C for many surgical indications, from diagnosis of uterine pathology to the removal of fibroids and even retained products of conception. It allows direct visualization of the inside of the uterus and may allow targeted sampling and removal of tissue inside the uterus.[12]

Complications

The most common complications associated with D&C are infection, bleeding, or damage to nearby organs, including through uterine perforation. Aside from the surgery itself, complications related to anesthesia may also occur.

Infection is uncommon after D&C for a non-pregnant patient, and society practice guidelines do not recommend routine prophylactic antibiotics to patients.[13] However, for curettage of a pregnant patient, the risk of infection is higher, and patients should receive antibiotics that cover the bacteria commonly found in the vagina and gastrointestinal tract; doxycycline is a common recommendation, though azithromycin may also be used.[13]

Another risk of D&C is uterine perforation. The highest rate of uterine perforation appears to be in the setting of postpartum hemorrhage (5.1%) compared with a lower rate in diagnostic curettage in non-pregnant patients (0.3% in the premenopausal patient and 2.6% in the postmenopausal patient).[14] Perforation may cause excessive bleeding or damage to organs outside the uterus. If the provider is concerned about ongoing bleeding or the possibility of injury to organs outside the uterus, a laparoscopy may be done to verify that there has been no undiagnosed injury.

Another risk is intrauterine adhesions, or Asherman's syndrome. One study found that in women who had one or two sharp curettage procedures for miscarriage, 14-16% developed some adhesions.[15] Women who underwent three sharp curettage procedures for miscarriage had a 32% risk of developing adhesions.[15] The risk of Asherman's syndrome was found to be 30.9% in women who had D&C following a missed miscarriage,[16] and 25% in those who had a D&C 1–4 weeks postpartum.[17][18][19] Untreated Asherman's syndrome, especially if severe, also increases the risk of complications in future pregnancies, such as ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, and abnormal placentation (e.g.placenta previa and placenta accreta). According to recent case reports, use of vacuum aspiration can also lead to intrauterine adhesions.[20] A systematic review in 2013 came to the conclusion that recurrent miscarriage and D&C are the main risk factors for intrauterine adhesions.[21] However, that review also found no studies reporting a link between intrauterine adhesions and long-term reproductive outcome, and that similar pregnancy outcomes were reported subsequent to surgical management (including D&C), medical management or conservative management (that is, watchful waiting).[21]

References

- Pazol, Karen. "Ph.D". Center for Disease control. Center for Disease Control. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Dilation and sharp curettage (D&C) for abortion". Women's Health. WebMD. 2004-10-07. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- Hayden, Merrill (2006-02-22). "Dilation and curettage (D&C) for dysfunctional uterine bleeding". Healthwise. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2007-04-29.Nissl, Jan (2005-01-18). "Dilation and curettage (D&C) for bleeding during menopause". Healthwise. WebMD. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- "What Every Pregnant Woman Needs to Know About Pregnancy Loss and Neonatal Death". The Unofficial Guide to Having a Baby. WebMD. 2004-10-07. Archived from the original on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

- Allen, Rebecca H.; Singh, Rameet (2018-06-01). "Society of Family Planning clinical guidelines pain control in surgical abortion part 1 — local anesthesia and minimal sedation". Contraception. 97 (6): 471–477. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.014. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 29407363.

- "Minor surgical procedure common in O&G associated with increased risk of preterm delivery". EurekAlert!. European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- "Induced Abortion in the United States". Guttmacher Institute. September 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- World Health Organization, UNICEF, United Nations Population Fund (2017). Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. pp. P-71. ISBN 9789241565493.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Wolman I, Altman E, Fait G, Har-Toov J, Gull I, Amster R, Jaffa A (2009). "Evacuating retained products of conception in the setting of an ultrasound unit". Fertil. Steril. 91 (4 Suppl): 1586–88. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.032. PMID 19064261.

- Anastasiadis PG, Koutlaki NG, Skaphida PG, Galazios GC, Tsikouras PN, Liberis VA (2000). "Endometrial polyps: prevalence, detection, and malignant potential in women with abnormal uterine bleeding". Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 21 (2): 180–183. PMID 10843481.

- "Dilation and Curettage (D&C)". www.phyllisgeemd.com. Practice Builders & Health Central Women's Care, PA. 2016. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- "Hysteroscopy". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "Prevention of Infection After Gynecologic Procedures: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 195". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 131 (6): e172–e189. June 2018. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002670. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 29794678.

- Hefler, Lukas; Lemach, Andrea; Seebacher, Veronika; Polterauer, Stephan; Tempfer, Clemens; Reinthaller, Alexander (June 2009). "The Intraoperative Complication Rate of Nonobstetric Dilation and Curettage". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 113 (6): 1268–1271. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a66f91. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 19461421.

- Friedler S, Margalioth EJ, Kafka I, Yaffe H (1993). "Incidence of post-abortion intra-uterine adhesions evaluated by hysteroscopy--a prospective study". Hum. Reprod. 8 (3): 442–4. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138068. PMID 8473464.

- Schenker JG, Margalioth EJ (1982). "Intra-uterine adhesions: an updated appraisal". Fertility and Sterility. 37 (5): 593–610. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)46268-0. PMID 6281085.

- Kodaman PH, Arici A (2007). "Intrauterine adhesions and fertility outcome:how to optimize success?". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 19 (3): 207–214. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32814a6473. PMID 17495635.

- Rochet Y, Dargent D, Bremond A, Priou G, Rudigoz RC (1979). "The obstetrical outcome of women with surgically treated uterine synechiae (in French)". J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 8 (8): 723–726. PMID 553931.

- Buttram VC, Turati G (1977). "Uterine synechiae: variations in severity and some conditions which may be conducive to severe adhesions". Int. J. Fertil. 22 (2): 98–103. PMID 20418.

- Dalton VK, Saunders NA, Harris LH, Williams JA, Lebovic DI (2006). "Intrauterine adhesions after manual vacuum aspiration for early pregnancy failure". Fertil. Steril. 85 (6): 1823.e1–3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.065. PMID 16674955.

- Hooker AB, Lemmers M, Thurkow AL, Heymans MW, Opmeer BC, Brölmann HA, Mol BW, Huirne JA (2013). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of intrauterine adhesions after miscarriage: Prevalence, risk factors and long-term reproductive outcome" (PDF). Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 262–78. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt045. PMID 24082042.