Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia is abnormally elevated levels of any or all lipids or lipoproteins in the blood.[2]

| Hyperlipidemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hyperlipoproteinemia, hyperlipidaemia[1] |

| |

| A 4-ml sample of hyperlipidemic blood in a vacutainer with EDTA. Left to settle for four hours without centrifugation, the lipids separated into the top fraction. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Lipids (water-insoluble molecules) are transported in a protein capsule.[3] The size of that capsule, or lipoprotein, determines its density.[3] The lipoprotein density and type of apolipoproteins it contains determines the fate of the particle and its influence on metabolism.

Hyperlipidemias are divided into primary and secondary subtypes. Primary hyperlipidemia is usually due to genetic causes (such as a mutation in a receptor protein), while secondary hyperlipidemia arises due to other underlying causes such as diabetes. Lipid and lipoprotein abnormalities are common in the general population and are regarded as modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease due to their influence on atherosclerosis.[4] In addition, some forms may predispose to acute pancreatitis.

Relation to cardiovascular disease

Hyperlipidemia predisposes a person to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is the accumulation of lipids, cholesterol, calcium, fibrous plaques within the artery walls of the heart.[5] This accumulation narrows the blood vessel and reduce blood flow and oxygen to muscles of the heart.[5] Complete blockage of the artery causes infarction of the myocardial cells, also known as heart attack.[6]

Classification

Hyperlipidemias may basically be classified as either familial (also called primary[7]) caused by specific genetic abnormalities, or acquired (also called secondary)[7] when resulting from another underlying disorder that leads to alterations in plasma lipid and lipoprotein metabolism.[7] Also, hyperlipidemia may be idiopathic, that is, without a known cause.

Hyperlipidemias are also classified according to which types of lipids are elevated, that is hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia or both in combined hyperlipidemia. Elevated levels of Lipoprotein(a) may also be classified as a form of hyperlipidemia.

Familial (primary)

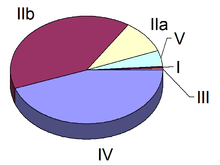

Familial hyperlipidemias are classified according to the Fredrickson classification, which is based on the pattern of lipoproteins on electrophoresis or ultracentrifugation.[8] It was later adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO). It does not directly account for HDL, and it does not distinguish among the different genes that may be partially responsible for some of these conditions.

| Hyperlipo- proteinemia |

OMIM | Synonyms | Defect | Increased lipoprotein | Main symptoms | Treatment | Serum appearance | Estimated prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | a | 238600 | Buerger-Gruetz syndrome or familial hyperchylomicronemia | Decreased lipoprotein lipase (LPL) | Chylomicrons | Acute pancreatitis, lipemia retinalis, eruptive skin xanthomas, hepatosplenomegaly | Diet control | Creamy top layer | One in 1,000,000[9] |

| b | 207750 | Familial apoprotein CII deficiency | Altered ApoC2 | ||||||

| c | 118830 | LPL inhibitor in blood | |||||||

| Type II | a | 143890 | Familial hypercholesterolemia | LDL receptor deficiency | LDL | Xanthelasma, arcus senilis, tendon xanthomas | Bile acid sequestrants, statins, niacin | Clear | One in 500 for heterozygotes |

| b | 144250 | Familial combined hyperlipidemia | Decreased LDL receptor and increased ApoB | LDL and VLDL | Statins, niacin, fibrate | Turbid | One in 100 | ||

| Type III | 107741 | Familial dysbetalipoproteinemia | Defect in Apo E 2 synthesis | IDL | Tuboeruptive xanthomas and palmar xanthomas | Fibrate, statins | Turbid | One in 10,000[10] | |

| Type IV | 144600 | Familial hypertriglyceridemia | Increased VLDL production and decreased elimination | VLDL | Can cause pancreatitis at high triglyceride levels | Fibrate, niacin, statins | Turbid | One in 100 | |

| Type V | 144650 | Increased VLDL production and decreased LPL | VLDL and chylomicrons | Niacin, fibrate | Creamy top layer and turbid bottom | ||||

Type I

Type I hyperlipoproteinemia exists in several forms:

- Lipoprotein lipase deficiency (type Ia), due to a deficiency of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) or altered apolipoprotein C2, resulting in elevated chylomicrons, the particles that transfer fatty acids from the digestive tract to the liver

- Familial apoprotein CII deficiency (type Ib),[12][13] a condition caused by a lack of lipoprotein lipase activator.[14]:533

- Chylomicronemia due to circulating inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase (type Ic)[15]

Type I hyperlipoproteinemia usually presents in childhood with eruptive xanthomata and abdominal colic. Complications include retinal vein occlusion, acute pancreatitis, steatosis, and organomegaly, and lipemia retinalis.

Type II

Hyperlipoproteinemia type II, by far the most common form, is further classified into types IIa and IIb, depending mainly on whether elevation in the triglyceride level occurs in addition to LDL cholesterol.

Type IIa

This may be sporadic (due to dietary factors), polygenic, or truly familial as a result of a mutation either in the LDL receptor gene on chromosome 19 (0.2% of the population) or the ApoB gene (0.2%). The familial form is characterized by tendon xanthoma, xanthelasma, and premature cardiovascular disease. The incidence of this disease is about one in 500 for heterozygotes, and one in 1,000,000 for homozygotes.

HLPIIa is a rare genetic disorder characterized by increased levels of LDL cholesterol in the blood due to the lack of uptake (no Apo B receptors) of LDL particles. This pathology, however, is the second-most common disorder of the various hyperlipoproteinemias, with individuals with a heterozygotic predisposition of one in every 500 and individuals with homozygotic predisposition of one in every million. These individuals may present with a unique set of physical characteristics such as xanthelasmas (yellow deposits of fat underneath the skin often presenting in the nasal portion of the eye), tendon and tuberous xanthomas, arcus juvenilis (the graying of the eye often characterized in older individuals), arterial bruits, claudication, and of course atherosclerosis. Laboratory findings for these individuals are significant for total serum cholesterol levels two to three times greater than normal, as well as increased LDL cholesterol, but their triglycerides and VLDL values fall in the normal ranges.

To manage persons with HLPIIa, drastic measures may need to be taken, especially if their HDL cholesterol levels are less than 30 mg/dL and their LDL levels are greater than 160 mg/dL. A proper diet for these individuals requires a decrease in total fat to less than 30% of total calories with a ratio of monounsaturated:polyunsaturated:saturated fat of 1:1:1. Cholesterol should be reduced to less than 300 mg/day, thus the avoidance of animal products and to increase fiber intake to more than 20 g/day with 6g of soluble fiber/day. Exercise should be promoted, as it can increase HDL. The overall prognosis for these individuals is in the worst-case scenario if uncontrolled and untreated individuals may die before the age of 20, but if one seeks a prudent diet with correct medical intervention, the individual may see an increased incidence of xanthomas with each decade, and Achilles tendinitis and accelerated atherosclerosis will occur.

Type IIb

The high VLDL levels are due to overproduction of substrates, including triglycerides, acetyl-CoA, and an increase in B-100 synthesis. They may also be caused by the decreased clearance of LDL. Prevalence in the population is 10%.

- Familial combined hyperlipoproteinemia (FCH)

- Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency, often called (Cholesteryl ester storage disease)

- Secondary combined hyperlipoproteinemia (usually in the context of metabolic syndrome, for which it is a diagnostic criterion)

Type III

This form is due to high chylomicrons and IDL (intermediate density lipoprotein). Also known as broad beta disease or dysbetalipoproteinemia, the most common cause for this form is the presence of ApoE E2/E2 genotype. It is due to cholesterol-rich VLDL (β-VLDL). Its prevalence has been estimated to be approximately 1 in 10,000.[10]

It is associated with hypercholesterolemia (typically 8–12 mmol/L), hypertriglyceridemia (typically 5–20 mmol/L), a normal ApoB concentration, and two types of skin signs (palmar xanthomata or orange discoloration of skin creases, and tuberoeruptive xanthomata on the elbows and knees). It is characterized by the early onset of cardiovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease. Remnant hyperlipidemia occurs as a result of abnormal function of the ApoE receptor, which is normally required for clearance of chylomicron remnants and IDL from the circulation. The receptor defect causes levels of chylomicron remnants and IDL to be higher than normal in the blood stream. The receptor defect is an autosomal recessive mutation or polymorphism.

Type IV

Familial hypertriglyceridemia is an autosomal dominant condition occurring in approximately 1% of the population.[16]

This form is due to high triglyceride level. Other lipoprotein levels are normal or increased a little.

Treatment include diet control, fibrates and niacins. Statins are not better than fibrates when lowering triglyceride levels.

Type V

Hyperlipoproteinemia type V, also known as mixed hyperlipoproteinemia familial or mixed hyperlipidemia,[17] is very similar to type I, but with high VLDL in addition to chylomicrons.

It is also associated with glucose intolerance and hyperuricemia.

In medicine, combined hyperlipidemia (or -aemia) (also known as "multiple-type hyperlipoproteinemia") is a commonly occurring form of hypercholesterolemia (elevated cholesterol levels) characterized by increased LDL and triglyceride concentrations, often accompanied by decreased HDL.[18] On lipoprotein electrophoresis (a test now rarely performed) it shows as a hyperlipoproteinemia type IIB. It is the most common inherited lipid disorder, occurring in about one in 200 persons. In fact, almost one in five individuals who develop coronary heart disease before the age of 60 has this disorder. The elevated triglyceride levels (>5 mmol/l) are generally due to an increase in very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), a class of lipoprotein prone to cause atherosclerosis.

Types

- Familial combined hyperlipidemia (FCH) is the familial occurrence of this disorder, probably caused by decreased LDL receptor and increased ApoB.

- FCH is extremely common in people who suffer from other diseases from the metabolic syndrome ("syndrome X", incorporating diabetes mellitus type II, hypertension, central obesity and CH). Excessive free fatty acid production by various tissues leads to increased VLDL synthesis by the liver. Initially, most VLDL is converted into LDL until this mechanism is saturated, after which VLDL levels elevate.

Both conditions are treated with fibrate drugs, which act on the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), specifically PPARα, to decrease free fatty acid production. Statin drugs, especially the synthetic statins (atorvastatin and rosuvastatin) can decrease LDL levels by increasing hepatic reuptake of LDL due to increased LDL-receptor expression.

Unclassified familial forms

These unclassified forms are extremely rare:

- Hyperalphalipoproteinemia

- Polygenic hypercholesterolemia

Acquired (secondary)

Acquired hyperlipidemias (also called secondary dyslipoproteinemias) often mimic primary forms of hyperlipidemia and can have similar consequences.[7] They may result in increased risk of premature atherosclerosis or, when associated with marked hypertriglyceridemia, may lead to pancreatitis and other complications of the chylomicronemia syndrome.[7] The most common causes of acquired hyperlipidemia are:

- Diabetes mellitus[7]

- Use of drugs such as thiazide diuretics,[7] beta blockers,[7] and estrogens[7]

Other conditions leading to acquired hyperlipidemia include:

- Hypothyroidism[7]

- Kidney failure[7]

- Nephrotic syndrome[7]

- Alcohol consumption[7]

- Some rare endocrine disorders[7] and metabolic disorders[7]

Treatment of the underlying condition, when possible, or discontinuation of the offending drugs usually leads to an improvement in the hyperlipidemia.

Another acquired cause of hyperlipidemia, although not always included in this category, is postprandial hyperlipidemia, a normal increase following ingestion of food.[18][19]

Screening

Serum level of Low Density Lipoproteins (LDL) cholesterol, High Density Lipoproteins (HDL) Cholesterol, and triglycerides are commonly tested in primary care setting using a lipid panel. Quantitative levels of lipoproteins and triglycerides contribute toward cardiovascular disease risk stratification via models/calculators such as Framingham Risk Score, ACC/AHA Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Estimator, and/or Reynolds Risk Scores. These models/calculators may also take into account of family history (heart disease and/or high blood cholesterol), age, gender, Body-Mass-Index, medical history (diabetes, high cholesterol, heart disease), high sensitivity CRP levels, coronary artery calcium score, and ankle-brachial index.[20] The cardiovascular stratification further determines what medical intervention may be necessary to decrease the risk of future cardiovascular disease.

Total cholesterol

The combined quantity of LDL and HDL. A total cholesterol of higher than 240mg/dL is abnormal, but medical intervention is determined by the breakdown of LDL and HDL levels.[21]

LDL cholesterol

LDL,commonly known as "bad cholesterol", is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[22][23] It is also associated with diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and atherosclerosis. In a fasting lipid panel, a LDL greater than 160 mg/dL is abnormal.[20][21]

HDL Cholesterol

HDL, also known as "good cholesterol", is associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular disease.[23] It can be affected by acquired or genetic factors, including tobacco use, obesity, inactivity, hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, high carbohydrate diet, medication side effects (beta-blockers, androgenic steroids, corticosteroids, progestogens, thiazide diuretics, retinoic acid derivatives, oral estrogens, etc.) and genetic abnormalities (mutations ApoA-I, LCAT, ABC1).[20] Low level is defined as less than 40 mg/dL.[21][24]

Triglycerides

Triglyceride level is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and/or metabolic syndrome.[20] Food intake prior to testing may cause elevated levels, up to 20%. Normal level is defined as less than 150 mg/dL. Borderline high is defined as 150 to 199 mg/dL. High level is between 200 to 499 mg/dL. Greater than 500mg/dL is defined as very high, and is associated with pancreatitis and requires medical treatment.[25]

Screening age

Health organizations does not have a consensus on the age to begin screening for hyperlipidemia.[20] USPSTF recommends men older than 35 and women older than 45 to be screened.[26][27] NCE-ATP III recommends all adults older than 20 to be screened as it may lead potential lifestyle modification that can reduce risks of other diseases.[28] However, screening should be done for those with known CHD or risk-equivalent conditions (e.g. Acute Coronary Syndrome, history of heart attacks, Stable or Unstable angina, Transient ischemic attacks, Peripheral arterial disease of atherosclerotic origins, coronary or other arterial revascularization).[20]

Management

Management of hyperlipidemia includes maintenance of a normal body weight, increased physical activity, and decreased consumption of refined carbohydrates and simple sugars.[29] Prescription drugs may be used to treat some people having significant risk factors,[29] such as cardiovascular disease, LDL cholesterol greater than 190 mg/dl or diabetes. Common medication therapy is a statin.[29][30]

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors

Competitive inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase, such as lovastatin, atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, rosuvastatin, and pitavastatin, inhibit the synthesis of mevalonate, a precursor molecule to cholesterol.[31] This medication class is especially effective at decreasing elevated LDL cholesterol.[31] Major side effects include elevated transaminases and myopathy.[31]

Fibric acid derivatives

Fibric acid derivatives, such as gemfibrozil and fenofibrate, function by increasing the lipolysis in adipose tissue via activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α.[31] They decrease VLDL - very low density lipoprotein - and LDL in some people.[31] Major side effects include rashes, GI upset, myopathy, or increased transaminases.[31]

Niacin

Niacin, or vitamin B3 has a mechanism of action that is poorly understood, however it has been shown to decrease LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, and increase HDL cholesterol.[31] The most common side effect is flushing secondary to skin vasodilation.[31] This effect is mediated by prostaglandins and can be decreased by taking concurrent aspirin.[31]

Bile acid binding resins

Bile acid binding resins, such as colestipol, cholestyramine, and colesevelam, function by binding bile acids, increasing their excretion.[31] They are useful for decreasing LDL cholesterol.[31] The most common side effects include bloating and diarrhea.[31]

Sterol absorption inhibitors

Inhibitors of intestinal sterol absorption, such as ezetimibe, function by decreasing the absorption of cholesterol in the GI tract by targeting NPC1L1, a transport protein in the gastrointestinal wall.[31] This results in decreased LDL cholesterol.[31]

See also

References

- Youngson RM (2005). "Hyperlipidaemia". Collins Dictionary of Medicine.

- "Hyperlipidemia". The Free Dictionary. citing: Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers. Saunders. 2007. and The American Heritage Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2007.

- Hall JE (2016). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology. Elsevier. ISBN 9781455770052. OCLC 932195756.

- Lilly L. Pathophysiology of heart disease : a collaborative project of medical students and faculty. ISBN 1496308697. OCLC 1052840871.

- Linton MF, Yancey PG, Davies SS, Jerome WG, Linton EF, Song WL, Doran AC, Vickers KC (2000). Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G (eds.). "The Role of Lipids and Lipoproteins in Atherosclerosis". Endotext. MDText.com, Inc. PMID 26844337. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- Bergheanu SC, Bodde MC, Jukema JW (April 2017). "Pathophysiology and treatment of atherosclerosis : Current view and future perspective on lipoprotein modification treatment". Netherlands Heart Journal. 25 (4): 231–242. doi:10.1007/s12471-017-0959-2. PMC 5355390. PMID 28194698.

- Chait A, Brunzell JD (June 1990). "Acquired hyperlipidemia (secondary dyslipoproteinemias)". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 19 (2): 259–78. doi:10.1016/S0889-8529(18)30324-4. PMID 2192873.

- Fredrickson DS, Lees RS (March 1965). "A system for phenotyping hyperlipoproteinemia" (PDF). Circulation. 31 (3): 321–7. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.31.3.321. PMID 14262568.

- "Hyperlipoproteinemia, Type I". Centre for Arab Genomic Studies. 6 March 2007. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012.

About 1:1,000,000 people are affected with Hyperlipoproteinemia type I worldwide with a higher prevalence in some regions of Canada.

- Fung M, Hill J, Cook D, Frohlich J (June 2011). "Case series of type III hyperlipoproteinemia in children". BMJ Case Reports. 2011: bcr0220113895. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3895. PMC 3116222. PMID 22691586.

- "New Product Bulletin on Crestor® (rosuvastatin)". American Pharmacists Association. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Apolipoprotein C-II Deficency -207750

- Yamamura T, Sudo H, Ishikawa K, Yamamoto A (September 1979). "Familial type I hyperlipoproteinemia caused by apolipoprotein C-II deficiency". Atherosclerosis. 34 (1): 53–65. doi:10.1016/0021-9150(79)90106-0. hdl:11094/32883. PMID 227429.

- James WD, Berger TG, et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Chylomicronemia, Familial, Due to Circulating Inhibitor of Lipoprotein Lipase -118830

- Boman H, Hazzard WR, AlbersJJ, et ah Frequency of monogenic forms of hyperlipidemia in a normal population. AmJ ttum Genet 27:19A,1975.

- "Medical Definition Search For 'Type 5 Hyperlipidemia". medilexicon. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "Hyperlipidemia". The Free Dictionary. Citing: Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary (3rd ed.). Elsevier. 2007.

- Ansar S, Koska J, Reaven PD (July 2011). "Postprandial hyperlipidemia, endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular risk: focus on incretins". Cardiovascular Diabetology. 10: 61. doi:10.1186/1475-2840-10-61. PMC 3184260. PMID 21736746.

- Kopin L, Lowenstein C (December 2017). "Dyslipidemia". Annals of Internal Medicine. 167 (11): ITC81–ITC96. doi:10.7326/AITC201712050. PMID 29204622.

- "ATP III Guidelines At-A-Glance Quick Desk Reference" (PDF). National Heart, Lungs, and Blood Institute. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Pirahanchi Y, Huecker MR (2019), "Biochemistry, LDL Cholesterol", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30137845, retrieved 2019-11-06

- CDC (2017-10-31). "LDL and HDL Cholesterol: "Bad" and "Good" Cholesterol". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- Information, National Center for Biotechnology (2017-09-07). High cholesterol: Overview. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG).

- Pejic RN, Lee DT (2006-05-01). "Hypertriglyceridemia". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 19 (3): 310–6. doi:10.3122/jabfm.19.3.310. PMID 16672684.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW, García FA, et al. (August 2016). "Screening for Lipid Disorders in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 316 (6): 625–33. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9852. PMID 27532917.

- "Final Update Summary: Lipid Disorders in Adults (Cholesterol, Dyslipidemia): Screening". US Preventive Services Task Force. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- Grundy SM. "Then and Now: ATP III vs. IV". American College of Cardiology. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- Michos ED, McEvoy JW, Blumenthal RS (October 2019). Jarcho JA (ed.). "Lipid Management for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (16): 1557–1567. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1806939. PMID 31618541.

- Harrison TR (1951). "Principles of Internal Medicine". Southern Medical Journal. 44 (1): 79. doi:10.1097/00007611-195101000-00027. ISSN 0038-4348.

- Katzung BG (2017-11-30). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology; 14th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education / Medical. ISBN 9781259641152. OCLC 1048625746.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |