Ezetimibe

Ezetimibe is a medication used to treat high blood cholesterol and certain other lipid abnormalities.[1] Generally it is used together with dietary changes and a statin.[2] Alone, it is less preferred than a statin.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1] It is also available in the combination ezetimibe/simvastatin.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ɛˈzɛtɪmɪb, -maɪb/ |

| Trade names | Zetia, Ezetrol, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603015 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| Drug class | Cholesterol absorption inhibitor |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 35% to 65% |

| Protein binding | >90% |

| Metabolism | Intestinal wall, liver |

| Elimination half-life | 19 h to 30 h |

| Excretion | Renal 11%, faecal 78% |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.207.996 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

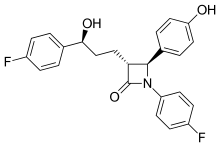

| Formula | C24H21F2NO3 |

| Molar mass | 409.4 g·mol−1 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 164 to 166 °C (327 to 331 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include upper respiratory tract infections, joint pain, diarrhea, and tiredness.[1] Serious side effects may include anaphylaxis, liver problems, depression, and muscle breakdown.[1][2] Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[3] Ezetimibe works by decreasing cholesterol absorption in the intestines.[2]

Ezetimibe was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[2] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £26.21 as of 2019.[2] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$5.85.[5] In 2016 it was the 144th most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 4 million prescriptions.[6]

Medical uses

A review found that ezetimibe used as sole treatment slightly lowered plasma levels of lipoprotein(a), but the effect was not large enough to be important.[7] A review found that adding ezetimibe to statin treatment of high blood cholesterol had no effect on overall mortality or cardiovascular mortality, although it significantly reduced the risk of MI and stroke.[8] A 2015 trial found that adding ezetimibe to simvastatin had no effect on overall mortality but did lower the risk of heart attack or stroke in people with prior heart attack.[9][10] Several treatment guidelines recommend adding ezetimibe in select high risk persons in whom LDL goals cannot be achieved by maximally tolerated statin alone.[11][12][13][14][15]

Ezetimibe is indicated in the United States as an add-on to dietary measures to reduce levels of certain lipids in people with:[16]

- Primary hyperlipidemia, alone or with a statin

- Mixed hyperlipidemia, in combination with fenofibrate

- Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, in combination with specific statins

- Homozygous sitosterolemia

Ezetimibe improves the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease activity score but the available evidence indicates it does not improve outcomes of hepatic steatosis.[17]

Contraindications

The two contraindications to taking ezetimibe are a previous allergic reaction to it, including symptoms of rash, angioedema, and anaphylaxis, and severe liver disease, especially when taken with a statin.[18]

Ezetimibe may have significant medication interactions with ciclosporin and with fibrates other than fenofibrate.[16]

Adverse effects

Common adverse drug reactions (≥1% of patients) associated with ezetimibe therapy include headache and/or diarrhea (steatorrhea). Infrequent adverse effects (0.1–1% of patients) include myalgia and/or raised liver function test (ALT/AST) results. Rarely (<0.1% of patients), hypersensitivity reactions (rash, angioedema) or myopathy may occur.[16] Cases of muscle problems (myalgia and rhabdomyolysis) have been reported and are included as warnings on the label for ezetimibe.[16]

Overdose

The incidence of overdose with ezetimibe is rare; subsequently, few data exist on the effects of overdose. However, an acute overdose of ezetimibe is expected to produce an exaggeration of its usual effects, leading to loose stools, abdominal pain, and fatigue.[19]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Ezetimibe inhibits the absorption of cholesterol from the small intestine and decreases the amount of cholesterol normally available to liver cells, leading them to absorb more from circulation, thus lowering levels of circulating cholesterol. It blocks the critical mediator of cholesterol absorption, the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 protein on the gastrointestinal tract epithelial cells, as well as in hepatocytes; it blocks aminopeptidase N and interrupts a caveolin 1–annexin A2 complex involved in trafficking cholesterol.[9]

Pharmacokinetics

Within 4–12 hours of the oral administration of a 10-mg dose to fasting adults, the attained mean ezetimibe peak plasma concentration (Cmax) was 3.4–5.5 ng/ml. Following oral administration, ezetimibe is absorbed and extensively conjugated to a phenolic glucuronide (active metabolite). Mean Cmax (45–71 ng/ml) of ezetimibe-glucuronide is attained within 1–2 hours. The concomitant administration of food (high-fat vs. nonfat meals) has no effect on the extent of absorption of ezetimibe. However, coadministration with a high-fat meal increases its Cmax by 38%. The absolute bioavailability cannot be determined, since ezetimibe is insoluble in aqueous media suitable for injection. Ezetimibe and its active metabolites are highly bound to human plasma proteins (90%).[16]

Ezetimibe is primarily metabolized in the liver and the small intestine via glucuronide conjugation with subsequent renal and biliary excretion.[20] Both the parent compound and its active metabolite are eliminated from plasma with a half-life around 22 hours, allowing for once-daily dosing. Ezetimibe lacks significant inhibitor or inducer effects on cytochrome P450 isoenzymes, which explains its limited number of drug interactions. No dose adjustment is needed in patients with chronic kidney disease or mild hepatic dysfunction (Child-Pugh score 5–6). Due to insufficient data, the manufacturer does not recommend ezetimibe for patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score 7–15). In patients with mild, moderate, or severe hepatic impairment, the mean AUC values for total ezetimibe are increased about 1.7-fold, 3-to-4-fold, and 5-to-6-fold, respectively, compared to healthy subjects.[16]

Cost

In the United States as of 2019 it costs about 0.21 USD per dose.[5] In 2015, it cost between US$4.84 and 7.88.[21]

See also

References

- "Ezetimibe Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 196. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "Ezetimibe (Zetia) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Ezetimibe Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Awad K, Mikhailidis DP, Katsiki N, Muntner P, Banach M (March 2018). "Effect of Ezetimibe Monotherapy on Plasma Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations in Patients with Primary Hypercholesterolemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Drugs. 78 (4): 453–462. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-0870-1. PMID 29396832.

- Savarese G, De Ferrari GM, Rosano GM, Perrone-Filardi P (December 2015). "Safety and efficacy of ezetimibe: A meta-analysis". Int. J. Cardiol. 201: 247–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.103. PMID 26301648.

- Phan BA, Dayspring TD, Toth PP (2012). "Ezetimibe therapy: mechanism of action and clinical update". Vasc Health Risk Manag. 8: 415–27. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S33664. PMC 3402055. PMID 22910633.

- Cannon, Christopher P. (June 18, 2015). "Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes". New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (25): 2387–2397. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. PMID 26039521.

- Alenghat, Francis J.; Davis, Andrew M. (2019). "Management of Blood Cholesterol". JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0015. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 30715135.

- Catapano AL, Reiner Z, De Backer G, et al. (July 2011). "ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS)". Atherosclerosis. 217 (1): 3–46. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.06.011. PMID 21882396.

- Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, et al. (2013). "Executive summary of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guidelines for the diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Japan -2012 version". J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 20 (6): 517–23. doi:10.5551/jat.15792. PMID 23665881.

- "Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". Archived from the original on 2014-11-19.

- Expert Dyslipidemia Panel of the International Atherosclerosis Society Panel members (2014). "An International Atherosclerosis Society Position Paper: global recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia--full report". J Clin Lipidol. 8 (1): 29–60. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2013.12.005. PMID 24528685.

- Zetia label, Rev 23. Revised: January 2012

- Lee HY, Jun DW, Kim HJ, Oh H, Saeed WK, Ahn H, Cheung RC, Nguyen MH (March 2018). "Ezetimibe decreased nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score but not hepatic steatosis". Korean J. Intern. Med. doi:10.3904/kjim.2017.194. PMC 6406097. PMID 29551054.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Page last updated: 27 October 2014 Medline Plus: Ezetimibe

- "Ezetimibe - National Library of Medicine HSDB Database". toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- SJS Basha; SA Naveed; NK Tiwari; D Shashikumar; S Muzeeb; TR Kumar; NV Kumar; NP Rao; N Srinivas; M Ramesh; NR Srinivas (2007). "Mechanism of Drug-Drug Interactions Between Warfarin and Statins". Journal of Chromatography B. 853 (1): 88–96. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.02.053. PMID 17442643.

- Langreth, Robert (June 29, 2016). "Decoding Big Pharma's Secret Drug Pricing Practices". Bloomberg. Retrieved 15 July 2016.