Blood

On this Page

Some parasites can be bloodborne. This means:

- the parasite can be found in the bloodstream of infected people; and

- the parasite might be spread to other people through exposure to an infected person's blood (for example, by blood transfusion or by sharing needles or syringes contaminated with blood).

Examples of parasitic diseases that can be bloodborne include African trypanosomiasis, babesiosis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, malaria, and toxoplasmosis. In nature, many bloodborne parasites are spread by insects (vectors), so they are also referred to as vector-borne diseases. Toxoplasma gondii is not transmitted by an insect (vector).

In the United States, the risk for vector-borne transmission is very low for these parasites except for some Babesia species.

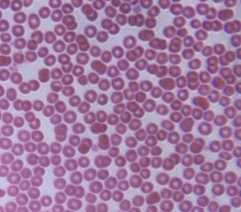

Microscopic red blood cells.

Blood Transfusions

Many factors affect whether parasites that can be found in the bloodstream might be spread by blood transfusion. Examples of some of the factors include:

- how much of the parasite’s life cycle is spent in the blood;

- how many parasites might be found in the blood (in other words, the concentration or level of the parasite);

- how long the parasite stays in the body, in treated and untreated people; and

- how the parasite affects people. For example, if infected people feel sick, they might not want to donate blood or they might be deferred (turned away).

Some parasites spend most or all of their life cycle in the bloodstream, such as Babesia and Plasmodium species. Parasites, such as Trypanosoma cruzi, might be found in the blood early in an infection (the acute phase) and then at much lower levels later (the chronic phase of infection). Other parasites only migrate (travel) through the blood to get to another part of the body.

There may be cases of transfusion-transmitted parasites that go undetected and unreported, but the risk for infection is very low compared with the number of blood transfusions. In the United States since 1980, there have been published reports of cases of transfusion-associated babesiosis (>150), malaria (~50), and Chagas disease (~5). Since 1965, there have been published reports of transfusion-associated toxoplasmosis (~4).

More on: Tools for investigating potential cases of transfusion-associated parasitic diseases

Blood Donor Screening

Potential blood donors are asked if they have had babesiosis or Chagas disease. If the answer is "yes," the person is deferred from donating blood.

Potential blood donors are also asked about their recent international travel. People who traveled to an are where malaria transmission occurs are deferred from donating blood for 1 year after their return to the United States. Former residents of areas where malaria transmission occurs will be deferred for 3 years. People diagnosed with malaria cannot donate blood for 3 years after treatment, during which time they must have remained free of symptoms of malaria.

Donated blood is tested for a number of infectious agents. Currently, most of the U.S. blood supply is screened for Trypanosoma cruzi (the parasite that causes Chagas disease). If the results are positive, the blood center will try to notify the donor. People who test positive should consult a health care provider. Health care providers may contact CDC for confirmatory testing and management information, including treatment.

More on: Chagas & Blood Donor Screening

- Page last reviewed: May 18, 2016

- Page last updated: May 18, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir