Disaster Epi: HSB staff's field experience boosts national data reporting

Cross-CDC efforts to innovate, expedite death toll surveillance

You often hear about the importance of electronic medical records and electronic health records, but what about electronic death records? In a disaster, prompt and accurate recording of death certificates are critical for effective post-disaster surveillance. Until recent CDC efforts, however, timely and accurate vital records lagged far behind what public health and communities in distress need.

No one knows this issue better than Commander Rebecca Noe, an epidemiologist specializing in environmental disaster response. In her 6-year career with the National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH), Noe has spent many days on the front lines of field surveillance gathering critical information following deadly disasters. (See more about Noe’s professional and personal interests in the environment and her award as “Responder of the Year” for 2015 from the U.S. Commissioned Corps following this story.)

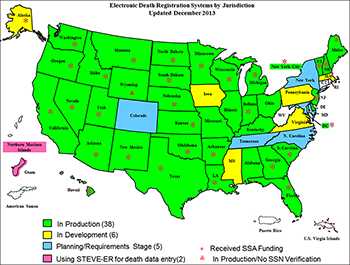

Early on, the big questions in Noe’s mind became: How are disaster deaths being tracked in the U.S. and can we leverage the state-based Electronic Death Registration Systems (EDRS) for timely and better mortality data during and soon after a disaster?

“This kind of work supports community resilience after a disaster. FEMA provides funeral benefits to families but require families’ to obtain, deliver, and produce a paper copy of the death certificate to receive these funds. More efficient electronic data sharing via state-based EDRS during a disaster could alleviate this burdened to these grieving families.

She actually discovered a more basic issue. “A death certificate might indicate a person died from a traumatic head injury, but there would be no mention of a tornado,” Noe said, recalling the epidemiology investigation after the spate of tornadoes struck the Southeast in 2011. Similarly, she said, after Hurricane Ike wreaked havoc through Texas and nearby states in 2008, out of 75 deaths captured in active surveillance following the hurricane, only five percent could be identified as related to the hurricane, in a key word search (e.g., Ike, storm) of the vital statistics data.

Improved mortality data can benefit communities and families after disasters

While accurate and complete mortality data are critical for public health disaster response and epidemiologic research, it also has many personal implications for individual families affected by a disaster, Noe noted.

“This kind of work supports community resilience after a disaster, “she said. “More efficient electronic data-sharing can enable individuals and families to receive Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funeral benefits for their lost loved ones in a timely manner, and not be burdened with often complicated administrative hurdles.”

To tackle this challenge, Noe is working with several partners to develop guidance for Medical Examiners and Coroners on properly completing death certificates of disaster deaths. She also organized a national webinar to encourage a dialogue on leveraging the state-based Electronic Death Registration Systems (EDRS) for “near-real time” mortality data during a disaster. Mortality data are one of several types of information gathered, housed, and transmitted via the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) at National center for Health Statistics.

Based on her field experiences, Noe recognized that the epi challenge came down to strengthening surveillance capacities for tracking disaster-related deaths by making the following changes:

- Encouraging states to examine the capabilities of their existing state-based EDRS;

- Developing consensus case definitions and standards for certifying disaster related deaths; and

- Developing guidelines and best practices for consistent cause of death reporting using electronic death registration systems (EDRS).

Recent experiences informed next steps

What are NVSS? NCHS?

The National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) is an inter-governmental system of sharing data on the vital statistics of the population of the United States. It involves coordination between the different state health departments of the US states and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), a Center of CDC. NCHS’s mission is to gather and report statistics based on official records of live births, deaths, fetal deaths, marriages, divorces, and annulments. States and territories have the responsibility to record these events and transmit the information via NVSS to NCHS. For more information, see http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss.htm.

Over the last several years, Noe has reached out to states where recent disasters have occurred to gather “success stories” on how EDRS systems improvements can make a clear difference. For example:

- In 2014 the WA state Oso mudslide, the medical examiner office used EDRS to register deaths with the state. The vital statistics office monitored the system as the records first started to come in and noticed that the injury description was not referring to a mudslide. When they saw that, vital register called the medical examiner’s office to ask them to include the word “mudslide” in the injury description. Because of this experience, WA is considering adding a checkbox for a disaster to the EDRS system.

- In 2013, when tornadoes hit Moore, OK, early media reports indicated the death toll was as high as 91, but this was quickly revised to 24 people thanks to the state’s EDRS capability to promptly recognize duplicates.

- In 2012, the New York City Bureau of Vital Statistics used EDRS to track deaths in near real-time during Hurricane Sandy. They found 40 people drowned in their homes located in the mandatory evacuation zone. These data were used to support efforts to improve evacuation messaging.

Key steps in making change happen

Noe, working closely with NCHS and OPHPR, has accomplished several key activities to advance the use and data quality in the various state-based electronic systems, such as the following:

- Launched a national webinar reaching more than 900 practitioners: The webinar, titled “Leveraging Electronic Death Registration System (EDRS) for “Real-time” Disaster-related Mortality Surveillance” had Vital Statistics (VS) Directors from New York City, Oklahoma, and Alabama present their recent experiences using their EDRS for disaster-related mortality surveillance. The webinars were presented monthly from February-October 2014 and have reached more than 900 public health professionals, including staff in health departments and VS offices, EDRS managers, Funeral Directors, mass fatality staff, EDRS vendors, Public Health Preparedness Directors, and hospital preparedness officials.

- Supported enhancements to EDRS in 12 states: With support and technical assistance from CDC’s Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response (OPHPR)and NCHS, the states developed strategies to make mortality data more timely, accurate, and useful. This is the case not only for administering death records, but also for applied public health programs, such as tracking mortality during a disaster, or for flu and pneumonia surveillance. Site visits by CDC allowed for VS and public health preparedness directors to discuss and plan how to enhance the timeliness of vital statistics data collection and sharing during emergency response.

- Secured funding for further leveraging the Electronic Death Registration System for disaster response: While EDRS is available, it has been under-utilized; however, recent influenza and pneumonia surveillance project by the NCHS found that it is possible for states to share electronic death certificate data as regularly as needed. NCHS in collaboration with NCEH was awarded OPHPR FY15 funding to explore disaster mortality records within the National Vital Statistics System and conduct a feasibility study of capturing data “near-real time” during an emergency response. If this is possible, Noe reasoned, this could dramatically improve public health’s capability to plan for and respond to events that result in local but also multi-state mass fatality events.

- Coordinated partners to standardize disaster-related death certificate improvements: CDC, the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems (NAPHSIS), the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, medical examiner/coroner associations, and state vital statistics offices are working to develop standardized disaster-related deaths certification guidance for medical examiners and coroners to improve reporting, data quality, and tracking of these deaths.

- Disaster death scene investigation project: This FY15-17 project funded by OPHPR will address the step preceding data entry into EDRS, which is improving the data recorded by death scene investigators. The death investigator gathers data at the scene used to determine if the death meets the disaster case definition, should be certified as such, and then be flagged in an EDRS system. Scene data are critical, yet there are not death scene investigation standards. This is partly due to various guidelines that target specific groups (e.g., law enforcement).

Strengthening the nation’s vital statistics pre-dates even the early epidemiology of John Snow, who used scientific methods to identify the environment in which cholera was spreading in 1854. The states, even as far back as the Virginia Colony, collected vital information of varying levels. The first birth and death statistics published by the federal government for the entire U.S. were based on information collected in 1850. The rising spread of epidemics in the mid-1800s expanded and enhanced the awareness of how valuable this kind of information can be, yet standardizing the process and information needed has always been a challenge.

CDC’s 2014 strategic plan notes the need for enhancing NVSS and establishes a goal that by 2016, 80% of death reports occurring in at least 25 states will be transmitted electronically to public health within one day of registration and to CDC/NCHS within 10 days of the event. The plan points out, “Modernizing and transforming the NVSS into a system capable of supporting near real-time public health surveillance has been a long standing desire and need.”

- Page last reviewed: May 15, 2015

- Page last updated: May 15, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir