Data and Statistics on HA-VTE

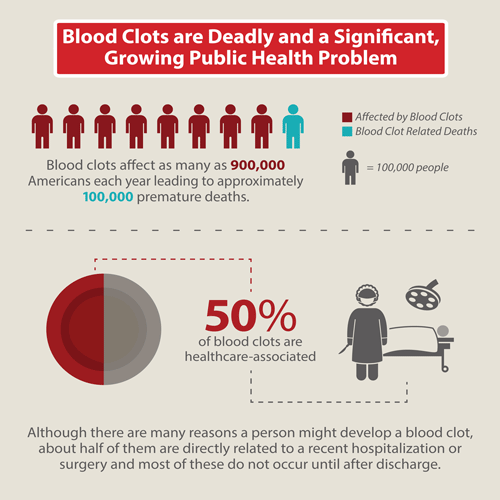

VTE is a leading cause of preventable hospital death in the United States.

- VTE is a leading cause of preventable hospital death in the United States.1

- More than half of blood clots occurring in the outpatient setting (after discharge) are directly linked to a recent hospitalization or surgery.2

- VTE is the fifth most frequent reason for unplanned hospital readmissions after surgery, overall, and the third most frequent among patients undergoing total hip or knee joint replacement.3

- As many as 70% of cases of HA-VTE are preventable through prevention measures, such as use of blood thinning medications called anticoagulants, which help prevent blood from clotting, or use of compression stockings.4-6 Yet fewer than half of hospital patients receive these measures.7

- A recent study of U.S. hospitalizations found that hospitalized adults with certain pre-existing health conditions (such as AIDS, anemia, arthritis, or congestive heart failure) are almost 3 times more likely to be diagnosed with VTE than hospitalized adults without any of these conditions.8

- A recent study of almost 500,000 surgeries performed at Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals found that about 4 in 10 patients that developed VTE after surgery had it occur while they were still in the hospital, but approximately 6 in 10 patients with VTE after surgery developed the VTE up to 90 days after having left the hospital. This finding shows that looking at hospital discharge data alone to track how often VTE occurs after surgery would lead to a serious understatement of the true size and scope of the problem.9

References

- Society of Hospital Medicine, Maynard GA, Stein JM, US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Preventing hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2008.

- Spencer F, Lessard D, Emery C, Reed G, Goldberg R. Venous thromboembolism in the outpatient setting. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1471-5.

- Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, Hall BL, Cohen ME, Williams MV, Tsai TC, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(5):483-95.

- Zeidan AM, Streiff MB, Lau BD, Ahmed SR, Kraus PS, Hobson DB, Carolan H, Lambrianidi C, Horn PB, Shermock KM, Tinoco G, Siddiqui S, Haut ER. Impact of a venous thromboembolism prophylaxis “smart order set”: Improved compliance, fewer events. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:545-9.

- Mitchell JD, Collen JF, Petteys S, Holley AB. A simple reminder system improves venous thromboembolism prophylaxis rates and reduces thrombotic events for hospitalized patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:236-43.

- Lau BD, Haut ER. Practices to prevent venous thromboembolism: a brief review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:187-95.

- Kahn S, Morrison D, Cohen J, Emed J, Tagalakis V, Roussin A, Geerts W. Interventions for implementation of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical and surgical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008201-CD.

- Tsai J, Grant AM, Beckman MG, Grosse SD, Yusuf HR, Richardson LC. Determinants of venous thromboembolism among hospitalizations of US adults: a multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0123842. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123842.

- Nelson RE, Grosse SD, Waitzman NJ, Lin J, DuVall SL, Patterson O, Tsai J, Reyes N. Using multiple sources of data for surveillance of postoperative venous thromboembolism among surgical patients treated in Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals. Thromb Res. 2015;135(4):636-42.

- Page last reviewed: April 6, 2017

- Page last updated: September 28, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir