Scarlet Fever

Scarlet fever is caused by Streptococcus pyogenes, which is also called group A Streptococcus or group A strep. The etiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment options, prognosis and complications, and prevention are described below.

Etiology

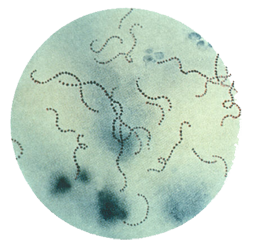

Scarlet fever is an illness caused by pyrogenic exotoxin-producing S. pyogenes. S. pyogenes are gram-positive cocci that grow in chains (see figure 1). They exhibit β-hemolysis (complete hemolysis) when grown on blood agar plates. They belong to group A in the Lancefield classification system for β-hemolytic Streptococcus, and thus are also called group A streptococci.

Clinical Features

Scarlet fever, also called scarlatina, is characterized by a scarlatiniform rash and usually occurs with group A strep pharyngitis, although it can also follow group A strep pyoderma or wound infections.

Figure 1. Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus) on Gram stain. Source: Public Health Image Library, CDC

Characteristics of the rash typically include:

- Erythematous rash that blanches on pressure

- Sandpaper quality

- Accentuation of the red rash in flexor creases (i.e., under the arm, in the groin), termed “Pastia’s lines”

- Begins on the trunk, then quickly spreads outward, usually sparing the palms, soles, and face

The rash usually persists for about one week and may be followed by desquamation. In addition, the face may appear flushed and the area around the mouth may appear pale (i.e., circumoral pallor). The tongue may be initially covered with a yellowish white coating with red papillae. The eventual disappearance of the coating can result in a “strawberry tongue.”

Transmission

Group A strep infections, including scarlet fever, are most commonly spread through direct person-to-person transmission, typically through saliva or nasal secretions from an infected person. People with scarlet fever are much more likely to transmit the bacteria to others than asymptomatic carriers. Crowded conditions — such as those in schools, daycare centers, or military training facilities — facilitate transmission. Although rare, spread of group A strep infections may also occur via food. Foodborne outbreaks of group A strep have occurred due to improper food handling. Fomites, such as household items like plates or toys, are very unlikely to spread these bacteria.

Humans are the primary reservoir for group A strep. There is no evidence to indicate that pets can transmit the bacteria to humans.

Treating a person with scarlet fever with an appropriate antibiotic for 24 hours or longer generally eliminates their ability to transmit the bacteria. People with scarlet fever should stay home from work, school, or daycare until they are afebrile and until 24 hours after starting appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Incubation Period

The incubation period of scarlet fever is approximately 2 through 5 days.

Risk Factors

Scarlet fever can occur in people of all ages, but it is most common among children 5 through 15 years of age. It is rare in children younger than 3 years of age.

The most common risk factor is close contact with another person with scarlet fever. Crowding, such as found in schools, military barracks, and daycare centers, increases the risk of disease spread.

Diagnosis and Testing

The differential diagnosis of scarlet fever with pharyngitis includes multiple viral pathogens that can cause acute pharyngitis with a viral exanthema. The diagnosis of scarlet fever with group A strep pharyngitis is confirmed by either a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) or a throat culture. RADTs have high specificity for group A strep but varying sensitivities when compared to throat culture. Throat culture is the gold standard diagnostic test. A negative RADT in a child with symptoms of scarlet fever should be followed up by a throat culture. Clinicians should have a mechanism in place to contact the family and initiate antibiotics if the back-up throat culture is positive.

See the resources section for specific diagnosis guidelines for adult and pediatric patients1,2,3.

Treatment

The use of a recommended antibiotic regimen to treat scarlet fever shortens the duration of symptoms; reduces the likelihood of transmission to family members, classmates, and other close contacts; and prevents the development of complications, including acute rheumatic fever.

Penicillin or amoxicillin is the antibiotic of choice to treat scarlet fever. There has never been a report of a clinical isolate of group A strep that is resistant to penicillin. For patients with a penicillin allergy, recommended regimens include narrow-spectrum cephalosporins (e.g., cephalexin, cefadroxil), clindamycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin.

See the resources section for specific treatment guidelines for adult and pediatric patients1,2,3.

Table: Antibiotic Regimens Recommended for Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis

| Drug, Route | Dose or Dosage | Duration or Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| For individuals without penicillin allergy | ||

| Penicillin V, oral | Children: 250 mg twice daily or 3 times daily; adolescents and adults: 250 mg 4 times daily or 500 mg twice daily | 10 days |

| Amoxicillin, oral | 50 mg/kg once daily (max = 1000 mg); alternate: 25 mg/kg (max = 500 mg) twice daily |

10 days |

| Benzathine penicillin G, intramuscular | <27 kg: 600 000 U; ≥27 kg: 1 200 000 U | 1 dose |

| For individuals with penicillin allergy | ||

| Cephalexin,a oral | 20 mg/kg/dose twice daily (max = 500 mg/dose) | 10 days |

| Cefadroxil,a oral | 30 mg/kg once daily (max = 1 g) | 10 days |

| Clindamycin, oral | 7 mg/kg/dose 3 times daily (max = 300 mg/dose) | 10 days |

| Azithromycin,b oral | 12 mg/kg once daily (max = 500 mg) | 5 days |

| Clarithromycinb, oral | 7.5 mg/kg/dose twice daily (max = 250 mg/dose) | 10 days |

Abbreviation: Max, maximum.

a Avoid in individuals with immediate type hypersensitivity to penicillin.

b Resistance of group A strep to these agents is well-known and varies geographically and temporally.

From: Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):e86–e102, Table 2 (adapted).

Note: If you are interested in reusing this table, permission must first be given by the journal; request by emailing journals.permissions@oup.com.

Prognosis and Complications

Rarely, complications can occur after scarlet fever. Scarlet fever can have the same suppurative and non-suppurative complications as group A strep pharyngitis. Suppurative complications result from local or hematogenous spread of the organism. They can include peritonsillar abscesses, retropharyngeal abscess, cervical lymphadenitis, and invasive group A strep disease.

Nonsuppurative sequelae of group A strep infections include acute rheumatic fever (after group A strep pharyngitis) and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (after group A strep pharyngitis or skin infections). These complications occur after the original infection resolves and involve sites distant to the initial site of group A strep infection. They are thought to be the result of the immune response and not of direct group A strep infection.

Prevention

The spread of all types of group A strep infections, including scarlet fever, can be reduced by good hand hygiene, especially after coughing and sneezing and before preparing foods or eating, and respiratory etiquette (e.g., covering your cough or sneeze). Treating an infected person with an antibiotic for 24 hours or longer generally eliminates their ability to transmit the bacteria. Thus, people with scarlet fever should stay home from work, school, or daycare until afebrile and until at least 24 hours after starting appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Epidemiology and Surveillance

Humans are the only reservoir for group A strep. In the United States, scarlet fever is most common during the winter and the age distribution is similar to that of group A strep pharyngitis (i.e., most common among children 5 through 15 years of age; rare in children younger than 3 years of age). However, CDC does not track the incidence of scarlet fever or other non-invasive group A strep infections. CDC tracks invasive group A strep infections through the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program. For information on the incidence of invasive group A strep infections, please visit the ABCs Surveillance Reports website.

Resources

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1279–82.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases. Group A streptococcal infections. In Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, editors. 30th ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village (IL). American Academy of Pediatrics. 2015;732–44.

- Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, Gewitz M, Rowley AH, Shulman ST, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: Endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Related Pages

- Page last reviewed: September 16, 2016

- Page last updated: September 16, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir