Rosemary’s Journey: Kenya’s First Medically Assisted Therapy Program to Reduce HIV Transmission among People Who Inject Drugs

Dr. Mercy Karanja meets with Rosemary to discuss her treatment.

"PEPFAR, through CDC and University of Maryland (UoM) [CDC Kenya’s implementing partner], has been of great assistance in the implementation of services,” says Dr. Mercy Karanja, clinical director at the Mathari Hospital MAT clinic. “The clinic was renovated and equipped through PEPFAR support and, due to shortage of staff, UoM has hired eight additional staff to assist the existing government staff. CDC also supported training and capacity building and study tours to other methadone clinics in Tanzania and Baltimore. UoM has provided mentorship, and the clinic continues to receive supplies for laboratory and office supplies as well as maintenance of the equipment through PEPFAR funding."

Rosemary traces the scar on her right hand where she used to inject heroin, recounting her 25 years of addiction to the opioid drug. “Sometimes I would miss the vein when I injected myself,” she recalls. In 2012 she developed a severe infection in her hand. “The doctors said they might have to amputate.”

In one of the clinical rooms at the Medically Assisted Therapy (MAT) clinic at Mathari National Teaching and Referral Hospital, Rosemary recounts the toll that heroin took on her mental and physical health, and her relationship with her family. The clinic, supported by CDC Kenya through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), is the first in Kenya to provide treatment services for people who inject drugs (PWID) who are at increased risk for bloodborne diseases like HIV and hepatitis B and C.

The Long Road of Addiction

Rosemary’s injecting drug use began early in life. Growing up in poverty, she left home in 1989 at the age of 18. Her elder sister moved to Mombasa, and Rosemary followed. As a poor young woman with limited prospects, she looked for support and met a man, a foreigner, who took her in. He also introduced her to heroin.

She wondered what he was using that seemed to make him feel so good. He said, “It’s something good. Do you want to try it?”

At first she only smoked heroin and enjoyed it. Then her boyfriend suddenly left her, returning to his home country. By that time, she was addicted.

Without support, she moved to a cheaper neighborhood and began stealing from others, including her sisters. Aware she was using heroin, her neighbors and family eventually chased her away. From there, life was a downward spiral, eventually leading to living in drug dens, engaging in sex work, and conning people to pay for her habit.

“This life was very hard,” Rosemary says quietly.

Around 2002, smoking was no longer getting Rosemary as high as she wanted. A friend said that injecting the drug would get her higher. The greater high from injecting made it less expensive than smoking heroin.

Like many people who use heroin, Rosemary spent many years cycling through drug use and attempts to quit with significant consequences to her health. In 2006, she began exhibiting psychiatric symptoms and was admitted to a psychiatric facility for six months. But she went back to using drugs, and from 2006 to 2012, she was back on the streets.

Many times, Rosemary wanted to quit using drugs, but when she tried to stop, she experienced arosto (withdrawal).

It was in 2012 that she developed the severe abscess on her hand. She asked her sister for forgiveness and support to come to Nairobi. She moved in with her mother who had cancer and had recently had a stroke. Since she was still dressing her wound, she could not inject drugs, but the desire to use drugs overwhelmed her and she returned to smoking heroin.

A Turning Point

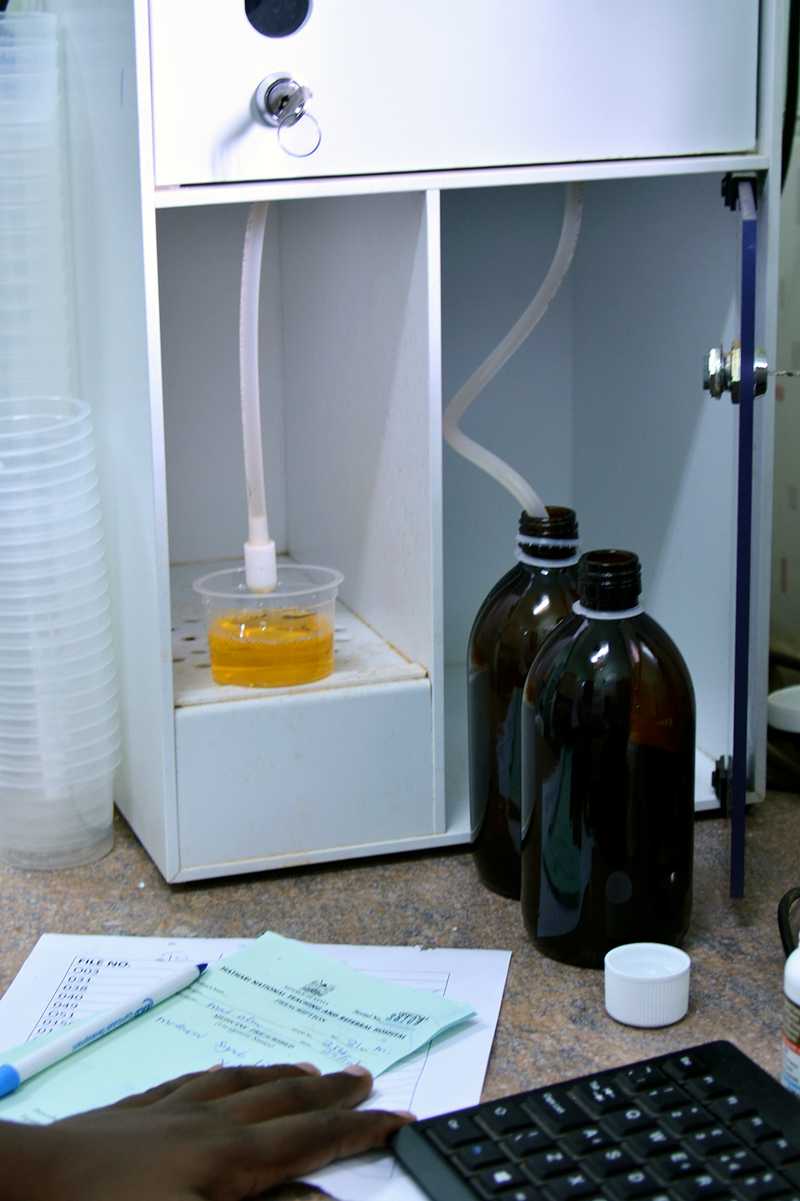

Each day, Rosemary and other clients of the Medically Assisted Therapy program come to this window at the clinic to get their prescribed dose of methadone.

Rosemary first heard about methadone, the drug used to treat those withdrawing from opioid drugs like heroin, while she was in the drug dens.

She saw a friend named Richard who used to inject heroin six times a day. He was taking methadone, and she saw that he was changed.

He said, “When you take it, you can’t feel the arosto.”

He said he could do anything now that he was not on drugs and encouraged her to quit smoking. He came to the drug dens to continue talking to people and answer their questions about methadone.

Rosemary felt she didn’t have a choice any longer. The dens were a terrible place to live. The rooms were dirty; the beds had bed bugs.

An outreach worker came to the dens and asked, “How long are you going to live here? You’re wearing dirty clothes. You don’t shower and you smell. Your shoes don’t even match.”

The Path to Recovery

In January 2015, she was brought to the outpatient MAT clinic at Mathari Hospital, which had just started enrolling patients on December 4, 2014.

“PEPFAR through CDC and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) worked collaboratively with the Government of Kenya to get approval to initiate the use of methadone as a public health intervention for HIV prevention,” explains Mercy Muthui, a CDC Kenya public health specialist for HIV prevention programs. Civil society organizations (CSOs) that support PWIDs have also played a significant role by linking clients to the MAT program.

Each dose of methadone is precisely measured by the clinic’s staff.

Rosemary was surprised to see that the methadone was a liquid. Initially she was given 30 milligrams (mg), but later her dose was increased to 40 mg.

That took away Rosemary’s withdrawal symptoms. Her appetite increased and she slept well.

Dr. Mercy Karanja, clinical director of the Mathari Hospital MAT clinic, describes the program, “The recommended duration on methadone maintenance is a minimum of 24 months after which clients can be gradually weaned off methadone. Some may continue on methadone for a much longer duration depending on psychosocial circumstances, underlying comorbid illness, and an individual’s motivation.”

Rosemary worried that methadone might make her high, but it was very good. She felt the need to be clean, and she made her bed.

“I thank God for methadone,” says Rosemary.

However, she was still worried that her family would never trust her again. She had doubts that they would accept her, but she went back to her mother’s home.

By this time her mother was not able to speak due to her stroke, but when she heard Rosemary’s voice, she hit the door to tell her sister that she wanted Rosemary to come in. Not only did they accept her, they were very happy to see her.

She vowed she wouldn’t hurt her mother again.

Rosemary’s Future

The Medically Assisted Therapy program at Mathari Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya, offers comprehensive services for People Who Inject Drugs, including:

- Methadone maintenance therapy

- HIV counseling and testing (17% of the clinic’s MAT clients are HIV positive)

- Antiretroviral therapy

- TB testing and treatment

- Hepatitis B & C testing and vaccination for Hepatitis B

- Testing and treatment of other sexually transmitted illnesses

- Mental state assessment and treatment

- General medical treatment such as wound and abscess care

- Condom demonstration and distribution

- Psychosocial intervention including counselling, family reintegration, occupational therapy

- By referral: antenatal care and family planning

The MAT program at Mathari Hospital is creating a future for many who, like Rosemary, seemed lost to their families and communities. In its first 15 months of operation, the clinic has enrolled over 570 patients and 84% have remained in the program.

What is Rosemary’s hope for her future? She would like to get a job as a peer educator and reach out to others, or to start her own business.

Initially, she had a job cleaning for one of the CSOs that support PWIDs, but the funding ran out. Now she works odd jobs to support her family.

Her concern is that, when people are idle, they will go back to using drugs. “We do need to keep busy.”

“One of the biggest challenges that the clients face during their recovery is lack of economic empowerment opportunities,” notes Dr. Karanja. “Most of them had already lost their jobs or failed to complete their studies during their active drug dependence days and were engaged in criminal activities to sustain their addiction. As part of their recovery, they desire to be engaged in economically productive work but lack the opportunities. While the clinic does not have sustainable livelihood projects for the clients, the occupational therapist encourages them to learn skills such as bead or leather work.”

Methadone has changed Rosemary. She now helps take care of her mother and younger sister. She goes to the drug dens to talk to those who are still drug dependent and dispels myths about methadone treatment. She tells them that methadone works.

Rosemary also helped form a group that goes to churches to give testimony about their recovery from drug use. And she has asked for forgiveness in church and from people whom she hurt in the past.

“It’s a big change,” says Rosemary. For her, the transformation has given her hope and her life back.

“Methadone is magic!”

Related Links

- Page last reviewed: March 22, 2016

- Page last updated: April 1, 2016

- Content source:

Global Health

Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir