Patients Face More Lethal Infections from CRE

Some germs are beating even our strongest antibiotics. Rapid action by clinicians and healthcare leaders is needed to stop the rise of lethal CRE infections.

Some germs are beating even our strongest antibiotics. Rapid action by clinicians and healthcare leaders is needed to stop the rise of lethal CRE infections.

A 2013 Vital Signs report shows that antibiotics are being overpowered by lethal germs called carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE).These germs cause lethal infections in patients receiving inpatient medical care, such as in hospitals, long-term acute care facilities, and nursing homes.

In their usual forms, germs from the Enterobacteriaceae family (e.g. E. coli) are a normal part of the human digestive system. However, some of these germs have developed defenses to fight off all or almost all antibiotics we have today.When these germs get into the blood, bladder or other areas where germs don't belong, patients suffer from infections that are difficult, and sometimes impossible, to treat.

Untreatable and hard-to-treat infections from CRE germs are on the rise among patients in medical facilities.

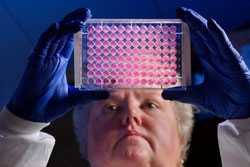

CDC’s Kitty Anderson holds up a 96-well plate used for testing the ability of bacteria to growth in the presence of antibiotics.

While CDC has warned about CRE for more than a decade, new information shows that these germs are now becoming more common. One type of CRE has been detected in medical facilities in 42 states. Even more concerning, this report documents a seven-fold increase in the spread of the most common type of CRE during the past 10 years.

Why are CRE so alarming?

Even though these infections are not common, their rise is alarming because they kill up to half of people who get severe infections from them. In addition to causing lethal infections among patients, CRE are especially good at giving their antibiotic-fighting abilities to other kinds of germs.This means that in the near future, more bacteria will become immune to treatment, and more patients' lives could be at risk from routine bladder or wound infections. Without serious efforts to stop CRE in medical facilities, and without rapid improvement in the way doctors everywhere prescribe antibiotics, CRE will likely become a problem in the community, among otherwise healthy people not receiving medical care.

How can CRE be stopped?

There have been major successes in stopping CRE in medical facilities in the United States, and nationally in other countries. Stopping CRE will take a rapid, coordinated, and aggressive "Detect and Protect" action that includes intense infection prevention work and antibiotic prescribing changes. CDC released a CRE prevention toolkit reiterating practical CRE prevention and control steps. Leadership and medical staff in hospitals, long-term acute care hospitals, nursing homes, health departments, and even outpatient practices must work together to implement these recommendations to protect patients from CRE.

Outbreaks highlight the importance of CDC and state health departments working collaboratively to identify and stop spread of antibiotic resistant pathogens. In the FY 16 budget, CDC has requested funding to support State Antibiotic Resistance Prevention Programs [370 KB] in all 50 states and 10 large cities and a regional lab network [275 KB] to help identify and to respond faster to outbreaks. This funding would provide critical national infrastructure to prevent the growing threat of CRE and other drug-resistant pathogens.

- Page last reviewed: February 20, 2015

- Page last updated: February 20, 2015

- Content source:

- National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion

- Page maintained by: Office of the Associate Director for Communication, Digital Media Branch, Division of Public Affairs

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir