Content on this page was developed during the 2009-2010 H1N1 pandemic and has not been updated.

- The H1N1 virus that caused that pandemic is now a regular human flu virus and continues to circulate seasonally worldwide.

- The English language content on this website is being archived for historic and reference purposes only.

- For current, updated information on seasonal flu, including information about H1N1, see the CDC Seasonal Flu website.

2009 H1N1 and Seasonal Influenza and Hispanic Communities: Questions and Answers

February 16, 2010, 2:20 PM ET

On this Page

- What impact is 2009 H1N1 having on Hispanic communities?

- What factors contribute to 2009 H1N1's impact on Hispanic communities?

- What can we do to prevent 2009 H1N1 and seasonal flu?

- What is the influenza vaccination coverage in the Hispanic population?

- What perceptions, behaviors and barriers affect vaccine uptake?

- What are some strategies for increasing 2009 H1N1 and seasonal vaccine coverage in Hispanic communities?

- Increase the number, accessibility, and use of vaccination sites

- Communicate what is known about vaccine safety and effectiveness

- Improve the collection and use of data

- More Info: Links

- References

Since April 2009, the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus has been spreading from person-to-person worldwide, affecting all racial and ethnic groups. This 2009 H1N1 and Seasonal Flu and Hispanic Communities: Questions and Answers document summarizes current understanding of the impact of 2009 H1N1 and seasonal influenza viruses on Hispanics, describes some of the barriers to uptake of 2009 H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccines, and outlines potential strategies for improving health and increasing vaccine coverage in Hispanic communities.

2009 H1N1 and seasonal influenza materials for all individuals are available in English and Spanish at www.flu.gov, www.cdc.gov and www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu.

What impact is 2009 H1N1 having on Hispanic communities?

2009 H1N1 and seasonal flu data on racial and ethnic groups have been taken from a wide range of sources and geographic areas and show differing results. For instance:

- Although Hispanics comprise approximately 15% of the US population, 1 they were overrepresented in the enhanced surveillance case reports during the early spring wave of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, comprising about 30% of all reported cases.2 This is not unexpected since 2009 H1N1 was first identified in US cities with large Hispanic populations.

- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data from household interviews conducted from September 1st – November 30, 2009 show self-reported influenza-like illness and having sought medical care for that illness was similar among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white respondents.3

- From April 15 - August 31, 2009, 15 percent of people hospitalized with 2009 H1N1 in 13 metropolitan areas of 10 states were Hispanic. Approximately 13 percent of the catchment area population studied is Hispanic.2 Of note, in previous influenza seasons Hispanics without underlying medical conditions were overrepresented in hospitalized cases (ranging from 16 – 25% of cases without an underlying medical condition).

- From April, 2009 – December 31, 2009, laboratory-confirmed 2009 H1N1 hospitalization rates were almost 2.5 times higher for Hispanics (31.5/100,000) compared to non-Hispanic whites (12.7/100,000) in the State of Illinois. The disparity in hospitalization rates was even greater for Hispanic children less than 5 years old (89/100,000) compared to non-Hispanic white children of the same age (29.1/100,000).4

- From May 19 – June 30, 2009, Hispanic residents of Salt Lake County, Utah with confirmed 2009 H1N1 infection were 2.8 more likely to require hospitalization in the intensive care unit compared to non-Hispanic whites.5

- Hispanic children younger than 18 years of age account for 27% of 210 reported 2009 H1N1 influenza-associated deaths in the United States.6 Their representation in the US population is 21%.7

What factors contribute to 2009 H1N1’s impact on Hispanic communities?

Rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations and deaths vary among different age groups and across influenza seasons.8

The age distribution of the Hispanic population is very different from that of the non-Hispanic white population.7 The median age of the Hispanic populations, 26.9 years, is approximately 13 years younger than that of the non-Hispanic white population.9 The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic is primarily affecting a young population with more than 50% of hospitalized cases in persons younger than 25 years old.

Many medical conditions are associated with an increased risk of complications from influenza. Disparities in certain underlying high-risk conditions, such as diabetes, pregnancy and asthma, may contribute to the impact of 2009 H1N1 on Hispanic communities.

From April 2009 – September 2009:

- Approximately 10 percent of people hospitalized with complications from 2009 H1N1 influenza have been diabetic. Among adults 20 years of age and older, diabetes is more prevalent among Hispanics (10%), with the highest prevalence rates among Mexican Americans (12%) and Puerto Ricans (13%), compared with non-Hispanic whites (7%).10

- Pregnant women represent approximately 6% of confirmed 2009 H1N1 hospitalized cases and deaths although they represent only 1% of the general population. The fertility rate is higher for Hispanic women (101.5/1000) than for non-Hispanic white women (59.5/1000).11

- Almost one-third of people hospitalized with complications from 2009 H1N1 influenza to date have been persons with asthma. Hispanics 15 years of age and over have a lower prevalence of asthma (5.4%) than non-Hispanic whites 15 years of age and over (8.0%).12

There is no epidemiological or clinical evidence that suggests that Hispanics are more susceptible to either 2009 H1N1 or seasonal influenza or to poorer health outcomes by virtue of their race alone. Therefore, further investigation is essential to more clearly elucidate factors that might contribute to disproportionate influenza-associated hospitalization and pediatric mortality among Hispanics.

What can we do to prevent 2009 H1N1 and seasonal flu?

CDC recommends a three-step approach for everyone to fight the flu

- Get vaccinated;

- Take everyday preventive actions, including covering coughs and sneezes, frequent hand washing, and staying home when sick; and

- Use antiviral drugs correctly if your doctor recommends them.

What is the influenza vaccination coverage in the Hispanic population?

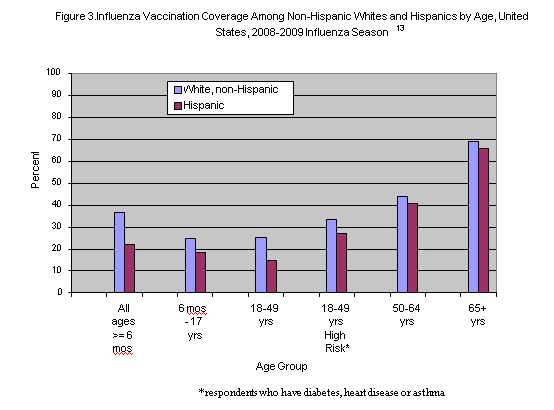

Although the most effective way to prevent both 2009 H1N1 and seasonal influenza and their complications is to be vaccinated, overall 2008-2009 seasonal influenza vaccination coverage was low across racial and ethnic groups (figure 3). Further, many Hispanics were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive influenza vaccination.13

Disparities in vaccination coverage are also evident this influenza season. As of mid-December, 2009, only 24.7% of Hispanic adults had received seasonal influenza vaccine compared to 38.6% of non-Hispanic white adults.3 No significant differences were seen in cumulative 2009 H1N1 vaccination coverage by race/ethnicity among adults overall.14

What perceptions, behaviors and barriers affect vaccine uptake?

Intent to get vaccinated:

- Many Hispanics intend to obtain seasonal and 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccinations for themselves and their children. In a national poll conducted by C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital in August 2009, 52% of Hispanic parents planned to obtain H1N1 Flu vaccination for their children compared to 38% of non-Hispanic white parents.15

- Similarly, in a recent online survey, 46% of Hispanic parents indicated their intent to obtain 2009 H1N1 vaccination for their children compared to 32% of non-Hispanic white parents. A higher percent of Hispanic respondents (42%) also intended to obtain 2009 H1N1 vaccination for themselves compared to non-Hispanic whites (28%), but no difference was found related to intent to obtain seasonal flu vaccination (43%, 44% respectively).16

Health-care seeking-behavior

- Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries (25.9%) were 40% less likely than Non-Hispanic white Medicare beneficiaries (42%) to have a vaccination-initiated visit.17

- Marginalized Hispanic populations (non-English speakers, migrant workers, undocumented, and those living in rural and undeveloped areas) are unlikely to access health care services except in emergency situations.18

Barriers:

- Socioeconomic disparities among racial/ethnic groups may impact ability to access health care and obtain recommended vaccinations and treatment. According to the 2009 Current Population Report,19 23% of Hispanics were living below poverty level in 2008 and 31% of Hispanics were uninsured in 2008.

- Language barriers may interfere with one’s ability to access services and comprehend health education messages.9

- Undocumented residency status may deter some Hispanics from seeking vaccinations for fear of being required to provide proof of legal status in order to receive vaccine. 20

What are some strategies for increasing 2009 H1N1 and seasonal vaccine coverage in Hispanic communities?

Promotion of 2009 H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccinations in Hispanics is a key part of the response. Vaccination campaigns should be inclusive and transparent, engaging all stakeholders in the Hispanic community in order to more effectively address community concerns, and to inform and educate the public.21 Faith-based organizations, health “promotores/as”, Spanish-language media including radio, TV and web-based outlets, and the dissemination of culturally and linguistically appropriate health educational materials have been effectively utilized in other community health campaigns in the Hispanic community.

Increase the number, accessibility, and use of vaccination sites.

It is important to continue to increase the number, accessibility of, and use of vaccination sites, particularly within underserved communities. Availability of low-cost and free 2009 H1N1 vaccine to all residents, regardless of legal status, and at non-traditional sites (such as pharmacies) should be broadly communicated in the Hispanic community.

Communicate what is known about vaccine safety and effectiveness.

Vaccine coverage will improve with increased awareness that:

- Both the 2009 H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccines are safe.

- The 2009 H1N1 vaccine is made the same way as the seasonal vaccine that has been used safely and successfully for many years.

- CDC and FDA believe that the benefits of vaccination with the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine will far outweigh the risks.

- Both seasonal and 2009 H1N1 vaccines reduce risk of serious complications from influenza for people with certain underlying medical conditions and for the very young and the elderly.

Improve the collection and use of data.

Hispanics are a diverse population with varying degrees of cultural assimilation in the United States. Therefore, it is important to determine feasibility of incorporating Hispanic ancestry, nativity, and English language fluency into current data collection tools. It is also important to analyze influenza-associated hospitalizations, deaths, and influenza vaccine coverage for the different subpopulations of Hispanics. In addition, analyses of age-specific hospitalization and mortality rates by race/ethnicity would be especially useful in analyzing disparities among racial/ethnic populations with very different age distributions from that of non-Hispanic whites. Further investigation is also recommended to identify contributory factors to the overrepresentation of Hispanics among influenza-associated hospitalized patients without an underlying medical condition that is known to increase risk for complications from influenza.

What are some useful links for more information?

H1N1 Flu: General InformationReferences

- U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Table 3: Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008 (NC-EST2008-03). Release Date: May 2009.

- CDC. Emerging Infections Program. Unpublished data.

- CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009. Unpublished data.

- Illinois Department of Public Health, 2009. Unpublished data.

- Miller RR 3rd et al. Clinical findings and demographic factors associated with intensive care unit admission in Utah due to 2009 novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Chest. Prepublished online Nov 20 2009. DOI 10.1278/chest.09-2517.

- CDC. Nationally Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. Surveillance for Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality, 2009. Unpublished data.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2008. Internet release date: September 2009.

- CDC. Use of Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Monovalent Vaccine Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009 Aug 21; 58(Early Release); 1-8.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Reports, The American Community—Hispanics, 2004, ACS-03, Issued February 2007. Accessed 7, Dec 2009.

- CDC. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States, 2007. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008.

- CDC. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2008. Accessed 22, December 2009.

- CDC. Barnes PM, Schiller JS, Heyman KM. Early release of selected estimates based on data from January-June 2009 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. December 2009.

- CDC. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Children and Adults ---United States, 2008-2009 Influenza Season. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009 Oct 9; 58(39):1091-5.

- CDC. Interim Results – Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Monovalent Vaccination Coverage – United States, October – December 2009, 2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Jan 22; 59(2); 44-48.

- C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. National Poll on Children’s Health. Vol. 8 Issue 1, September 24, 2009. Accessed 28 November 2009.

- CDC. H1N1: Perception of Risk, Attitudes Towards Vaccine and Motivating Messages for African-American and Hispanic Consumers, Online Survey, October 2009. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Unpublished data.

- Herbert, Paul L, Frick, Kevin D, Kane, Robert L, McBean, A. Marshall. Causes of Racial and Ethnic Differences in Influenza Vaccination Rates. Health Services Research 40:2 (April 2005).

- Barriers to and Facilitators of Effective Risk Communication Among Hard-to-Reach Populations in the Event of a Bioterrorist Attack or Outbreak, Feb 2004. Publication #19-11984. Texas Department of Health.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-236, Income, Poverty and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2008, Issued September 2009. Accessed 7, December 2009.

- CDC. Sector-Specific Partner Outreach and Engagement Project-Top of Mind Summary Latino Faith, November 6, 2009. Report compiled by ICF Macro, an ICF International Company.

- Hutchins SS, et al. Protection of Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations during an Influenza Pandemic. Am J Public Health 2009; Suppl: S261-S270.

Get email updates

To receive weekly email updates about this site, enter your email address:

Contact Us:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Rd

Atlanta, GA 30333 - 800-CDC-INFO

(800-232-4636)

TTY: (888) 232-6348 - Contact CDC-INFO