Chapter 2: Public Health Assessment Overview

- (Section 2.1) What is a public health assessment?

- (Section 2.2) When is a public health assessment conducted?

- (Section 2.3) Who conducts public health assessments?

- (Section 2.4) What is the role of the community in a public health assessment?

- (Section 2.5) How is the public health assessment conducted?

- (Section 2.6) What products and public health actions result from the assessment process?

- (Section 2.7) What is the format for public health assessment documents?

This chapter introduces the public health assessment process and serves as a road map to the rest of the manual. It provides an overview of the various steps in the process, introduces the multi-disciplinary team approach that you will use for most of your public health assessments, and describes the specific role of the health assessor and team leader and how various team members fit into the process. Throughout this manual, the public health assessment process will be distinguished from the public health assessment document. Henceforth, the acronym "PHA" will be used exclusively to refer to the PHA document (whereas, the public health assessment process can result in either a PHA or a PHC).

ATSDR partners may find that some discussions in this chapter, and the manual in general, are not necessarily relevant to their particular procedures (e.g., use of affiliated offices to manage different aspects of the public health assessment), but the process as a whole applies to all health assessors from within or outside ATSDR. This chapter addresses the questions:

2.1 What Is a Public Health Assessment?

A public health assessment is formally defined as:

The evaluation of data and information on the release of hazardous substances into the environment in order to assess any [past], current, or future impact on public health, develop health advisories or other recommendations, and identify studies or actions needed to evaluate and mitigate or prevent human health effects (42 Code of Federal Regulations, Part 90, published in 55 Federal Register 5136, February 13, 1990).

A public health assessment is conducted to determine whether and to what extent people have been, are being, or may be exposed to hazardous substances associated with a hazardous waste site and, if so, whether that exposure is harmful and should be stopped or reduced. The public health assessment process enables ATSDR to prioritize and identify additional steps needed to answer public health questions, and defines follow-up activities needed to protect public health.

There are a number of goals of the process that you should keep in mind throughout your assessment. These are:

- Evaluate site conditions and determine the nature and extent of environmental contamination.

- Define potential human exposure pathways related to site-specific environmental contaminants.

- Identify who may be or may have been exposed to environmental contamination associated with a site (past, current, and future).

- Examine the public health implications of site-related exposures, through the examination of environmental and health effects data (toxicologic, epidemiologic, medical, and health outcome data).

- Address those implications by recommending relevant public health actions to prevent harmful exposures.

- Identify and respond to community health concerns and clearly communicate the findings of the assessment.

2.1.2 Factors to Be Considered in All Public Health Assessments

By law, ATSDR is required to consider certain factors when evaluating possible public health hazards. Specifically, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), as amended by the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA) (104 [i][6][f]) requires that, at a minimum, public health assessments consider the following factors. This manual describes an approach to conducting public health assessments that incorporates each of them.

- Nature and extent of contamination—What is the spatial and temporal extent of site-related contamination? Have contaminants migrated off site? What media have been and/or continue to be affected (e.g., water, soil, air, food chain [biota])?

- Demographics (population size and susceptibility)—Who is being exposed, and do any special populations need to be considered (e.g., children, women of child-bearing age, fetuses, lactating women, the elderly)?

- Pathways of human exposure (past, current, and future)—How might people be exposed to site-related contamination (e.g., drinking water, breathing air, direct skin contact)? What are the site-specific exposure conditions (e.g., duration, frequency, and magnitude of exposure)?

- Health effects and disease-related data—How do expected site-specific exposure levels for the identified hazardous substances compare with the observed health effect levels (from toxicologic, epidemiologic, and medical studies), and with any available recommended exposure or tolerance limits (e.g., water quality standards)? How do existing morbidity and mortality data on diseases compare with observed levels of exposure?

2.1.3 How Does a Public Health Assessment Differ From a Risk Assessment?

ATSDR's public health assessments differ from the more quantitative risk assessments conducted by regulatory agencies, such as EPA. Both types of assessments attempt to address the potential human health effects of low-level environmental exposures, but they are approached differently and are used for different purposes. One needs to understand these differences to know how to interpret and integrate the information generated by each of these assessments.

- The quantitative risk assessment is used by regulators as part of site remedial investigations to determine the extent to which site remedial action (e.g., cleanup) is needed. The risk assessment provides a numeric estimate of theoretical risk or hazard, assuming no cleanup takes place. It focuses on current and potential future exposures and considers all contaminated media regardless if exposures are occurring or are likely to occur. By design, it generally uses standard (default) protective exposure assumptions when evaluating site risk.

- The public health assessment is used by ATSDR to identify possible harmful exposures and to recommend actions needed to protect public health. ATSDR considers the same environmental data as EPA, but focuses more closely on site-specific exposure conditions, specific community health concerns, and any available health outcome data to provide a more qualitative, less theoretical evaluation of possible public health hazards. It considers past exposures in addition to current and potential future exposures.

The general steps in the two processes are similar (e.g., data gathering, exposure assessment, toxicologic evaluation), but the public health assessment provides additional public health perspective by integrating site-specific exposure conditions with health effects data and specific community health concerns. ATSDR's public health assessment also evaluates health outcome data, when available, to identify whether rates of disease or death are elevated in a site community, especially if the community expresses concern about a particular outcome (e.g., cancer).

Remedial plans based on a quantitative risk assessment represent a prudent public health approach—that of prevention. By design, however, quantitative risk assessments used for regulatory purposes do not provide perspective on what the risk estimates mean in the context of the site community. The public health assessment does. The process is more exposure driven. The process identifies and explains whether exposures are truly likely to be harmful under site-specific conditions and recommends actions to reduce or prevent such exposures.

2.2 When Is a Public Health Assessment Conducted?

Three situations can trigger a public health assessment:

- A site is proposed to be placed on the EPA National Priorities List (NPL). ATSDR is required by law to conduct a public health assessment at all sites proposed for or listed on EPA's NPL.

- ATSDR receives a "petition" to evaluate a site or release. Both CERCLA, as amended by SARA, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), as amended by the Hazardous Solid Waste Amendments of 1984, allow individual and concerned parties (e.g., community members, physicians, state or federal agencies, or tribal governments) to petition ATSDR to conduct public health assessments. ATSDR has promulgated regulations describing the petitioned public health assessment process (42 Code of Federal Regulations, Part 90, published in 55 Federal Register 5136, February 13, 1990). After the initial information gathering, ATSDR decides whether a public health assessment should be conducted. Not every petition results in a public health assessment.

- ATSDR receives a request from another agency. State and federal regulatory agencies and state, local, and tribal health departments may request that ATSDR use its public health evaluation expertise to provide a technical consultation for a proposed or completed action. In these cases, ATSDR may be asked to evaluate data (e.g., a sampling plan, a remediation alternative) for the degree to which it is protective of public health. This type of evaluation is often conducted as an abbreviated public health assessment.

2.3 Who Conducts Public Health Assessments?

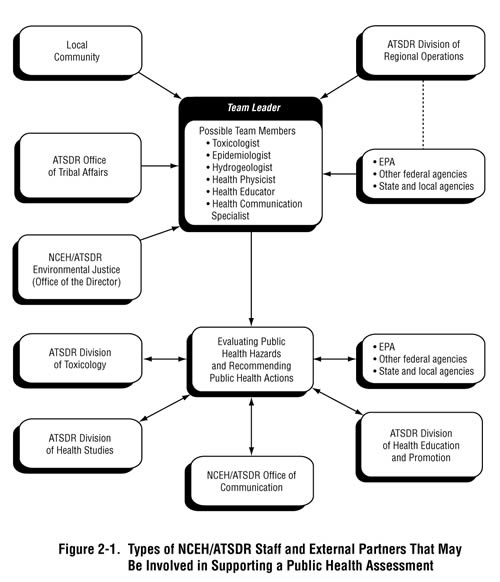

ATSDR staff and its government partners (i.e., state health departments, tribal governments, and other government organizations that have received funding through ATSDR's cooperative agreement program) are responsible for conducting public health assessments, for communicating the findings of their evaluations to the public, and for involving the community and responding to community health concerns. The process may require the coordination and cooperative efforts of ATSDR's Division of Health Assessment and Consultation (DHAC) with other offices and divisions within ATSDR; other local/county, state, and federal government agencies; tribes; and the community.

Early in the process, the team leader—generally you, the health assessor—establishes a team composed of individuals who contribute to the site-specific technical and communication needs of the site. Experience has shown that a team approach is very effective, especially at more complex sites. The mix of the team will depend on the nature and complexity of site issues and may change over the course of the assessment as more information becomes available. Team members may include scientists (e.g., engineers, environmental or public health scientists, geologists, toxicologists, epidemiologists, health physicists), communication specialists, health educators, and/or medical professionals.

Those who support the assessment will vary from site to site. Regional representatives from the agency's Division of Regional Operations should be included on site teams. The regional representative is a vital link between ATSDR; federal, state, and tribal partners; and the community. For many sites, your team may require a health communication specialist to ensure that appropriate community involvement and outreach mechanisms are established. Where tribal issues are identified or if assistance is needed in identifying tribal concerns, ATSDR's Office of Tribal Affairs (OTA) will be contacted (see Appendix A for policies governing ATSDR's relationship with tribal governments and Section 4.2.3 for further information about OTA). When environmental justice concerns exist, the National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH)/ATSDR's Office of Director/Environmental Justice may become involved (see Section 4.2.4). In addition, activities and recommendations throughout the public health assessment process may require input and support from other NCEH/ATSDR offices or divisions, such as the Office of Communication, Division of Health Education and Promotion, the Division of Health Studies, and the Division of Toxicology. For some sites, ATSDR's Washington, D.C. office may need to be involved or kept informed. For ATSDR partners, many of the tasks often undertaken by separate divisions within ATSDR will be conducted by the health assessor and local team members.

Figure 2-1 illustrates the individuals and groups that may play a role in the public health assessment process.

2.4 What Is the Role of the Site Community?

Communities often play an important role in the public health assessment process. For a particular site, the community generally consists of people who live and work at or around the site. The community may include, for example, residents, site or facility personnel, members of local action groups, local officials, tribal members, health professionals, and local media.

Community members are a resource for and a primary audience and beneficiaries of the public health assessment process. They can provide important information and ideas that may prove valuable input to the public health assessment. For example, they can often supply site-specific information that might otherwise not be documented. As you conduct your assessment, community members may also want to know what the process involves, what they can and cannot expect, what conclusions you reach, and in general how ATSDR and the public health assessment process can help address their concerns. The relationship you build with the community through your public involvement and communication activities will influence how much community members trust you and thus, ultimately, how they react to your public health messages and recommendations. For all these reasons, effective involvement of and communication with the community is important throughout the public health assessment process.

Since 1990, ATSDR has embraced the philosophy of continuous improvement of and increased attention to its community involvement and health education efforts, which include identifying and reaching out to the concerned public; informing and educating; promoting interaction and dialogue; involving communities in planning, implementing, and decision-making; providing opportunity for comments and input; and collaborating in developing meaningful partnerships.

Chapter 4 provides guidance on how to plan for and conduct community involvement activities. By reading Chapter 4 before the subsequent chapters, which provide guidance on the technical aspects of the public health assessment process, you will be better able to incorporate public involvement and basic communication principles into all the activities you perform at a site.

2.5 How Is a Public Health Assessment Conducted?

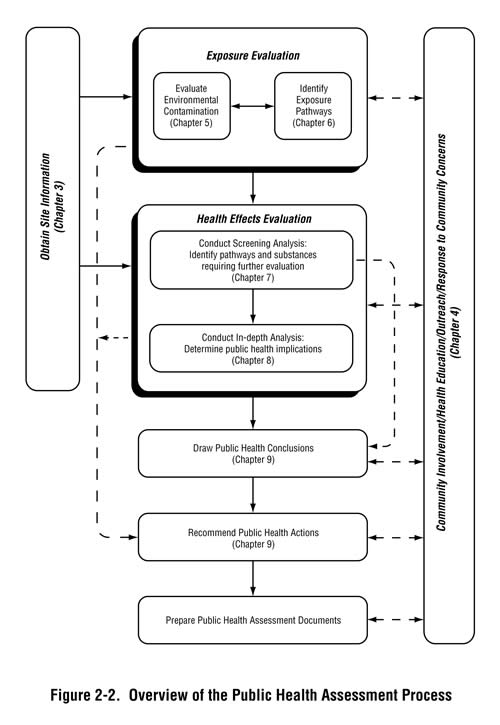

The public health assessment process involves multiple steps, but consists of two primary technical components—the exposure evaluation and the health effects evaluation. These two components lead to making conclusions and recommendations and identifying specific and appropriate public health actions to prevent harmful exposures.

Integral to the entire process are effective fact finding and thorough scientific evaluation. Identifying and understanding the public health concerns of the site community—as well as involving and effectively communicating with the public—is another important component of the process. Good communication among ATSDR, other agencies, and the community is essential throughout the public health assessment process.

The exposure evaluation involves studying the environmental data and understanding if and under what conditions people might contact contaminated media (e.g., water, soil, air, food chain [biota]). The information compiled in the exposure evaluation is used to support the health effects evaluation, which includes a screening component, a more detailed analysis of site-specific exposure considerations and of the substance-specific information obtained from the toxicologic and epidemiologic literature. An additional consideration, although not always available, is an evaluation of health outcome data for the community of interest.

The specific steps in the process are summarized below and detailed in Chapters 3 through 9. Figure 2-2 maps out the overall public health assessment process.

The evaluation is an iterative, dynamic process that considers available data from varying perspectives. The process is not always linear. In reality, many activities may occur simultaneously and/or require repeated efforts. Further, because sites are different, not every aspect of the public health assessment process described in this manual will apply to all sites.

Another very important point to remember about the process is that public health assessment teams should not wait to complete the entire step-by-step assessment process before recommending an action to address a public health hazard. Instead, the team should immediately focus its efforts on the public health hazard, confer with all stakeholders, and coordinate and implement appropriate actions to minimize exposures and protect public health.

The public health assessment process often requires the consideration of multiple data sets. It is the health assessor's job to sort through this information and identify key information that will help determine whether people are being exposed to site-related contaminants at sufficient levels to result in adverse health effects. As you do so, you should identify data gaps and limitations, such as the need for further environmental sampling.

Once assigned a site to evaluate, your first step is to establish an overall understanding of the site and begin to identify the most pertinent issues. You need to quickly gain some baseline information about your site. Once you start to build an information base, you can start developing a strategy for conducting the public health assessment.

To help ensure a consistent approach across sites, the following steps should be followed:

- Initiate site scoping. Perform an initial review of site files and general sources of site information (e.g., summary reports, petition letters, media reports, EPA summaries on the Web). Identify any past ATSDR activities or activities conducted by ATSDR's partners. The ATSDR regional staff are an important contact for site information at this initial step. Initial scoping efforts will help you identify the type of environmental, exposure, and community health concern information you may need to pursue. Identify and communicate with site contacts (e.g., state agencies, tribal governments, facility representatives) to learn about site environmental conditions, the status of site investigations, and the involvement of other stakeholders. During site scoping you will also determine when to conduct the site visit. The site visit should be viewed as a prime opportunity for meeting with the local community and gathering pertinent site information, in addition to providing you with first-hand knowledge of current site conditions.

- Define roles and responsibilities of team members (internal and external). Identify core team members as early as possible. As described in Section 2.3, the mix of the team and each member's responsibility will depend on site issues. Establishing the team early will foster better communications throughout the public health assessment process.

- Establish communication mechanisms (internal and external). Establish government agency, tribal, site, community, and other stakeholder contacts early in the process. Develop a schedule for team meetings, start considering how to present the findings of your assessment, and develop health communication strategies. This requires understanding the information needs of your audience. Adequate communication with the local community is an important part of the public health assessment process. Therefore, a strategy to develop and maintain communication with the community should be developed early in the process.

- Develop a site strategy. As you move forward, be mindful of the various steps in the public health assessment process (see Figure 2-2) and develop a strategy for completing these tasks. Each of these steps are summarized in the sections below and detailed in subsequent chapters of this manual. During the planning stages, you will need to begin to identify the tools and resources that might be needed to evaluate the site, communicate your findings, and implement public health actions. Careful planning will provide a strong foundation for all subsequent activities.

Based on information obtained during site scoping, develop an approach that focuses on the most pertinent public health issues. Identify site priorities both in terms of potential exposures and community health concerns. Establish aggressive but realistic time lines for the various components of your site-specific evaluation. Note that your strategy may change over time. Remember that the public health assessment process is iterative. The information you gain as you conduct your public health assessment may generate new information and perspectives that may prompt you to revise your strategy.

2.5.2 Collecting Needed Information

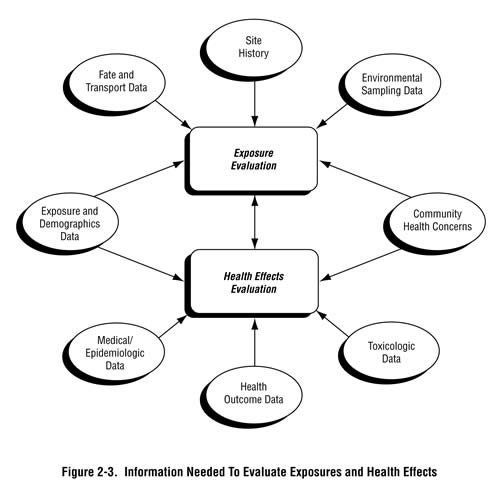

Throughout the public health assessment process, you and other site team members will collect information about the site. Figure 2-3 illustrates the type of information that supports the assessment.

Information gathering generally occurs throughout the public health assessment process, but the initial collection of information is typically the most intensive. In the early phases of information collection, described in detail in Chapter 3, you are building the foundation of site-specific information and data for the rest of your activities at the site. As mentioned above, you will be collecting information about community health concerns, exposure pathways, and environmental contamination, as well as identifying any site-specific health outcome data. Information sources typically include interviews (in-person or via telephone); site-specific investigation reports prepared by EPA, other federal agencies, and state, tribal, and local environmental and health departments; and site visits.

Gathering pertinent site information requires a series of iterative steps, including gaining a basic understanding of the site, identifying data needs and sources, conducting a site visit, communicating with community members and other stakeholders, critically reviewing site documentation, identifying data gaps, and compiling and organizing relevant data to support the assessment.

2.5.3 Exposure Evaluation: Evaluating Environmental Contamination Data

Critical to the public health assessment process is evaluating exposures. One component of this evaluation is understanding the nature and extent of environmental contamination at and around a site. During this step, described in detail in Chapter 5, you will evaluate the environmental contamination data obtained to determine what contaminants people may be exposed to and in what concentrations. As part of this evaluation, you will be assessing the quality and representativeness of available environmental monitoring data and determining exposure point concentrations. This is an important way to ensure that any public health conclusions and recommendations for the site are based on appropriate and reliable data. In some cases, further environmental sampling may be recommended to fill a critical data gap. While sampling data are preferred for public health assessments, mathematical modeling techniques are sometimes used to estimate environmental concentrations either temporally or spatially (see Section 5.2). Evaluation of environmental contamination data typically proceeds simultaneously with the exposure pathway evaluation.

2.5.4 Exposure Evaluation: Identifying Exposure Pathways

During the exposure pathway evaluation, described in detail in Chapter 6, you will evaluate who may be or has been exposed to site contaminants, for how long, and under what conditions. You will consider past, current, and potential future exposure conditions. This involves identifying and studying the following five components of a "completed" exposure pathway:

- A source of contamination.

- A release mechanism into water, soil, air, food chain (biota) or transfer between media (i.e., the fate and transport of environmental contamination).

- An exposure point or area (e.g., drinking water well, residential yard).

- An exposure route (e.g., ingestion, dermal contact, inhalation).

- A potentially exposed population (e.g., residents, children, workers).

The overall purpose of this evaluation is to understand how people might become exposed to site contaminants (e.g., via drinking affected water or by coming in contact with contaminated soils) and to identify and characterize the size and susceptibility of the potentially exposed populations. If all of the elements described above are identified, a completed pathway exists. If one or more components are missing or uncertain, a potential exposure pathway may exist. For completed or potential exposure pathways, you will evaluate the magnitude, frequency, and duration of exposures.

As you evaluate exposure pathways, you should constantly remind yourself: If no completed or potentially completed exposure pathways are identified, no public health hazards will exist. If, as a result of your evaluation, you conclude there are no exposure pathways, then you will not need to perform further scientific evaluation. You will, however, need to explain your rationale for excluding each exposure pathway you deem incomplete and should communicate the conclusion of an incomplete pathway to the public at the earliest point possible. Additional community concerns not related to potential exposure pathways may be addressed in the community concerns section of the written public health assessment or the public health action plan (see Section 2.7).

When complete environmental or biologic data are lacking for a site, you may determine that an exposure investigation is needed to better assess possible impacts to public health. These exposure investigations, often conducted by ATSDR or cooperative agreement partners, may include environmental sampling, measurements of current human exposure (e.g., biologic monitoring), and/or using a variety of fate and transport models linked with geographic information systems to estimate past (dose reconstruction) or predict future exposure concentrations. The results of an exposure investigation are used to support the public health assessment process.

2.5.5 Health Effects Evaluation: Conducting Screening Analyses

Screening is a first step in understanding whether the detected concentrations to which people may be exposed are harmful. The screening analysis, described in detail in Chapter 7, is a fairly standard process ATSDR has developed to help health assessors sort through the often large volumes of environmental data for a site. It enables you to safely rule out substances that are not at levels of health concern and to identify substances and pathways that need to be examined more closely. For completed or potential exposure pathways identified in the exposure pathway evaluation, the screening analysis may involve:

- Comparing media concentrations at points of exposure to health-based "screening" values (based on protective default exposure assumptions).

- Estimating exposure doses based on site-specific exposure conditions that you will then compare with health-based guidelines.

2.5.6 Health Effects Evaluation: Conducting In-Depth Analyses

For those pathways and substances that you identify in the screening analysis as requiring more careful consideration, you and site team members will examine a host of factors to help determine whether site-specific exposures are likely to result in illness and whether a public health response is needed. In this integrated approach, described in detail in Chapter 8, exposures are studied in conjunction with substance-specific toxicologic, medical, and epidemiologic data.

Through this in-depth analysis, you will be answering the following question: Based on available exposure, toxicologic, epidemiologic, medical, and site-specific health outcome data, are adverse health effects likely in the community? You will be considering not only the potential health impacts on the general community, but also the impact of site-specific exposures to any uniquely vulnerable populations (e.g., children, the elderly, women of child-bearing age, fetuses, and lactating mothers) in the community.

2.5.7 Formulating Conclusions and Recommendations and Developing a Public Health Action Plan

Upon completing the exposure and health effects evaluations, you will draw conclusions regarding the degree of hazard posed by a site (described in detail in Chapter 9)—that is, you will conclude either that the site does not pose a public health hazard, that the site poses a public health hazard, or that insufficient data are available to determine whether any public health hazards exist. The process also involves assigning a "hazard conclusion category" for the site or for an individual exposure pathway. After drawing conclusions (which occurs throughout the public health assessment process), you will develop recommendations for actions, if any, to prevent harmful exposures, obtain more information, or conduct other public health actions. These actions will be detailed in a Public Health Action Plan, which will ultimately be part of the public health assessment document (or possibly public health consultations) you develop for the site, as described in Section 2.6. Note that some public health actions may be recommended earlier in the process (see Section 2.6).

2.6 What Products and Actions Result From the Public Health Assessment Process?

You may develop various materials during the public health assessment process to communicate information about the assessment. For example, the team may develop outreach materials, as described in Chapter 4 , to communicate the status and findings of your assessment to the site community. If you identify imminent health hazards during the assessment process, you may issue a health advisory that alerts the public and appropriate officials to the existence of a public health threat and identifies measures/actions that should be taken immediately to eliminate the health threat (see Chapter 9 for more information about health advisories). Whether and when to produce these materials or advisories and in what format is up to the judgment of the site team and their management.

At the end of the assessment process, you will prepare a report that summarizes your approach, results, conclusions, and recommendations. This report may be either a public health assessment document (PHA) or a public health consultation (PHC).

- A PHA may be prepared to address various exposure situations and/or community health concerns. It may address multiple-chemical, multiple-pathway exposures or it may address a single exposure pathway. Regardless of the focus of the PHA, all of the CERCLA-required elements must be included in the PHA.

- A PHC is generally prepared to describe the findings of an assessment that focuses on one particular public health question (e.g., a specific exposure pathway, substance, health condition, or technical interpretation). For example: Will community members be harmed by drinking water from private wells around the site? Is a proposed site-specific sampling plan adequate to collect data to use in a public health evaluation? Such assessments often are more time critical, necessitating a more rapid and therefore limited response than assessments that result in a PHA. While some PHCs include a presentation of all the elements required in the PHA (i.e., a comprehensive exposure pathway and health effects evaluation), discussions are often limited to answering the question at hand.

A PHA is generally produced for all NPL sites. For petitioned sites, you may produce either a PHA or a PHC depending on site-specific issues and information needs. Sometimes, an assessment of a single issue at a petitioned site may evolve into a more multifaceted assessment that results in a PHA. Regardless of the document prepared, the overall assessment process, as described in this manual, is generally the same.

As stated earlier, during the public health assessment process, you will not only evaluate whether a site poses a public health hazard, but also identify public health actions. Actions may be recommended at any appropriate point in the assessment process. Some recommended actions may be initiated before the completion of the PHA, such as certain health education activities or efforts to obtain additional exposure data. Other actions may begin during the assessment process but end after the release of the PHA for a site (e.g., health studies or research). Community involvement continues to be important as you identify and communicate public health actions.

Public health actions vary from site to site and may include:

- Actions to reduce exposures. If current harmful exposures are identified, removal or clean-up actions may be recommended. This will generally involve working with the appropriate federal, state, or tribal agencies.

- Exposure investigations. As part of your exposure evaluation, you may determine that critical exposure data are missing. In such cases, the site team may recommend environmental or biologic sampling to better define the extent, if any, of harmful exposures. (see Section 6.7)

- Health education. Throughout the public health assessment process, you may identify the need for education within a community. For example, ATSDR's Division of Health Education and Promotion or the appropriate local health department may educate health professionals about special diagnostic techniques for possible site-related illnesses identified during the public health assessment process.

- Health services. Site conditions may identify the need for certain community health interventions, such as medical monitoring or psychological stress counseling. Referrals may be made to health care providers (e.g., community health centers or local health departments) when health services are needed that may improve the overall health of the community. ATSDR does not have the legal authority to provide medical care or treatment to people who have been exposed to hazardous substances, even if the exposure has made them ill. ATSDR works with health care agencies to address community health care needs.

- Health studies/health surveillance. Public health assessments are not epidemiologic or health studies. However, during the public health assessment process, you may identify an exposed population for whom a site-specific epidemiologic or health study should be considered (e.g., disease- and symptom-prevalence studies, cluster investigations). An epidemiologist should be involved with evaluating the need and feasibility of any such study. ATSDR's Division of Health Studies or comparable local agency should be involved in designing, implementing, and interpreting any such study.

- Research. Knowledge gaps that you identify concerning the toxicity of substances identified at a site or release under review may trigger substance-specific research, computational toxicology, or expanded efforts in developing ATSDR toxicological profiles.

General PHA Format

- Primary sections

- Summary

- Purpose and health issues

- Background

- Discussion 1

- Community health concerns

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Public health action plan

- Preparers of report

- References

- Tables

- Figures

- Appendices

- Additional background materials

- More in-depth technical discussions

- Glossary (including conclusion category summary)

- Response to public comments

_____________

1A separate discussion on child health considerations is required in all PHAs.

2.7 What Is the Format for Public Health Assessment Documents?

This section describes the content and format guidelines for PHAs and PHCs. Communicating the findings of your assessment in an organized, clear, and concise way is equal in importance to conducting a scientifically sound evaluation. As you prepare a public health assessment document, you will make many choices about how to organize material within each section, how much detail to provide, whether to use a question-and-answer format in various sections, and so on.

While ATSDR has developed the minimum requirements presented below to ensure consistency and completeness, the agency encourages health assessors to remain flexible while fulfilling these requirements. You should use the most appropriate site-specific approach, based on the knowledge, expectations, and information needs of your audience. The suggested format provides a framework for documenting the findings of the public health assessment. Subsequent chapters provide more detail on the type of information that you may need to consider and include in each section of the document.

Generally, PHAs include the sections and appendices described below. Additional sections may be included as you judge appropriate if the information may be helpful in communicating the findings. The main body of the document should be long enough to fully address pertinent issues. Narratives should be concise and relevant to those issues.

The primary sections of a PHA are:

- Summary. In this section, you will summarize the most important conclusions and recommendations of the PHA. This section should be as simple, clear, and concise as possible, since it will be one of the most frequently read sections of the document. As appropriate, you may include a brief summary of previous public health evaluations of the site and/or a brief explanation of the planned future public health evaluations of the site. Do not include any technical information, conclusions, or recommendations that are not addressed in the main body of the document.

- Purpose and Health Issues. In this section, you should explain what the PHA will and will not discuss. This section focuses the discussion for the rest of the PHA by posing the question(s) that will be addressed in the PHA. This section may include a brief overview of the health concerns voiced by the site community, with reference to a later section in the PHA that addresses those concerns.

- Background. This section should contain all pertinent "factual" information and data needed to frame or lead into the Discussion section. Typically in this section, you will present the site description, site history, demographics, land use, and natural resource use as it relates to the issues presented in the Purpose and Health Issues section. Do not include any information not directly relevant to the issue(s) being discussed in the PHA (though you may place it in an appendix if you judge it important to make the information available to the reader).

- Discussion. In this section, report the findings of your exposure and health effects evaluations. Describe what is known (and not known) about environmental exposures to site-specific contaminants. Clearly describe site-specific exposure conditions (or how people may contact site contaminants). Then discuss how site-specific exposure levels compare with health-based screening levels; if screening levels are exceeded, then explain how site-specific exposure levels (and conditions) compare to levels shown to cause harm in relevant scientific studies. Describe how the integration of pertinent exposure and health effects data leads you to your overall conclusion—that is, explain/state whether site-specific conditions are likely to result in adverse health effects. This discussion should provide support for and help to justify the conclusions that you will present in the subsequent Conclusions section. You must also include a distinct subsection within the Discussion section that discusses child health issues. You can use different formats for the Discussion section depending on the site. In some cases, you may wish to discuss public health issues on an exposure pathway-by-pathway basis. In others, a question-and-answer format might work better. You may provide varying levels of technical detail as appropriate to the site, but, you should always strive to keep the text clear and simple and use appendices as appropriate to provide more detailed technical discussions. Also, you should use tables, figures, and maps whenever possible to facilitate the understanding of written text.

- Community Health Concerns. In this section, present answers to any health questions the public may have about the site. A question-and-answer format is often most appropriate. You can include the Community Health Concerns section either as a separate section in the PHA or as a subsection of the Discussion section, depending on which is most appropriate to the optimal logic and flow of the document.

- Conclusions. In this section, briefly present the conclusions of the public health assessment process. If you have reached more than one conclusion, you may want to present your conclusions as a list, starting with the conclusion(s) that directly address the issues presented in the Purpose and Health Issues section. Include a statement that assigns a hazard conclusion category (see Section 2.5.7 and Chapter 9) to the site, time period (e.g., past, current, or future), or exposure pathway, as appropriate. While you should not reiterate large portions of previous sections, you must support each conclusion with a brief but adequate discussion of available data and information. This summation should follow logically from the relevant portions of the Discussion section.

- Recommendations. In this section, you will describe recommendations that the site team has developed based on the conclusions reached about the site, as described in the Conclusions section. Generally, the most effective way to communicate recommendations is to organize them as a list and to begin each recommendation with an action word (e.g., provide, monitor, restrict, obtain, inform, etc.). Again, ATSDR makes public health recommendations; it does not make specific risk management decisions. Ideally, communication among ATSDR and parties responsible for implementing the recommendations will have been ongoing throughout the public health assessment process. Such communication will help identify actions needed to implement the recommendations.

- Public Health Action Plan. Every PHA must include a public health action plan (PHAP) indicating the specific actions that are warranted. The PHAP should present actions that have been completed as well as those that are ongoing or planned. Discussion with the entities (e.g., other agencies) who will ultimately be responsible for conducting specific actions is required ahead of time.

In addition to the main text of the document you must include the preparers of the report, references, and various appendices. While your text should be written as clearly and concisely as possible when relaying the findings of the assessment, the use of various technical terms will likely be unavoidable. You should, therefore, include a glossary of terms in all PHAs. The "plain language" glossary developed by ATSDR should be used as a starting point (see Appendix B). As mentioned, you will need to assign a conclusion category to your site and the exposure situations evaluated. A summary of the five ATSDR conclusion categories must be included in all PHAs, either as part of your glossary or as a stand-alone list.

For the final version of the PHA, you will have gathered public comments. An appendix will be dedicated to listing these comments and explain how the PHA responds them. The format and content of the appendix will depend on the number and nature of the comments you have received; the responses will be based on the judgment of the site team. For example, if comments are few in number or represent unique issues, you will likely present each comment more or less verbatim. In other cases, you may choose to summarize like comments or edit comments to more succinctly present expressed concerns or questions. When doing so, be careful not to eliminate specific points made or question asked by the commenters. To facilitate your response and present it effectively, group comments by major theme or by section of the PHA (e.g., site history, groundwater issues, conclusions). In your responses, focus on addressing technical issues raised by commenters, explaining how and why ATSDR took a certain approach or drew a particular conclusion. If the comment points out an error or introduces new information, acknowledge any error, review any new data, and explain how ATSDR may have revised its assessment in light of that information. (Section 4.7.1.3 in Chapter 4 provides additional guidance in responding to public comments.)

Like the PHA, the PHC has certain minimum requirements as set forth by agency policy (May 27, 1995). The PHC should include, at a minimum, the following:

- Summary(1)

- Background/Statement of Issues

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- PHAP, if applicable

- Response to Public Comments, if applicable

- References

- Appendices (as required)

In preparing PHAs and PHCs, your text should be written in as clear and understandable a way as possible. The box below contains a few tips for effective communication. Many of these tips are elaborated upon in subsequent chapters.

Communication Tips for Preparing PHAs and PHCs

- Tell the story.

- Consider your audience(s).

- Be concise (do not include anything that does not add to the story).

- Use "plain" language where possible to describe the evaluation and conclusions.

- Use the active voice.

- Clearly communicate the following concepts:

- Public health assessments are exposure-driven. Remember, exposure must occur to allow the potential for adverse health effects.

- Simply being exposed to a hazardous substance does not make it a hazard—the magnitude, frequency, timing of exposure (e.g. pregnant female, fetal development), duration of the exposure, and the toxicity characteristics of individual substances affect the degree of hazard, if any.

- Think perspective. Put available environmental and health effects data into meaningful perspective for the community.

- The language should not unnecessarily alarm the reader, nor should the health assessor downplay concerns/exposures.

- Write a simple summary that will capture key points and give bottom lines.

- Keep conclusions focused and be sure that recommendations parallel the conclusions.

- If information is unavailable and, as a result, no conclusions can be drawn, simply state this fact.

- Reference all statements of fact—make it clear what are judgments and opinions.

1A summary is optional in a PHC, but recommended when the PHC is lengthy or technically complex.

- Page last reviewed: November 30, 2005

- Page last updated: November 30, 2005

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir