Research on meditation

For the purpose of this article, research on meditation concerns research into the psychological and physiological effects of meditation using the scientific method. In recent years, these studies have increasingly involved the use of modern scientific techniques and instruments, such as fMRI and EEG which are able to directly observe brain physiology and neural activity in living subjects, either during the act of meditation itself, or before and after a meditation effort, thus allowing linkages to be established between meditative practice and changes in brain structure or function.

Since the 1950s hundreds of studies on meditation have been conducted, but many of the early studies were flawed and thus yielded unreliable results.[1][2] Contemporary studies have attempted to address many of these flaws with the hope of guiding current research into a more fruitful path.[3] In 2013, researchers at Johns Hopkins, publishing in the Journal of the American Medical Association, identified 47 studies that qualify as well-designed and therefore reliable. Based on these studies, they concluded that there is moderate evidence that meditation reduces anxiety, depression, and pain, but no evidence that meditation is more effective than active treatment (drugs, exercise, other behavioral therapies).[4] A 2017 commentary was similarly mixed.[5][6]

The process of meditation, as well as its effects, is a growing subfield of neurological research.[7][8] Modern scientific techniques and instruments, such as fMRI and EEG, have been used to study how regular meditation affects individuals by measuring brain and bodily changes.[7]

Difficulties in the scientific study of meditation

Weaknesses in historic meditation and mindfulness research

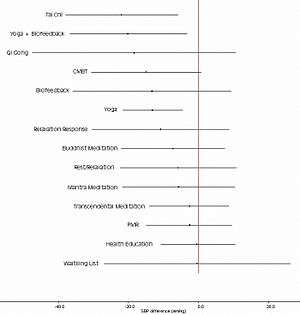

In June, 2007 the United States National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) published an independent, peer-reviewed, meta-analysis of the state of meditation research, conducted by researchers at the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center. The report reviewed 813 studies involving five broad categories of meditation: mantra meditation, mindfulness meditation, yoga, T'ai chi, and Qigong, and included all studies on adults through September 2005, with a particular focus on research pertaining to hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and substance abuse. The report concluded, "Scientific research on meditation practices does not appear to have a common theoretical perspective and is characterized by poor methodological quality. Future research on meditation practices must be more rigorous in the design and execution of studies and in the analysis and reporting of results." (p. 6) It noted that there is no theoretical explanation of health effects from meditation common to all meditation techniques.[1]

A version of this report subsequently published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine stated that "Most clinical trials on meditation practices are generally characterized by poor methodological quality with significant threats to validity in every major quality domain assessed". This was the conclusion despite a statistically significant increase in quality of all reviewed meditation research, in general, over time between 1956 and 2005. Of the 400 clinical studies, 10% were found to be good quality. A call was made for rigorous study of meditation.[3] These authors also noted that this finding is not unique to the area of meditation research and that the quality of reporting is a frequent problem in other areas of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) research and related therapy research domains.

Of more than 3,000 scientific studies that were found in a comprehensive search of 17 relevant databases, only about 4% had randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which are designed to exclude the placebo effect.[1]

In a 2013 meta-analysis, Awasthi argued that meditation is defined poorly and despite the research studies showing clinical efficacy, exact mechanisms of action remain unclear.[9] A 2017 commentary was similarly mixed,[5][6] with concerns including the particular characteristics of individuals who tend to participate in mindfulness and meditation research.[10]

Position statements

A 2013 statement from the American Heart Association (AHA) evaluated the evidence for the effectiveness of TM as a treatment for hypertension as "unknown/unclear/uncertain or not well-established", and stated: "Because of many negative studies or mixed results and a paucity of available trials... other meditation techniques are not recommended in clinical practice to lower BP at this time."[11] According to the AHA, while there are promising results about the impact of meditation in reducing blood pressure and managing insomnia, depression and anxiety, it is not a replacement for healthy lifestyle changes and is no substitute for effective medication.[12]

Methodological obstacles

The term meditation encompasses a wide range of practices and interventions rooted in different traditions, but research literature has sometimes failed to adequately specify the nature of the particular meditation practice(s) being studied.[13] Different forms of meditation pratice may yield different results depending on the factors being studied.[13]

The presence of a number of intertwined factors including the effects of meditation, the theoretical orientation of how meditation practices are taught, the cultural background of meditators, and generic group effects complicates the task of isolating the effects of meditation:[14]

Numerous studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of a variety of meditation practices. It has been unclear to what extent these practices share neural correlates. Interestingly, a recent study compared electroencephalogram activity during a focused-attention and open monitoring meditation practice from practitioners of two Buddhist traditions. The researchers found that the differences between the two meditation traditions were more pronounced than the differences between the two types of meditation. These data are consistent with our findings that theoretical orientation of how a practice is taught strongly influences neural activity during these practices. However, the study used long-term practitioners from different cultures, which may have confounded the results.

Research on mindfulness

A previous study commissioned by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found that meditation interventions reduce multiple negative dimensions of psychological stress.[4] Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that mindfulness meditation has several mental health benefits such as bringing about reductions in depression symptoms,[15][16][17] and mindfulness interventions also appear to be a promising intervention for managing depression in youth.[18][19] Mindfulness meditation is useful for managing stress,[16][20][21] anxiety,[15][16][21] and also appears to be effective in treating substance use disorders.[22][23][24] A recent meta analysis by Hilton et al. (2016) including 30 randomized controlled trials found high quality evidence for improvement in depressive symptoms.[25] Other review studies have shown that mindfulness meditation can enhance the psychological functioning of breast cancer survivors,[16] is effective for people with eating disorders,[26][27] and may also be effective in treating psychosis.[28][29][30]

Studies have also shown that rumination and worry contribute to mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety,[31] and mindfulness-based interventions are effective in the reduction of worry.[31][32]

Some studies suggest that mindfulness meditation contributes to a more coherent and healthy sense of self and identity, when considering aspects such as sense of responsibility, authenticity, compassion, self-acceptance and character.[33][34]

Brain mechanisms

In 2011, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) released findings from a study in which magnetic resonance images were taken of the brains of 16 participants 2 weeks before and after the participants joined the mindfulness meditation (MM) program by researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital, Bender Institute of Neuroimaging in Germany, and the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Researchers concluded that

..these findings may represent an underlying brain mechanism associated with mindfulness-based improvements in mental health.[35]

The analgesic effect of MM involves multiple brain mechanisms including the activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.[36] In addition, brief periods of MM training increases the amount of grey matter in the hippocampus and parietal lobe.[37] Other neural changes resulting from MM may increase the efficiency of attentional control.[38]

Participation in MBSR programmes has been found to correlate with decreases in right basolateral amygdala gray matter density,[39] and increases in gray matter concentration within the left hippocampus.[40]

Changes in the brain

Mindfulness meditation also appears to bring about favorable structural changes in the brain, though more research needs to be done because most of these studies are small and have weak methodology.[41] One recent study found a significant cortical thickness increase in individuals who underwent a brief -8 weeks- MBSR training program and that this increase was coupled with a significant reduction of several psychological indices related to worry, state anxiety, depression.[42] Another study describes how mindfulness based interventions target neurocognitive mechanisms of addiction at the attention-appraisal-emotion interface.[23] A meta-analysis by Fox et al. (2014) using results from 21 brain imaging studies found consistent differences in the region of the prefrontal cortex and other brain regions associated with body awareness. In terms of effect size the mean effect was rated as moderate. (Cohen's d = 0.46) However the results should be interpreted with caution because funnel plots indicate that publication bias is an issue in meditation research.[41] A follow up by Fox et al. (2016) using 78 functional neuro-imaging studies suggests that different meditation styles are reliably associated with different brain activity. Activations in some brain regions are usually accompanied by deactivation in others. This finding suggests that meditation research must put emphasis on comparing practices from the same style of meditation, for example results from studies investigating focused attention methods cannot be compared to results from open monitoring approaches.[43]

Attention and mindfulness

Attention networks and mindfulness meditation

Psychological and Buddhist conceptualisations of mindfulness both highlight awareness and attention training as key components, in which levels of mindfulness can be cultivated with practise of mindfulness meditation.[44] Focused attention meditation (FAM) and open monitoring meditation (OMM) are distinct types of mindfulness meditation; FAM refers to the practice of intently maintaining focus on one object, whereas OMM is the progression of general awareness of one's surroundings while regulating thoughts.[45][46]

Focused attention meditation is typically practiced first to increase the ability to enhance attentional stability, and awareness of mental states with the goal being to transition to open monitoring meditation practise that emphasizes the ability to monitor moment-by-moment changes in experience, without a focus of attention to maintain. Mindfulness meditation may lead to greater cognitive flexibility.[47]

Evidence for improvements in three areas of attention

Sustained attention

- Tasks of sustained attention relate to vigilance and the preparedness that aids completing a particular task goal. Psychological research into the relationship between mindfulness meditation and the sustained attention network have revealed the following:

- Mindfulness meditators have demonstrated superior performance when the stimulus to be detected in a task was unexpected, relative to when it was expected. This suggests that attention resources were more readily available in order to perform well in the task. This was despite not receiving a visual cue to aid performance. (Valentine & Sweet, 1999).

- In a continuous performance task[48] an association was found between higher dispositional mindfulness and more stable maintenance of sustained attention.

- In an EEG study, the Attentional blink effect was reduced, and P3b ERP amplitude decreased in a group of participants who completed a mindfulness retreat.[49] The incidence of reduced attentional blink effect relates to an increase in detectability of a second target. This may have been due to a greater ability to allocate attentional resources for detecting the second target, reflected in a reduced P3b amplitude.

- A greater degree of attentional resources may also be reflected in faster response times in task performance, as was found for participants with higher levels of mindfulness experience.[50]

Selective attention

- Selective attention as linked with the orientation network, is involved in selecting the relevant stimuli to attend to.

- Performance in the ability to limit attention to potentially sensory inputs (i.e. selective attention) was found to be higher following the completion of an 8-week MBSR course, compared to a one-month retreat and control group (with no mindfulness training).[50] The ANT task is a general applicable task designed to test the three attention networks, in which participants are required to determine the direction of a central arrow on a computer screen.[51] Efficiency in orienting that represent the capacity to selectively attend to stimuli was calculated by examining changes in the reaction time that accompanied cues indicating where the target occurred relative to the aid of no cues.

- Meditation experience was found to correlate negatively with reaction times on an Eriksen flanker task measuring responses to global and local figures. Similar findings have been observed for correlations between mindfulness experience in an orienting score of response times taken from Attention Network Task performance.[52]

- Participants who engaged in the Meditation Breath Attention Score exercise performed better on anagram tasks and reported greater focused attention on this task compared to those who did not undergo this exercise.[53]

Executive control attention

- Executive control attention include functions of inhibiting the conscious processing of distracting information. In the context of mindful meditation, distracting information relates to attention grabbing mental events such as thoughts related to the future or past.[46]

- More than one study have reported findings of a reduced Stroop effect following mindfulness meditation training.[47][54][55] The Stroop effect indexes interference created by having words printed in colour that differ to the read semantic meaning e.g. green printed in red. However findings for this task are not consistently found.[56][57] For instance the MBSR may differ to how mindful one becomes relative to a person who is already high in trait mindfulness.[38]

- Using the Attention Network Task (a version of Eriksen flanker task [51]) it was found that error scores that indicate executive control performance were reduced in experienced meditators [50] and following a brief 5 session mindfulness training program.[54]

- A neuroimaging study supports behavioural research findings that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with greater proficiency to inhibit distracting information. As greater activation of the rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) was shown for mindfulness meditators than matched controls.

- Participants with at least 6 years of experience meditating performed better on the Stroop Test compared to participants who had not had experience meditating.[58] The group of meditators also had lower reaction times during this test than the group of non-meditators.[58]

- Following a Stroop test, reduced amplitude of the P3 ERP component was found for a meditation group relative to control participants. This was taken to signify that mindfulness meditation improves executive control functions of attention. An increased amplitude in the N2 ERP component was also observed in the mindfulness meditation group, thought to reflect more efficient perceptual discrimination in earlier stages of perceptual processing.[59]

Emotion regulation and mindfulness

Research shows meditation practices lead to greater emotional regulation abilities. Mindfulness can help people become more aware of thoughts in the present moment, and this increased self-awareness leads to better processing and control over one's responses to surroundings or circumstances.[60][61]

Positive effects of this heightened awareness include a greater sense of empathy for others, an increase in positive patterns of thinking, and a reduction in anxiety.[61][60] Reductions in rumination also have been found following mindfulness meditation practice, contributing to the development of positive thinking and emotional well-being.

Evidence of mindfulness and emotion regulation outcomes

Emotional reactivity can be measured and reflected in brain regions related to the production of emotions.[62] It can also be reflected in tests of attentional performance, indexed in poorer performance in attention related tasks. The regulation of emotional reactivity as initiated by attentional control capacities can be taxing to performance, as attentional resources are limited.[63]

- Patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD) exhibited reduced amygdala activation in response to negative self-beliefs following an MBSR intervention program that involves mindfulness meditation practice.[64]

- The LPP ERP component indexes arousal and is larger in amplitude for emotionally salient stimuli relative to neutral.[65][66][67] Individuals higher in trait mindfulness showed lower LPP responses to high arousal unpleasant images. These findings suggest that individuals with higher trait mindfulness were better able to regulate emotional reactivity to emotionally evocative stimuli.[68]

- Participants who completed a 7-week mindfulness training program demonstrated a reduction in a measure of emotional interference (measured as slower responses times following the presentation of emotional relative to neutral pictures). This suggests a reduction in emotional interference.[69]

- Following a MBSR intervention, decreases in social anxiety symptom severity were found, as well as increases in bilateral parietal cortex neural correlates. This is thought to reflect the increased employment of inhibitory attentional control capacities to regulate emotions.[70][71]

- Participants who engaged in emotion-focus meditation and breathing meditation exhibited delayed emotional response to negatively valanced film stimuli compared to participants who did not engage in any type of meditation.[72]

Controversies in mindful emotion regulation

It is debated as to whether top-down executive control regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC),[73] are required[71] or not[64] to inhibit reactivity of the amygdala activation related to the production of evoked emotional responses. Arguably an initial increase in activation of executive control regions developed during mindfulness training may lessen with increasing mindfulness expertise.[74]

Stress reduction

Research has shown stress reduction benefits from mindfulness.[75][76][77] A 2019 study tested the effects of meditation on the psychological well-being, work stress, and blood pressure of employees working in the United Kingdom. One group of participants were instructed to meditate once a day using a mindfulness app on their smartphones, while the control group did not engage in meditation. Measurements of well-being, stress, and perceived workplace support were taken for both groups before the intervention and then again after 4 months. Based on self-report questionnaires, the participants who engaged in meditation showed a significant increase in psychological well-being and perceived workplace support. The meditators also reported a significant decrease in anxiety and stress levels.[77]

Other research shows decreased stress levels in people who engage in meditation after shorter periods of time as well. Brief, daily meditation sessions can alter one's behavioral response to stressors, improving coping mechanisms and decreasing the adverse impact caused be stress.[78][79] A study from 2016 examined anxiety and emotional states of naive meditators before and after a 7-day meditation retreat in Thailand. Results displayed a significant reduction in perceived stress after this traditional Buddhist meditation retreat.[79]

Future directions

A large part of mindfulness research is dependent on technology. As new technology continues to be developed, new imaging techniques will become useful in this field. Real-time fMRI might give immediate feedback and guide participants through the programs. It could also be used to more easily train and evaluate mental states during meditation itself.[80] The new technology in the upcoming years offers many new opportunities for the continued research.

Research on other types of meditation

Insight (Vipassana) meditation

Vipassana meditation is a component of Buddhist practice. Phra Taweepong Inwongsakul and Sampath Kumar from the University of Mysore have been studying the effects of this meditation on 120 students by measuring the associated increase of cortical thickness in the brain. The results of this study are inconclusive.[81][82]

Sahaja yoga and mental silence

Sahaja yoga meditation is regarded as a mental silence meditation, and has been shown to correlate with particular brain[83][84] and brain wave[85][86][87] characteristics. One study has led to suggestions that Sahaja meditation involves 'switching off' irrelevant brain networks for the maintenance of focused internalized attention and inhibition of inappropriate information.[88] Sahaja meditators appear to benefit from lower depression[89] and scored above control group for emotional well-being and mental health measures on SF-36 ratings.[90][91][92]

A study comparing practitioners of Sahaja Yoga meditation with a group of non meditators doing a simple relaxation exercise, measured a drop in skin temperature in the meditators compared to a rise in skin temperature in the non meditators as they relaxed. The researchers noted that all other meditation studies that have observed skin temperature have recorded increases and none have recorded a decrease in skin temperature. This suggests that Sahaja Yoga meditation, being a mental silence approach, may differ both experientially and physiologically from simple relaxation.[87]

Kundalini yoga

Kundalini yoga has proved to increase the prevention of cognitive decline and evaluate the response of biomarkers to treatment, thereby shedding light on the underlying mechanisms of the link between Kundalini Yoga and cognitive impairment. For the study, 81 participants aged 55 and older who had subjective memory complaints and met criteria for mild cognitive impairment, indicated by a total score of 0.5 on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale. The results showed that at 12 weeks, both the yoga group showed significant improvements in recall memory and visual memory and showed significant sustained improvement in memory up to the 24-week follow-up, the yoga group showed significant improvement in verbal fluency and sustained significant improvements in executive functioning at week 24. In addition, the yoga cohort showed significant improvement in depressive symptoms, apathy, and resilience from emotional stress. This research was provided by Helen Lavretsky, M.D. and colleagues.[93] In another study, Kundalini Yoga did not show significant effectiveness in treating obsessive-compulsive disorders compared with Relaxation/Meditation.[94]

Transcendental Meditation

The first Transcendental Meditation (TM) research studies were conducted at UCLA and Harvard University and published in Science and the American Journal of Physiology in 1970 and 1971.[95] However, much research has been of poor quality,[1][94][96] including a high risk for bias due to the connection of researchers to the TM organization and the selection of subjects with a favorable opinion of TM.[97][98][99] Independent systematic reviews have not found health benefits for TM exceeding those of relaxation and health education.[1][94][98] A 2013 statement from the American Heart Association described the evidence supporting TM as a treatment for hypertension as Level IIB, meaning that TM "may be considered in clinical practice" but that its effectiveness is "unknown/unclear/uncertain or not well-established". In another study, TM proved comparable with other kinds of relaxation therapies in reducing anxiety.[94]

Research on unspecified or multiple types of meditation

Brain activity

The medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate cortices have been found to be relatively deactivated during meditation (experienced meditators using concentration, lovingkindness and choiceless awareness meditation). In addition experienced meditators were found to have stronger coupling between the posterior cingulate, dorsal anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices both when meditating and when not meditating.[100]

Changes in the brain

Meditation has been shown to change grey matter concentrations and the precuneus.[101][40][102][41][39]

An eight-week MBSR course induced changes in gray matter concentrations.[40] Exploratory whole brain analyses identified significant increases in gray matter concentration in the PCC, TPJ, and the cerebellum. These results suggest that participation in MBSR is associated with changes in gray matter concentration in brain regions involved in learning and memory processes, emotion regulation, self-referential processing, and perspective taking.

Perception

Studies have shown that meditation has both short-term and long-term effects on various perceptual faculties. In 1984 a study showed that meditators have a significantly lower detection threshold for light stimuli of short duration.[103] In 2000 a study of the perception of visual illusions by zen masters, novice meditators, and non-meditators showed statistically significant effects found for the Poggendorff Illusion but not for the Müller-Lyer Illusion. The zen masters experienced a statistically significant reduction in initial illusion (measured as error in millimeters) and a lower decrement in illusion for subsequent trials.[104] Tloczynski has described the theory of mechanism behind the changes in perception that accompany mindfulness meditation thus: "A person who meditates consequently perceives objects more as directly experienced stimuli and less as concepts… With the removal or minimization of cognitive stimuli and generally increasing awareness, meditation can therefore influence both the quality (accuracy) and quantity (detection) of perception."[104] Brown also points to this as a possible explanation of the phenomenon: "[the higher rate of detection of single light flashes] involves quieting some of the higher mental processes which normally obstruct the perception of subtle events." In other words, the practice may temporarily or permanently alter some of the top-down processing involved in filtering subtle events usually deemed noise by the perceptual filters.

Calming and relaxation

According to an article in Psychological Bulletin, EEG activity slows as a result of meditation.[105] The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has written, "It is thought that some types of meditation might work by reducing activity in the sympathetic nervous system and increasing activity in the parasympathetic nervous system," or equivalently, that meditation produces a reduction in arousal and increase in relaxation.

Herbert Benson, founder of the Mind-Body Medical Institute, which is affiliated with Harvard University and several Boston hospitals, reports that meditation induces a host of biochemical and physical changes in the body collectively referred to as the "relaxation response".[106] The relaxation response includes changes in metabolism, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and brain chemistry. Benson and his team have also done clinical studies at Buddhist monasteries in the Himalayan Mountains.[107] Benson wrote The Relaxation Response to document the benefits of meditation, which in 1975 were not yet widely known.[108]

Arousing effects

Although the most common modern characterization of Buddhist meditation is a ‘relaxation’ technique, both scientific studies and Buddhist textual sources proves meditation’s arousing or wake-promoting effects.[109] Meditations aiming at improving meta-cognitive skills and compassion (e.g. loving-kindness meditation) are associated with physiological arousal, compared to breathing meditation.[110] Theravada (i.e.Vipassana) styles of meditation induce relaxation responses, while Vajrayana styles of meditation induce arousal responses.[111] Short term meditation training enables the voluntary activation of the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) results in epinephrine release.[112] When the SNS is activated, human body is turning into ‘fight or flight’ mode, whereas the PNS is termed the ‘rest and digest’ mode.[113] For example, when SNS is activated, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration will be increased, and catecholamines will be produced, while heart rate variability and galvanic skin resistance will be decreased.[113] Therefore, Relaxing meditation seems to correspond to PNS dominance, and arousing meditation seems to correspond to SNS dominance.

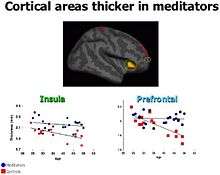

Slowing aging

Aging is a process accompanied by a decrease in brain weight and volume. This phenomenon can be explained by structural changes in the brain, namely, a loss of grey matter. Some studies over the last decade have implicated meditation as a protective factor against normal age-related brain atrophy.[114] The first direct evidence for this link emerged from a study investigating changes in the cortical thickness of meditators. The researchers found that regular meditation practice was able to reduce age-related thinning of the frontal cortex, though these findings were restricted to particular regions of the brain.[115] A similar study looked to further expand on this finding by including a behavioural component. Consistent with the previous study, meditators did not show the expected negative correlation between grey matter volume and age. In addition, the results for meditators on the behavioural test, measuring attentional performance, were comparable across all age groups.[116] This implies that meditation can potentially protect against age-related grey matter loss and age-related cognitive decline. Since then, more research has supported the notion that meditation serves as a neuroprotective factor that slows age-related brain atrophy.[114][117] Still, all studies have been cross sectional in design. Furthermore, these results merely describe associations and do not make causal inferences.[118] Further work using longitudinal and experimental designs may help solidify the causal link between meditation and grey matter loss. Since few studies have investigated this direct link, however insightful they may be, there is not sufficient evidence for a conclusive answer.

Research has also been conducted on the malleable determinants of cellular aging in an effort to understand human longevity. Researchers have stated, "We have reviewed data linking stress arousal and oxidative stress to telomere shortness. Meditative practices appear to improve the endocrine balance toward positive arousal (high DHEA, lower cortisol) and decrease oxidative stress. Thus, meditation practices may promote mitotic cell longevity both through decreasing stress hormones and oxidative stress and increasing hormones that may protect the telomere."[119][120]

Happiness and emotional well-being

Studies have shown meditators to have higher happiness than control groups, although this may be due to non-specific factors such as meditators having better general self-care.[121][122][90][89]

Positive relationships have been found between the volume of gray matter in the right precuneus area of the brain and both meditation and the subject's subjective happiness score.[123][101][40][102][41][39] A recent study found that participants who engaged in a body-scan meditation for about 20 minutes self-reported higher levels of happiness and decrease in anxiety compared to participants who just rested during the 20 minute time-span. These results suggest that an increase in awareness of one's body through meditation causes a state of selflessness and a feeling of connectedness. This result then leads to reports of positive emotions.[124]

A technique knowns as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) displays significant benefits towards one's mental health and coping behaviors. Participants who had no prior experience with MBSR reported a significant increase in happiness after 8 weeks of MBSR practice. Focus on the present moment and increased awareness of one's thoughts can help monitor and reduce judgment or negative thoughts, causing a report of higher emotional well-being.[125]

Potential adverse effects and limits of meditation

The following is an official statement from the US government-run National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health:

"Meditation is considered to be safe for healthy people. There have been rare reports that meditation could cause or worsen symptoms in people who have certain psychiatric problems, but this question has not been fully researched. People with physical limitations may not be able to participate in certain meditative practices involving physical movement. Individuals with existing mental or physical health conditions should speak with their health care providers prior to starting a meditative practice and make their meditation instructor aware of their condition."[126]

Adverse effects have been reported,[127][128] and may, in some cases, be the result of "improper use of meditation".[129] The NIH advises prospective meditators to "ask about the training and experience of the meditation instructor… [they] are considering."[126]

As with any practice, meditation may also be used to avoid facing ongoing problems or emerging crises in the meditator's life. In such situations, it may instead be helpful to apply mindful attitudes acquired in meditation while actively engaging with current problems.[130][131] According to the NIH, meditation should not be used as a replacement for conventional health care or as a reason to postpone seeing a doctor.[126]

Pain

Meditation reduces pain perception.[132]

See also

- Buddhism and psychology

References

- Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M, Tjosvold L, Vandermeer B, Liang Y, Bialy L, Hooton N, Buscemi N, Dryden DM, Klassen TP (June 2007). "Meditation practices for health: state of the research" (PDF). Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (155): 1–263. PMC 4780968. PMID 17764203. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009.

- Lutz A, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ (2007). "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction". In Zelazo PD, Moscovitch M, Thompson E (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 499–552. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511816789.020. ISBN 978-0-511-81678-9.

- Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M, Buscemi N, Dryden DM, Barnes V, Carlson LE, Dusek JA, Shannahoff-Khalsa D (December 2008). "Clinical trials of meditation practices in health care: characteristics and quality". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 14 (10): 1199–213. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0307. PMID 19123875.

- Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma R, Berger Z, Sleicher D, Maron DD, Shihab HM, Ranasinghe PD, Linn S, Saha S, Bass EB, Haythornthwaite JA (March 2014). "Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (3): 357–68. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. PMC 4142584. PMID 24395196.

- Van Dam NT, van Vugt MK, Vago DR, Schmalzl L, Saron CD, Olendzki A, Meissner T, Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Gorchov J, Fox KC, Field BA, Britton WB, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Meyer DE (January 2018). "Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 13 (1): 36–61. doi:10.1177/1745691617709589. PMC 5758421. PMID 29016274.

- Stetka B (October 2017). "Where's the Proof That Mindfulness Meditation Works?". Scientific American.

- Tang YY, Posner MI (January 2013). "Special issue on mindfulness neuroscience". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 8 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1093/scan/nss104. PMC 3541496. PMID 22956677.

- Sequeira S (January 2014). "Foreword to Advances in Meditation Research: neuroscience and clinical applications". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1307 (1): v–vi. Bibcode:2014NYASA1307D...5S. doi:10.1111/nyas.12305. PMID 24571183.

- Awasthi B (2013). "Issues and perspectives in meditation research: in search for a definition". Frontiers in Psychology. 3: 613. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00613. PMC 3541715. PMID 23335908.

- Van Dam NT, van Vugt MK, Vago DR, Schmalzl L, Saron CD, Olendzki A, Meissner T, Lazar SW, Gorchov J, Fox KC, Field BA, Britton WB, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Meyer DE (January 2018). "Reiterated Concerns and Further Challenges for Mindfulness and Meditation Research: A Reply to Davidson and Dahl". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 13 (1): 66–69. doi:10.1177/1745691617727529. PMC 5817993. PMID 29016240.

- Brook RD, Appel LJ, Rubenfire M, Ogedegbe G, Bisognano JD, Elliott WJ, Fuchs FD, Hughes JW, Lackland DT, Staffileno BA, Townsend RR, Rajagopalan S (June 2013). "Beyond Medications and Diet: Alternative Approaches to Lowering Blood Pressure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association". Hypertension. 61 (6): 1360–83. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. PMID 23608661.

- https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-lifestyle/mental-health-and-wellbeing/meditation-to-boost-health-and-wellbeing

- Davidson, Richard J.; Kaszniak, Alfred W. (October 2015). "Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Research on Mindfulness and Meditation". 70 (7): 581–592. doi:10.1037/a0039512. PMC 4627495. PMID 26436310. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sevinc G, Hölzel BK, Hashmi J, Greenberg J, McCallister A, Treadway M, Schneider ML, Dusek JA, Carmody J, Lazar SW (June 2018). "Common and Dissociable Neural Activity After Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Relaxation Response Programs". Psychosomatic Medicine. 80 (5): 439–451. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000590. PMC 5976535. PMID 29642115.

- Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, Pettman D (April 2014). "Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". PLOS One. 9 (4): e96110. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...996110S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096110. PMC 3999148. PMID 24763812.

- Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, Fournier C (June 2015). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 78 (6): 519–28. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009. PMID 25818837.

- Jain FA, Walsh RN, Eisendrath SJ, Christensen S, Rael Cahn B (2014). "Critical analysis of the efficacy of meditation therapies for acute and subacute phase treatment of depressive disorders: a systematic review". Psychosomatics. 56 (2): 140–52. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.007. PMC 4383597. PMID 25591492.

- Simkin DR, Black NB (July 2014). "Meditation and mindfulness in clinical practice". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 23 (3): 487–534. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2014.03.002. PMID 24975623.

- Zoogman S, Goldberg SB, Hoyt WT (January 2014). "Mindfulness Interventions with Youth: A Meta-Analysis". Mindfulness. 59 (4): 297–302. doi:10.1093/sw/swu030.

- Sharma M, Rush SE (October 2014). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: a systematic review". Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 19 (4): 271–86. doi:10.1177/2156587214543143. PMID 25053754.

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D (April 2010). "The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 78 (2): 169–83. doi:10.1037/a0018555. PMC 2848393. PMID 20350028.

- Chiesa A, Serretti A (April 2014). "Are mindfulness-based interventions effective for substance use disorders? A systematic review of the evidence". Substance Use & Misuse. 49 (5): 492–512. doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.770027. PMID 23461667.

- Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO (January 2014). "Mindfulness training targets neurocognitive mechanisms of addiction at the attention-appraisal-emotion interface". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 4 (173): 173. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00173. PMC 3887509. PMID 24454293.

- Black DS (April 2014). "Mindfulness-based interventions: an antidote to suffering in the context of substance use, misuse, and addiction". Substance Use & Misuse. 49 (5): 487–91. doi:10.3109/10826084.2014.860749. PMID 24611846.

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, Maglione MA (April 2017). "Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 51 (2): 199–213. doi:10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2. PMC 5368208. PMID 27658913.

- Godfrey KM, Gallo LC, Afari N (April 2015). "Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 38 (2): 348–62. doi:10.1007/s10865-014-9610-5. PMID 25417199.

- Olson KL, Emery CF (January 2015). "Mindfulness and weight loss: a systematic review". Psychosomatic Medicine. 77 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000127. PMID 25490697.

- Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Griffiths MD (February 2014). "Do mindfulness-based therapies have a role in the treatment of psychosis?". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 48 (2): 124–7. doi:10.1177/0004867413512688. PMID 24220133.

- Chadwick P (May 2014). "Mindfulness for psychosis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 204 (5): 333–4. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136044. PMID 24785766.

- Khoury B, Lecomte T, Gaudiano BA, Paquin K (October 2013). "Mindfulness interventions for psychosis: a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research. 150 (1): 176–84. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.055. PMID 23954146.

- Querstret D, Cropley M (December 2013). "Assessing treatments used to reduce rumination and/or worry: a systematic review". Clinical Psychology Review. 33 (8): 996–1009. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.004. PMID 24036088.

- Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K (April 2015). "How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of meditation studies". Clinical Psychology Review. 37: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006. PMID 25689576.

- Crescentini C, Capurso V (2015). "Mindfulness meditation and explicit and implicit indicators of personality and self-concept changes". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 44. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00044. PMC 4310269. PMID 25688222.

- Crescentini C, Matiz A, Fabbro F (2015). "Improving personality/character traits in individuals with alcohol dependence: the influence of mindfulness-oriented meditation". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 34 (1): 75–87. doi:10.1080/10550887.2014.991657. PMID 25585050.

- "Research Spotlight: Mindfulness Meditation Is Associated With Structural Changes in the Brain". NCCIH. 30 January 2011.

- Zeidan F, Grant JA, Brown CA, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC (June 2012). "Mindfulness meditation-related pain relief: evidence for unique brain mechanisms in the regulation of pain". Neuroscience Letters. 520 (2): 165–73. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.082. PMC 3580050. PMID 22487846.

- Jensen MP, Day MA, Miró J (March 2014). "Neuromodulatory treatments for chronic pain: efficacy and mechanisms". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 10 (3): 167–78. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.12. PMC 5652321. PMID 24535464.

- Malinowski P (2013). "Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 7: 8. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00008. PMC 3563089. PMID 23382709.

- Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC, Hoge EA, Dusek JA, Morgan L, Pitman RK, Lazar SW (March 2010). "Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 5 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp034. PMC 2840837. PMID 19776221.

- Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, Gard T, Lazar SW (January 2011). "Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density". Psychiatry Research. 191 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. PMC 3004979. PMID 21071182.

- Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, Floman JL, Ellamil M, Rumak SP, Sedlmeier P, Christoff K (June 2014). "Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 43: 48–73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016. PMID 24705269.

- Santarnecchi E, D'Arista S, Egiziano E, Gardi C, Petrosino R, Vatti G, Reda M, Rossi A (October 2014). "Interaction between neuroanatomical and psychological changes after mindfulness-based training". PLOS One. 9 (10): e108359. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j8359S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108359. PMC 4203679. PMID 25330321.

- Fox KC, Dixon ML, Nijeboer S, Girn M, Floman JL, Lifshitz M, Ellamil M, Sedlmeier P, Christoff K (June 2016). "Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 65: 208–28. arXiv:1603.06342. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.021. PMID 27032724.

- Kabat-Zinn J (2003). "Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 10 (2): 144–156. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg016.

- Lippelt DP, Hommel B, Colzato LS (2014). "Focused attention, open monitoring and loving kindness meditation: effects on attention, conflict monitoring, and creativity - A review". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 1083. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01083. PMC 4171985. PMID 25295025.

- Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ (April 2008). "Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 12 (4): 163–9. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005. PMC 2693206. PMID 18329323.

- Moore A, Malinowski P (March 2009). "Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility". Consciousness and Cognition. 18 (1): 176–86. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008. PMID 19181542.

- Schmertz SK, Anderson PL, Robins DL (2009). "The relation between self-report mindfulness and performance on tasks of sustained attention". Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 31 (1): 60–66. doi:10.1007/s10862-008-9086-0.

- Slagter HA, Lutz A, Greischar LL, Francis AD, Nieuwenhuis S, Davis JM, Davidson RJ (June 2007). "Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources". PLoS Biology. 5 (6): e138. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050138. PMC 1865565. PMID 17488185.

- Jha AP, Krompinger J, Baime MJ (June 2007). "Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention". Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 7 (2): 109–19. doi:10.3758/cabn.7.2.109. PMID 17672382.

- Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI (April 2002). "Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 14 (3): 340–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.590.8796. doi:10.1162/089892902317361886. PMID 11970796.

- van den Hurk PA, Giommi F, Gielen SC, Speckens AE, Barendregt HP (June 2010). "Greater efficiency in attentional processing related to mindfulness meditation". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 63 (6): 1168–80. doi:10.1080/17470210903249365. PMID 20509209.

- Green, Joseph P.; Black, Katharine N. (2017). "Meditation-focused attention with the MBAS and solving anagrams". Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4 (4): 348–366. doi:10.1037/cns0000113. ISSN 2326-5531.

- Tang YY, Ma Y, Wang J, Fan Y, Feng S, Lu Q, Yu Q, Sui D, Rothbart MK, Fan M, Posner MI (October 2007). "Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (43): 17152–6. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10417152T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707678104. PMC 2040428. PMID 17940025.

- Chan D, Woollacott M (2007). "Effects of level of meditation experience on attentional focus: is the efficiency of executive or orientation networks improved?". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 13 (6): 651–7. doi:10.1089/acm.2007.7022. PMID 17718648.

- Anderson ND, Lau MA, Segal ZV, Bishop SR (2007). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attentional control". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 14 (6): 449–463. doi:10.1002/cpp.544.

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U (November 2011). "How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 6 (6): 537–59. doi:10.1177/1745691611419671. PMID 26168376.

- Fabio RA, Towey GE (February 2018). "Long-term meditation: the relationship between cognitive processes, thinking styles and mindfulness". Cognitive Processing. 19 (1): 73–85. doi:10.1007/s10339-017-0844-3. PMID 29110263.

- Moore A, Gruber T, Derose J, Malinowski P (2012). "Regular, brief mindfulness meditation practice improves electrophysiological markers of attentional control". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 6: 18. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00018. PMC 3277272. PMID 22363278.

- Chawla N, Marlatt GA (2010). Mindlessness-Mindfulness. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. American Cancer Society. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0549. ISBN 9780470479216.

- Baer RA (2003). "Mindfulness Training as a Clinical Intervention: A Conceptual and Empirical Review". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 10 (2): 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bpg015.

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ (May 2005). "The cognitive control of emotion". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 9 (5): 242–9. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. PMID 15866151.

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK (2007). "Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science". Annual Review of Psychology. 58: 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085516. PMID 17029565.

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ (February 2010). "Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder". Emotion. 10 (1): 83–91. doi:10.1037/a0018441. PMC 4203918. PMID 20141305.

- Cuthbert BN, Schupp HT, Bradley MM, Birbaumer N, Lang PJ (March 2000). "Brain potentials in affective picture processing: covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report". Biological Psychology. 52 (2): 95–111. doi:10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00044-7. PMID 10699350.

- Schupp HT, Cuthbert BN, Bradley MM, Cacioppo JT, Ito T, Lang PJ (March 2000). "Affective picture processing: the late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance". Psychophysiology. 37 (2): 257–61. doi:10.1111/1469-8986.3720257. PMID 10731776.

- Schupp HT, Junghöfer M, Weike AI, Hamm AO (June 2003). "Attention and emotion: an ERP analysis of facilitated emotional stimulus processing". NeuroReport. 14 (8): 1107–10. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.521.5802. doi:10.1097/00001756-200306110-00002. PMID 12821791.

- Brown KW, Goodman RJ, Inzlicht M (January 2013). "Dispositional mindfulness and the attenuation of neural responses to emotional stimuli". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 8 (1): 93–9. doi:10.1093/scan/nss004. PMC 3541486. PMID 22253259.

- Ortner CN, Kilner SJ, Zelazo PD (2007). "Mindfulness meditation and reduced emotional interference on a cognitive task". Motivation and Emotion. 31 (4): 271–283. doi:10.1007/s11031-007-9076-7.

- Goldin P, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Hahn K, Gross JJ (January 2013). "MBSR vs aerobic exercise in social anxiety: fMRI of emotion regulation of negative self-beliefs". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 8 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1093/scan/nss054. PMC 3541489. PMID 22586252.

- Farb NA, Segal ZV, Mayberg H, Bean J, McKeon D, Fatima Z, Anderson AK (December 2007). "Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (4): 313–22. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm030. PMC 2566754. PMID 18985137.

- Beblo T, Pelster S, Schilling C, Kleinke K, Iffland B, Driessen M, Fernando S (September 2018). "Breath Versus Emotions: The Impact of Different Foci of Attention During Mindfulness Meditation on the Experience of Negative and Positive Emotions". Behavior Therapy. 49 (5): 702–714. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2017.12.006. PMID 30146138.

- Quirk GJ, Beer JS (December 2006). "Prefrontal involvement in the regulation of emotion: convergence of rat and human studies". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 16 (6): 723–7. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.004. PMID 17084617.

- Chiesa A, Calati R, Serretti A (April 2011). "Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings". Clinical Psychology Review. 31 (3): 449–64. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003. PMID 21183265.

- Sevinc G, Hölzel BK, Hashmi J, Greenberg J, McCallister A, Treadway M, Schneider ML, Dusek JA, Carmody J, Lazar SW (June 2018). "Common and Dissociable Neural Activity After Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Relaxation Response Programs". Psychosomatic Medicine. 80 (5): 439–451. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000590. PMC 5976535. PMID 29642115.

- "Mindfulness, Meditation, Relaxation Response Have Different Effects on Brain Function". 13 June 2018.

- Bostock, Sophie; Crosswell, Alexandra D.; Prather, Aric A.; Steptoe, Andrew (2019). "Mindfulness on-the-go: Effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being". Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 24 (1): 127–138. doi:10.1037/ocp0000118. ISSN 1939-1307. PMC 6215525. PMID 29723001.

- Basso, Julia C.; McHale, Alexandra; Ende, Victoria; Oberlin, Douglas J.; Suzuki, Wendy A. (2019). "Brief, daily meditation enhances attention, memory, mood, and emotional regulation in non-experienced meditators". Behavioural Brain Research. 356: 208–220. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2018.08.023. ISSN 0166-4328. PMID 30153464.

- Surinrut, Piyawan; Auamnoy, Titinun; Sangwatanaroj, Somkiat (2016). "Enhanced happiness and stress alleviation upon insight meditation retreat: mindfulness, a part of traditional Buddhist meditation". Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 19 (7): 648–659. doi:10.1080/13674676.2016.1207618. ISSN 1367-4676.

- Tang YY, Posner MI (January 2013). "Tools of the trade: theory and method in mindfulness neuroscience". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 8 (1): 118–20. doi:10.1093/scan/nss112. PMC 3541497. PMID 23081977.

- Inwongsakul PT (September 2015). Impact of vipassana meditation on life satisfaction and quality of life (Ph.D. thesis). University of Mysore.

- Dargah M (April 2017). The Impact of Vipassana Meditation on Quality of Life (Ph.D. thesis). The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

- Hernández SE, Suero J, Rubia K, González-Mora JL (March 2015). "Monitoring the neural activity of the state of mental silence while practicing Sahaja yoga meditation". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 21 (3): 175–9. doi:10.1089/acm.2013.0450. PMID 25671603.

- Hernández SE, Barros-Loscertales A, Xiao Y, González-Mora JL, Rubia K (February 2018). "Gray Matter and Functional Connectivity in Anterior Cingulate Cortex are Associated with the State of Mental Silence During Sahaja Yoga Meditation". Neuroscience. 371: 395–406. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.12.017. hdl:10234/175002. PMID 29275207.

- Aftanas LI, Golocheikine SA (September 2001). "Human anterior and frontal midline theta and lower alpha reflect emotionally positive state and internalized attention: high-resolution EEG investigation of meditation". Neuroscience Letters. 310 (1): 57–60. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02094-8. PMID 11524157.

- Aftanas L, Golosheykin S (June 2005). "Impact of regular meditation practice on EEG activity at rest and during evoked negative emotions". The International Journal of Neuroscience. 115 (6): 893–909. doi:10.1080/00207450590897969. PMID 16019582.

- Manocha R, Black D, Spiro D, Ryan J, Stough C (March 2010). "Changing Definitions of Meditation – Is there a Physiological Corollary? Skin temperature changes of a mental silence orientated form of meditation compared to rest" (PDF). Journal of the International Society of Life Sciences. 28 (1): 23–31.

- Aftanas LI, Golocheikine SA (September 2002). "Non-linear dynamic complexity of the human EEG during meditation". Neuroscience Letters. 330 (2): 143–6. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00745-0. PMID 12231432.

- Hendriks T (May 2018). "The effects of Sahaja Yoga meditation on mental health: a systematic review". Journal of Complementary & Integrative Medicine. 15 (3). doi:10.1515/jcim-2016-0163. PMID 29847314.

- Manocha R, Black D, Wilson L (2012). "Quality of life and functional health status of long-term meditators". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/350674. PMC 3352577. PMID 22611427.

- Manocha R (2014). "Meditation, mindfulness and mind-emptiness". Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 23: 46–7. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5215.2010.00519.x.

- Morgon A. Sahaja Yoga: an Ancient Path to Modern Mental Health? (Doctor of Clinical Psychology thesis). University of Plymouth.

- Watts V (2016). "Kundalini Yoga Found to Enhance Cognitive Functioning in Older Adults". Psychiatric News. 51 (9): 1. doi:10.1176/appi.pn.2016.4b11.

- Krisanaprakornkit T, Krisanaprakornkit W, Piyavhatkul N, Laopaiboon M (January 2006). "Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004998. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2. PMID 16437509.

- Lyn Freeman, Mosby’s Complementary & Alternative Medicine: A Research-Based Approach, Mosby Elsevier, 2009, p. 163

- Ernst E (2011). Bonow RO, et al. (eds.). Chapter 51: Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Management of Patients with Heart Disease. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine (9th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-2708-1.

A systematic review of six RCTs of transcendental meditation failed to generate convincing evidence that meditation is an effective treatment for hypertension

(References the same 2004 systematic review by Canter and Ernst on TM and hypertension that is separately referenced in this article) - Canter PH, Ernst E (November 2004). "Insufficient evidence to conclude whether or not Transcendental Meditation decreases blood pressure: results of a systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Journal of Hypertension. 22 (11): 2049–54. doi:10.1097/00004872-200411000-00002. PMID 15480084.

- Krisanaprakornkit T, Ngamjarus C, Witoonchart C, Piyavhatkul N (June 2010). "Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006507. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2. PMID 20556767.

- Canter PH, Ernst E (November 2003). "The cumulative effects of Transcendental Meditation on cognitive function--a systematic review of randomised controlled trials". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 115 (21–22): 758–66. doi:10.1007/BF03040500. PMID 14743579.

- Brewer JA, Worhunsky PD, Gray JR, Tang YY, Weber J, Kober H (December 2011). "Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (50): 20254–9. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820254B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108. JSTOR 23060108. PMC 3250176. PMID 22114193.

- Kurth F, Luders E, Wu B, Black DS (2014). "Brain Gray Matter Changes Associated with Mindfulness Meditation in Older Adults: An Exploratory Pilot Study using Voxel-based Morphometry". Neuro. 1 (1): 23–26. doi:10.17140/NOJ-1-106. PMC 4306280. PMID 25632405.

- Kurth F, MacKenzie-Graham A, Toga AW, Luders E (January 2015). "Shifting brain asymmetry: the link between meditation and structural lateralization". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 10 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu029. PMC 4994843. PMID 24643652.

- Brown D, Forte M, Dysart M (June 1984). "Differences in visual sensitivity among mindfulness meditators and non-meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 58 (3): 727–33. doi:10.2466/pms.1984.58.3.727. PMID 6382144.

- Tloczynski J, Santucci A, Astor-Stetson E (December 2000). "Perception of visual illusions by novice and longer-term meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 91 (3 Pt 1): 1021–6. doi:10.2466/pms.2000.91.3.1021. PMID 11153836.

- Cahn BR, Polich J (March 2006). "Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (2): 180–211. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180. PMID 16536641.

- Benson H (December 1997). "The relaxation response: therapeutic effect". Science. 278 (5344): 1694–5. Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1693B. doi:10.1126/science.278.5344.1693b. PMID 9411784.

- Cromie, William J. (18 April 2002). "Meditation changes temperatures: Mind controls body in extreme experiments". Harvard University Gazette. Archived from the original on 24 May 2007.

- Benson H (2001). The Relaxation Response. HarperCollins. pp. 61–3. ISBN 978-0-380-81595-1.

- Britton, W, Lindahl, J, Cahn, B, Davis, J, Goldman, R (2014). "Awakening is not a metaphor: The effects of buddhist meditation practices on basic wakefulness". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 13071 (1): 64–81. doi:10.1111/nyas.12279. PMC 4054695. PMID 24372471.

- Lumma, A, Kok, B, Singer, T (2015). "Is meditation always relaxing? investigating heart rate, heart rate variability, experienced effort and likeability during training of three types of meditation". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 97 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.04.017. PMID 25937346.

- Amihai, I, Maria, K (2014). "Arousal vs. relaxation: A comparison of the neurophysiological and cognitive correlates of vajrayana and theravada meditative practices". PLoS One. 9 (7).

- Kox, M, Eijk, L, Zwaag, J, Wildenberg, J, Sweep, F, Hoeven, J, Pickkers, P (2014). "Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans". National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (20): 7379–7384. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322174111. PMC 4034215. PMID 24799686.

- Brodal, Per (2004). The Central Nervous System: Structure and Function (3 ed.). Oxford University Press US. pp. 369–396. ISBN 978-0-19-516560-9.

- Luders E, Cherbuin N, Kurth F (2015). "Forever Young(er): potential age-defying effects of long-term meditation on gray matter atrophy". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 1551. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01551. PMC 4300906. PMID 25653628.

- Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Wasserman RH, Gray JR, Greve DN, Treadway MT, McGarvey M, Quinn BT, Dusek JA, Benson H, Rauch SL, Moore CI, Fischl B (November 2005). "Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness". NeuroReport. 16 (17): 1893–7. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19. PMC 1361002. PMID 16272874.

- Pagnoni G, Cekic M (October 2007). "Age effects on gray matter volume and attentional performance in Zen meditation". Neurobiology of Aging. 28 (10): 1623–7. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.06.008. PMID 17655980.

- Kurth F, Cherbuin N, Luders E (June 2015). "Reduced age-related degeneration of the hippocampal subiculum in long-term meditators". Psychiatry Research. 232 (3): 214–8. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.03.008. PMID 25907419.

- Luders E (January 2014). "Exploring age-related brain degeneration in meditation practitioners". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1307 (1): 82–88. Bibcode:2014NYASA1307...82L. doi:10.1111/nyas.12217. PMID 23924195.

- Epel E, Daubenmier J, Moskowitz JT, Folkman S, Blackburn E (August 2009). "Can meditation slow rate of cellular aging? Cognitive stress, mindfulness, and telomeres". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1172 (1): 34–53. Bibcode:2009NYASA1172...34E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04414.x. PMC 3057175. PMID 19735238.

- Ornish D, Lin J, Chan JM, Epel E, Kemp C, Weidner G, et al. (October 2013). "Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study". The Lancet. Oncology. 14 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70366-8. PMID 24051140. Lay summary – University of California San Francisco News Center.

- Ramesh MG, Sathian B, Sinu E, Kiranmai SR (October 2013). "Efficacy of rajayoga meditation on positive thinking: an index for self-satisfaction and happiness in life". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 7 (10): 2265–7. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/5889.3488. PMC 3843423. PMID 24298493.

- Campos D, Cebolla A, Quero S, Bretón-López J, Botella C, Soler J, García-Campayo J, Demarzo M, Baños RM (2016). "Meditation and happiness: Mindfulness and self-compassion may mediate the meditation–happiness relationship". Personality and Individual Differences. 93: 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.040. hdl:10234/157867.

- Sato W, Kochiyama T, Uono S, Kubota Y, Sawada R, Yoshimura S, Toichi M (November 2015). "The structural neural substrate of subjective happiness". Scientific Reports. 5: 16891. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516891S. doi:10.1038/srep16891. PMC 4653620. PMID 26586449.

- Dambrun M (November 2016). "When the dissolution of perceived body boundaries elicits happiness: The effect of selflessness induced by a body scan meditation". Consciousness and Cognition. 46: 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2016.09.013. PMID 27684609.

- Anderson ND, Lau MA, Segal ZV, Bishop SR (2007). "Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attentional control". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 14 (6): 449–463. doi:10.1002/cpp.544.

- "Meditation: An Introduction". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. June 2010.

- Perez-De-Albeniz A, Holmes J (2000). "Meditation: Concepts, effects and uses in therapy". International Journal of Psychotherapy. 5 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1080/13569080050020263.

- Rocha T (25 June 2014). "The Dark Knight of the Soul". The Atlantic.

- Turner RP, Lukoff D, Barnhouse RT, Lu FG (July 1995). "Religious or spiritual problem. A culturally sensitive diagnostic category in the DSM-IV". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 183 (7): 435–44. doi:10.1097/00005053-199507000-00003. PMID 7623015.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG (1999). "3". Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York: Guilford. ISBN 978-1-57230-481-9.

- Metzner R (2005). "Psychedelic, Psychoactive and Addictive Drugs and States of Consciousness". In Earlywine M (ed.). Mind-Altering Drugs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 25–48. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195165319.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-516531-9.

- Nakata H, Sakamoto K, Kakigi R (2014). "Meditation reduces pain-related neural activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, secondary somatosensory cortex, and thalamus". Frontiers in Psychology. 5: 1489. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01489. PMC 4267182. PMID 25566158.

External links