Rape in Pakistan

Rape in Pakistan came to international attention after the politically sanctioned rape of Mukhtaran Bibi.[1][2] The group War Against Rape (WAR) has documented the severity of rape in Pakistan, and the police indifference to it.[3] According to Women's Studies professor Shahla Haeri, rape in Pakistan is "often institutionalized and has the tacit and at times the explicit approval of the state".[4][5] According to lawyer Asma Jahangir, who was a co-founder of the women's rights group Women's Action Forum, up to seventy-two percent of women in custody in Pakistan are physically or sexually abused.[6]

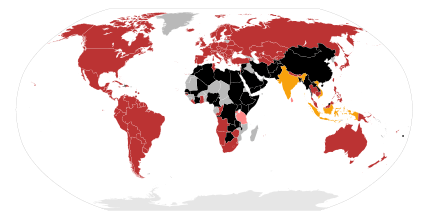

| Rape |

|---|

| Types |

|

| Effects and motivations |

|

| By country |

| During conflicts |

|

| Laws |

|

| Related articles |

|

|

Early History

In 1979, Pakistan lawmakers enforced changes to the laws in which rape was considered to be a crime and those who committed it were punishable for the act.[7] This was the first in Pakistan in which acts such as rape and adultery were regarded as crimes.[8]The reinforcement of this new law was referred to as The Offence of Zina.[9] Before 1979, section 375 of the Pakistan Penal Code, stated that girls younger than the age of fourteen were prohibited from sex acts even if consent was acquired.[10] Despite this, the previous laws also claims that rape during marriage is not considered rape as long as if the wife is over the age of fourteen.[11] The changes in the law enforced in 1979, changed the ways of punishment from imprisonment and fines to punishments such as stoning to death.[12] Although this new law is stated to protect women, it reinforces that in order to do so there must be concrete evidence. The evidence was most commonly deemed to be a witness who could testify that the rape actually occurred. During 1979, the witness had to be a muslim male and had to be deemed as credible and honest by the Qazi.[13]

According to this 1979 Zina law, rape is defined as:

(a) the sex is occurring against the will of the person[14]

(b) the individual did not consent to partaking in sexual intercourse[15]

(c) the perpetrator obtains consent by the victim by threatening, hurting or causing fear to the victim.[16]

(d) the perpetrator and victim are not married[17]

Notable cases

Since 2000, various women and teenage girls have begun to speak out after being sexually assaulted. Going against the tradition that a woman should suffer in silence, they have lobbied news outlets and politicians.[18] A recent report from the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan estimated that in 2009, 46 percent of unlawful female killings in Pakistan were "honour killings".[19]

- In 2002, 30-year-old Mukhtaran Bibi (Mukhtār Mā'ī) was gang raped on the orders of the village council as an "honour rape" after allegations that her 12-year-old brother had had sexual relations with a woman from a higher caste.[20] Although custom would expect her to commit suicide after being raped,[21][22][23] Mukhtaran spoke up, and pursued the case, which was picked up by both domestic and international media. On 1 September 2002, an anti-terrorism court sentenced 6 men (including the 4 rapists) to death for rape. In 2005, the Lahore High Court cited "insufficient evidence" and acquitted 5 of the 6 convicted, and commuted the punishment for the sixth man to a life sentence. Mukhtaran and the government appealed this decision, and the Supreme Court suspended the acquittal and held appeal hearings.[24] In 2011, the Supreme Court too acquitted the accused. Mukhtār Mā'ī's story was the subject of a Showtime (TV network) documentary called Shame, directed by Mohammed Naqvi,[25] which won awards including a TV Academy Honor (Special Emmy) of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.[26]

- In 2005, a woman claimed to have been gang raped by four police officers for refusing to pay them a bribe so her husband would be released from prison. One officer was arrested and three have disappeared.

- A 23-year-old woman in Faisalabad made public accusations against the police, saying her husband had been arrested for creating forged documents; she alleges she was raped on the orders of the chief of police for her actions. The officer was suspended but not arrested.[27]

- Kainat Soomro was a 13-year-old schoolgirl when she was kidnapped and gang raped for four days. Her protest has led to the murder of her brother, a death sentence from the elders of her village, and threats from the rapists, who after four years still remain at large.[28]

- Shazia Khalid was raped in Balochistan in the ruling of Pervez Musharaf.

- In 2012, three members of the Border Police were remanded into custody for raping five women aged between fifteen and twenty-one. The women claim they were taken from a picnic area to the police station in Dera Ghazi Khan, where the police filmed themselves sexually assaulting the women.[29]

- In January 2014, a village council ordered gang-rape that was carried out in the same Muzaffargarh district where the Mukhtaran Bibi took place in 2002.[30]

- In the 2014 Layyah rape murder incident, on 19 June 2014, a 21-year-old woman was gang raped and murdered in Layyah district, Punjab province of Pakistan.[31]

- In September 2014, three sons of Mian Farooq, a ruling party parliamentarian from Faisalabad, were accused of abducting and gang raping of a teenage girl. The rapists were later released by the court.[32]

- In July 2017, a panchayat ordered rape of a 16-year-old girl in Multan as punishment for her brother's conduct.[33]

- In December 2017, a 25-year-old girl was gang-raped by four dacoits during a robbery at her house in Multan.[34]

- In December 2017, A girl who married against the wishes of her family was allegedly raped by influential members of a panchayat.[35]

January 2018

In January 2018, a seven-year-old girl named Zainab Ansari was raped and strangled to death in Kasur. The incident caused nationwide outrage in Pakistan.[36] The same month, a 16-year-old girl was raped and killed in Sargodha,[37] and a day later, in the same city, a 13-year-old boy was intoxicated and sexually assaulted by two men belonging to an influential family.[38] In Faisalabad, the same day, a 15-year-old boy was found dead. The later medical reports confirmed a sexual assault.[39] A few days later, the dead body of a 3-year-old girl, named Asma, was found in Mardan, who had been reportedly missing for 24 hours.[40] Her postmortem report points that she had been raped before her murder.[41][42]

UNODC Goodwill Ambassador Shehzad Roy collaborated with Bilawal Bhutto to introduce awareness about education against child sexual abuse in Sindh.[43][44][45]

Issues

The group War Against Rape (WAR) has documented the severity of the rape problem in Pakistan and of police indifference to it.[46] WAR is an NGO whose mission is to publicize the problem of rape in Pakistan; in a report released in 1992, of 60 reported cases of rape, 20% involved police officers. In 2008 the group claimed that several of its members were assaulted by a religious group as they tried to help a woman who had been gang raped identify her assailants.[47]

According to a study carried out by Human Rights Watch there is a rape once every two hours,[48] a gang rape every hour [49][50] and 70-90 percent women are suffering with some kind of domestic violence.[48]

According to Women's Studies professor Shahla Haeri, rape in Pakistan is "often institutionalized and has the tacit and at times the explicit approval of the state".[5] According to a study by Human Rights Watch, there is a rape once every two hours[48] and a gang rape every eight.[50] Asma Jahangir, a lawyer and co-founder of the women's rights group Women's Action Forum, reported in a 1988 study of female detainees in Punjab that around 72 percent of them stated they had been sexually abused while in custody.[51]

Marital Rape

In Pakistan, approximately 70-90% of women face some form of domestic abuse during their lifetime.[52] Marital rape is a common form of spousal abuse as it is not considered to be a crime under the Zina laws.[53] Many men and women in Pakistan are raised with the beliefs that "sex is a man's right in marriage".[54] Women are instilled with the concept that their purpose in society is to fulfill a man's desires as well as to bear children.[55] The topic of sex is a taboo subject in Pakistan, therefore women often refrain from reporting their experiences with rape.[56] Marital abuse in general is considered to be a family and private matter in Pakistan which is another reason of why women refrain from reporting in fear of social judgement.[57] Non consensual marital sex can lead to issues with reproductive health, unsafe sex, as well as pregnancies.[58] Studies show that martial rape continues through out the course of pregnancies, as well as can lead to the birth of numerous babies.[59] Studies show that marital rape commonly occurs in Pakistan because of the husband's desire to have more children and in particular, to have sons.[60]

Child sexual abuse

Child sexual abuse is widespread in Pakistani Islamic schools.[61] In a study of child sexual abuse in Rawalpindi and Islamabad, out of a sample of 300 children 17% claimed to have been abused and in 1997 one child a day was reported as raped, gang raped or kidnapped for sexual gratification.[62] In September 2014, the British Channel 4 broadcast a documentary called Pakistan's Hidden Shame, directed by Mohammed Naqvi and produced by Jamie Doran,[63][64] which highlighted the problem of sexual abuse of street children in particular, an estimated 90 percent of whom have been sexually abused.

The legal system

Honour killings, burnings, and rapes in Pakistan can be seen as indicating inadequate legal protection for women.[77] In 1979 Pakistan passed into law the Hudood Ordinance, which made all forms of extra-marital sex, including rape, a crime against the state.[78][79]

In 2006, the Women's Protection Bill was passed by parliament.

Rape is punishable by death or imprisonment. Gang rape is punished exclusively by death according to the Zinah Al-Jabr(rape) law of the Hudood ordinances.

Corporal punishment is an option for rapists sentenced to imprisonment.

Attitudes

Rape in Pakistan came to international attention after Mukhtaran Bibi charged her attackers with rape and spoke out about her experiences.[1][27] She was then denied the right to leave the country. The matter of her refused visit to the US was raised in an interview by the Washington Post with the then President of Pakistan, General Pervez Musharraf, who claimed to champion "Moderate Islam" that "respect the rights of women", and complained that his country is "unfairly portrayed as a place where rape and other violence against women are rampant and frequently condoned".[80] He said that he had relented over allowing her to leave the country, and remarked that being raped had "become a money-making concern", a way to get rich abroad. This statement provoked an uproar, and Musharraf later denied having made it.[80]

The statement was made in the light of the fact that another rape victim, Dr Shazia Khalid, had left Pakistan, was living in Canada, and had spoken out against official attitudes to rape in Pakistan. Musharraf said of her: "It is the easiest way of doing it. Every second person now wants to come up and get all the [pause] because there is so much of finances. Dr. Shazia, I don't know. But maybe she's a case of money (too), that she wants to make money. She is again talking all against Pakistan, against whatever we've done. But I know what the realities are."[81]

On 29 May 2013, the Council of Islamic Ideology, a constitutional body responsible for giving legal advice on Islamic issues to the Government of Pakistan and the Parliament, declared that DNA tests are not admissible as the main evidence in rape cases. A spokesman for the council said that DNA evidence could, at best, serve as supplementary evidence but could not supersede the Islamic laws laid out for determining rape complaints.[82]

See also

- Human trafficking in Pakistan

- Domestic violence in Pakistan

Regional:

- Rape in India

General:

- Women in Pakistan

References

- Laird, Kathleen Fenner (2008). Whose Islam? Pakistani Women's Political Action Groups Speak Out. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-549-46556-0.

- Khan, Aamer Ahmed (8 September 2005). "Pakistan's real problem with rape". BBC.

- Karim, Farhad (1996). Contemporary Forms of Slavery in Pakistan. Human Rights Watch. p. 72. ISBN 978-1564321541.

- Reuters (10 April 2015). "Lahore gets first women-only auto-rickshaw to beat 'male pests'". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Haeri, Shahla (2002). No Shame for the Sun: Lives of Professional Pakistani Women (1st ed.). Syracuse University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0815629603.

- Goodwin, Jan (2002). Price of Honor: Muslim Women Lift the Veil of Silence on the Islamic World. Plume. p. 51. ISBN 978-0452283770.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Noor, Azman bin Mohd (15 July 2012). "Prosecution of Rape in Islamic Law: A Review of Pakistan Hudood Ordinance 1979". IIUM Law Journal. 16 (2). doi:10.31436/iiumlj.v16i2.55. ISSN 2289-7852.

- Afsaruddin, Asma (2000). Hermeneutics and Honor: Negotiating Female Public Space in Islamic/Ate Societies. Harvard University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-932885-21-0.

- Nosheen, Habiba; Schellmann, Hilke (28 September 2011). "Refusing to Kill Daughter, Pakistani Family Defies Tradition, Draws Anger". The Atlantic.

- Greenberg, Jerrold S.; Clint E. Bruess; Sarah C. Conklin (10 March 2010). "Marital Rape". Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality (4th revised ed.). Jones and Bartlett. ISBN 978-0-7637-7660-2.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (29 September 2004). "Sentenced to Be Raped". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Masood, Salman (17 March 2009). "Pakistani Woman Who Shattered Stigma of Rape Is Married". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Pakistani rape survivor turned education crusader honoured at UN". UN News Centre. United Nations. 2 May 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Pakistan rape acquittals rejected". BBC News. 28 June 2005.

- Kenny, Joanne (20 January 2006). "Curtain rises on Showtime's fall slate". C21 Media.

- "Second Annual Television Academy Honors to Celebrate Eight Programs that Exemplify 'Television with a Conscience'". Television Academy. 20 October 2009.

- Khan, Aamer Ahmed (8 September 2005). "Pakistan's real problem with rape". BBC.

- Crilly, Rob (26 December 2010). "Pakistan's rape victim who dared to fight back". The Telegraph.

- "Pakistan policemen accused of drunken rape". New Zealand Herald. AFP. 22 June 2012.

- Malik Tahseen Raza, 'Panchayat returns, orders ‘gang-rape’', Dawn, 31 January 2014

- "Pakistan woman raped and hanged from tree". The Times of India. AFP. 21 June 2014.

- Nadeem, Azhar (13 September 2014). "Three Sons of PMLN Lawmaker Booked for Raping Teenager in Faisalabad". Pakistan Tribune.

- "Multan panchayat orders rape of alleged rapist's sister". Dunya News. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Four robbers accused of gang raping woman during heist killed in Multan encounter". The Express Tribune. 30 December 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Hussain, Kashif (27 December 2017). "Newly married woman in Faisalabad repeatedly raped by panchayat members, in-laws allege". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Protests in Pakistan over inaction on rape and murder of girl, seven". The Guardian. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Girl raped, killed in Sargodha a day after Kasur tragedy". The Express Tribune. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "13-year-old boy intoxicated, sexually assaulted by two men in Sargodha". Dawn. 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Faisalabad student murdered after 'rape' as nation mourns Zainab". The News International. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Riaz Khan (16 January 2018). "Missing girl found dead after 24 hours". The Nation. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Arshad Aziz Malik (17 January 2018). "Autopsy confirms Asma raped before murder in Mardan". The News. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Shehbaz condemns murder of 3-year-old Asma in Mardan, urges to fight political battles later". Daily Times. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Shehzad Roy calls Kasur incident 'heart-wrenching', demands justice". Geo News. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Sindh govt to introduce awareness on child sexual abuse in school curriculum". The Express Tribune. 15 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Sindh approves life skills based education for class 6 to 9". Geo News. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Karim, Farhad (1996). Contemporary Forms of Slavery in Pakistan. Human Rights Watch. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-56432-154-1.

- "Rape case muddied by claims of 3 parties". Daily Times. 20 March 2008.

- Gosselin, Denise Kindschi (2009). Heavy Hands: An Introduction to the Crime of Intimate and Family Violence (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 13. ISBN 978-0136139034.

- Aleem, Shamim (2013). Women, Peace, and Security: (An International Perspective). p. 64. ISBN 9781483671123.

- Foerstel, Karen (2009). Issues in Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Class: Selections. Sage. p. 337. ISBN 978-1412979672.

- Jahangir, Asma; Jilani, Hina (1990). The Hudood Ordinances: A Divine Sanction?. Lahore: Rhotas Books. p. 137.; cited in Human Rights Watch (1992). "Double Jeopardy: Police Abuse of Women in Pakistan" (PDF). p. 26. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Ali, Faridah A.; Israr, Syed M.; Ali, Badar S.; Janjua, Naveed Z. (1 December 2009). "Association of various reproductive rights, domestic violence and marital rape with depression among Pakistani women". BMC Psychiatry. 9 (1): 77. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-9-77. ISSN 1471-244X.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Hussain, Rafat; Khan, Adeel (28 April 2008). "Women's Perceptions and Experiences of Sexual Violence in Marital Relationships and Its Effect on Reproductive Health". Health Care for Women International. 29 (5): 468–483. doi:10.1080/07399330801949541. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 18437595.

- Gannon, Kathy (21 November 2017). "Sexual abuse is pervasive in Islamic schools in Pakistan". Associated Press. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Rasheed, Shaireen (2004). Jyotsna Pattnaik (ed.). Childhood In South Asia: A Critical Look At Issues, Policies, And Programs. Information Age. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-59311-020-8.

- "Pakistan's Hidden Shame". Channel 4. 1 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- O'Connor, Coilin (9 September 2014). "New Film Lays Bare 'Pakistan's Hidden Shame'". Radio Free Europe.

- "India Has A Rape Crisis, But Pakistan's May Be Even Worse". International Business Times. 13 January 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "ASIA/PAKISTAN - Women in Pakistan: Christian girls raped by Muslims". Pontifical Mission Society. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "Targeting Hindu girls for rape". Express Tribune. 4 January 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "World Report 2013: Pakistan". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- Sonwalkar, Prasun (12 February 2016). "Plight of Ahmadiyyas: MPs want British govt to review aid to Pakistan". Hindustan Times, London. Archived from the original on 3 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "Christian woman gang raped by three Muslim men in Pakistan". Christianity Today. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Rape of Christian Girl in Pakistan Ignored by Police". Worthy News. 11 August 2002. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- "Pakistan Christian Community Outraged Following Rape of 12-Year-Old Girl by Muslim Men". Christian Post. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- "Pakistan Christian Community Outraged Christian Woman Gang-Raped in Pakistan as Attacks Against Believers Escalate". Christian Post. 26 July 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- "17-year-old Christian woman in Pakistan raped during Muslim celebration of Eid al-Fitr". Barnabas Fund News. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Javaid, Maham (28 January 2016). "Pakistan's history of rape impunity". Al Jazeera.

- Ilyas, Faiza (1 August 2015). "Woman speaks of forced conversion, denial to lodge FIR of rape, trafficking". Dawn.

- Datta, Rekha (2010). Beyond Realism: Human Security in India and Pakistan in the Twenty-First Century. Lexington. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7391-2155-9.

- Reports of problems with reporting and prosecuting rape persist.<ref>Childress, Sarah (8 May 2013). "The Stigma of Reporting a Rape in Pakistan". PBS.

- Ahmed, Beenish (11 January 2013). "Pakistan also has a rape problem". Global Post Public Radio website.

- "Musharraf is 'Silly and Stupid' says Washington Post". South Asia Tribune. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Amir, Ayaz (26 September 2005). "Blundering Musharraf begins to lose his balance". South Asia Tribune. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Rape cases: DNA tests not admissible as main evidence says CII". tribune.com.pk. 30 May 2013.