Promin

Promin, or sodium glucosulfone is a sulfone drug that was investigated for the treatment of malaria,[1] tuberculosis[2] and leprosy.[3] It is broken down in the body to dapsone, which is the therapeutic form.[4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sodium glucosulfone, Aceprosol, Promanide, Tasmin, Sulfona P |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.241 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

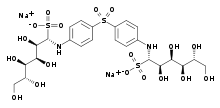

| Formula | C24H36N2O18S3 |

| Molar mass | 736.74024 g/mol g·mol−1 |

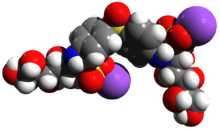

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

History

The first synthesis of Promin is sometimes credited to Edward Tillitson and B.F. Tuller of Parke, Davis, & Co. pharmaceuticals in August 1937.[5][6] However, although Parke-Davis did in fact synthesize the compound, it seems certain that they were not the first; in cooperation with J. Wittmann, Emil Fromm synthesised various sulfone compounds in 1908, including both dapsone and some of its derivatives, such as promin. Fromm and Wittmann however were engaged on chemical rather than medical work, and no-one investigated the medical value of such compounds until some decades afterwards.[6] The medical evaluation of sulfones was inspired by the discovery of the unprecedented value of synthetic compounds such as sulfonamides in treating microbial diseases. Early investigations yielded disappointing results, but subsequently promin and dapsone proved valuable in treating mycobacterial diseases. They were the first treatments to show more than a glimmer of hope of controlling such infections.[7]

Initially, Promin appeared to be safer than dapsone, so it was further investigated at the Mayo Clinic as a treatment for tuberculosis in a guinea pig model.[8] Because it was already known that leprosy and tuberculosis were both caused by mycobacteria (Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, respectively), Guy Henry Faget of the National Leprosarium in Carville, Louisiana, requested information about the drug from Parke-Davis. They, in turn, informed him of the work being done on leprosy in rats by Edmund Cowdry at the Washington University School of Medicine. His successful results, published in 1941, convinced Faget to begin human studies, both with promin and sulfoxone sodium, a related compound from Abbott Laboratories. The initial trials were on six volunteers, and were then expanded and replicated in different locations. Despite severe side effects that caused the initial tests to be suspended temporarily, the drug was shown to be effective.[8][9] This breakthrough was reported worldwide, and led to a reduction in the stigma attached to leprosy, and consequent better treatment of patients, at the time still referred to as "inmates", and forbidden from using public transport.[10]

Pharmacology

Promin is heat-stable and water-soluble, and can therefore be heat-sterilized.[11] It can be injected intravenously,[11] and is available in ampules.[12]

Beyond its solubility, however, promin was later found to have no real advantages over the simpler compound dapsone (which is administered in tablet form). Promin and other sulfones can also not be used as substitutes for dapsone when intolerance develops, as this is a general reaction to sulfones, and not specific to dapsone.[13]

Today, the drugs of choice for treating leprosy are dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine.[14]

References

- Leo B. Slater (2009). War and disease: biomedical research on malaria in the twentieth century. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8135-4438-0.

- David Lilienfeld; Prof Dona Schneider (2011). Public Health: The Development of a Discipline, Volume 2, Twentieth-Century Challenges, vol. 2. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-8135-5009-1.

- Faget GH, et al. (1943) The Promin Treatment of Leprosy, Public Health Report 58:1729-1741, (Reprint Int J Lepr 34(3), 298-310, 1966)

- McDougall AC (June 1979). "Dapsone". Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 4 (2): 139–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1979.tb01608.x. PMID 498567.

- Johansen E.A. "Current Data on Promin Therapy; reprinted in The Star October-December 2003" (PDF).

- Wozel, Gottfried; The Story of Sulfones in Tropical Medicine and Dermatology; International Journal of Dermatology, Volume 28, Issue 1, pages 17–21, January 1989. Published online as: doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb01301.x at URL: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb01301.x/pdf

- Desikan, K. V.; Multi-drug Regimen in Leprosy and its impact on Prevalence of the Disease; MJAFI (Medical Journal, Armed Forces India) 2003; 59 : 2-4

- Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug discovery: a history. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- John Tayman (2006), The Colony, Simon and Schuster. Page 252.

- "Hope for Lepers". Time Magazine. 30 December 1946. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- Singh, R. (2002). Synthetic Drugs. Mittal Publications. p. 291. ISBN 978-81-7099-831-0.

- Clinical Leprosy. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd. 2004. ISBN 978-81-8061-283-1.

- Textbook Of Pharmacology. Elsevier India Pvt. Ltd. 2008. pp. X–87. ISBN 978-81-312-1158-8.

- Ravina, E.; Kubinyi, H. (2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. p. 80. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.