Portuguese man o' war

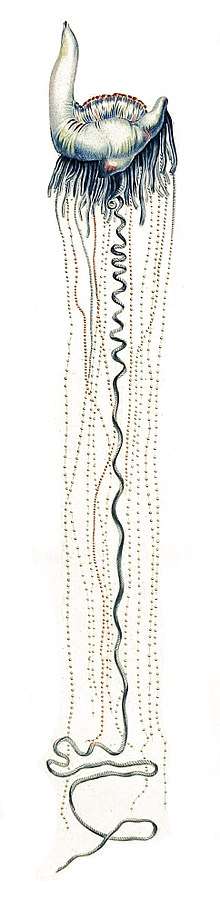

The Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis), also known as the man-of-war,[6] is a marine hydrozoan found in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is one of two species in the genus Physalia, along with the Pacific man o' war (or Australian blue bottle), Physalia utriculus.[7] Physalia is the only genus in the family Physaliidae. Its long tentacles deliver a painful sting, which is venomous and powerful enough to kill fish and even humans.[8] Despite its appearance, the Portuguese man o' war is not a true jellyfish but a siphonophore, which is not actually a single multicellular organism (true jellyfish are single organisms), but a colonial organism made up of many specialized animals of the same species, called zooids or polyps.[9] These polyps are attached to one another and physiologically integrated, to the extent that they cannot survive independently, creating a symbiotic relationship, requiring each polyp to work together and function like an individual animal.

| Portuguese man o' war | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Order: | Siphonophorae |

| Suborder: | Cystonectae |

| Family: | Physaliidae Brandt, 1835[1] |

| Genus: | Physalia Lamarck, 1801[2] |

| Species: | P. physalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Physalia physalis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Name

The name "man o' war" comes from the man-of-war, an 18th-century sailing warship,[10] and the cnidarian's resemblance to the Portuguese version at full sail.[11][5][6]

The names for the animal in Hawaiʻian include ʻili maneʻo, palalia, and others.[12]

In Australia, South Africa and New Zealand, they are also referred to as Blue Bottles.

Habitat

The Atlantic Portuguese man o' war lives at the surface of the ocean. The gas-filled bladder, or pneumatophore, remains at the surface, while the remainder is submerged.[13] Portuguese men o' war have no means of propulsion, and move driven by the winds, currents, and tides. Although they are most commonly found in the open ocean in tropical and subtropical regions, they have been found as far north as the Bay of Fundy, Cape Breton and the Hebrides.[14]

Strong winds may drive them into bays or onto beaches. Often, finding a single Portuguese man o' war is followed by finding many others in the vicinity.[15] They can sting while beached; the discovery of a man o' war washed up on a beach may lead to the closure of the beach.[16][17]

Structure

Being a colonial siphonophore, the Portuguese man o' war is composed of three types of medusoids (gonophores, siphosomal nectophores, and vestigial siphosomal nectophores) and four types of polypoids (free gastrozooids, gastrozooids with tentacles, gonozooids, and gonopalpons), grouped into cormidia beneath the pneumatophore, a sail-shaped structure filled with gas.[15][18] The pneumatophore develops from the planula, unlike the other polyps.[19] This sail is bilaterally symmetrical, with the tentacles at one end. It is translucent, and is tinged blue, purple, pink, or mauve. It may be 9 to 30 cm (3.5 to 11.8 in) long and may extend as much as 15 cm (5.9 in) above the water. The Portuguese man o' war fills its gas bladder with up to 14% carbon monoxide. The remainder is nitrogen, oxygen, and argon—atmospheric gases that diffuse into the gas bladder. Carbon dioxide also occurs at trace levels.[20] The sail is equipped with a siphon. In the event of a surface attack, the sail can be deflated, allowing the colony to temporarily submerge.[21]

The other three polyp types are known as dactylozooid (defense), gonozooid (reproduction), and gastrozooid (feeding).[22] These polyps are clustered. The dactylozooids make up the tentacles that are typically 10 m (33 ft) in length, but can reach over 30 m (98 ft).[15][23] The long tentacles "fish" continuously through the water, and each tentacle bears stinging, venom-filled nematocysts (coiled, thread-like structures), which sting, paralyze, and kill adult or larval squids and fishes. Large groups of Portuguese man o' war, sometimes over 1,000 individuals, may deplete fisheries.[18][21] Contractile cells in each tentacle drag the prey into range of the digestive polyps, the gastrozooids, which surround and digest the food by secreting enzymes that break down proteins, carbohydrates, and fats, while the gonozooids are responsible for reproduction.

Venom

This species is responsible for up to 10,000 human stings in Australia each summer, particularly on the east coast, with some others occurring off the coast of South Australia and Western Australia.[24] One of the problems with identifying these stings is that the detached tentacles may drift for days in the water, and the swimmer may not have any idea if they have been stung by a man o' war or by some other less venomous creature.

The stinging, venom-filled nematocysts in the tentacles of the Portuguese man o' war can paralyze small fish and other prey.[25] Detached tentacles and dead specimens (including those that wash up on shore) can sting just as painfully as the live organism in the water and may remain potent for hours or even days after the death of the organism or the detachment of the tentacle.[26]

Stings usually cause severe pain to humans, leaving whip-like, red welts on the skin that normally last two or three days after the initial sting, though the pain should subside after about 1 to 3 hours (depending on the biology of the person stung). However, the venom can travel to the lymph nodes and may cause symptoms that mimic an allergic reaction including swelling of the larynx, airway blockage, cardiac distress, and an inability to breathe (though this is not due to a true allergy, which is defined by serum IgE). Other symptoms can include fever and shock, and in some extreme cases, even death,[27] although this is extremely rare. Medical attention for those exposed to large numbers of tentacles may become necessary to relieve pain or open airways if the pain becomes excruciating or lasts for more than three hours, or breathing becomes difficult. Instances where the stings completely surround the trunk of a young child are among those that have the potential to be fatal.[28]

Treatment of stings

Stings from a Portuguese man o' war are often extremely painful. They result in severe dermatitis characterized by long, thin, open wounds that resemble those caused by a whip.[29] These are not caused by any impact or cutting action, but by irritating urticariogenic substances in the tentacles.[30][31] Salt water treatment is a myth and should not be used as a treatment.[28][32][33][34]

Acetic acid (vinegar) or a solution of ammonia and water is believed to deactivate the remaining nematocysts and usually provides some pain relief,[28] though some isolated studies suggest that in some individuals vinegar dousing may increase toxin delivery and worsen symptoms.[32][35] Vinegar has also been claimed to provoke hemorrhaging when used on the less severe stings of cnidocytes of smaller species.[36] The current recommended treatment from studies in Australia is to avoid the use of vinegar, as local studies have shown this to exacerbate the symptoms.

The vinegar or ammonia soak is then often followed by the application of shaving cream to the wound for 30 seconds, followed by shaving the area with a razor and rinsing the razor thoroughly between each stroke. This removes any remaining unfired nematocysts. Heat in the form of hot salt water or hot packs may be applied: heat speeds the breakdown of the toxins already in the skin. Hydrocortisone cream may also be used.[28]

Predators and prey

The Portuguese man o' war is a carnivore.[15] Using its venomous tentacles, a man o' war traps and paralyzes its prey while "reeling" it inwards to the digestive polyps. It typically feeds on small marine organisms, such as fish and plankton.

The organism has few predators of its own; one example is the loggerhead turtle, which feeds on the Portuguese man o' war as a common part of its diet.[37] The turtle's skin, including that of its tongue and throat, is too thick for the stings to penetrate.

The blue sea slug Glaucus atlanticus specializes in feeding on the Portuguese man o' war,[38] as does the violet snail Janthina janthina.[39]

The blanket octopus is immune to the venom of the Portuguese man o' war; young individuals carry broken man o' war tentacles, presumably for offensive and/or defensive purposes.[40]

The ocean sunfish's diet, once thought to consist mainly of jellyfish, has been found to include many species, the Portuguese man o' war being one-such example.[41][42]

Commensalism and symbiosis

A small fish, Nomeus gronovii (the man-of-war fish or shepherd fish), is partially immune to the venom from the stinging cells and can live among the tentacles. It seems to avoid the larger, stinging tentacles but feeds on the smaller tentacles beneath the gas bladder. The Portuguese man o' war is often found with a variety of other marine fish, including yellow jack.

All these fish benefit from the shelter from predators provided by the stinging tentacles, and for the Portuguese man o' war, the presence of these species may attract other fish to eat.[43]

See also

- Chondrophores (porpitids), a different hydrozoan colonial organism

- Porpita porpita

- Siphonophorae

References

- Brandt, J. F. 1834-1835. Prodromus descriptionis animalium ab H. Mertensio in orbis terrarum circumnavigatione observatorum. Fascic. I., Polypos, Acalephas Discophoras et Siphonophoras, nec non Echinodermata continens / auctore, Johanne Friderico Brandt. - Recueil Actes des séances publiques de l'Acadadémie impériale des Science de St. Pétersbourg 1834: 201-275., available online at http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/40762#page/5/mode/1up Archived 2019-04-01 at the Wayback Machine page(s): 236

- Lamarck, J. B. (1801). Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou tableau général des classes, des ordres et des genres de ces animaux; Présentant leurs caractères essentiels et leur distribution, d'apres la considération de leurs rapports naturels et de leur organisation, et suivant l'arrangement établi dans les galeries du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle, parmi leurs dépouilles conservées; Précédé du discours d'ouverture du Cours de Zoologie, donné dans le Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle l'an 8 de la République. Published by the author and Deterville, Paris: viii + 432 pp., available online at http://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/14117719 Archived 2017-05-27 at the Wayback Machine page(s): 355

- Schuchert, P. (2019). World Hydrozoa Database. Physaliidae Brandt, 1835. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=135342 Archived 2018-10-27 at the Wayback Machine on 2019-03-11

- Schuchert, P. (2019). World Hydrozoa Database. Physalia Lamarck, 1801. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=135382 Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine on 2019-03-11

- Schuchert, P. (2019). World Hydrozoa Database. Physalia physalis (Linnaeus, 1758). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=135479 Archived 2018-07-27 at the Wayback Machine on 2019-03-11

- "Portuguese man-of-war". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- News, Opening Hours 9 30am-5 00pmMonday- SundayClosed Christmas Day Address 1 William StreetSydney NSW 2010 Australia Phone +61 2 9320 6000 www australianmuseum net au Copyright © 2019 The Australian Museum ABN 85 407 224 698 View Museum. "Bluebottle". The Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 2019-03-17. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- Nick Pisa (27 August 2010). "Woman, 69, DIES after being stung by a Portuguese man-of-war jellyfish while swimming in Sardinia". Mail Online. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Grzimek, B.; Schlager, N.; Olendorf, D. (2003). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopaedia. Thomson Gale. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Greene, Thomas F. Marine Science Textbook.

- Millward, David (8 September 2012). "Surge in number of men o'war being washed up on beaches". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- "Indo-Pacific Portuguese Man-Of-War" (PDF). Marine Life Profile. Waikïkï Aquarium at the University of Hawai‘i-Māno. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-15. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- Clark, F. E.; C. E. Lane (1961). "Composition of float gases of Physalia physalis". Fed. Proc. 107 (3): 673–674. doi:10.3181/00379727-107-26724. PMID 13693830.

- Halstead, B.W. (1988). Poisonous and Venomous Marine Animals of the World. Darwin Press.

- "Portuguese Man-of-War". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- "Dangerous jellyfish wash up". BBC News. 2008-08-18. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2011-09-07./

- "Man-of-war spotted along coast in Cornwall and Wales". BBC. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- Bardi, Juliana; Marques, Antonio C (2007). "Taxonomic redescription of the Portuguese man-of-war, Physalia physalis (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Siphonophorae, Cystonectae) from Brazil" (PDF). Iheringia, Sér. Zool. Brazil: Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul. 97 (4): 425–433. doi:10.1590/S0073-47212007000400011. ISSN 1678-4766. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-29.

- Kozloff, Eugene N. (1990). Invertebrates. Saunders College. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-03-046204-7.

- Wittenberg, Jonathan B. (1960-01-12). "The Source of Carbon Monoxide in the Float of the Portuguese Man-of-War, Physalia physalis L" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 37 (4): 698–705. ISSN 0022-0949. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- Physalia physalis. "Portuguese Man-of-War Printable Page". National Geographic Animals. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2009-05-03. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- "Portuguese Man-of-War (Bluebottle – Physalia spp. – Hydroid)". www.aloha.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- NOAA (27 July 2015). "What is a Portuguese Man o' War?". National Ocean Service. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

Updated 10 October 2017

- Fenner, Peter J.; Williamson, John A. (December 1996). "Worldwide deaths and severe envenomation from jellyfish stings". Medical Journal of Australia. 165 (11–12): 658–661. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb138679.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 8985452.

In Australia, particularly on the east coast, up to 10 000 stings occur each summer from the bluebottle (Physalia spp.) alone, with others also from the "hair jellyfish" (Cyanea) and "blubber" (Catostylus). Common stingers in South Australia and Western Australia, include bluebottle, as well the four-tentacled cubozoa or box jellyfish, the "jimble" (Carybdea rastoni)

- Yanagihara, Angel A.; Kuroiwa, Janelle M.Y.; Oliver, Louise M.; Kunkel, Dennis D. (December 2002). "The ultrastructure of nematocysts from the fishing tentacle of the Hawaiian bluebottle, Physalia utriculus (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Siphonophora)" (PDF). Hydrobiologia. 489 (1–3): 139–150. doi:10.1023/A:1023272519668. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- Auerbach, Paul S. (December 1997). "Envenomations from jellyfish and related species". J Emerg Nurs. 23 (6): 555–565. doi:10.1016/S0099-1767(97)90269-5. PMID 9460392.

- Stein, Mark R.; Marraccini, John V.; Rothschild, Neal E.; Burnett, Joseph W. (March 1989). "Fatal Portuguese man-o'-war (Physalia physalis) envenomation". Ann Emerg Med. 18 (3): 312–315. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(89)80421-4. PMID 2564268.

- Richard A. Clinchy (1996). Dive First Responder. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8016-7525-6. Archived from the original on 2017-02-17. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- "Image Collection: Bites and Infestations: 26. Picture of Portuguese Man of War Sting". www.medicinenet.com. MedicineNet Inc. Archived from the original on 2018-06-03. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

The sting of the Portuguese man-of-war. One of the most painful effects on skin is the consequence of attack by oceanic hydrozoans known as Portuguese men-of-war, which are amazing for their size, brilliant color, and power to induce whealing. They have a small float that buoys them up and from which hang long tentacles. The wrap of these tentacles results in linear stripes, which look like whiplashes, caused not by the force of their sting but from deposition of proteolytic venom toxins, urticariogenic and irritant substances.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; Elston, Dirk M.; Odom, Richard B. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- Slaughter, R.J.; Beasley, D.M.; Lambie, B.S.; Schep, L.J. (2009). "New Zealand's venomous creatures". New Zealand Medical Journal. 122 (1290): 83–97. PMID 19319171. Archived from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- Yoshimoto, C.M.; Yanagihara, A.A. (May–June 2002). "Cnidarian (coelenterate) envenomations in Hawai'i improve following heat application". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 96 (3): 300–303. doi:10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90105-7. PMID 12174784. Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- Loten, Conrad; Stokes, Barrie; Worsley, David; Seymour, Jamie E.; Jiang, Simon; Isbister, Geoffrey K. (3 April 2006). "A randomised controlled trial of hot water (45 °C) immersion versus ice packs for pain relief in bluebottle stings" (PDF). Medical Journal of Australia. 184 (7): 329–333. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00265.x. PMID 16584366. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-03.

- "Ambulance Fact Sheet: Bluebottle Stings" (PDF). www.ambulance.nsw.gov.au. Ambulance Service of New South Wales. July 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-14. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- Exton, D.R. (1988). "Treatment of Physalia physalis envenomation". Medical Journal of Australia. 149 (1): 54. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1988.tb120494.x. PMID 2898725.

- Brodie (1989). Venomous Animals. Western Publishing Company.

- Scocchi, Carla; Wood, James B. "Glaucus atlanticus, Blue Ocean Slug". Thecephalopodpage.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-05. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- Morrison, Sue; Storrie, Ann (1999). Wonders of Western Waters: The Marine Life of South-Western Australia. CALM. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7309-6894-8.

- "Tremoctopus". Tolweb.org. Archived from the original on 2009-07-29. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- Sousa, Lara L.; Xavier, Raquel; Costa, Vânia; Humphries, Nicolas E.; Trueman, Clive; Rosa, Rui; Sims, David W.; Queiroz, Nuno (4 July 2016). "DNA barcoding identifies a cosmopolitan diet in the ocean sunfish". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 28762. doi:10.1038/srep28762. PMC 4931451. PMID 27373803.

- "Portuguese Man o' War", Oceana.org, Oceana, archived from the original on 2017-04-03, retrieved 2017-04-02

- Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Further reading

- Mapstone, Gillian (February 6, 2014). "Global Diversity and Review of Siphonophorae (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa)". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e87737. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987737M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087737. PMC 3916360. PMID 24516560.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Physalia physalis (Portuguese man o' war). |

- Siphonophores.org General information on siphonophores, including the Portuguese man-of-war

- National Geographic: Portuguese Man-of-War

- Life In The Fast Lane: Blue bottle

- PortugueseManOfWar.com