Overactive bladder

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a condition where there is a frequent feeling of needing to urinate to a degree that it negatively affects a person's life.[1] The frequent need to urinate may occur during the day, at night, or both.[5] If there is loss of bladder control then it is known as urge incontinence.[3] More than 40% of people with overactive bladder have incontinence.[2] Conversely, about 40% to 70% of urinary incontinence is due to overactive bladder.[6] Overactive bladder is not life-threatening,[3] but most people with the condition have problems for years.[3]

| Overactive bladder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Overactive bladder syndrome |

| |

| Specialty | Urology |

| Symptoms | Frequent feeling of needing to urinate, incontinence[1][2] |

| Usual onset | More common with age[3] |

| Duration | Often years[3] |

| Causes | Unknown[3] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, caffeine, constipation[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes[1][3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Urinary tract infections, neurological conditions[1][3] |

| Treatment | Pelvic floor exercises, bladder training, drinking moderate fluids, weight loss[4] |

| Prognosis | Not life-threatening[3] |

| Frequency | ~15% men, 25% women[3] |

The cause of overactive bladder is unknown.[3] Risk factors include obesity, caffeine, and constipation.[2] Poorly controlled diabetes, poor functional mobility, and chronic pelvic pain may worsen the symptoms.[3] People often have the symptoms for a long time before seeking treatment and the condition is sometimes identified by caregivers.[3] Diagnosis is based on a person's signs and symptoms and requires other problems such as urinary tract infections or neurological conditions to be excluded.[1][3] The amount of urine passed during each urination is relatively small.[3] Pain while urinating suggests that there is a problem other than overactive bladder.[3]

Specific treatment is not always required.[3] If treatment is desired pelvic floor exercises, bladder training, and other behavioral methods are initially recommended.[4] Weight loss in those who are overweight, decreasing caffeine consumption, and drinking moderate fluids, can also have benefits.[4] Medications, typically of the anti-muscarinic type, are only recommended if other measures are not effective.[4] They are no more effective than behavioral methods; however, they are associated with side effects, particularly in older people.[4][7] Some non-invasive electrical stimulation methods appear effective while they are in use.[8] Injections of botulinum toxin into the bladder is another option.[4] Urinary catheters or surgery are generally not recommended.[4] A diary to track problems can help determine whether treatments are working.[4]

Overactive bladder is estimated to occur in 7-27% of men and 9-43% of women.[3] It becomes more common with age.[3] Some studies suggest that the condition is more common in women, especially when associated with loss of bladder control.[3] Economic costs of overactive bladder were estimated in the United States at US$12.6 billion and 4.2 billion Euro in 2000.[9]

Signs and symptoms

Overactive bladder is characterized by a group of four symptoms: urgency, urinary frequency, nocturia, and urge incontinence. Urge incontinence is not present in the "dry" classification.

Urgency is considered the hallmark symptom of OAB, but there are no clear criteria for what constitutes urgency and studies often use other criteria.[3] Urgency is currently defined by the International Continence Society (ICS), as of 2002, as "Sudden, compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer." The previous definition was "Strong desire to void accompanied by fear of leakage or pain."[10] The definition does not address the immediacy of the urge to void and has been criticized as subjective.[10]

Urinary frequency is considered abnormal if the person urinates more than eight times in a day. This frequency is usually monitored by having the patient keep a voiding diary where they record urination episodes.[3] The number of episodes varies depending on sleep, fluid intake, medications, and up to seven is considered normal if consistent with the other factors.

Nocturia is a symptom where the person complains of interrupted sleep because of an urge to void and, like the urinary frequency component, is affected by similar lifestyle and medical factors. Individual waking events are not considered abnormal, one study in Finland established two or more voids per night as affecting quality of life.[11]

Urge incontinence is a form of urinary incontinence characterized by the involuntary loss of urine occurring for no apparent reason while feeling urinary urgency as discussed above. Like frequency, the person can track incontinence in a diary to assist with diagnosis and management of symptoms. Urge incontinence can also be measured with pad tests, and these are often used for research purposes. Some people with urge incontinence also have stress incontinence and this can complicate clinical studies.[3]

It is important that the clinician and the patient both reach a consensus on the term, 'urgency.' Some common phrases used to describe OAB include, 'When I've got to go, I've got to go,' or 'When I have to go, I have to rush, because I think I will wet myself.' Hence the term, 'fear of leakage,' is an important concept to patients.[12]

Causes

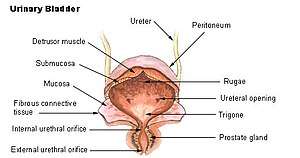

The cause of OAB is unclear, and indeed there may be multiple causes.[13] It is often associated with overactivity of the detrusor urinae muscle, a pattern of bladder muscle contraction observed during urodynamics.[14] It is also possible that the increased contractile nature originates from within the urothelium and lamina propria, and abnormal contractions in this tissue could stimulate dysfunction in the detrusor or whole bladder.[15]

Catheter-related irritation

If bladder spasms occur or there is no urine in the drainage bag when a catheter is in place, the catheter may be blocked by blood, thick sediment, or a kink in the catheter or drainage tubing. Sometimes spasms are caused by the catheter irritating the bladder, prostate or penis. Such spasms can be controlled with medication such as butylscopolamine, although most patients eventually adjust to the irritation and the spasms go away.[16]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of OAB is made primarily on the person's signs and symptoms and by ruling out other possible causes such as an infection.[3] Urodynamics, a bladder scope, and ultrasound are generally not needed.[3][17] Additionally, urine culture may be done to rule out infection. The frequency/volume chart may be maintained and cystourethroscopy may be done to exclude tumor and kidney stones. If there is an underlying metabolic or pathologic condition that explains the symptoms, the symptoms may be considered part of that disease and not OAB.

Psychometrically robust self-completion questionnaires are generally recognized as a valid way of measuring a person's signs and symptoms, but there does not exist a single ideal questionnaire.[18] These surveys can be divided into two groups: general surveys of lower urinary tract symptoms and surveys specific to overactive bladder. General questionnaires include: American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUASI), Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI),[19] Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ),[19] and Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (BFLUTS). Overactive bladder questionnaires include: Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB-q),[20] Urgency Questionnaire (UQ), Primary OAB Symptom Questionnaire (POSQ), and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ).

OAB causes similar symptoms to some other conditions such as urinary tract infection (UTI), bladder cancer, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Urinary tract infections often involve pain and hematuria (blood in the urine) which are typically absent in OAB. Bladder cancer usually includes hematuria and can include pain, both not associated with OAB, and the common symptoms of OAB (urgency, frequency, and nocturia) may be absent. BPH frequently includes symptoms at the time of voiding as well as sometimes including pain or hematuria, and all of these are not usually present in OAB.[10] Diabetes insipidus, which causes high frequency and volume, though not necessarily urgency.

Classification

There is some controversy about the classification and diagnosis of OAB.[3][21] Some sources classify overactive bladder into two different variants: "wet" (i.e., an urgent need to urinate with involuntary leakage) or "dry" (i.e., an urgent need to urinate but no involuntary leakage). Wet variants are more common than dry variants.[22] The distinction is not absolute; one study suggested that many classified as "dry" were actually "wet" and that patients with no history of any leakage may have had other syndromes.[23]

OAB is distinct from stress urinary incontinence, but when they occur together, the condition is usually known as mixed incontinence.

Management

Lifestyle

Treatment for OAB includes nonpharmacologic methods such as lifestyle modification (fluid restriction, avoidance of caffeine), bladder retraining, and pelvic floor muscle (PFM) exercise.

Timed voiding is a form of bladder training that uses biofeedback to reduce the frequency of accidents resulting from poor bladder control. This method is aimed at improving the person's control over the time, place and frequency of urination.

Timed voiding programs involve establishing a schedule for urination. To do this a patient fills in a chart of voiding and leaking. From the patterns that appear in the chart, the patient can plan to empty his or her bladder before he or she would otherwise leak. Some individuals find it helpful to use a vibrating reminder watch to help them remember to use the bathroom. Vibrating watches can be set to go off at certain intervals or at specific times throughout the day, depending on the watch.[24] Through this bladder training exercise, the patient can alter their bladder's schedule for storing and emptying urine.[25]

Medications

A number of antimuscarinic drugs (e.g., darifenacin, hyoscyamine, oxybutynin, tolterodine, solifenacin, trospium, fesoterodine) are frequently used to treat overactive bladder.[14] Long term use, however, has been linked to dementia.[26] β3 adrenergic receptor agonists (e.g., mirabegron),[27] may be used, as well. However, both antimuscarinic drugs and β3 adrenergic receptor agonists constitute a second line treatment due to the risk of side effects.[3]

Few people get complete relief with medications and all medications are no more than moderately effective.[28]

A typical person with overactive bladder may urinate 12 times per day.[28] Medication may reduce this number by 2-3 and reduce urinary incontinence events by 1-2 per day.[28]

Procedures

Various devices (Urgent PC Neuromodulation System) may also be used. Botulinum toxin A (Botox) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration in adults with neurological conditions, including multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury.[29] Botulinum Toxin A injections into the bladder wall can suppress involuntary bladder contractions by blocking nerve signals and may be effective for up to 9 months.[30][31] The growing knowledge of pathophysiology of overactive bladder fuelled a huge amount of basic and clinical research in this field of pharmacotherapy.[32][33][34] A surgical intervention involves the enlargement of the bladder using bowel tissues, although generally used as a last resort. This procedure can greatly enlarge urine volume in the bladder.

OAB may be treated with electrical stimulation, which aims to reduce the contractions of the muscle that tenses around the bladder and causes urine to pass out of it. There are invasive and non-invasive electrical stimulation options. Non-invasive options include the introduction of a probe into the vagina or anus, or the insertion of an electrical probe into a nerve near the ankle with a fine needle. These non-invasive options appear to reduce symptoms while they are in use, and are better than no treatment, or treatment with drugs, or pelvic floor muscle treatment, but the quality of evidence is low. It is unknown which electrical stimulation option works best. Also, it is unknown whether the benefits last after treatment stops.[8]

Prognosis

Many people with OAB symptoms had those symptoms subside within a year, with estimates as high as 39%, but most have symptoms for several years.[3]

Epidemiology

Earlier reports estimated that about one in six adults in the United States and Europe had OAB.[35][36] The prevalence of OAB increases with age,[35][36] thus it is expected that OAB will become more common in the future as the average age of people living in the developed world is increasing. However, a recent Finnish population-based survey[37] suggested that the prevalence had been largely overestimated due to methodological shortcomings regarding age distribution and low participation (in earlier reports). It is suspected, then, that OAB affects approximately half the number of individuals as earlier reported.[37]

The American Urological Association reports studies showing rates as low as 7% to as high as 27% in men and rates as low as 9% to 43% in women.[3] Urge incontinence was reported as higher in women.[3] Older people are more likely to be affected, and prevalence of symptoms increases with age.[3]

See also

- National Association For Continence

- Underactive bladder

References

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP (May 2015). "Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment". The Journal of Urology. 193 (5): 1572–80. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.087. PMID 25623739.

- Gibbs, Ronald S. (2008). Danforth's obstetrics and gynecology (10 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 890–891. ISBN 9780781769372. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- American Urological Association (2014). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Overactive Bladder (Non-Neurogenic) in Adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, Chai TC, Clemens JQ, Culkin DJ, Das AK, Foster HE, Scarpero HM, Tessier CD, Vasavada SP (December 2012). "Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline". The Journal of Urology. 188 (6 Suppl): 2455–63. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.079. PMID 23098785.

- "Urinary Bladder, Overactive". Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Ghosh, Amit K. (2008). Mayo Clinic internal medicine concise textbook. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press. p. 339. ISBN 9781420067514. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- Ruxton K, Woodman RJ, Mangoni AA (August 2015). "Drugs with anticholinergic effects and cognitive impairment, falls and all-cause mortality in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 80 (2): 209–20. doi:10.1111/bcp.12617. PMC 4541969. PMID 25735839.

- Stewart F, Gameiro LF, El Dib R, Gameiro MO, Kapoor A, Amaro JL (December 2016). "Electrical stimulation with non-implanted electrodes for overactive bladder in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD010098. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010098.pub4. hdl:2164/8446. PMC 6463833. PMID 27935011.

- Abrams, Paul (2011). Overactive bladder syndrome and urinary incontinence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780199599394. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- Wein A (October 2011). "Symptom-based diagnosis of overactive bladder: an overview". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 5 (5 Suppl 2): S135–6. doi:10.5489/cuaj.11183. PMC 3193392. PMID 21989525.

- Tikkinen KA, Johnson TM, Tammela TL, Sintonen H, Haukka J, Huhtala H, Auvinen A (March 2010). "Nocturia frequency, bother, and quality of life: how often is too often? A population-based study in Finland". European Urology. 57 (3): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.080. PMID 19361907.

- Campbell-Walsh Urology, Tenth Edition, Chapter 66, Page 1948

- Sacco E (2012). "[Physiopathology of overactive bladder syndrome]". Urologia. 79 (1): 24–35. doi:10.5301/RU.2012.8972. PMID 22287269.

- Sussman DO (September 2007). "Overactive bladder: treatment options in primary care medicine". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 107 (9): 379–85. PMID 17908830.

- Moro C, Uchiyama J, Chess-Williams R (December 2011). "Urothelial/lamina propria spontaneous activity and the role of M3 muscarinic receptors in mediating rate responses to stretch and carbachol". Urology. 78 (6): 1442.e9–15. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.039. PMID 22001099.

- "Urinary catheters". MedlinePlus, the National Institutes of Health's Web site. 2010-03-09. Archived from the original on 2010-12-04. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- American Urogynecologic Society (May 5, 2015), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Urogynecologic Society, archived from the original on June 2, 2015, retrieved June 1, 2015

- Shy M, Fletcher SG (March 2013). "Objective Evaluation of Overactive Bladder: Which Surveys Should I Use?". Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports. 8 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1007/s11884-012-0167-2. PMC 3579666. PMID 23439804.

- Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, McClish D, Fantl JA (October 1994). "Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group". Quality of Life Research. 3 (5): 291–306. doi:10.1007/bf00451721. PMID 7841963.

- Coyne K, Schmier J, Hunt T, Corey R, Liberman J, Revicki D (March 2000). "PRN6: developing a specific HRQL instrument for overactive bladder". Value in Health. 3 (2): 141. doi:10.1016/s1098-3015(11)70554-x.

- Homma Y (January 2008). "Lower urinary tract symptomatology: Its definition and confusion". International Journal of Urology. 15 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01907.x. PMID 18184169.

- "Overactive Bladder". Cornell University Weill Cornell Medical College Department of Urology. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 25 Aug 2013.

- Anger JT, Le TX, Nissim HA, Rogo-Gupta L, Rashid R, Behniwal A, Smith AL, Litwin MS, Rodriguez LV, Wein AJ, Maliski SL (November 2012). "How dry is "OAB-dry"? Perspectives from patients and physician experts". The Journal of Urology. 188 (5): 1811–5. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.044. PMC 3571660. PMID 22999694.

- Pham, Nancy. "Get Control Over Your Bladder with a Vibrating Reminder". National Incontinence. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Mercer, Renee. "Strategies to Control Incontinence". National Incontinence. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- Araklitis G, Cardozo L (November 2017). "Safety issues associated with using medication to treat overactive bladder". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 16 (11): 1273–1280. doi:10.1080/14740338.2017.1376646. PMID 28889761.

- Sacco E, Bientinesi R (December 2012). "Mirabegron: a review of recent data and its prospects in the management of overactive bladder". Therapeutic Advances in Urology. 4 (6): 315–24. doi:10.1177/1756287212457114. PMC 3491758. PMID 23205058.

- Consumer Reports Health Best Buy Drugs (June 2010). "Evaluating Prescription Drugs to Treat: Overactive Bladder - Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price". Best Buy Drugs: 10. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2012., which cites "Overactive Bladder Drugs". Drug Effectiveness Review Project. Oregon Health & Science University. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- "FDA approves Botox for loss of bladder control". Reuters. 24 August 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Chancellor, Michael B; Christopher Smith (August 2011). Botulinum Toxin in Urology. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-03579-1.

- Sacco E, Paolillo M, Totaro A, Pinto F, Volpe A, Gardi M, Bassi PF (2008). "Botulinum toxin in the treatment of overactive bladder". Urologia. 75 (1): 4–13. doi:10.1177/039156030807500102. PMID 21086369.

- Sacco E, Bientinesi R (2012). "Future perspectives in pharmacological treatments options for overactive bladder syndrome". Eur Urol Review. 7 (2): 120–126.

- Sacco E, Pinto F, Bassi P (April 2008). "Emerging pharmacological targets in overactive bladder therapy: experimental and clinical evidences". International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 19 (4): 583–98. doi:10.1007/s00192-007-0529-z. PMID 18196198.

- Sacco E, et al. (2009). "Investigational drug therapies for overactive bladder syndrome: the potential alternatives to anticholinergics". Urologia. 76 (3): 161–177. doi:10.1177/039156030907600301.

- Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, Abrams P, Herzog AR, Corey R, Hunt TL, Wein AJ (May 2003). "Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States". World Journal of Urology. 20 (6): 327–36. doi:10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4. PMID 12811491.

- Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, Roberts RG, Thüroff J, Wein AJ (June 2001). "How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study". BJU International. 87 (9): 760–6. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02228.x. PMID 11412210.

- Tikkinen KA, Tammela TL, Rissanen AM, Valpas A, Huhtala H, Auvinen A (February 2007). Madersbacher S (ed.). "Is the prevalence of overactive bladder overestimated? A population-based study in Finland". PLOS ONE. 2 (2): e195. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000195. PMC 1805814. PMID 17332843.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Sacco E, Bientinesi R, Marangi F, D'Addessi A, Racioppi M, Gulino G, Pinto F, Totaro A, Bassi P (2011). "[Overactive bladder syndrome: the social and economic perspective]". Urologia (in Italian). 78 (4): 241–56. doi:10.5301/RU.2011.8886. PMID 22237808.