Cystoscopy

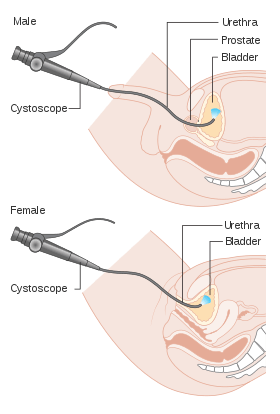

Cystoscopy is endoscopy of the urinary bladder via the urethra. It is carried out with a cystoscope.

| Cystoscopy | |

|---|---|

Diagram showing a cystoscopy for a male and a female | |

| Pronunciation | si-ˈstäs-kə-pē |

| ICD-9-CM | 57.31-57.33 |

| MeSH | D003558 |

| MedlinePlus | 003903 |

The urethra is the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body. The cystoscope has lenses like a telescope or microscope. These lenses let the physician focus on the inner surfaces of the urinary tract. Some cystoscopes use optical fibres (flexible glass fibres) that carry an image from the tip of the instrument to a viewing piece at the other end. Cystoscopes range from pediatric to adult and from the thickness of a pencil up to approximately 9 mm and have a light at the tip. Many cystoscopes have extra tubes to guide other instruments for surgical procedures to treat urinary problems.

There are two main types of cystoscopy—flexible and rigid—differing in the flexibility of the cystoscope. Flexible cystoscopy is carried out with local anaesthesia on both sexes. Typically, a topical anesthetic, most often xylocaine gel (common brand names are Anestacon and Instillagel) is employed. The medication is instilled into the urethra via the urinary meatus five to ten minutes prior to the beginning of the procedure. Rigid cystoscopy can be performed under the same conditions, but is generally carried out under general anesthesia, particularly in male subjects, due to the pain caused by the probe. The sizes of the sheath of the rigid cystoscope are 17 French gauge (5.7 mm diameter), 19 Fr gauge (6.3 mm diameter), and 22 Fr gauge (7.3 mm diameter).

Medical uses

Cystoscopy may be recommended for any of the following conditions:[1]

- urinary tract infections;

- blood in the urine (hematuria);

- loss of bladder control (incontinence) or overactive bladder; (Although, the American Urogynecologic Society does not recommend that cystoscopy, urodynamics, or diagnostic renal and bladder ultrasound are part of initial diagnosis for uncomplicated overactive bladder.)[2][3]

- unusual cells found in urine sample;

- need for a bladder catheter;

- painful urination, chronic pelvic pain, or interstitial cystitis;

- urinary blockage such as from prostate enlargement, stricture, or narrowing of the urinary tract;

- stone in the urinary tract; and

- unusual growth, polyp, tumor, or cancer.

Male and female urinary tracts

If a patient has a stone lodged higher in the urinary tract, the physician may use a much finer calibre scope called a ureteroscope through the bladder and up into the ureter. (The ureter is the tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder.) The physician can then see the stone and remove it with a small basket at the end of a wire that is inserted through an extra tube in the ureteroscope. For larger stones, the physician may also use the extra tube in the ureteroscope to extend a flexible fiber that carries a laser beam to break the stone into smaller pieces that can then pass out of the body in the urine.

Test procedures

Physicians may have special instructions, but in most cases, patients are able to eat normally and return to normal activities after the test. Patients are sometimes asked to give a urine sample before the test to check for infection. These patients should ensure that they do not urinate for a sufficient period of time, such that they are able to urinate prior to this part of the test.

Patients will have to remove their clothing covering the lower part of the body, although some physicians may prefer if the patient wears a hospital gown for the examination and covers the lower part of the body with a sterile drape. In most cases, patients lie on their backs with their knees slightly parted. Occasionally, a patient may also need to have his or her knees raised. This is particularly true when undergoing a Rigid Cystoscopy examination. For flexible cystoscopy procedures the patient is almost always alert and a local anesthetic is applied to reduce discomfort. In cases requiring a rigid cystoscopy it is not unusual for the patient to be given a general anesthetic, as these can be more uncomfortable, particularly for men. A physician, nurse, or technician will clean the area around the urethral opening and apply a local anesthetic. The local anesthetic is applied direct from a tube or needleless syringe into the urinary tract. Often, skin preparation is performed with chlorhexidine.[4]

Patients receiving a ureteroscopy may receive a spinal or general anaesthetic.

The physician will gently insert the tip of the cystoscope into the urethra and slowly glide it up into the bladder. The procedure is more painful for men than for women due to the length and narrow diameter of the male urethra. Relaxing the pelvic muscles helps make this part of the test easier. A sterile liquid (water, saline, or glycine solution) will flow through the cystoscope to slowly fill the bladder and stretch it so that the physician has a better view of the bladder wall.

As the bladder reaches capacity, patients typically feel some mild discomfort and the urge to urinate.

The time from insertion of the cystoscope to removal may be only a few minutes, or it may be longer if the physician finds a stone and decides to remove it, or in cases where a biopsy is required. Taking a biopsy (a small tissue sample for examination under a microscope) will also make the procedure last longer. In most cases, the entire examination, including preparation, will take about 15 to 20 minutes.

Blue light

In blue light cystoscopy hexyl aminolevulinate hydrochloride is instilling a photosensitizing agent, into the bladder. The blue light cystoscopy contains a light source and light is transmitted through a fluid light cable connected to an endoscope to light up the area to be observed. The photosensitizing agent preferentially accumulates porphyrins in malignant cells as opposed to nonmalignant cells of urothelial origin. Under subsequent blue light illumination, neoplastic lesions fluoresce red, enabling visualization of tumors. The blue light cystoscopy is used to detect non-muscle invasive papillary cancer of the bladder.[5][6]

Post-procedural care

After the test, patients often have some burning feeling when they urinate and often see small amounts of blood in their urine. Procedures using rigid instrumentation often result in urinary incontinence and leakage from idiopathic causes to urethral damage. Occasionally, patients may feel some lower abdominal pains, reflecting bladder muscle spasms, but these are not common.

Common (non-invasive) prescriptions to relieve discomfort after the test may include:

- drinking 32 fluid ounces (1 L) of water over 2 hours;

- taking a warm bath to relieve the burning feeling; and

- holding a warm, damp washcloth over the urethral opening.

Prior to the early 1990s, it was common practice for the physician performing the procedure to prescribe an antibiotic to take for a few days to prevent an infection. Since that time, many urologists will order a "urine C & S" (urinalysis with bacterial/fungal cultures and testing for sensitivities to anti-infective medications) prior to the performance of the cystoscopy, and as part of the pre-operative workup. Depending on the results of the testing and other circumstances, he or she may elect to prescribe a 10- to 14-day course of antibiotic or other anti-infective treatment, commencing 3 days before the cystoscopy is to be performed, as this may alleviate some inflammation of the urethra prior to the procedure. This practice may provide an additional benefit by preventing an accidental infection from occurring during the procedure. The full-course of antibiotic treatment also lessens the possibility of the bacteria becoming resistant to the antibiotic/anti-infective agent prescribed.

Physicians may also prescribe an oral urinary analgesic, phenazopyridine, or a combination (urinary) analgesic/anti-infective/anti-spasmodic medication containing methylene blue, methanamine, hyoscyamine sulfate and phenyl salicylate for irritation and/or dysuria patients may experience after the procedure. At two weeks post-procedure, the practitioner may order a follow-up evaluation including a repeat of the urinalysis with cultures and sensitivities, and a uroflowmetric study (which evaluates the volume of urine released from the body, the speed with which it is released, and how long the release takes).

Other animals

Cystoscopy has similar indications in animals, including visualisation and biopsy of mucosa, retrieval or destruction of urinary bladder stones and diagnosis of ectopic ureters.[7][8][9]

In turtle and tortoises, cystoscopy has additional value as it permits the visualisation of internal organs due to the thin urinary bladder wall.[10] In young individuals in which sex determination would not be feasible by visualisation of external morphologic features, this technique permits noninvasive visualisation of gonads, and therefore sex determination.[11]

References

- Cystoscopy and Ureteroscopy – The Doctors Lounge (TM)

- American Urogynecologic Society (May 5, 2015). "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American Urogynecologic Society. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- Gormley, EA; Lightner, DJ; Faraday, M; Vasavada, SP (May 2015). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Overactive Bladder (Non-Neurogenic) in Adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline Amendment". The Journal of Urology. 193 (5): 1572–80. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.087. PMID 25623739.

- "Pharmaceutical Information – Hibitane". RxMed. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- FDA Photodynamic Diagnostic D-Light C (PDD) System – P050027

- "Blue light cystoscopy for detection and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

- Morgan M, Forman M. "Cystoscopy in dogs and cats". Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2015 Jul;45(4):665–701. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2015.02.010. Review.

- Childress MO, Adams LG, Ramos-Vara JA, Freeman LJ, He S, Constable PD, Knapp DW. "Results of biopsy via transurethral cystoscopy and cystotomy for diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder and urethra in dogs: 92 cases (2003–2008)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011 Aug 1;239(3):350–6. doi:10.2460/javma.239.3.350.

- Smith AL, Radlinsky MG, Rawlings CA. "Cystoscopic diagnosis and treatment of ectopic ureters in female dogs: 16 cases (2005–2008)", J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2010 Jul 15;237(2):191–5. doi:10.2460/javma.237.2.191

- Di Girolamo N, Selleri P. "Clinical Applications of Cystoscopy in Chelonians". Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2015 Sep;18(3):507–26. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2015.04.008.

- Selleri P, Di Girolamo N, Melidone R. "Cystoscopic sex identification of posthatchling chelonians". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013 Jun 15;242(12):1744–50. doi:10.2460/javma.242.12.1744.

- An earlier version of this article was adapted from the public domain NIH Publication No. 01-4800, which says, "This e-text is not copyrighted. The clearinghouse encourages users of this e-pub to duplicate and distribute as many copies as desired."