Maternal mortality in the United States

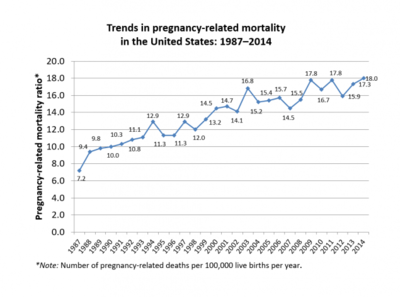

Maternal mortality refers to the death of a woman during her pregnancy or up to a year after her pregnancy has terminated; this only includes causes related to her pregnancy and does not include accidental causes.[1] Some sources will define maternal mortality as the death of a woman up to 42 days after her pregnancy has ended, instead of one year.[2] In 1986, the CDC began tracking pregnancy related deaths to gather information and determine what was causing these deaths by creating the Pregnancy-Related Mortality Surveillance System.[1] Although the United States was spending more on healthcare than any other country in the world, more than two women died during childbirth every day, making maternal mortality in the United States the highest when compared to 49 other countries in the developed world.[3] The CDC reported an increase in the maternal mortality ratio in the United States from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 births to 23.8 deaths per 100,000 births between 2000 and 2014, a 26.6% increase;[4] It is estimated that 20-50% of these deaths are due to preventable causes, such as: hemorrhage, severe high blood pressure, and infection.[5]

Monitoring maternal mortality

In 1986, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) created the Pregnancy-Related Mortality Surveillance System to monitor maternal deaths during pregnancy and up to one year after giving birth. Prior to this, women were monitored up to 6 weeks postpartum.[1]

In 2016 the CDC Foundation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs (AMCHP) undertook a collaborative initiative—"Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths"— funded by Merck under the Merck for Mothers program. They are reviewing maternal mortality to enhance understanding of the increase in the maternal mortality ratio in the United States, and to identify preventative interventions.[6] Through this initiative, they have created Review to Action website which hosts their reports and resources. In their 2017 report, four states, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, and Ohio, supported the development of the Maternal Mortality Review Data System (MMRDS) which was intended as a precursor to the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application (MMRIA).[7] The three agencies have partnered with Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina, and Utah to collect data for the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application (MMRIA); the nine states submitted their first reports in 2018.[8]

After decades of inaction on the part of the U.S. Congress towards reducing the maternal mortality ratio, the United States Senate Committee on Appropriations voted on June 28, 2018 to request $50 million to prevent the pregnancy-related deaths of American women.[9] The CDC would receive $12 million for research and data collection. They would also support individual states in counting and reviewing data on maternal deaths.[9] The federal Maternal and Child Health Bureau would receive the remaining $38 million directed towards Healthy Start program and "life saving, evidence-based programs" at hospitals.[9] MCHB's Healthy Start was mandated to reduce the infant mortality rate.[10]

Measurement and data collection

According to a 2016 article in Obstetrics and Gynecology by MacDorman et al., one factor affecting the US maternal death rate is the variability in calculation of maternal deaths. The WHO deems maternal deaths to be those occurring within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, whereas the United States Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System measures maternal deaths as those occurring within a year of the end of pregnancy.[4] Some states allow multiple responses, such as whether death occurred during pregnancy, within 42 days after pregnancy, or within a year of pregnancy, but some states, such as California, ask simply whether death occurred within a year postpartum.[4]

In their article, the authors described how data collection on maternal mortality rates became an "international embarrassment".[4][11]:427 In 2003 the national U.S. standard death certificate added a "tick box" question regarding the pregnancy status of the deceased. Many states delayed adopting the new death certificate standards. This "muddied" data and obstructed analysis of trends in maternal mortality rates. It also meant that for many years, the United States could not report a national maternal mortality rate to the OECD or other repositories that collect data internationally.[4][11]:427

In response to the MacDorman study, revealing the "inability, or unwillingness, of states and the federal government to track maternal deaths",[12] ProPublica and NPR found that in 2016 alone, between 700 and 900 women died from pregnancy- and childbirth-related causes. In "Lost Mothers" they published stories of some of women who died. They ranged in age from 16 to 43.[12]

Healthy People is a federal organization that is managed by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). In 2010, the US maternal mortality ratio was 12.7 (deaths per 100,000 live births). This was 3 times as high as the Healthy People 2010 goal, a national target set by the US government.[13]

According to a 2009 article in Anthropology News, studies conducted by but not limited to Amnesty International, the United Nations, and federal programs such as the CDC, maternal mortality has not decreased since 1999 and may have been rising.[14]

By November 2017, Baltimore and Philadelphia, and New York City had established committees to "review deaths and severe complications related to pregnancy and childbirth" in their cities to prevent maternal mortality. New York's panel, the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee (M3RC) doctors, nurses, "doulas, midwives and social workers".[15] New York City will be collaborating with the State of New York, the first such collaboration in the US.[15] In July 2018, New York City's de Blasio's administration announced that it would be allocating $12.8 million for the first three years of its five-year plan to "reduce maternal deaths and life-threatening complications of childbirth among women of color".[16]

Causes

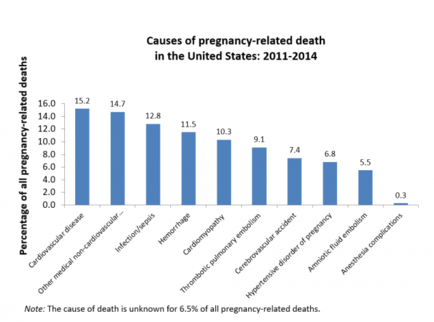

Medical causes

Maternal death can be traced to maternal health, which includes wellness throughout the entire pregnancy and access to basic care.[17] More than half of maternal deaths occur within the first 42 days after birth. Race, location, and financial status all contribute to how maternal mortality affects women across the country.

In response to the high maternal mortality ratio in Texas, in 2013 the Department of State created the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force. According to Amnesty International's 2010 report, five medical conditions collectively account for 74% of maternal deaths in the US.

- Embolism: blood vessels blocked likely due to deep vein thrombosis, a blood clot that forms in a deep vein, commonly in the legs but could be from other deep veins.* Pulmonary embolisms and strokes are blockages in the lungs and brain respectively and are severe, could lead to long term effects, or be fatal.

- Hemorrhage: severe bleeding. Hemorrhages can be caused by placenta accreta, increta, and percreta, uterine rupture, ectopic pregnancy, uterine atony, retained products of conception, and tearing. During labor, it is common to lose between half a quart to a quart depending on whether a mother delivers naturally or by cesarean section. With the additional and severe amount of bleeding due to hemorrhage, the mother’s internal organs could go into shock due to poor blood flow which is fatal.

- Pre-eclampsia: at about 20 weeks until after delivery, pregnant women could have an increase in blood pressure which could indicate pre-eclampsia. Pre-eclampsia involves the liver and kidneys not working properly which is indicated by protein in the urine as well as having hypertension. Pre-eclampsia can also become eclampsia, the mother seizes or is in a coma, which is rare but fatal.

- Infection: each person has a different immune system, when a woman is pregnant, their immune systems behaves different than originally causing increased susceptibility to infection which can be threatening to both mother and baby. Different types of infection include, infection of amniotic fluid and surrounding tissues, influenza, genital tract infections, and sepsis/blood infection. Fever, chills, abnormal heart rate, and breathing rate can indicate some form of infection.

- Cardiomyopathy[18]: the enlargement of heart, increased thickness, and possible rigidness which causes the heart to weaken and die. This may lead to low blood pressure, reduced heart function, and heart failure. Other cardiovascular disorders are contributory to maternal mortality as well.

Postpartum depression is widely untreated and unrecognized, leading to suicide. Suicide is one of the most significant causes of maternal mortality,[18][19] and reported to be the number one cause by many studies.[20] Postpartum depression is caused by a chemical imbalance due to the hormonal changes during and after birth and is more long term and severe than “baby blues.”

Social factors

Social determinants of health also contribute to the maternal mortality rate. Some of these factors include access to healthcare, education, age, race, and income.[21]

Access to healthcare

Pregnant people in the US usually meet with their physicians just once after delivery, six weeks after giving birth. Due to this long gap during the postpartum period, many health problems remain unchecked, which can result in maternal death.[22] Just as pregnant people, especially pregnant people of color, have difficulty with access to prenatal care, the same is true for accessibility to postpartum care. Also, postpartum depression can also lead to untimely deaths for both mother and child.[23]

Maternal-fetal medicine does not require labor-delivery training in order to practice independently.[24] The lack of experience can make certain doctors more likely to make mistakes or not pay close attention to certain symptoms that could indicate one of the several causes of death in mothers. For pregnant people who have limited access, these kinds of physicians may be easier to see than more experienced physicians. In addition, many doctors are unwilling to see patients who are pregnant if they are uninsured or unable to afford their co-pay, which restricts prenatal care and could prevent pregnant people from being unaware of potential complications.

Insurance companies reserve the right to categorize pregnancy as a pre-existing condition, thereby making pregnant people ineligible for private health insurance. Even access to Medicaid is curtailed to some pregnant people, due to bureaucracy and delays in coverage (if approved). Many pregnant people are turned down due to Medicaid fees, as well. Medicaid also does not cover doula care for pregnant people during their prenatal or post-partum period. Doulas provide non-medical, physical, emotional and informational support to pregnant people before, during and immediately following childbirth.[25] The supportive care practice of a doula has potential to improve the health of both the mother and child, and reduce health disparities.[26] Doula care provided to pregnant people most at risk of poor maternal health outcomes can reduce disparities by improving the health and care of those who are most in need. Pregnant people with the worst maternal health outcomes in the United States are people of color that live in high-poverty areas, whose access to doula support may be extremely limited. Doula services are underutilized especially in low-income communities of color.[27] Pregnant people within these communities face barriers that limit their access to services, they lack the information about available services and they are faced with a cost they cannot afford.[28] “A national survey found that pregnant people whose delivery was covered by Medicaid were almost 50% less likely to know about doula care than pregnant people who were privately insured”.[29] Pregnant people have also reported access and mobility as reasons why they are unable to seek prenatal care, such as lack of transportation and/or lack of health insurance. pregnant people who do not have access to prenatal care are 3-4 times more likely to die during or after pregnancy than people who do.[30]

Education

It has been shown that mothers between ages 18 and 44 who did not complete high school had a 5% increase in maternal mortality versus women who completed high school.[31] By completing primary school, 10% of girls younger than 17 years old would not get pregnant and 2/3 of maternal deaths could be prevented.[32] Secondary education, university schooling, would only further decrease rates of pregnancy and maternal death.

Age

Young adolescents are at the highest risk of fatal complications of any age group [33] .

Race

African American women are four times as likely to suffer from maternal morbidity and mortality than Caucasian women,[3] and there has been no large-scale improvement over the course of 20 years to rectify these conditions.[34] Furthermore, women of color, especially "African-American, Indigenous, Latina and immigrant women and women who did not speak English", are less likely to obtain the care they need. In addition, foreign-born women have an increased likelihood of maternal mortality, particularly Hispanic Women.[35] Cause of mortality, especially in older women, is different among different races. Caucasian women are more likely to experience hemorrhage, cardiomyopathy, and embolism whereas African American women are more likely to experience hypertensive disorders, stroke, and infection.

The US has shown to have the highest rate of pregnancy related deaths o/c maternal mortality amongst all the industrialized countries. The CDC first implemented the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System in 1986 and since then maternal mortality rates have increased from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 17.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015. The issue of maternal mortality disproportionately affects women of colour when compared with the rate in white non-Hispanic women. The following statistics were retrieved from the CDC and show the rate of maternal mortality between 2011 and 2015 per 100000 live births: Black non-Hispanic -42.8, American Indian/Alaskan Native non-Hispanic-32.5, Asian/Pacific Islander on-Hispanic -14.2, White non-Hispanic-13.0, and Hispanic -11.4. Black non-Hispanic women tend to have limited access to pre- and post-natal healthcare services. Additionally, they experience higher rates of discrimination, disrespect and abuse than white non-Hispanic women.

Income

Studies have shown that women are affected by the stress of being lower income, which then affects their pregnancies and unborn babies. In the US, women of color disproportionately experience stress related to financial burdens and perceived racism when trying to gain access to healthcare. These women have a harder time maintaining or gaining access to healthy nutrition and even safe housing. These social factors are directly linked to the outcome of maternal care.[citation needed]

It is estimated that 99% of women give birth in hospitals with fees that average between $8,900-$11,400 for vaginal delivery, and between $14,900-$20,100 for a cesarean.[36] Many women cannot afford these high costs, nor can they afford private health insurance, and even waiting on government-funded care can prove to be fatal, since delays to coverage usually result in women not getting the care they need from the start.

Other risk factors

Some other risk factors include obesity, chronic high blood pressure, increased age, diabetes, cesarean delivery, and smoking. Attending less than 10 prenatal visits is also associated with a higher risk of maternal mortality.[31]

The Healthy People 2010 goal was to reduce the c-section rate to 15% for low-risk first-time mothers, but that goal was not met and the rate of c-sections has been on the rise since 1996, and reached an all-time high in 2009 at 32.9%. Excessive and non-medically necessary cesareans can lead to complications that contribute to maternal mortality.[3]

Prevention

Inconsistent obstetric practice,[37] increase in women with chronic conditions, and lack of maternal health data all contribute to maternal mortality in the United States. According to a 2015 WHO editorial, a nationally implemented guideline for pregnancy and childbirth, along with easy and equal access to prenatal services and care, and active participation from all 50 states to produce better maternal health data are all necessary components to reduce maternal mortality.[38] The Hospital Corporation of America has also found that a uniform guideline for birth can improve maternal care overall. This would ultimately reduce the amount of maternal injury, c-sections, and mortality. The UK has had success drastically reducing preeclampsia deaths by implementing a nationwide standard protocol.[37] However, no such mandated guideline currently exists in the United States.[3]

To prevent maternal mortality moving forward, Amnesty International suggests these steps:

- Increase government accountability and coordination

- Create a national registry for maternal and infant health data, while incorporating intersections of gender, race, and social/economic factors

- Improve maternity care workforce

- Improve diversity in maternity care

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, out-of-hospital births (such as home births and birthing centers with midwifery assistance) "generally provided a lower risk profile than hospital births."[39]

Procedures such as Episiotomies and cesareans, while helpful in some cases, when administered unnecessarily increase the risk of maternal death.[3] Midwifery and mainstream obstetric care can be complementary,[14] which is commonly the case in Canada, where women have a wide arrange of pregnancy and birthing options, wherein informed choice and consent are fundamental tenants of their reformed maternity care.[40] The maternal mortality rate is two times lower in Canada than the United States, according to a global survey conducted by the United Nations and the World Bank.[41]

Gender bias, implicit bias, and obstetric violence in the medical field are also important factors when discussing maternal wellness, care, and death in the United States.[42]

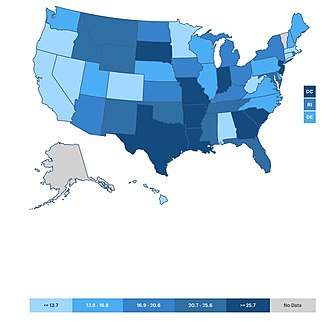

Comparisons by state

In the U.S., hospital bills for maternal healthcare costs over $98 billion, and concerns about the degradation of the maternal resulted in a state-by-state breakdown.

| State | Status | MMR* |

|---|---|---|

| California | 1 | 4.5 |

| Massachusetts | 2 | 6.1 |

| Nevada | 3 | 6.2 |

| Colorado | 4 | 11.3 |

| Hawaii | 5 | 11.7 |

| West Virginia | 5 | 11.7 |

| Alabama | 7 | 11.9 |

| Minnesota | 8 | 13.0 |

| Connecticut | 9 | 13.2 |

| Oregon | 10 | 13.7 |

| Delaware | 11 | 14.0 |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 14.3 |

| Washington | 13 | 14.8 |

| Virginia | 14 | 15.6 |

| Maine | 15 | 15.7 |

| North Carolina | 16 | 15.8 |

| Pennsylvania | 17 | 16.3 |

| Illinois | 18 | 16.6 |

| Nebraska | 19 | 16.8 |

| New Hampshire | 19 | 16.8 |

| Utah | 19 | 16.8 |

| Kansas | 22 | 17.7 |

| Iowa | 23 | 17.9 |

| Rhode Island | 24 | 18.3 |

| Arizona | 25 | 18.8 |

| North Dakota | 26 | 18.9 |

| Kentucky | 27 | 19.4 |

| Michigan | 27 | 19.4 |

| Ohio | 29 | 20.3 |

| New York | 30 | 20.6 |

| Idaho | 31 | 21.2 |

| Mississippi | 32 | 22.6 |

| Tennessee | 33 | 23.3 |

| Oklahoma | 34 | 23.4 |

| Maryland | 35 | 23.5 |

| Florida | 36 | 23.8 |

| Montana | 37 | 24.4 |

| Wyoming | 38 | 24.6 |

| New Mexico | 39 | 25.6 |

| South Carolina | 40 | 26.5 |

| South Dakota | 41 | 28.0 |

| Missouri | 42 | 32.6 |

| Texas | 43 | 34.2 |

| Arkansas | 44 | 34.8 |

| New Jersey | 45 | 38.1 |

| Indiana | 46 | 41.4 |

| Louisiana | 47 | 44.8 |

| Georgia | 48 | 46.2 |

No data on Alaska and Vermont.

*MMR: maternal mortality ratio- number of deaths per 100,000 births.[2]

Comparisons with other countries

Comparison of the US maternal death rate to the death rate in that of other countries is complicated by the lack of standardization. Some countries do not have a standard method for reporting maternal deaths and some count in statistics death only as a direct result of pregnancy.[43]

In the 1950s, the maternal mortality rate in the United Kingdom and the United States was the same—1 in 1000 pregnant and new mothers died. By 2018, the rate in the UK was three times lower than in the United States,[44] due to implementing a standardized protocol.[37] In 2010, Amnesty International published a 154-page report on maternal mortality in the United States.[45] In 2011, the United Nations described maternal mortality as a human rights issue at the forefront of American healthcare, as the mortality rates worsened over the years.[46] According to a 2015 WHO report, in the United States the MMR between 1990 and 2013 "more than doubled from an estimated 12 to 28 maternal deaths per 100,000 births."[47] By 2015, the United States had a higher MMR than the "Islamic Republic of Iran, Libya and Turkey".[38][48] In the 2017 NPR and ProPublica series "Lost Mothers: Maternal Mortality in the U.S." based on a six-month long collaborative investigation, they reported that the United States has the highest rate of maternal mortality than any other developed country, and it is the only country where mortality rate has been rising.[49] The maternal mortality rate in the United States is three times higher than that in neighboring Canada[37] and six times higher than in Scandinavia.[50]

Maternal Mortality Is Rising in the U.S. As It Declines Elsewhere[51]

Deaths per 100,000 live births

| Country | MMR (deaths per 100,000 live births) |

| United States | 26.4 |

| U.K | 9.2 |

| Portugal | 9 |

| Germany | 9 |

| France | 7.8 |

| Canada | 7.3 |

| Netherlands | 6.7 |

| Spain | 5.6 |

| Australia | 5.5 |

| Ireland | 4.7 |

| Sweden | 4.4 |

| Italy | 4.2 |

| Denmark | 4.2 |

| Finland | 3.8 |

There are many possible reasons to why the United States has a much larger MMR than other developed countries: many hospitals are unprepared for maternal emergencies, 44% maternal-fetal grants do not go towards the health of the mother, and pregnancy complication rates are continually increasing.

See also

- Maternal death

- Infant mortality

- Perinatal mortality

- Obstetric transition

- The Business of Being Born, a 2008 documentary

- Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in the UK

- List of women who died in childbirth

- Reproductive rights

- Women's reproductive health in the United States

References

- "Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System | Maternal and Infant Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-08-07. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- America's Health Rankings. "Maternal Mortality in the United States in 2018". United Health Foundation. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Deadly delivery : the maternal health care crisis in the USA. Amnesty International. London, England: Amnesty International Publications. 2010. ISBN 9780862104580. OCLC 694184792.CS1 maint: others (link)

- MacDorman, Marian F.; Declercq, Eugene; Cabral, Howard; Morton, Christine (2016). "Is the United States Maternal Mortality Rate Increasing? Disentangling trends from measurement issues Short title: U.S. Maternal Mortality Trends". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 128 (3): 447–455. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001556. ISSN 0029-7844. PMC 5001799. PMID 27500333.

- Troiano, Nan H.; Witcher, Patricia M. (2018). "Maternal Mortality and Morbidity in the United States". The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 32 (3): 222–231. doi:10.1097/jpn.0000000000000349. ISSN 0893-2190. PMID 30036304.

- "Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths". CDC Foundation. n.d. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "Report from Maternal Mortality Review Committees: A View Into Their Critical Role" (PDF). CDC Foundation. Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. January 1, 2017. p. 51. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Reports from Maternal Mortality Review Committees (Report). Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. CDC. 2018. p. 76.

- Martin, Nina (June 28, 2018). "U.S. Senate Committee Proposes $50 Million to Prevent Mothers Dying in Childbirth". Lost Mothers: Maternal Mortality in the U.S. ProPublica. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "Healthy Start". Mchb.hrsa.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- Chescheir, Nancy C. (September 2016). "Drilling Down on Maternal Mortality". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 128 (3): 427–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001600. PMID 27500323.

- Martin, Nina; Cillekens, Emma; Freitas, Alessandra (July 17, 2017). "Lost Mothers". ProPublica. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) | Healthy People 2020". www.healthypeople.gov. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- Morton, Christine H. "Where Are the Ethnographies of US Hospital Birth?" Anthropology News 50.3 (2009): 10-11. Web.

- Fields, Robin (November 15, 2017). "New York City Launches Committee to Review Maternal Deaths". ProPublica. Lost Mothers. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

Nationally, such data is so unreliable and incomplete that the United States has not published official annual counts of fatalities or an official maternal mortality rate in a decade.

- "De Blasio Administration Launches Comprehensive Plan to Reduce Maternal Deaths and Life-Threatening Complications from Childbirth Among Women of Color". NYC. July 20, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

Severe maternal morbidity is defined as life-threatening complications of childbirth; maternal mortality is defined as a death of a woman while pregnant or within one year of the termination of pregnancy due to any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.

- Kilpatrick, Sarah J (2015-03-01). "Next Steps to Reduce Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the USA". Women's Health. 11 (2): 193–199. doi:10.2217/whe.14.80. PMID 25776293.

- https://www.healthstream.com/resources/blog/blog/2018/09/24/suicide-and-overdose-equal-medical-conditions-as-reasons-for-maternal-mortality

- Williams manual of pregnancy complications. Leveno, Kenneth J., Alexander, James M., 1965- (23rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2013. ISBN 9780071765626. OCLC 793223461.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "UNESCO". UNESCO. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Ayala Quintanilla, Beatriz Paulina; Taft, Angela; McDonald, Susan; Pollock, Wendy; Roque Henriquez, Joel Christian (2016-11-28). "Social determinants and maternal exposure to intimate partner violence of obstetric patients with severe maternal morbidity in the intensive care unit: a systematic review protocol". BMJ Open. 6 (11): e013270. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013270. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 5168548. PMID 27895065.

- Murray Horwitz, Mara E.; Molina, Rose L.; Snowden, Jonathan M. (2018-11-01). "Postpartum Care in the United States — New Policies for a New Paradigm". New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (18): 1691–1693. doi:10.1056/nejmp1806516. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 30380385.

- Murray Horwitz, Mara E.; Molina, Rose L.; Snowden, Jonathan M. (2018-11-01). "Postpartum Care in the United States — New Policies for a New Paradigm". New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (18): 1691–1693. doi:10.1056/nejmp1806516. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 30380385.

- "Maternal mortality". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Strauss N, Giessler K, Mcallister E. How Doula Care Can Advance the Goals of the Affordable Care Act: A Snapshot From New York City. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 2015;24(1):8-15. doi:10.1891/1058-1243.24.1.8.

- Strauss N, Giessler K, Mcallister E. How Doula Care Can Advance the Goals of the Affordable Care Act: A Snapshot From New York City. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 2015;24(1):8-15. doi:10.1891/1058-1243.24.1.8.

- Thomas M-P AG, Brazier E, Noyes P, Maybank A. Doula Services Within a Healthy Start Program: Increasing Access for an Underserved Population. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2017;21(Suppl 1):59-64.

- Thomas M-P AG, Brazier E, Noyes P, Maybank A. Doula Services Within a Healthy Start Program: Increasing Access for an Underserved Population. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2017;21(Suppl 1):59-64.

- http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/LTM-III_Pregnancy-and-Birth.pdf

- Nelson, Daniel B.; Moniz, Michelle H.; Davis, Matthew M. (2018-08-13). "Population-level factors associated with maternal mortality in the United States, 1997–2012". BMC Public Health. 18 (1): 1007. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5935-2. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 6090644. PMID 30103716.

- Nelson, Daniel B.; Moniz, Michelle H.; Davis, Matthew M. (2018-08-13). "Population-level factors associated with maternal mortality in the United States, 1997–2012". BMC Public Health. 18 (1): 1007. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5935-2. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 6090644. PMID 30103716.

- "UNESCO". UNESCO. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Maternal mortality". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Maternal Health – Amnesty International USA". Amnesty International USA. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- Callaghan, W. M.; Seed, K.; Syverson, C.; Creanga, A. A. (August 2017). "Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011-2013". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 130 (2): 366–373. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002114. ISSN 0029-7844. PMC 5744583. PMID 28697109.

- Deadly delivery : the maternal health care crisis in the USA. Amnesty International. London, England: Amnesty International Publications. 2010. ISBN 9780862104580. OCLC 694184792.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Martin, Nina; Montagne, Renee (May 12, 2017). "Focus On Infants During Childbirth Leaves U.S. Moms In Danger". Lost Mothers: Maternal Mortality in the U.S. ProPublica NPR. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Agrawal, Priya (March 2015). "Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States of America". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 93 (3): 133–208. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.148627. PMC 4371496. PMID 25838608. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- MacDorman, Marian F., T. J. Mathews, Eugene R. Declercq, and National Center for Health Statistics , Issuing Body. Trends in Out-of-hospital Births in the United States, 1990-2012. NCHS Data Brief (Series) ; No. 144. 2014.

- MacDonald, Margaret. Chapter 4, At Work in the Field of Birth. 2007. Vanderbilt University Press.

- "U.S. maternal mortality rate is twice that of Canada: U.N". Reuters. 2015-11-12. Retrieved 2017-08-02.

- Diaz-Tello, Farah (2016). "Invisible wounds: Obstetric violence in the United States". Reproductive Health Matters. 24 (47): 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2016.04.004. PMID 27578339.

- "Medscape". www.medscape.com.

- Womersley, Kate (August 31, 2017). "Why Giving Birth Is Safer in Britain Than in the U.S." ProPublica. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "Deadly Delivery: The Maternal Healthcare Crisis in the USA". Amnesty International. London, UK. 2010-03-10. p. 154. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "Deadly Delivery: The Maternal Healthcare Crisis in the USA One Year Update 2011" (PDF). Amnesty International. New York. May 7, 2011. (pdf file: link). Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division (PDF). World Health Organization (Report). Geneva. 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Maternal mortality in 1990-2015 (PDF). World Health Organization (Report). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. Geneva: WHO. 2005. Retrieved August 4, 2018. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division

- Martin, Nina; Montagne, Renee (May 12, 2017). "U.S. Has The Worst Rate Of Maternal Deaths In The Developed World". Lost Mothers: Maternal Mortality in the U.S. ProPublica NPR. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Martin, Nina; Montagne, Renee (May 12, 2017). "The Last Person You'd Expect to Die in Childbirth". Lost Mothers: Maternal Mortality in the U.S. ProPublica. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "U.S. Has The Worst Rate Of Maternal Deaths In The Developed World". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-04-25.