Hypermetabolism

Hypermetabolism is the physiological state of increased rate of metabolic activity and is characterized by an abnormal increase in the body’s basal metabolic rate. Hypermetabolism is accompanied by a variety of internal and external symptoms, most notably extreme weight loss, and can also be a symptom in itself. This state of increased metabolic activity can signal underlying issues, especially hyperthyroidism. Patients with Fatal familial insomnia, an extremely rare and strictly hereditary disorder, also presents with hypermetabolism; however, this universally fatal disorder is exceedingly rare, with only a few known cases worldwide. The drastic impact of the hypermetabolic state on patient nutritional requirements is often understated or overlooked as well.

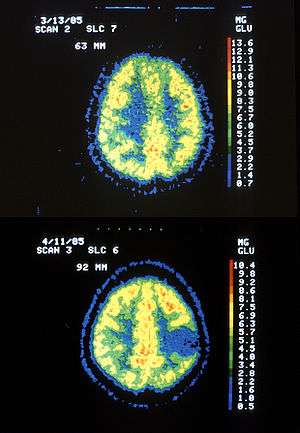

Hypermetabolism typically occurs after significant injury to the body. In hospitals and institutions, the most common causes are infections, sepsis, burns, multiple traumas, fever, long-bone fractures, hyperthyroidism, prolonged steroid therapy, surgery and bone marrow transplants. Hypermetabolism may occur in particular in the brain after traumatic brain injury. The cause and location of hypermetabolic symptoms within the body can be accurately detected by PET scan. Symptoms will usually subside once the underlying illness or injury is treated.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may last for days, weeks, or months until the injury is healed. The most apparent sign of hypermetabolism is an abnormally high intake of calories followed by continuous weight loss. Internal symptoms of hypermetabolism include but are not limited to: peripheral insulin resistance, elevated catabolism of protein, carbohydrates and triglycerides, and a negative nitrogen balance in the body.[1] Outward symptoms of hypermetabolism may include:

- Sudden weight loss

- Anemia

- Fatigue

- Elevated heart rate

- Irregular heartbeat

- Insomnia

- Dysautonomia

- Shortness of breath

- Muscle weakness

- Excessive sweating

Detection

Positron emission tomography (PET scan) is the primary means of detection for hyperthyroidism. This technique identifies both the location and the cause of hypermetabolic activity within the body. The resolution of PET scans, however, are limited and inconsistent in detecting the details of cortical alterations.[2]

Pathophysiology

During the acute phase, the liver redirects protein synthesis, causing up-regulation of certain proteins and down-regulation of others. Measuring the serum level of proteins that are up- and down-regulated during the acute phase can reveal extremely important information about the patient's nutritional state. The most important up-regulated protein is C-reactive protein, which can rapidly increase 20- to 1,000-fold during the acute phase. Hypermetabolism also causes expedited catabolism of carbohydrates, proteins, and triglycerides in order to meet the increased metabolic demands.

Differential diagnosis

Many different illnesses can cause an increase in metabolic activity as the body combats illness and disease in order to heal itself. Hypermetabolism is a common symptom of various pathologies. Some of the most prevalent diseases characterized by hypermetabolism are listed below.

- Hyperthyroidism: Manifestation: An overactive thyroid often causes a state of increased metabolic activity.[1]

- Friedreich's ataxia: Manifestation: Local cerebral metabolic activity is increased extensively as the disease progresses.[3]

- Fatal familial insomnia: Manifestation: Hypermetabolism in the thalamus occurs and disrupts sleep spindle formation that occurs there.[4]

- Graves' disease: Manifestation: Excess hypermetabolically-induced thyroid hormone activates sympathetic pathways, causing the eyelids to retract and remain constantly elevated.[5]

- Anorexia and bulimia: Manifestation: The prolonged stress put on the body as a result of these eating disorders forces the body into starvation mode. Some patients recovering from these disorders experience hypermetabolism until they resume normal diets.[6]

- Astrocytoma: Manifestation: Causes hypermetabolic lesions in the brain[7]

Treatment

Since hypermetabolism itself is a symptom and not an independent disease, treatment first and foremost requires attention to the underlying disease. Usually once the underlying cause is remedied, the symptoms will subside. The duration of symptoms depends upon the severity of the illness or trauma. Although hypermetabolism is a potentially dangerous condition that usually signals an underlying issue, it is one of the body’s strongest defenses against illness and injury.

References

- "What is Hypermetabolism?". Wise Geek. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Bar, M.D., Karl-Jurgen. "Serial Positron Emission Tomgraphic Findings in an Atypical Presentation of Fatal Familial Insomnia". Archives of Neurology. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Gilman; et al. "Cerebral Glucose Hypermetabolism in Friedreich's Ataxia Detected with Positron Emission Tomography" (PDF). Annals of Neurology. American Neurological Association. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Cortelli, Pietro. "Pre-symptomatic diagnosis in fatal familial insomnia: serial neurophysiological and FDG-PET studies" (PDF). Brain. Oxford Journal. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Trobe, M.D., Jonathan. "Graves' Disease: Proptosis, Lid Retraction, Strabismus, Optic Nerve Compression". The Eyes Have It. University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- "Re-Feeding". Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment of Eating Disorders. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Mirzaei; et al. (2001). "Diagnosis of Recurrent Astrocytoma with Fludeoxyglucose F18 PET Scanning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (26): 2030–2031. doi:10.1056/NEJM200106283442615. PMID 11430342.