Entamoeba polecki

Entamoeba polecki is an intestinal parasite[1] of the genus Entamoeba. E. polecki is found primarily in pigs and monkeys and is largely considered non-pathogenic in humans, although there have been some reports regarding symptomatic infections of humans. Prevalence is concentrated in New Guinea, with distribution also recorded in areas of southeast Asia, France, and the United States.[2]

| Entamoeba polecki | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | E. polecki |

| Binomial name | |

| Entamoeba polecki von Prowazek, 1912 | |

Morphology

Mature trophozoites of E. polecki are generally 10-20 μm in diameter. Trophozoites are irregularly shaped and possess pseudopodia for motility.[2] They have a single nucleus with a small central karyosome and finely dispersed peripheral chromatin, similar to that of Entamoeba histolytica[2]. Cytoplasmic contents are similar to other Entamoeba sp. and are usually granular and vacuolated.[2] Cysts of E. polecki are morphologically unique, containing only one nucleus, varyingly sized chromatoid bars, and a large inclusion mass.[2][3]

Transmission & Life Cycle

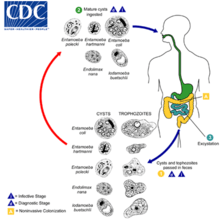

There are two stages in the life cycle of E. polecki.[4] The first is as a trophozoite, a vegetative stage that cannot survive in the environment.[4] The second is a cyst, where transmission of parasite is possible and provides protection to harsh external environments. Cysts are infective when ingested by another organism.[4] The cystic form of this protozoan has a diameter as small as 9.5 µm and as large as 17.5 µm. Morphologically, E. polecki is extremely similar to Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba hartmanni. [4]

Transmission follows a fecal-oral route. Infected feces with mature cysts are ingested where the cyst matures to the trophozoite in the gastrointestinal tract of the host. It is considered to be a zoonotic parasite, as close contact with infected swine have been reported to be the cause of E. polecki infections in humans.[5] Transmission to humans from consumption of pork is unlikely.[6] Recent studies suggest that different subspecies infect non-human primates and pigs, and close inhabitation between the two do not coincide with transmission.[7]

Pathology

E. polecki is considered to be non-pathogenic in humans. Nonspecific symptoms from infection have been reported, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloody stools, and fever.[8][5] Prevalence of infection amongst swine may be up to 25% across the world, but tend to be asymptomatic.[5]

Diagnosis and Treatment

Examination of stool samples for uninucleated cysts and trophozoites have been used for diagnosis.[8] This method is not always reliable due to morphological similarities between E. polecki and other Entamoeba species.[8][5] More recent diagnostic methods utilizing DNA amplification and comparison have been used to better differentiate amongst pathogenic and species such as E. histolytica and non-pathogenic species.[5] A definitive diagnosis can be made by using electroimmunotransfer blots.[4] Serological testing is not accurate between species of Entamoeba.[4]

Treatment of infection is similar to that of other Entamoeba infections. Anti-parasitic medications such as metronidazole and ornidazole are generally used to treat human infections.[2] Combination therapies such as metronidazole and diloxanide furoate have been effective as well.[5]

References

- Iran J Parasitol: Vol. 10, No. 2, Apr -Jun 2015, pp.146-156

- A., Gockel-Blessing, Elizabeth (2013). Clinical parasitology : a practical approach (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 9781416060444. OCLC 816557145.

- 1935-, Roberts, Larry S. (2005). Gerald D. Schmidt & Larry S. Roberts' foundations of parasitology. Janovy, John, Jr., 1937- (7th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0072348989. OCLC 54400427.

- "Entamoeba Polecki". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- Solaymani-Mohammadi, S.; Petri, W.A. (2006). "Zoonotic implications of the swine-transmitted protozoal infections". Veterinary Parasitology. 140 (3–4): 189–203. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.05.012. PMID 16828229.

- Djurković-Djaković, O.; Bobić, B.; Nikolić, A.; Klun, I.; Dupouy-Camet, J. (2013). "Pork as a source of human parasitic infection". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 19 (7): 586–594. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12162. PMID 23402388.

- Tuda, Josef; Feng, Meng; Imada, Mihoko; Kobayashi, Seiki; Cheng, Xunjia; Tachibana, Hiroshi (2016-09-01). "Identification ofEntamoeba poleckiwith Unique 18S rRNA Gene Sequences from Celebes Crested Macaques and Pigs in Tangkoko Nature Reserve, North Sulawesi, Indonesia". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 63 (5): 572–577. doi:10.1111/jeu.12304. ISSN 1550-7408. PMID 26861809.

- J., Magill, Alan (2012). Hunter's tropical medicine and emerging infectious disease. Strickland, G. Thomas., Maguire, James H., Ryan, Edward T., Solomon, Tom. (9th ed.). London: Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781416043904. OCLC 861539914.

- Cook R. Entamoeba Polecki [Internet]. Web.stanford.edu. 2004 [cited 23 March 2018]. Available from: https://web.stanford.edu/group/parasites/ParaSites2004/Entamoeba/Entamoeba%20Polecki.htm