Cori cycle

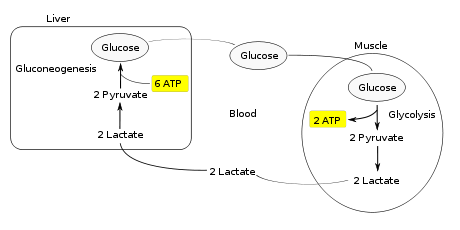

The Cori cycle (also known as the Lactic acid cycle), named after its discoverers, Carl Ferdinand Cori and Gerty Cori,[1] refers to the metabolic pathway in which lactate produced by anaerobic glycolysis in the muscles moves to the liver and is converted to glucose, which then returns to the muscles and is cyclically metabolized back to lactate.[2]

Cycle

_and_Carl_Ferdinand_Cori.jpg)

Muscular activity requires ATP, which is provided by the breakdown of glycogen in the skeletal muscles. The breakdown of glycogen, a process known as glycogenolysis, releases glucose in the form of glucose-1-phosphate (G-1-P). The G-1-P is converted to G-6-P by the enzyme phosphoglucomutase. G-6-P is readily fed into glycolysis, (or can go into the pentose phosphate pathway if G-6-P concentration is high) a process that provides ATP to the muscle cells as an energy source. During muscular activity, the store of ATP needs to be constantly replenished. When the supply of oxygen is sufficient, this energy comes from feeding pyruvate, one product of glycolysis, into the Krebs cycle.

When oxygen supply is insufficient, typically during intense muscular activity, energy must be released through anaerobic metabolism. Lactic acid fermentation converts pyruvate to lactate by lactate dehydrogenase. Most importantly, fermentation regenerates NAD+, maintaining the NAD+ concentration so that additional glycolysis reactions can occur. The fermentation step oxidizes the NADH produced by glycolysis back to NAD+, transferring two electrons from NADH to reduce pyruvate into lactate. (Refer to the main articles on glycolysis and fermentation for the details.)

Instead of accumulating inside the muscle cells, lactate produced by anaerobic fermentation is taken up by the liver. This initiates the other half of the Cori cycle. In the liver, gluconeogenesis occurs. From an intuitive perspective, gluconeogenesis reverses both glycolysis and fermentation by converting lactate first into pyruvate, and finally back to glucose. The glucose is then supplied to the muscles through the bloodstream; it is ready to be fed into further glycolysis reactions. If muscle activity has stopped, the glucose is used to replenish the supplies of glycogen through glycogenesis.[3]

Overall, the glycolysis part of the cycle produces 2 ATP molecules at a cost of 6 ATP molecules consumed in the gluconeogenesis part. Each iteration of the cycle must be maintained by a net consumption of 4 ATP molecules. As a result, the cycle cannot be sustained indefinitely. The intensive consumption of ATP molecules indicates that the Cori cycle shifts the metabolic burden from the muscles to the liver.

Significance

The cycle's importance is based on the prevention of lactic acidosis in the muscle under anaerobic conditions. However, normally before this happens the lactic acid is moved out of the muscles and into the liver.[3]

The cycle is also important in producing ATP, an energy source, during muscle activity. The Cori cycle functions more efficiently when muscle activity has ceased. This allows the oxygen debt to be repaid such that the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain can produce energy at peak efficiency.[3]

The Cori cycle is a much more important source of substrate for gluconeogenesis than food.[4][5] The contribution of Cori cycle lactate to overall glucose production increases with fasting duration before plateauing.[6] Specifically, after 12, 20, and 40 hours of fasting by human volunteers, gluconeogenesis accounts for 41%, 71%, and 92% of glucose production, but the contribution of Cori cycle lactate to gluconeogenesis is 18%, 35%, and 36%, respectively.[6] The remaining glucose production comes from protein breakdown,[6] muscle glycogen,[6] and glycerol from lipolysis.[7]

The drug metformin can cause lactic acidosis in patients with renal failure because metformin inhibits the hepatic gluconeogenesis of the Cori cycle, particularly the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex 1.[8] The buildup of lactate and its substrates for lactate production, pyruvate and alanine, lead to excess lactate.[9] Normally, the excess lactate would be cleared by the kidneys, but in patients with renal failure, the kidneys cannot handle the excess lactic acid.

See also

- Alanine cycle

- Citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle)

References

- acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/carbohydratemetabolism.html

- Nelson, David L., & Cox, Michael M.(2005) Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry Fourth Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, p. 543.

- "Cori Cycle Archived 2008-04-23 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved May 3, 2008, from Elmhurst, pp. 1–3.

- Gerich JE, Meyer C, Woerle HJ, Stumvoll M (2001). "Renal gluconeogenesis: Its importance in human glucose homeostasis" (PDF). Diabetes Care. 24 (2): 382–391. doi:10.2337/diacare.24.2.382. PMID 11213896.

- Nuttall FQ, Ngo A, Gannon MC (2008). "Regulation of hepatic glucose production and the role of gluconeogenesis in humans: is the rate of gluconeogenesis constant?" (PDF). Diabetes/metabolism Research and Reviews. 24 (6): 438–458. doi:10.1002/dmrr.863. PMID 18561209.

- Katz J, Tayek JA (1998). "Gluconeogenesis and the Cori cycle in 12-, 20-, and 40-h-fasted humans". American Journal of Physiology. 275 (3 Pt 1): E537–E542. PMID 9725823.

- Cahill GF (2006). "Fuel metabolism in starvation" (PDF). Annual Review of Nutrition. 26: 1–22. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111258. PMID 16848698.

- Vecchio, S. et al. "Metformin accumulation: lactic acidosis and high plasmatic metformin levels in a retrospective case series of 66 patients on chronic therapy.", Clin Toxicol. 2014;52(2).

- Sirtori CR, Pasik C. "Re-evaluation of a biguanide, metformin: mechanism of action and tolerability". Pharmacol Res 1994; 30.

Sources

- Smith, A.D., Datta, S.P., Smith, G. Howard, Campbell, P.N., Bentley, R., (Eds.) et al.(1997) Oxford Dictionary of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. New York: Oxford University Press.