Child abuse

Child abuse or child maltreatment is physical, sexual, and/or psychological maltreatment or neglect of a child or children, especially by a parent or a caregiver. Child abuse may include any act or failure to act by a parent or a caregiver that results in actual or potential harm to a child, and can occur in a child's home, or in the organizations, schools or communities the child interacts with.

| Criminal law | |

|---|---|

| Elements | |

|

|

| Scope of criminal liability | |

|

|

| Severity of offense | |

|

|

| Inchoate offenses | |

|

|

| Offence against the person | |

|

|

| Sexual offences | |

|

|

| Crimes against property | |

|

|

| Crimes against justice | |

|

|

| Crimes against the public | |

|

|

| Crimes against animals | |

|

|

| Crimes against the state | |

|

|

| Defences to liability | |

|

|

| Other common-law areas | |

|

|

| Portals | |

|

|

The terms child abuse and child maltreatment are often used interchangeably, although some researchers make a distinction between them, treating child maltreatment as an umbrella term to cover neglect, exploitation, and trafficking.

Different jurisdictions have developed their own definitions of what constitutes child abuse for the purposes of removing children from their families or prosecuting a criminal charge.

History

The whole of recorded history contains references to acts that can be described as child abuse or child maltreatment, but professional inquiry into the topic is generally considered to have begun in the 1960s.[1] The July 1962 publication of the paper "The Battered Child-Syndrome" authored principally to pediatric psychiatrist C. Henry Kempe and published in The Journal of the American Medical Association represents the moment that child maltreatment entered mainstream awareness. Before the article's publication, injuries to children—even repeated bone fractures—were not commonly recognized as the results of intentional trauma. Instead, physicians often looked for undiagnosed bone diseases or accepted parents' accounts of accidental mishaps such as falls or assaults by neighborhood bullies.[2]:100–103

The study of child abuse and neglect emerged as an academic discipline in the early 1970s in the United States. Elisabeth Young-Bruehl maintains that despite the growing numbers of child advocates and interest in protecting children which took place, the grouping of children into "the abused" and the "non-abused" created an artificial distinction that narrowed the concept of children's rights to simply protection from maltreatment, and blocked investigation of the ways in which children are discriminated against in society generally. Another effect of the way child abuse and neglect have been studied, according to Young-Bruehl, was to close off consideration of how children themselves perceive maltreatment and the importance they place on adults' attitudes toward them. Young-Bruehl writes that when the belief in children's inherent inferiority to adults is present in society, all children suffer whether or not their treatment is labeled as "abuse".[2]:15–16

Definitions

Definitions of what constitutes child abuse vary among professionals, between social and cultural groups, and across time.[3][4] The terms abuse and maltreatment are often used interchangeably in the literature.[5]:11 Child maltreatment can also be an umbrella term covering all forms of child abuse and child neglect.[1] Defining child maltreatment depends on prevailing cultural values as they relate to children, child development, and parenting.[6] Definitions of child maltreatment can vary across the sectors of society which deal with the issue,[6] such as child protection agencies, legal and medical communities, public health officials, researchers, practitioners, and child advocates. Since members of these various fields tend to use their own definitions, communication across disciplines can be limited, hampering efforts to identify, assess, track, treat, and prevent child maltreatment.[5]:3[7]

In general, abuse refers to (usually deliberate) acts of commission while neglect refers to acts of omission.[1][8] Child maltreatment includes both acts of commission and acts of omission on the part of parents or caregivers that cause actual or threatened harm to a child.[1] Some health professionals and authors consider neglect as part of the definition of abuse, while others do not; this is because the harm may have been unintentional, or because the caregivers did not understand the severity of the problem, which may have been the result of cultural beliefs about how to raise a child.[9][10] Delayed effects of child abuse and neglect, especially emotional neglect, and the diversity of acts that qualify as child abuse, are also factors.[10]

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines child abuse and child maltreatment as "all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child's health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power."[11] In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses the term child maltreatment to refer to both acts of commission (abuse), which include "words or overt actions that cause harm, potential harm, or threat of harm to a child", and acts of omission (neglect), meaning "the failure to provide for a child's basic physical, emotional, or educational needs or to protect a child from harm or potential harm".[5]:11 The United States federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act defines child abuse and neglect as, at minimum, "any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation" or "an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm".[12][13]

Types

The World Health Organization distinguishes four types of child maltreatment: physical abuse; sexual abuse; emotional (or psychological) abuse; and neglect.[14]

Physical abuse

Among professionals and the general public, there is disagreement as to what behaviors constitute physical abuse of a child.[15] Physical abuse often does not occur in isolation, but as part of a constellation of behaviors including authoritarian control, anxiety-provoking behavior, and a lack of parental warmth.[16] The WHO defines physical abuse as:

Intentional use of physical force against the child that results in – or has a high likelihood of resulting in – harm for the child's health, survival, development or dignity. This includes hitting, beating, kicking, shaking, biting, strangling, scalding, burning, poisoning and suffocating. Much physical violence against children in the home is inflicted with the object of punishing.[14]

Joan Durrant and Ron Ensom write that most physical abuse is physical punishment "in intent, form, and effect".[17] Overlapping definitions of physical abuse and physical punishment of children highlight a subtle or non-existent distinction between abuse and punishment.[18] For instance, Paulo Sergio Pinheiro writes in the UN Secretary-General's Study on Violence Against Children:

Corporal punishment involves hitting ('smacking', 'slapping', 'spanking') children, with the hand or with an implement – whip, stick, belt, shoe, wooden spoon, etc. But it can also involve, for example, kicking, shaking or throwing children, scratching, pinching, biting, pulling hair or boxing ears, forcing children to stay in uncomfortable positions, burning, scalding or forced ingestion (for example, washing children's mouths out with soap or forcing them to swallow hot spices).[19]

Most nations with child abuse laws deem the deliberate infliction of serious injuries, or actions that place the child at obvious risk of serious injury or death, to be illegal. Bruises, scratches, burns, broken bones, lacerations — as well as repeated "mishaps," and rough treatment that could cause physical injuries — can be physical abuse.[20] Multiple injuries or fractures at different stages of healing can raise suspicion of abuse.

The psychologist Alice Miller, noted for her books on child abuse, took the view that humiliations, spankings and beatings, slaps in the face, etc. are all forms of abuse, because they injure the integrity and dignity of a child, even if their consequences are not visible right away.[21]

Often, physical abuse as a child can lead to physical and mental difficulties in the future, including re-victimization, personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, dissociative disorders, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, eating disorders, substance abuse, and aggression. Physical abuse in childhood has also been linked to homelessness in adulthood.[22]

Sexual abuse

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a form of child abuse in which an adult or older adolescent abuses a child for sexual stimulation.[23] Sexual abuse refers to the participation of a child in a sexual act aimed toward the physical gratification or the financial profit of the person committing the act.[20][24] Forms of CSA include asking or pressuring a child to engage in sexual activities (regardless of the outcome), indecent exposure of the genitals to a child, displaying pornography to a child, actual sexual contact with a child, physical contact with the child's genitals, viewing of the child's genitalia without physical contact, or using a child to produce child pornography.[23][25][26] Selling the sexual services of children may be viewed and treated as child abuse rather than simple incarceration.[27]

Effects of child sexual abuse on the victim(s) include guilt and self-blame, flashbacks, nightmares, insomnia, fear of things associated with the abuse (including objects, smells, places, doctor's visits, etc.), self-esteem difficulties, sexual dysfunction, chronic pain, addiction, self-injury, suicidal ideation, somatic complaints, depression,[28] post-traumatic stress disorder,[29] anxiety,[30] other mental illnesses including borderline personality disorder[31] and dissociative identity disorder,[31] propensity to re-victimization in adulthood,[32] bulimia nervosa,[33] and physical injury to the child, among other problems.[34] Children who are the victims are also at an increased risk of sexually transmitted infections due to their immature immune systems and a high potential for mucosal tears during forced sexual contact.[35] Sexual victimization at a young age has been correlated with several risk factors for contracting HIV including decreased knowledge of sexual topics, increased prevalence of HIV, engagement in risky sexual practices, condom avoidance, lower knowledge of safe sex practices, frequent changing of sexual partners, and more years of sexual activity.[35]

In the United States, approximately 15% to 25% of women and 5% to 15% of men were sexually abused when they were children.[36][37][38] Most sexual abuse offenders are acquainted with their victims; approximately 30% are relatives of the child, most often brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, uncles or cousins; around 60% are other acquaintances such as friends of the family, babysitters, or neighbours; strangers are the offenders in approximately 10% of child sexual abuse cases.[36] In over one-third of cases, the perpetrator is also a minor.[39]

In 1999 the BBC reported on the RAHI Foundation's survey of sexual abuse in India, in which 76% of respondents said they had been abused as children, 40% of those stating the perpetrator was a family member.[40]

United States federal prosecutors registered multiple charges against a South Korean man for reportedly running the world's "largest dark web child porn marketplace." Reportedly, the English translated website "Welcome to Video", which has now been taken consisted of more than 200,000 videos or 8TB of data showing sexual acts involving infants, children and toddlers and processed about 7,300 Bitcoin, i.e. $730,000 worth of transactions.[41]

Psychological abuse

There are multiple definitions of child psychological abuse:

- In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) added Child Psychological Abuse to the DSM-5, describing it as "nonaccidental verbal or symbolic acts by a child's parent or caregiver that result, or have reasonable potential to result, in significant psychological harm to the child."[42]

- In 1995, APSAC defined it as: spurning, terrorizing, isolating, exploiting, corrupting, denying emotional responsiveness, or neglect" or "A repeated pattern of caregiver behavior or extreme incident(s) that convey to children that they are worthless, flawed, unloved, unwanted, endangered, or only of value in meeting another's needs"[43]

- In the United States, states laws vary, but most have laws against "mental injury"[44]

- Some have defined it as the production of psychological and social defects in the growth of a child as a result of behavior such as loud yelling, coarse and rude attitude, inattention, harsh criticism, and denigration of the child's personality.[20] Other examples include name-calling, ridicule, degradation, destruction of personal belongings, torture or killing of a pet, excessive criticism, inappropriate or excessive demands, withholding communication, and routine labeling or humiliation.[45]

In 2014, the APA stated that:[46]

- "Childhood psychological abuse [is] as harmful as sexual or physical abuse."

- "Nearly 3 million U.S. children experience some form of [psychological] maltreatment annually."

- Psychological maltreatment is "the most challenging and prevalent form of child abuse and neglect."

- "Given the prevalence of childhood psychological abuse and the severity of harm to young victims, it should be at the forefront of mental health and social service training"

In 2015, additional research confirmed these 2014 statements of the APA.[47][48]

Victims of emotional abuse may react by distancing themselves from the abuser, internalizing the abusive words, or fighting back by insulting the abuser. Emotional abuse can result in abnormal or disrupted attachment development, a tendency for victims to blame themselves (self-blame) for the abuse, learned helplessness, and overly passive behavior.[45]

Neglect

Child neglect is the failure of a parent or other person with responsibility for the child, to provide needed food, clothing, shelter, medical care, or supervision to the degree that the child's health, safety or well-being may be threatened with harm. Neglect is also a lack of attention from the people surrounding a child, and the non-provision of the relevant and adequate necessities for the child's survival, which would be a lack of attention, love, and nurturing.[20]

Some observable signs of child neglect include: the child is frequently absent from school, begs or steals food or money, lacks needed medical and dental care, is consistently dirty, or lacks appropriate clothing for the weather.[49] The 2010 Child Maltreatment Report (NCANDS), a yearly United States federal government report based on data supplied by state Child Protective Services (CPS) Agencies in the U.S., found that neglect/neglectful behavior was the "most common form of child maltreatment ".[50]

Neglectful acts can be divided into six sub-categories:[8]

- Supervisory neglect: characterized by the absence of a parent or guardian which can lead to physical harm, sexual abuse, or criminal behavior;

- Physical neglect: characterized by the failure to provide the basic physical necessities, such as a safe and clean home;

- Medical neglect: characterized by the lack of providing medical care;

- Emotional neglect: characterized by a lack of nurturance, encouragement, and support;

- Educational neglect: characterized by the caregivers lack to provide an education and additional resources to actively participate in the school system; and

- Abandonment: when the parent or guardian leaves a child alone for a long period of time without a babysitter or caretaker.

Neglected children may experience delays in physical and psychosocial development, possibly resulting in psychopathology and impaired neuropsychological functions including executive function, attention, processing speed, language, memory and social skills.[51] Researchers investigating maltreated children have repeatedly found that neglected children in the foster and adoptive populations manifest different emotional and behavioral reactions to regain lost or secure relationships and are frequently reported to have disorganized attachments and a need to control their environment. Such children are not likely to view caregivers as being a source of safety, and instead typically show an increase in aggressive and hyperactive behaviors which may disrupt healthy or secure attachment with their adopted parents. These children seem to have learned to adapt to an abusive and inconsistent caregiver by becoming cautiously self-reliant, and are often described as glib, manipulative and disingenuous in their interactions with others as they move through childhood.[52] Children who are victims of neglect can have a more difficult time forming and maintaining relationships, such as romantic or friendship, later in life due to the lack of attachment they had in their earlier stages of life.

Effects

Child abuse can result in immediate adverse physical effects but it is also strongly associated with developmental problems[53] and with many chronic physical and psychological effects, including subsequent ill-health, including higher rates of chronic conditions, high-risk health behaviors and shortened lifespan.[54][55]

Maltreated children may grow up to be maltreating adults.[56][57][58] A 1991 source reported that studies indicate that 90 percent of maltreating adults were maltreated as children.[59] Almost 7 million American infants receive child care services, such as day care, and much of that care is poor.[53]

Emotional

Child abuse can cause a range of emotional effects. Children who are constantly ignored, shamed, terrorized or humiliated suffer at least as much, if not more, than if they are physically assaulted.[60] According to the Joyful Heart Foundation, brain development of the child is greatly influenced and responds to the experiences with families, caregivers, and the community.[61] Abused children can grow up experiencing insecurities, low self-esteem, and lack of development. Many abused children experience ongoing difficulties with trust, social withdrawal, trouble in school, and forming relationships.[60]

Babies and other young children can be affected differently by abuse than their older counterparts. Babies and pre-school children who are being emotionally abused or neglected may be overly affectionate towards strangers or people they haven't known for very long.[62] They can lack confidence or become anxious, appear to not have a close relationship with their parent, exhibit aggressive behavior or act nasty towards other children and animals.[62] Older children may use foul language or act in a markedly different way to other children at the same age, struggle to control strong emotions, seem isolated from their parents, lack social skills or have few, if any, friends.[62]

Children can also experience reactive attachment disorder (RAD). RAD is defined as markedly disturbed and developmentally inappropriate social relatedness, that usually begins before the age of 5 years.[63] RAD can present as a persistent failure to start or respond in a developmentally appropriate fashion to most social situations. The long-term impact of emotional abuse has not been studied widely, but recent studies have begun to document its long-term consequences. Emotional abuse has been linked to increased depression, anxiety, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships (Spertus, Wong, Halligan, & Seremetis, 2003).[63] Victims of child abuse and neglect are more likely to commit crimes as juveniles and adults.[64]

Domestic violence also takes its toll on children; although the child is not the one being abused, the child witnessing the domestic violence is greatly influential as well. Research studies conducted such as the "Longitudinal Study on the Effects of Child Abuse and Children's Exposure to Domestic Violence", show that 36.8% of children engage in felony assault compared to the 47.5% of abused/assaulted children. Research has shown that children exposed to domestic violence increases the chances of experienced behavioral and emotional problems (depression, irritability, anxiety, academic problems, and problems in language development).[65]

Overall, emotional effects caused by child abuse and even witnessing abuse can result in long-term and short-term effects that ultimately affect a child's upbringing and development.

Physical

The immediate physical effects of abuse or neglect can be relatively minor (bruises or cuts) or severe (broken bones, hemorrhage, or even death). In some cases the physical effects are temporary; however, the pain and suffering they cause a child should not be discounted. Rib fractures may be seen with physical abuse, and if present may increase suspicion of abuse, but are found in a small minority of children with maltreatment-related injuries.[66][67]

The long-term impact of child abuse and neglect on physical health and development can be:

- Shaken baby syndrome. Shaking a baby is a common form of child abuse that often results in permanent neurological damage (80% of cases) or death (30% of cases).[68] Damage results from intracranial hypertension (increased pressure in the skull) after bleeding in the brain, damage to the spinal cord and neck, and rib or bone fractures.[69]

- Impaired brain development. Child abuse and neglect have been shown, in some cases, to cause important regions of the brain to fail to form or grow properly, resulting in impaired development.[70][71] Structural brain changes as a result of child abuse or neglect include overall smaller brain volume, hippocampal atrophy, prefrontal cortex dysfunction, decreased corpus callosum density, and delays in the myelination of synapses.[72][73] These alterations in brain maturation have long-term consequences for cognitive, language, and academic abilities.[74] In addition, these neurological changes impact the amygdala and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis which are involved in stress response and may cause post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.[73]

- Poor physical health. In addition to possible immediate adverse physical effects, household dysfunction and childhood maltreatment are strongly associated with many chronic physical and psychological effects, including subsequent ill-health in childhood,[75] adolescence[76] and adulthood, with higher rates of chronic conditions, high-risk health behaviors and shortened lifespan.[54][55] Adults who experienced abuse or neglect during childhood are more likely to suffer from physical ailments such as allergies, arthritis, asthma, bronchitis, high blood pressure, and ulcers.[55][77][78][79] There may be a higher risk of developing cancer later in life,[80] as well as possible immune dysfunction.[81]

- Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with shortened telomeres and with reduced telomerase activity.[82] The increased rate of telomere length reduction correlates to a reduction in lifespan of 7 to 15 years.[81]

- Data from a recent study supports previous findings that specific neurobiochemical changes are linked to exposure to violence and abuse, several biological pathways can possibly lead to the development of illness, and certain physiological mechanisms can moderate how severe illnesses become in patients with past experience with violence or abuse.[83]

- Recent studies give evidence of a link between stress occurring early in life and epigenetic modifications that last into adulthood.[71][84]

Adverse Childhood Experiences Study

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study is a long-running investigation into the relationship between childhood adversity, including various forms of abuse and neglect, and health problems in later life. The initial phase of the study was conducted in San Diego, California from 1995 to 1997.[85] The World Health Organization summarizes the study as: "childhood maltreatment and household dysfunction contribute to the development – decades later – of the chronic diseases that are the most common causes of death and disability in the United States... A strong relationship was seen between the number of adverse experiences (including physical and sexual abuse in childhood) and self-reports of cigarette smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, attempted suicide, sexual promiscuity and sexually transmitted diseases in later life."[14]

A long-term study of adults retrospectively reporting adverse childhood experiences including verbal, physical and sexual abuse, as well as other forms of childhood trauma found 25.9% of adults reported verbal abuse as children, 14.8% reported physical abuse, and 12.2% reported sexual abuse. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System corroborate these high rates.[86] There is a high correlation between the number of different adverse childhood experiences (A.C.E.s) and risk for poor health outcomes in adults including cancer, heart attack, mental illness, reduced longevity drug and alcohol abuse.[87] An anonymous self-reporting survey of Washington State students finds 6–7% of 8th, 10th and 12th grade students actually attempt suicide. Rates of depression are twice as high. Other risk behaviors are even higher.[88] There is a relationship between child physical and sexual abuse and suicide.[89] For legal and cultural reasons as well as fears by children of being taken away from their parents most childhood abuse goes unreported and unsubstantiated.

It has been discovered that childhood abuse can lead to the addiction of drugs and alcohol in adolescence and adult life. Studies show that any type of abuse experienced in childhood can cause neurological changes making an individual more prone to addictive tendencies. A significant study examined 900 court cases of children who had experienced sexual and physical abuse along with neglect. The study found that a large sum of the children who were abused are now currently addicted to alcohol. This case study outlines how addiction is a significant effect of childhood abuse.[90]

Psychological

Children who have a history of neglect or physical abuse are at risk of developing psychiatric problems,[91][92] or a disorganized attachment style.[93][94][95] In addition, children who experience child abuse or neglect are 59% more likely to be arrested as juveniles, 28% more likely to be arrested as adults, and 30% more likely to commit violent crime.[96] Disorganized attachment is associated with a number of developmental problems, including dissociative symptoms,[97] as well as anxiety, depressive, and acting out symptoms.[98][99] A study by Dante Cicchetti found that 80% of abused and maltreated infants exhibited symptoms of disorganized attachment.[100][101] When some of these children become parents, especially if they suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociative symptoms, and other sequelae of child abuse, they may encounter difficulty when faced with their infant and young children's needs and normative distress, which may in turn lead to adverse consequences for their child's social-emotional development.[102][103] Additionally, children may find it difficult to feel empathy towards themselves or others, which may cause them to feel alone and unable to make friends.[65] Despite these potential difficulties, psychosocial intervention can be effective, at least in some cases, in changing the ways maltreated parents think about their young children.[104]

Victims of childhood abuse also suffer from different types of physical health problems later in life. Some reportedly suffer from some type of chronic head, abdominal, pelvic, or muscular pain with no identifiable reason.[105] Even though the majority of childhood abuse victims know or believe that their abuse is, or can be, the cause of different health problems in their adult life, for the great majority their abuse was not directly associated with those problems, indicating that sufferers were most likely diagnosed with other possible causes for their health problems, instead of their childhood abuse.[105] One long-term study found that up to 80% of abused people had at least one psychiatric disorder at age 21, with problems including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and suicide attempts.[106] One Canadian hospital found that between 36% and 76% of women mental health outpatients had been sexually abused, as had 58% of women and 23% of men schizophrenic inpatients.[107] A recent study has discovered that a crucial structure in the brain's reward circuits is compromised by childhood abuse and neglect, and predicts Depressive Symptoms later in life.[108]

In the case of 23 of the 27 illnesses listed in the questionnaire of a French INSEE survey, some statistically significant correlations were found between repeated illness and family traumas encountered by the child before the age of 18 years. According to Georges Menahem, the French sociologist who found out these correlations by studying health inequalities, these relationships show that inequalities in illness and suffering are not only social. Health inequality also has its origins in the family, where it is associated with the degrees of lasting affective problems (lack of affection, parental discord, the prolonged absence of a parent, or a serious illness affecting either the mother or father) that individuals report having experienced in childhood.[109]

Many children who have been abused in any form develop some sort of psychological problem. These problems may include: anxiety, depression, eating disorders, OCD, co-dependency, or even a lack of human connections. There is also a slight tendency for children who have been abused to become child abusers themselves. In the U.S. in 2013, of the 294,000 reported child abuse cases only 81,124 received any sort of counseling or therapy. Treatment is greatly important for abused children.[110]

On the other hand, there are some children who are raised in child abuse, but who manage to do unexpectedly well later in life regarding the preconditions. Such children have been termed dandelion children, as inspired from the way that dandelions seem to prosper irrespective of soil, sun, drought, or rain.[111] Such children (or currently grown-ups) are of high interest in finding factors that mitigate the effects of child abuse.

Causes

Child abuse is a complex phenomenon with multiple causes.[112] No single factor can be identified as to why some adults behave abusively or neglectfully toward children. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN) identify multiple factors at the level of the individual, their relationships, their local community, and their society at large, that combine to influence the occurrence of child maltreatment. At the individual level, such factors include age, sex, and personal history, while at the level of society, factors contributing to child maltreatment include cultural norms encouraging harsh physical punishment of children, economic inequality, and the lack of social safety nets.[14] WHO and ISPCAN state that understanding the complex interplay of various risk factors is vital for dealing with the problem of child maltreatment.[14]

The American psychoanalyst Elisabeth Young-Bruehl maintains that harm to children is justified and made acceptable by widely held beliefs in children's inherent subservience to adults, resulting in a largely unacknowledged prejudice against children she terms childism. She contends that such prejudice, while not the immediate cause of child maltreatment, must be investigated in order to understand the motivations behind a given act of abuse, as well as to shed light on societal failures to support children's needs and development in general.[2]:4–6 Founding editor of the International Journal of Children's Rights, Michael Freeman, also argues that the ultimate causes of child abuse lie in prejudice against children, especially the view that human rights do not apply equally to adults and children. He writes, "the roots of child abuse lie not in parental psycho-pathology or in socio-environmental stress (though their influences cannot be discounted) but in a sick culture which denigrates and depersonalizes, which reduces children to property, to sexual objects so that they become the legitimate victims of both adult violence and lust".[113]

Parents who physically abuse their spouses are more likely than others to physically abuse their children.[114] However, it is impossible to know whether marital strife is a cause of child abuse, or if both the marital strife and the abuse are caused by tendencies in the abuser.[114] Sometimes, parents set expectations for their child that are clearly beyond the child's capability. When parents' expectations are far beyond what is appropriate to the child (e.g., preschool children who are expected to be totally responsible for self-care or provision of nurturance to parents) the resulting frustration caused by the child's non-compliance is believed to function as a contributory if not necessary cause of child abuse.[115]

Most acts of physical violence against children are undertaken with the intent to punish.[116] In the United States, interviews with parents reveal that as many as two thirds of documented instances of physical abuse begin as acts of corporal punishment meant to correct a child's behavior, while a large-scale Canadian study found that three quarters of substantiated cases of physical abuse of children have occurred within the context of physical punishment.[117] Other studies have shown that children and infants who are spanked by parents are several times more likely to be severely assaulted by their parents or suffer an injury requiring medical attention. Studies indicate that such abusive treatment often involves parents attributing conflict to their child's willfulness or rejection, as well as "coercive family dynamics and conditioned emotional responses".[17] Factors involved in the escalation of ordinary physical punishment by parents into confirmed child abuse may be the punishing parent's inability to control their anger or judge their own strength, and the parent being unaware of the child's physical vulnerabilities.[16]

Some professionals argue that cultural norms that sanction physical punishment are one of the causes of child abuse, and have undertaken campaigns to redefine such norms.[118][119][120]

Children resulting from unintended pregnancies are more likely to be abused or neglected.[121][122] In addition, unintended pregnancies are more likely than intended pregnancies to be associated with abusive relationships,[123] and there is an increased risk of physical violence during pregnancy.[124] They also result in poorer maternal mental health,[124] and lower mother-child relationship quality.[124]

There is some limited evidence that children with moderate or severe disabilities are more likely to be victims of abuse than non-disabled children.[125] A study on child abuse sought to determine: the forms of child abuse perpetrated on children with disabilities; the extent of child abuse; and the causes of child abuse of children with disabilities. A questionnaire on child abuse was adapted and used to collect data in this study. Participants comprised a sample of 31 pupils with disabilities (15 children with vision impairment and 16 children with hearing impairment) selected from special schools in Botswana. The study found that the majority of participants were involved in doing domestic chores. They were also sexually, physically and emotionally abused by their teachers. This study showed that children with disabilities were vulnerable to child abuse in their schools.[126]

Substance abuse can be a major contributing factor to child abuse. One U.S. study found that parents with documented substance abuse, most commonly alcohol, cocaine, and heroin, were much more likely to mistreat their children, and were also much more likely to reject court-ordered services and treatments.[127] Another study found that over two-thirds of cases of child maltreatment involved parents with substance abuse problems. This study specifically found relationships between alcohol and physical abuse, and between cocaine and sexual abuse.[128] Also parental stress caused by substance increases the likelihood of the minor exhibiting internalizing and externalizing behaviors.[129] Although the abuse victim does not always realize the abuse is wrong, the internal confusion can lead to chaos. Inner anger turns to outer frustration. Once aged 17/18, drink and drugs are used to numb the hurt feelings, nightmares and daytime flashbacks. Acquisitive crimes to pay for the chemicals are inevitable if the victim is unable to find employment.[130]

Unemployment and financial difficulties are associated with increased rates of child abuse.[131] In 2009 CBS News reported that child abuse in the United States had increased during the economic recession. It gave the example of a father who had never been the primary care-taker of the children. Now that the father was in that role, the children began to come in with injuries.[132]

Parental mental health has also been seen as a factor towards child maltreatment.[133] According to a recent Children’s HealthWatch study, mother's positive symptoms of depression display a greater rate of food insecurity, poor health care for their children, and greater number of hospitalizations.[134]

Worldwide

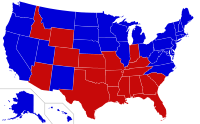

Corporal punishment of minors in the United States

Child abuse is an international phenomenon. Poverty and substance abuse are common social problems worldwide, and no matter the location, show a similar trend in the correlation to child abuse. Although these factors can likely contribute to child maltreatment, differences in cultural perspectives play a significant role in the treatment of children. Laws may influence the population's views on what is acceptable - for example whether child corporal punishment is legal or not.

A study conducted by members from several Baltic and Eastern European countries, together with specialists from the United States, examined the causes of child abuse in the countries of Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia and Moldova. In these countries, respectively, 33%, 42%, 18% and 43% of children reported at least one type of child abuse.[135] According to their findings, there was a series of correlations between the potential risk factors of parental employment status, alcohol abuse, and family size within the abuse ratings.[136] In three of the four countries, parental substance abuse was considerably correlated with the presence of child abuse, and although it was a lower percentage, still showed a relationship in the fourth country (Moldova).[136] Each country also showed a connection between the father not working outside of the home and either emotional or physical child abuse.[136] After the fall of the communism regime, some positive changes have followed with regard to tackling child abuse. While there is a new openness and acceptance regarding parenting styles and close relationships with children, child abuse still remains a serious concern. Although it is now more publicly recognized, it has certainly not ceased to exist. While controlling parenting may be less of a concern, financial difficulty, unemployment, and substance abuse still remain to be dominating factors in child abuse throughout Eastern Europe.[136]

These cultural differences can be studied from many perspectives. Most importantly, overall parental behavior is genuinely different in various countries. Each culture has their own "range of acceptability," and what one may view as offensive, others may seem as tolerable. Behaviors that are normal to some may be viewed as abusive to others, all depending on the societal norms of that particular country.[136]

Asian parenting perspectives, specifically, hold different ideals from American culture. Many have described their traditions as including physical and emotional closeness that ensures a lifelong bond between parent and child, as well as establishing parental authority and child obedience through harsh discipline.[137] Balancing disciplinary responsibilities within parenting is common in many Asian cultures, including China, Japan, Singapore, Vietnam and Korea.[137] To some cultures, forceful parenting may be seen as abuse, but in other societies such as these, the use of force is looked at as a reflection of parental devotion.[137]

The differences in these cultural beliefs demonstrate the importance of examining all cross-cultural perspectives when studying the concept of child abuse.

As of 2006, between 25,000 and 50,000 children in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, had been accused of witchcraft and abandoned.[138] In Malawi it is also common practice to accuse children of witchcraft and many children have been abandoned, abused and even killed as a result.[139] In the Nigeria, Akwa Ibom State and Cross River State about 15,000 children were branded as witches.[140]

In April 2015, public broadcasting showed that rate of child abuse in South Korea had increased to 13% compared with the previous year, and 75% of attackers were the children's own parents.[141]

Disclosure and diagnosis

Suspicion for physical abuse is recommended when an injury occurs in a child who does not yet move independently, injuries are in unusual areas, more than one injury at different stages of healing, symptoms of possible head trauma, and injuries to more than one body system.[142]

In many jurisdictions, abuse that is suspected, not necessarily proven, requires reporting to child protection agencies, such as the Child Protection Services in the United States. Recommendations for healthcare workers, such as primary care providers and nurses, who are often suited to encounter suspected abuse are advised to firstly determine the child’s immediate need for safety. A private environment away from suspected abusers is desired for interviewing and examining. Leading statements that can distort the story are avoided. As disclosing abuse can be distressing and sometimes even shameful, reassuring the child that he or she has done the right thing by telling and that they are not bad or that the abuse was not their fault helps in disclosing more information. Dolls are sometimes used to help explain what happened. For the suspected abusers, it is also recommended to use a nonjudgmental, nonthreatening attitude towards them and to withhold expressing shock, in order to help disclose information.[143]

Assessment

A key part of child abuse work is assessment.

A few methods of assessment include projective tests, clinical interviews, and behavioral observations.

- Projective tests allow for the child to express themselves through drawings, stories, or even descriptions in order to get help establish an initial understanding of the abuse that took place

- Clinical interviews are comprehensive interviews performed by professionals to analyze the mental state of the one being interviewed

- Behavioral observation gives an insight into things that trigger a child's memory of the abuse through observation of the child's behavior when interacting with other adults or children

A particular challenge arises where child protection professionals are assessing families where neglect is occurring. Professionals conducting assessments of families where neglect is taking place are said to sometimes make the following errors:[144]

- Failure to ask the right types of question, including

- Whether neglect is occurring;

- Why neglect is occurring;

- What the situation is like for the child;

- Whether improvements in the family are likely to be sustained;

- What needs to be done to ensure the long-term safety of the child?

Prevention

A support-group structure is needed to reinforce parenting skills and closely monitor the child's well-being. Visiting home nurse or social-worker visits are also required to observe and evaluate the progress of the child and the caretaking situation.

The support-group structure and visiting home nurse or social-worker visits are not mutually exclusive. Many studies have demonstrated that the two measures must be coupled together for the best possible outcome.[145]

Studies show that if health and medical care personnel in a structured way ask parents about important psychosocial risk factors in connection with visiting pediatric primary care and, if necessary, offering the parent help may help prevent child maltreatment.[146][147]

Children's school programs regarding "good touch … bad touch" can provide children with a forum in which to role-play and learn to avoid potentially harmful scenarios. Pediatricians can help identify children at risk of maltreatment and intervene with the aid of a social worker or provide access to treatment that addresses potential risk factors such as maternal depression.[148] Videoconferencing has also been used to diagnose child abuse in remote emergency departments and clinics.[149] Unintended conception increases the risk of subsequent child abuse, and large family size increases the risk of child neglect.[122] Thus, a comprehensive study for the National Academy of Sciences concluded that affordable contraceptive services should form the basis for child abuse prevention.[122][150] "The starting point for effective child abuse programming is pregnancy planning," according to an analysis for US Surgeon General C. Everett Koop.[122][151]

Child sexual abuse prevention programmes were developed in the United States of America during the 1970s and originally delivered to children. Programmes delivered to parents were developed in the 1980s and took the form of one-off meetings, two to three hours long.[152][153][154][155][156][157] In the last 15 years, web-based programmes have been developed.

April has been designated Child Abuse Prevention Month in the United States since 1983.[158] U.S. President Barack Obama continued that tradition by declaring April 2009 Child Abuse Prevention Month.[159] One way the Federal government of the United States provides funding for child-abuse prevention is through Community-Based Grants for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (CBCAP).[160]

Resources for child-protection services are sometimes limited. According to Hosin (2007), "a considerable number of traumatized abused children do not gain access to protective child-protection strategies."[161] Briere (1992) argues that only when "lower-level violence" of children ceases to be culturally tolerated will there be changes in the victimization and police protection of children.[162]

Findings from recent research support the importance of family relationships in the trajectory of a child’s life: family-targeted interventions are important for improving long-term health, particularly in communities that are socioeconomically disadvantaged.[163]

Treatment

A number of treatments are available to victims of child abuse.[164] However, children who experience childhood trauma do not heal from abuse easily.[165] There are focused cognitive behavioral therapy, first developed to treat sexually abused children, is now used for victims of any kind of trauma. It targets trauma-related symptoms in children including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), clinical depression and anxiety. It also includes a component for non-offending parents. Several studies have found that sexually abused children undergoing TF-CBT improved more than children undergoing certain other therapies. Data on the effects of TF-CBT for children who experienced only non-sexual abuse was not available as of 2006.[164] The purpose of dealing with the thoughts and feelings associated with the trauma is to deal with nightmares, flashbacks and other intrusive experiences that might be spontaneously brought on by any number of discriminative stimuli in the environment or in the individual’s brain. This would aid the individual in becoming less fearful of specific stimuli that would arouse debilitating fear, anger, sadness or other negative emotion. In other words, the individual would have some control or mastery over those emotions.[52]

Parenting training can prevent child abuse in the short term, and help children with a range of emotional, conduct and behavioural challenges, but there is insufficient evidence about whether it treat parents who already abuse their children.[166]

Abuse-focused cognitive behavioral therapy was designed for children who have experienced physical abuse. It targets externalizing behaviors and strengthens prosocial behaviors. Offending parents are included in the treatment, to improve parenting skills/practices. It is supported by one randomized study.[164]

Rational Cognitive Emotive Behavior Therapy consists of ten distinct but interdependent steps. These steps fall into one of three theoretical orientations (i.e., rational or solution focused, cognitive emotive, and behavioral) and are intended to provide abused children and their adoptive parents with positive behavior change, corrective interpersonal skills, and greater control over themselves and their relationships. They are: 1) determining and normalizing thinking and behaving, 2) evaluating language, 3) shifting attention away from problem talk 4) describing times when the attachment problem isn't happening, 5) focusing on how family members "successfully" solve problematic attachment behavior; 6) acknowledging "unpleasant emotions" (i.e., angry, sad, scared) underlying negative interactional patterns, 7) identifying antecedents (controlling conditions) and associated negative cognitive emotive connections in behavior (reciprocal role of thought and emotion in behavioral causation), 8) encouraging previously abused children to experience or "own" negative thoughts and associated aversive emotional feelings, 9) modeling and rewarding positive behavior change (with themselves and in relationships), and 10) encouraging and rewarding thinking and behaving differently. This type of therapy shifts victims thoughts away from the bad and changes their behavior.[52]

Parent–child interaction therapy was designed to improve the child-parent relationship following the experience of domestic violence. It targets trauma-related symptoms in infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, including PTSD, aggression, defiance, and anxiety. It is supported by two studies of one sample.[164]

Other forms of treatment include group therapy, play therapy, and art therapy. Each of these types of treatment can be used to better assist the client, depending on the form of abuse they have experienced. Play therapy and art therapy are ways to get children more comfortable with therapy by working on something that they enjoy (coloring, drawing, painting, etc.). The design of a child's artwork can be a symbolic representation of what they are feeling, relationships with friends or family, and more. Being able to discuss and analyze a child's artwork can allow a professional to get a better insight of the child.[167]

Prevalence

Child abuse is complex and difficult to study. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), estimates of the rates of child maltreatment vary widely by country, depending on how child maltreatment is defined, the type of maltreatment studied, the scope and quality of data gathered, and the scope and quality of surveys that ask for self-reports from victims, parents, and caregivers. Despite these limitations, international studies show that a quarter of all adults report experiencing physical abuse as children, and that 1 in 5 women and 1 in 13 men report experiencing childhood sexual abuse. Emotional abuse and neglect are also common childhood experiences.[168]

As of 2014, an estimated 41,000 children under 15 are victims of homicide each year. The WHO states that this number underestimates the true extent of child homicide; a significant proportion of child deaths caused by maltreatment are incorrectly attributed to unrelated factors such as falls, burns, and drowning. Also, girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence, exploitation and abuse in situations of armed conflict and refugee settings, whether by combatants, security forces, community members, aid workers, or others.[168]

United States

The National Research Council wrote in 1993 that "...the available evidence suggests that child abuse and neglect is an important, prevalent problem in the United States [...] Child abuse and neglect are particularly important compared with other critical childhood problems because they are often directly associated with adverse physical and mental health consequences in children and families".[169]:6

In 2012, Child Protective Services (CPS) agencies estimated that approximately 9 out of 1000 children in the United States were victims of child maltreatment. Most (78%) were victims of neglect. Physical abuse, sexual abuse, and other types of maltreatment, were less common, making up 18%, 9%, and 11% of cases, respectively ("other types" included emotional abuse, parental substance abuse, and inadequate supervision). According to data reported by the Children’s Bureau of the US Department of Health and Human Services, more than 3 million allegations of child abuse were looked into by child protective services who in turn confirmed 683,000 of those cases in 2015.[170] However, CPS reports may underestimate the true scope of child maltreatment. A non-CPS study estimated that one in four children experience some form of maltreatment in their lifetimes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[171]

In Feb 2017, American Public Health Association published a Washington University study estimating 37% of American children experiencing a child protective services investigation by age 18 (or 53% if African American).[172]

David Finkelhor tracked Child Maltreatment Report (NCANDS) data from 1990 to 2010. He states that sexual abuse had declined 62% from 1992 to 2009. The long-term trend for physical abuse was also down by 56% since 1992. The decline in sexual abuse adds to an already substantial positive long-term trend. He states: "It is unfortunate that information about the trends in child maltreatment are not better publicized and more widely known. The long-term decline in sexual and physical abuse may have important implications for public policy."[173]

Douglas J. Besharov, the first Director of the U.S. Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, states "the existing laws are often vague and overly broad"[174] and there is a "lack of consensus among professionals and Child Protective Services (CPS), personnel about what the terms abuse and neglect mean".[175] Susan Orr, former head of the United States Children's Bureau U.S. Department of Health and Services Administration for Children and Families, 2001–2007, states that "much that is now defined as child abuse and neglect does not merit governmental interference".[176]

A child abuse fatality occurs when a child's death is the result of abuse or neglect, or when abuse or neglect are contributing factors to a child's death. In the United States, 1,730 children died in 2008 due to factors related to abuse; this is a rate of 2 per 100,000 U.S. children.[177] Family situations which place children at risk include moving, unemployment, and having non-family members living in the household. A number of policies and programs have been put in place in the U.S. to try to better understand and to prevent child abuse fatalities, including: safe-haven laws, child fatality review teams, training for investigators, shaken baby syndrome prevention programs, and child abuse death laws which mandate harsher sentencing for taking the life of a child.[178]

A one off judicial decision found that parents failing to sufficiently speak the national standard language at home to their children was a form of child abuse by a judge in a child custody matter.[179]

Examples

Child labor

Child labor refers to the employment of children in any work that deprives children of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful.[180] The International Labour Organization considers such labor to be a form of exploitation and abuse of children.[181][182] Child labor refers to those occupations which infringe the development of children (due to the nature of the job or lack of appropriate regulation) and does not include age appropriate and properly supervised jobs in which minors may participate. According to ILO, globally, around 215 million children work, many full-time. Many of these children do not go to school, do not receive proper nutrition or care, and have little or no time to play. More than half of them are exposed to the worst forms of child labor, such as child prostitution, drug trafficking, armed conflicts and other hazardous environments.[183] There exist several international instruments protecting children from child labor, including the Minimum Age Convention, 1973 and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention.

More girls under 16 work as domestic workers than any other category of child labor, often sent to cities by parents living in rural poverty[184] such as in restaveks in Haiti.

Child trafficking

Child trafficking is the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of children for the purpose of exploitation.[185] Children are trafficked for purposes such as of commercial sexual exploitation, bonded labour, camel jockeying, child domestic labour, drug couriering, child soldiering, illegal adoptions, begging.[186][187][188] It is difficult to obtain reliable estimates concerning the number of children trafficked each year, primarily due to the covert and criminal nature of the practice.[189][190] The International Labour Organization estimates that 1.2 million children are trafficked each year.[191]

In Switzerland, between the 1850s and the mid-20th century, hundreds of thousands of children were forcefully removed from their parents by the authorities, and sent to work on farms, living with new families. These children usually came from poor or single parents, and were used as free labor by farmers, and were known as contract children or Verdingkinder.[192][193][194][195]

Other policies of organized child abduction and selling of children in the 20th century include the Lost children of Francoism (in Spain) and the disappearance of the children of Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (in Argentina).

Forced adoption

In some Western countries throughout the 20th century and until the 1970s, children from certain ethnic minority origins were forcefully removed from their families and communities by state and church authorities and forced to "assimilate". Such policies include the Stolen Generations (in Australia for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children) and the Canadian Indian residential school system (in Canada for First Nations, Métis and Inuit), with such children often suffering severe abuse.[196][197][198][199][200][201][202]

Gender based violence against girls

Infanticide

Under natural conditions, mortality rates for girls under five are slightly lower than boys for biological reasons. However, after birth, neglect and diverting resources to male children can lead to some countries having a skewed ratio with more boys than girls, with such practices killing an approximate 230,000 girls under five in India each year.[203] While sex-selective abortion is more common among the higher income population, who can access medical technology, abuse after birth, such as infanticide and abandonment, is more common among the lower income population. Female infanticide in Pakistan is a common practice.[204] Methods proposed to deal with the issue are baby hatches to drop off unwanted babies and safe-haven laws, which decriminalize abandoning babies unharmed.[205]

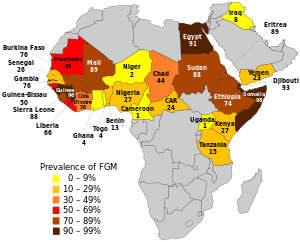

Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."[207] It is practiced mainly in 28 countries in Africa, and in parts of Asia and the Middle East.[208][209] FGM is mostly found in a geographical area ranging across Africa, from east to west – from Somalia to Senegal, and from north to south – from Egypt to Tanzania.[210] FGM is most often carried out on young girls aged between infancy and 15 years.[207] FGM is classified into four types, of which type 3 – infibulation – is the most extreme form.[207] The consequences of FGM include physical, emotional and sexual problems, and include serious risks during childbirth.[211][212] In Western countries this practice is illegal and considered a form of child abuse.[212][213] The countries which choose to ratify the Istanbul Convention, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women and domestic violence,[214] are bound by its provisions to ensure that FGM is criminalized.[215] In Australia, all states and territories have outlawed FGM.[216] In the United States, performing FGM on anyone under the age of 18 became illegal in 1996 with the Federal Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act.[217]

Sexual initiation of virgins

A tradition often performed in some regions in Africa involves a man initiating a girl into womanhood by having sex with her, usually after her first period, in a practice known as "sexual cleansing". The rite can last for three days and there is an increased risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections as the ritual requires condoms not be worn.[218]

Breast ironing

The practice of using hot stones or other implements to flatten the breast tissue of pubescent girls is widespread in Cameroon[219] and exists elsewhere in West Africa as well. It is believed to have come with that diaspora to Britain,[220] where the government declared it a form of child abuse and said that it could be prosecuted under existing assault laws.[221]

Violence against girl students

In some parts of the world, girls are strongly discouraged from attending school, which some argue is because they fear losing power to women.[222] They are sometimes attacked by members of the community if they do so.[223][224][225][226] In parts of South Asia, girls schools are set on fire by vigilante groups.[227][228] Such attacks are common in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Notable examples include the kidnapping of hundreds of female students in Chibok in 2014 and Dapchi in 2018.

Child marriage

A child marriage is a marriage in which one or both participants are minors, often before the age of puberty. Child marriages are common in many parts of the world, especially in parts of Asia and Africa. The United Nations considers those below the age of 18 years to be incapable of giving valid consent to marriage and therefore regards such marriages as a form of forced marriage; and that marriages under the age of majority have significant potential to constitute a form of child abuse.[229] In many countries, such practices are lawful or — even where laws prohibit child marriage — often unenforced.[230] India has more child brides than other nation, with 40% of the world total.[231] The countries with the highest rates of child marriage are: Niger (75%), Central African Republic and Chad (68%), and Bangladesh (66%).[232]

Bride kidnapping, also known as marriage by abduction or marriage by capture, has been practiced around the world and throughout history, and sometimes involves minors. It is still practiced in parts of Central Asia, the Caucasus region, and some African countries. In Ethiopia, marriage by abduction is widespread, and many young girls are kidnapped this way.[233] In most countries, bride kidnapping, in which a male abducts the female he wants to marry, is considered a criminal offense rather than a valid form of marriage.[234] In many cases, the groom also rapes his kidnapped bride, in order to prevent her from returning to her family due to shame.[235]

Sacred prostitution often involves girls being pledged to priests or those of higher castes, such as the practice of devadasi in South Asia or fetish slaves in West Africa.

Violence against children with superstitious accusations

Customary beliefs in witchcraft are common in many parts of the world, even among the educated. Anthropologists have argued that the disabled are often viewed as bad omens as raising a child with a disability in such communities are an insurmountable hurdle.[236] This is found in Africa[237] and in communities in the Amazon. Children who are specifically at risk include orphans, street-children, albinos, disabled children, children who are unusually gifted, children who were born prematurely or in unusual positions, twins,[238] children of single mothers and children who express gender identity issues.[236] Consequently, those accused of being a witch are ostracized and subjected to punishment, torture and even murdered,[239][240] often by being buried alive or left to starve.[236] For example, in southern Ethiopia, children with physical abnormalities are considered to be ritually impure or mingi, the latter are believed to exert an evil influence upon others, so disabled infants have traditionally been disposed of without a proper burial.[241] Reports by UNICEF, UNHCR, Save The Children and Human Rights Watch have highlighted the violence and abuse towards children accused of witchcraft in Africa.[242][243][244][245] A 2010 UNICEF report describes children as young as eight being burned, beaten and even killed as punishment for suspected witchcraft. The report notes that accusations against children are a recent phenomenon; women and the elderly were formerly more likely to be accused. UNICEF attributes the rise in vulnerable children being abused in this way to increased urbanization and social disruption caused by war.[246]

Ethics

One of the most challenging ethical dilemmas arising from child abuse relates to the parental rights of abusive parents or caretakers with regard to their children, particularly in medical settings.[247] In the United States, the 2008 New Hampshire case of Andrew Bedner drew attention to this legal and moral conundrum. Bedner, accused of severely injuring his infant daughter, sued for the right to determine whether or not she remain on life support; keeping her alive, which would have prevented a murder charge, created a motive for Bedner to act that conflicted with the apparent interests of his child.[247][248][249] Bioethicists Jacob M. Appel and Thaddeus Mason Pope recently argued, in separate articles, that such cases justify the replacement of the accused parent with an alternative decision-maker.[247][250]

Child abuse also poses ethical concerns related to confidentiality, as victims may be physically or psychologically unable to report abuse to authorities. Accordingly, many jurisdictions and professional bodies have made exceptions to standard requirements for confidentiality and legal privileges in instances of child abuse. Medical professionals, including doctors, therapists, and other mental health workers typically owe a duty of confidentiality to their patients and clients, either by law or the standards of professional ethics, and cannot disclose personal information without the consent of the individual concerned. This duty conflicts with an ethical obligation to protect children from preventable harm. Accordingly, confidentiality is often waived when these professionals have a good faith suspicion that child abuse or neglect has occurred or is likely to occur and make a report to local child protection authorities. This exception allows professionals to breach confidentiality and make a report even when children or their parents or guardians have specifically instructed to the contrary. Child abuse is also a common exception to physician–patient privilege: a medical professional may be called upon to testify in court as to otherwise privileged evidence about suspected child abuse despite the wishes of children or their families.[251] Some child abuse policies in Western countries have been criticized both by some conservatives, who claim such policies unduly interfere in the privacy of the family, and by some feminists of the left wing, who claim such policies disproportionally target and punish disadvantaged women who are often themselves in vulnerable positions.[252] There has also been concern that ethnic minority families are disproportionally targeted.[253][254]

Organizations

There are organizations at national, state, and county levels in the United States that provide community leadership in preventing child abuse and neglect. The National Alliance of Children's Trust Funds and Prevent Child Abuse America[255] are two national organizations with member organizations at the state level.

Many investigations into child abuse are handled on the local level by Child Advocacy Centers. Started over 25 years ago at what is now known as the National Children's Advocacy Center[256] in Huntsville, Alabama by District Attorney Robert "Bud" Cramer these multi-disciplinary teams have met to coordinate their efforts so that cases of child abuse can be investigated quickly and efficiently, ultimately reducing trauma to the child and garnering better convictions.[257][258] These Child Advocacy Centers (known as CACs) have standards set by the National Children's Alliance.[259]

Other organizations focus on specific prevention strategies. The National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome focuses its efforts on the specific issue of preventing child abuse that is manifested as shaken baby syndrome. Mandated reporter training is a program used to prevent ongoing child abuse.

NICHD, also known as the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development is a broad organization, but helps victims of child abuse through one of its branches. Through the Child Development and Behavior (CDB) Branch, NICHD raises awareness efforts by supporting research projects to better understand the short- and long-term impacts of child abuse and neglect. They provide programs and observe National Child Abuse Prevention Month every April since 1984. The United States Children's Bureau leads activities for the Month, including the release of updated statistics about child abuse and neglect, candlelight vigils, and fundraisers to support prevention activities and treatment for victims. The Bureau also sponsors a "Blue Ribbon Campaign," in which people wear blue ribbons in memory of children who have died from abuse, or in honor of individuals and organizations that have taken important steps to prevent child abuse and neglect.[260]

See also

- Abuse

- Abusive power and control

- AMBER Alert

- Adverse Childhood Experiences Study

- Child abandonment

- Child abuse in China

- Child abuse in New Zealand

- Child and family services

- Child murder

- Cinderella effect

- Complex post-traumatic stress disorder

- Corporal punishment in the home

- Domestic violence

- Dysfunctional family

- Emotional dysregulation

- Foster Care

- Infanticide

- Isolation to facilitate abuse

- Karly's Law

- Mandatory reporter

- Narcissistic parent

- Orphanage

- Parental bullying of children

- Parental narcissistic abuse

- Reactive attachment disorder

- Residential Child Care Community

- School corporal punishment

- Songs about child abuse

References

- McCoy, M.L.; Keen, S.M. (2013). "Introduction". Child Abuse and Neglect (2 ed.). New York: Psychology Press. pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-1-84872-529-4. OCLC 863824493. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Young-Bruehl, Elisabeth (2012). Childism: Confronting Prejudice Against Children. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17311-6.

- Coghill, D.; Bonnar, S.; Duke, S.; Graham, J.; Seth, S. (2009). Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-19-923499-8. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Wise, Deborah (2011). "Child Abuse Assessment". In Hersen, Michel (ed.). Clinician's Handbook of Child Behavioral Assessment. Academic Press. p. 550. ISBN 978-0-08-049067-0. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Leeb, R.T.; Paulozzi, L.J.; Melanson, C.; Simon, T.R.; Arias, I. (January 2008). Child Maltreatment Surveillance: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0 (PDF). Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2017.

- Conley, Amy (2010). "2. Social Development, Social Investment, and Child Welfare". In Midgley, James; Conley, Amy (eds.). Social Work and Social Development: Theories and Skills for Developmental Social Work. Oxford University Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0-19-045350-3. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Bonnie S. Fisher; Steven P. Lab, eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of Victimology and Crime Prevention. Sage Publications. pp. 86–92. ISBN 978-1-4522-6637-4. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "What is Child Abuse and Neglect?". Australian Institute of Family Studies. September 2015. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015.

- Mehnaz, Aisha (2013). "Child Neglect: Wider Dimensions". In RN Srivastava; Rajeev Seth; Joan van Niekerk (eds.). Child Abuse and Neglect: Challenges and Opportunities. JP Medical Ltd. p. 101. ISBN 978-9350904497. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017.

Many do not consider neglect a kind of abuse especially in a condition where the parents are involved as it is often considered unintentional and arise from a lack of knowledge or awareness. This may be true in certain circumstances and often it results in insurmountable problem being faced by the parents.

- Friedman, E; Billick, SB (June 2015). "Unintentional child neglect: literature review and observational study". Psychiatric Quarterly. 86 (2): 253–9. doi:10.1007/s11126-014-9328-0. PMID 25398462.

[T]he issue of child neglect is still not well understood, partially because child neglect does not have a consistent, universally accepted definition. Some researchers consider child neglect and child abuse to be one in the same [sic], while other researchers consider them to be conceptually different. Factors that make child neglect difficult to define include: (1) Cultural differences; motives must be taken into account because parents may believe they are acting in the child's best interests based on cultural beliefs (2) the fact that the effect of child abuse is not always immediately visible; the effects of emotional neglect specifically may not be apparent until later in the child's development, and (3) the large spectrum of actions that fall under the category of child abuse.

- "Child abuse and neglect by parents and other caregivers" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Herrenkohl RC (2005). "The definition of child maltreatment: from case study to construct". Child Abuse and Neglect. 29 (5): 413–24. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.002. PMID 15970317.

- "Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect in Federal Law". childwelfare.gov. Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- World Health Organization and International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (2006). "1. The nature and consequences of child maltreatment" (PDF). Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva, Switzerland. ISBN 978-9241594363.

- Noh Anh, Helen (1994). "Cultural Diversity and the Definition of Child Abuse", in Barth, R.P. et al., Child Welfare Research Review, Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 28. ISBN 0-231-08074-3

- "Corporal Punishment" Archived 31 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. 2008.

- Durrant, Joan; Ensom, Ron (4 September 2012). "Physical punishment of children: lessons from 20 years of research". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 184 (12): 1373–1377. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101314. PMC 3447048. PMID 22311946.

- Saunders, Bernadette; Goddard, Chris (2010). Physical Punishment in Childhood: The Rights of the Child. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-470-72706-5.

- Pinheiro, Paulo Sérgio (2006). "Violence against children in the home and family" (PDF). World Report on Violence Against Children. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Secretary-General's Study on Violence Against Children. ISBN 978-92-95057-51-7. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016.

- Theoklitou D, Kabitsis N, Kabitsi A (2012). "Physical and emotional abuse of primary school children by teachers". Child Abuse Negl. 36 (1): 64–70. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.007. PMID 22197151.

- "Alice Miller – Child Abuse and Mistreatment". Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "Effects of child abuse and neglect for adult survivors". 16 June 2014. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- "Child Sexual Abuse". Medline Plus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013.