Birth control in Africa

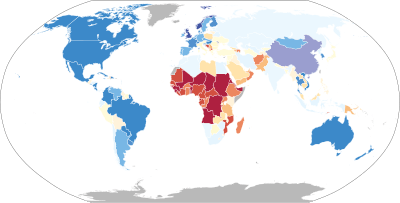

Most of the countries with the lowest rates of contraceptive use; highest maternal, infant, and child mortality rates; and highest fertility rates are in Africa.[1][2][3][4][5]

|

6%

12%

18%

24%

|

36%

48%

54%

60%

|

66%

78%

86%

No data

|

Approximately 30% of all women use birth control, although over half of all African women would use birth control if it were available.[6][7] The main problems that prevent access to and use of birth control are unavailability (especially among young people, unmarried people, and the poor), limited choice of birth control methods, side-effects or fear or side-effects, spousal disapproval or other gender-based barriers, religious concerns, and bias from healthcare providers.[7] [8] There is evidence that increased use of family planning methods decreases maternal and infant mortality rates, improves quality of life for mothers, and stimulates economic development.[9][10][11][12]

Public policies and cultural attitudes play a role in birth control prevalence.[13][14][15][16]

Prevalence

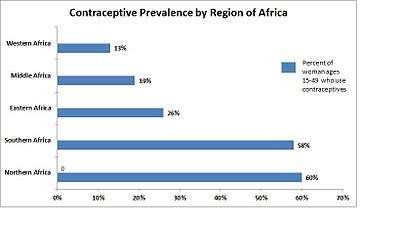

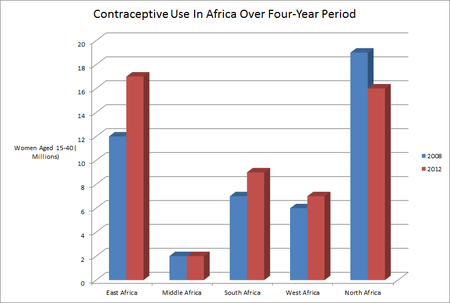

In Africa, 24% of women of reproductive age have an unmet need for modern contraception.[7] Rwanda and Uganda have the highest unmet need for contraception rates.[17] In Uganda, NGOs are trying to make contraceptives more available in rural areas.[18] According to a study done by Nwachukwu and Obasi in Nigeria in 2008, modern birth control methods were used by 30% of respondents. [19] The Demographic Health Survey (DHS) of 2013 revealed that a mere two percent of sexually active girls between 15 and 19 use contraceptives. Thus, It is not surprising that 23% of the girls in this age group have children.[20]

Namibia, with a contraception use rate of 46% in 2006-07, has one of the highest rates in Africa, while Senegal with a rate of 8.7% in 2005 has one of the lowest.[21] In Sub-Saharan Africa, extreme poverty, lack of access to birth control, and restrictive abortion laws cause about 3% of women to have unsafe abortions.[22][23] South Africa, Botswana, and Zimbabwe have successful family planning programs, but other central and southern African countries continue to encounter difficulties in achieving higher contraceptive prevalence and lower fertility rates.[24] Contraceptive use among women in Sub-Saharan Africa has risen from about 5% in 1991 to about 30% in 2006.[6] Socioeconomic class constitutes an inequity in relation to mortality and morbidity. [25] The disparity between the rich and poor in the use of contraception has remained the same despite overall improvements in socioeconomic status and expansion of family planning services.

Factors affecting prevalence

A growing population, limited access to contraception, limited available choices for type of contraception, cultural and religious opposition, poor quality of available services, and gender-based barriers, all contribute to the high "unmet need" for contraception in Africa.[7] In Eastern Africa, the unmet need is attributed to socioeconomic variables, the family planning program environment and reproductive behavior models. [26] Gyimah attributes the higher fertility rates of Sub-Saharan African countries compared to other developing countries to “the inter-related factors of early childbearing, high infant mortality, low education and contraceptive use, and persistence of high fertility-sustaining social customs.”[9]

Some of the factors identified that prevented use of modern birth control methods in a 2008 study in Nigeria were “perceived negative health reaction, fear of unknown effects, cost, spouse’s disapproval, religious belief and inadequate information.” [19] According to “Equity Analysis: Identifying Who Benefits from Family Planning Programs,” the main factors that contribute to unavailability of family planning information and modern birth control methods are low education level, young age, and living in a rural area.[27] A 1996 study that included couples in both urban and rural Kenya who did not want have a child, yet were not using birth control, found additional factors that limited birth control use to be traditional practices, such as "naming relatives" and a preference for sons who can give parents more financial security as they age.[28]

Until the 1990s, contraception and family planning were associated with fears of eugenic ideology and population control, which narrowed the scope of behavior-change communication and distribution of contraceptive devices.[29] Recently, a new approach of promoting spousal discussion of contraception has been proposed as a policy strategy to narrow the gender gap in partners' fertility intentions in developing countries.[8] Men are usually the decision makers on birth control use, and therefore should be the targeted audience of educational campaigns.[19] Discussion between spouses is expected to increase contraceptive use, because one reason women cite for not using contraception is their husband's disapproval, despite never having discussed family planning with them.[8]

A 2013 study in Kenya and Zambia shows a correlation between ante-natal care use and post-partum contraceptive use which suggests that contraceptive use could be increased by promoting ante-natal care services.[30] A 1996 study in Zambia again cites the importance of educating both men and women and states that single mothers and teenagers should be the primary focus of birth control education. Of the 376 women recruited after giving birth at a hospital, 34% had previously used family planning, and 64% had used family planning a year after giving birth. Of the women who did not use family planning, 39% cited spousal disapproval as the reason. 84% of single mothers had never used family planning before and 56% of teenagers did not know anything about family planning.[31] A 1996 Kenyan study suggests modern contraception education that promotes quality of life over "traditional reproductive practices."[28]

Methods

In most African countries, only a few types of birth control are offered, which makes finding a method that fits a couple's reproductive needs difficult.[32] Many African countries had low access scores on almost every method.[32] In the 1999 ratings for 88 countries, 73% of countries offered condoms to at least half their population, 65% of countries offered the pill, 54% offered IUDs, 42% offered female sterilization, and 26% offered male sterilization.[32] Low levels of condom use are cause for concern, particularly in the context of generalized epidemics in Sub-Saharan Africa.[33] The use rate for injectable contraceptives increased from 2% to 8%, and from 8% to 26% in Sub-Saharan Africa, while the rate for condoms was 5%–7%.[34] The least used method of contraception is male sterilization, with a rate of less than 3%.[34] 6%–20% of women in Sub-Saharan Africa used injectable contraceptives covertly, a practice more common in areas where contraceptive prevalence was low, particularly rural areas.[35]

Effects

Use of modern birth control methods has been shown to decrease female fertility rate in Sub-Saharan Africa.[36]

Health

Africa has the highest maternal death rate, which measures the death rate of women due to pregnancy and childbirth.[37] The maternal mortality ratio in Sub Saharan Africa is 1,006 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.[38] An article by Baggaley et al. suggests that increasing access to safe abortion would reduce maternal mortality due to unsafe abortions in Ethiopia and Tanzania.[39] Alvergne et al. argue in “Fertility, parental investment, and the early adoption of modern contraception in rural Ethiopia” that an increase in usage of family planning increases birth spacing which consequently decreases infant mortality, although it had no observed effect on overall child mortality, possibly due to a recent overall decrease childhood death rates among both contraception users and nonusers.[10]

Additionally, increasing condom use in Africa would decrease rates of HIV transmission.[40]

Social

According to Gyimah, women who have their first child at a younger age are less likely to finish school and will be more limited to low-paying career options.[9] Research suggests that desire to continue with their education is one of the largest reasons that women use birth control and terminate pregnancies.[41][42] Since birth control is not widely available, beginning a family at a young age is additionally correlated with a higher overall fertility rate.[9] Alvergne suggests that another benefit of longer birth intervals due to contraception use is an increase in parental investment and proportion of resources dedicated to each child.[10] Two of the most prevalent reasons for married women to use birth control are to plan birth spacing and postpone pregnancies to achieve their desired family size.[43]

According to Gyimah, fertility rates are declining in some African countries, particularly Kenya, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Ghana.[9] The decrease in fertility rates in Ghana is largely attributed to investment in education that has caused an increase in age at first birth and improved job opportunities for women.[9]

Economic

Increased use of family planning leads to economic development because women are more likely to work and their children are more likely to be healthy and educated.[44] There is an estimated 140%-600% return on investment in family planning methods due to health care savings and economic development.[11][12] "The Economic Case for Birth Control," published in 1967, argues that decreasing the birth rate in countries with high fertility levels is crucial to economic growth and that "one dollar useed to slow population growth can be 100 times more effective in raising income per head than one dollar to expand output."[45]

Since the majority of African countries have high fertility rates relative to the rest of the world, it is clear that most African countries have not undergone a demographic transition. In other parts of the world, there is evidence that economic growth increases after a country undergoes demographic transition.[46] This is due to more women working, greater parental investment in children in terms of education and attention, and longer, more productive working life due to health improvements. Although other improvements in public health are necessary to fully undergo a demographic transition, it can not occur without family planning. It is unclear, however, how exactly the demographic transition will affect society in sub-Saharan Africa.[47]

An economic downside to using birth control to limit fertility is the possibility that parents will not having enough successful, living offspring to support them financially in old age. This is a significant concern among parents.[48]

Society and culture

Public policy

The United Nations created the "Every Woman Every Child" initiative to assess the progress toward meeting women's contraceptive needs and modern family planning services.[13] These initiatives have set their goals in expected increases in the number of users of modern methods because this is a direct indicator that typically increases in response to interventions.[13] The London Summit on Family Planning is attempting to make modern contraceptive services accessible to an additional 120 million women in the world's poorest 69 countries by the year 2020.[13] The summit wants to eradicate discrimination or coercion against girls who seek contraceptives.[13]

One of the Millennium Development Goals is improving maternal health.[14] The maternal mortality ratio in developing regions is 15 times higher than in the developed regions.[14] The maternal health initiative calls for countries to reduce their maternal mortality rate by three quarters by 2015.[14] Eritrea is one of the four African countries on track to achieve Millennium Development Goals,[14] which would be a rate of less than 350 deaths per 100,000 births.

Cultural attitudes

In the traditional northern Ghana society, payment of bridewealth in cows and sheep signifies the wife's obligation to bear children. This deeply ingrained expectation about a woman’s duty to reproduce creates apprehension in men that their wife or wives may be unfaithful if they use contraception.[49] Arranged marriages, which generally occur at a young age, limit female autonomy and therefore often result in a culture in which females do not feel in control of their reproductive health.[50] According to a 1987 study by Caldwell, large families are seen as socially favorable and infertility is viewed negatively, causing women to use birth control mainly to increase birth intervals instead of limiting family size.[48] The possibility that women may act independently is also regarded as a threat to the strong patriarchal tradition. Physical abuse and reprisals from the extended family pose substantial threats to women. Violence against women was considered justified by 51% of female and 43% of male respondents if the wife used a contraceptive method without the husband's knowledge.[15] Women feared that their husband's disapproval of family planning could lead to withholding of affection or sex or even divorce.

In areas with communal grazing areas or “tribal tenure,” large families are desirable because more children means more productive capability and therefore higher status and more wealth for the father, according to Boserup. Additionally, having more children decreases the mother’s workload. However, most people in Africa today live in urban areas or agricultural communities with private land ownership. In these communities, having a family that is larger than one can support is viewed negatively. Private landowners do not need to rely on financial support from children in old age or in crises because they can sell their land. Despite these changes Boserup suggests that large families are still seen as symbols of wealth and higher social status by men.[51]

In the cities of Nairobi and Bungoma in Kenya, major barriers to contraceptive use included lack of agreement on contraceptive use and on reproductive intentions. There were also gaps in knowledge on contraceptive methods, fears from rumors, misconceptions about specific methods, perceived undesirable effects and availability and poor quality of services in the areas studied. About 33% of wives in Nairobi and 50% in Bungoma desired no more children; husbands desired about four or more children than wives wanted.[52] Lack of couple agreement and communication were primary reasons for nonuse. Compared to Ghana, the man is considered the decision maker. The husband has a greater desire for more children, preferably sons, because they are able to provide financial security for their parents.

In other Sub-Saharan African cultures, spousal discussion of sexual matters is discouraged. Friends of family and in-laws are used between partners for them to exchange ideas and issues pertaining to this matter.[53] Couples in these cultures may use other forms of communication — such as specific music, wearing specific waist beads, acting a certain way, and preparing favorite meals — to convey unambiguous sex-related messages to each other.[53] In the case of contraception, a man's use of a contraceptive may itself be a nonverbal indicator of approval.[53] Therefore, discussion may improve knowledge of family planning attitudes only when it is more efficient than, or augments the effectiveness of, other forms of communication.[53]

References

- "Birth Rate". World Bank. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- "Contraceptive prevalence". World Bank. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- "Maternal mortality ratio". World Bank. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- "Fertility rate". World Bank. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- "Mortality rate, under-5". World Bank. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- Cleland, J. G.; Ndugwa, R. P.; Zulu, E. M. (2011). "Family planning in sub-Saharan Africa: Progress or stagnation?". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 89 (2): 137–143. doi:10.2471/BLT.10.077925. PMC 3040375. PMID 21346925.

- "Family planning/Contraception WHO Fact Sheet". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- DeRose, Laurie; Nii-Amoo Dodoo; Alex C. Ezeh; Tom O. Owuor (June 2004). "Does Discussion of Family Planning Improve Knowledge of Partner's Attitude Toward Contraceptives?". Guttmacher Institute.

- Gyimah, Stephen Obeng (June 2003). "A Cohort Analysis of the Timing of First Birth and Fertility in Ghana". Population Research and Policy Review. 22 (3): 251–266. doi:10.1023/A:1026008912138.

- Alvergne, A; Lawson, D. W.; Clarke, P. M.R.; Gurmu, E.; Mace, R. (2013). "Fertility, parental investment, and the early adoption of modern contraception in rural ethiopia". American Journal of Human Biology. 25 (1): 107–115. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22348. PMID 23180659.

- Carr, Bob; Melinda French Gates; Andrew Mitchell; Rajiv Shah (14 July 2012). "Giving women the power to plan their families". The Lancet. 380 (9837): 80–82. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60905-2. PMID 22784540. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "222 Million Women Have Unmet Need for Modern Family Planning". The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Susheela Singh; Jacqueline E. Darroch (June 2012). "Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Contraceptive Services Estimates for 2012" (PDF). Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), 201.

- "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". UN Web Services Section, Department of Public Information.

- Bawah, AA; Akweongo P; Simmons R; Phillips JF (30 Mar 1999). "Women's fears and men's anxieties: the impact of family planning on gender relations in northern Ghana". Studies in Family Planning. 30 (1): 54–66. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00054.x. hdl:2027.42/73927. PMID 10216896.

- May, John F. (2017). "The Politics of Family Planning Policies and Programs in sub-Saharan Africa". Population and Development Review. 43 (S1): 308–329. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00165.x. ISSN 1728-4457.

- "Unmet need for contraception". The World Bank.

- Eric Wakabi and Joan Esther Kilande (23 June 2017). "Make contraceptives available". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 15 August 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Nwachukwu, Ike; O. O. Obasi (April 2008). "Use of Modern Birth Control Methods among Rural Communities in Imo State, Nigeria". African Journal of Reproductive Health. 12 (1): 101–108.

- Damilola Oyedele (8 August 2017). "Face the truth". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Low use of contraception among poor women in Africa: an equity issue". WHO. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- Rasch, V. (2011). "Unsafe abortion and postabortion care - an overview". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 90 (7): 692–700. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01165.x. PMID 21542813.

- Huezo, C. M. (1998). "Current reversible contraceptive methods: A global perspective". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 62 Suppl 1: S3–15. doi:10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00084-8. PMID 9806233.

- Lucas, D. (1992). "Fertility and family planning in southern and central Africa". Studies in Family Planning. 23 (3): 145–158. doi:10.2307/1966724. JSTOR 1966724. PMID 1523695.

- Creanga, Andreea A; Duff Gillespie; Sabrina Karklins; Amy O Tsu (2011). "Low use of contraception among poor women in Africa: an equity issue". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 89 (4): 258–266. doi:10.2471/BLT.10.083329. PMC 3066524. PMID 21479090.

- Sharan, Mona; Saifuddin Ahmed; John May; Agnes Soucat (2009). "Family Planning Trends in Sub-Saharan Africa: Progress, Prospects, and Lessons Learned" (PDF). World Bank: 445–469. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- Ortayli, N; S Malarcher (2010). "Equity Analysis: Identifying Who Benefits from Family Planning Programs". Studies in Family Planning. 41 (2): 101–108. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00230.x. PMID 21466109.

- Kamau, RK; Karanja J; Sekadde-Kigondu C; Ruminjo JK; Nichols D; Liku J (October 1996). "Barriers to contraceptive use in Kenya". East African Medical Journal. 73 (10): 651–659. PMID 8997845.

- The Global Family Planning Revolution (PDF). World Bank. 2007. ISBN 978-0-8213-6951-7.

- Do, M; Hotchkiss D (4 January 2013). "Relationships between antenatal and postnatal care and post-partum modern contraceptive use: evidence from population surveys in Kenya and Zambia". BMC Health Services Research. 13 (6): 6. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-6. PMC 3545900. PMID 23289547.

- Susu, B; Ransjö-Arvidson AB; Chintu K; Sundström K; Christensson K (November 1996). "Family planning practices before and after childbirth in Lusaka, Zambia". East African Medical Journal. 73 (11): 708–713. PMID 8997858.

- Ross, John; Karen Hardee; Elizabeth Mumford; Sherrine Eid (March 2002). "Contraceptive Method Choice in Developing Countries". Guttmacher Institute. 28 (1).

- Caldwell, John; Caldwell Pat (December 2003). "Africa: the new family planning frontier". Studies in Family Planning. 33 (1): 76–86. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00076.x. PMID 11974421.

- Seiber, Eric; Jane T. Bertrand; Tara M.Sullivan (September 2007). "Changes in Contraceptive Method Mix In Developing Countries". Guttmacher Institute. 33 (3).

- Sinding, S (2005). "Does 'CNN' (condoms, needles, negotiation) work better than 'ABC' (abstinence, being faithful and condom use) in attacking the AIDS epidemic?". International Family Planning Perspectives. 31 (1): 38–40. doi:10.1363/ifpp.31.38.05. PMID 15888408.

- Ijaiya, GT; Raheem UA; Olatinwo AO; Ijaiya MD; Ijaiya MA (December 2009). "Estimating the impact of birth control on fertility rate in sub-Saharan Africa". African Journal of Reproductive Health. 13 (4): 137–145. PMID 20690281.

- "Population, Family Planning, and the Future of Africa". WorldWatch Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-10-16. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- Rao, Chalapati; Alan D. Lopez; Yusuf Hemed (2006). Jamison DT; Feachem RG; Makgoba MW; et al. (eds.). Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa (2 ed.). Washington D.C.: World Bank. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Baggaley, R. F.; J Burgin; O R Campbell (2010). "The Potential of Medical Abortion to Reduce Maternal Mortality in Africa: What Benefits for Tanzania and Ethiopia?". PLOS ONE. 5 (10): e13260. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013260. PMC 2952582. PMID 20948995.

- Presser, Harriet B; Megan L. Klein Hattori; Sangeeta Parashar; Sara Raley; Zhihong Sa (September 2006). "Demographic change and response: Social context and the practice of birth control in six countries". Journal of Population Research. 23 (2): 135–163. doi:10.1007/bf03031813.

- Nichols, Douglas; Emile T. Woods; Deborah S. Gates; Joyce Sherman (May–June 1987). "Sexual Behavior, Contraceptive Practice, and Reproductive Health Among Liberian Adolescents". Studies in Family Planning. 18 (3): 169–176. doi:10.2307/1966811. JSTOR 1966811.

- Ware, Helen (November 1976). "Motivations for the Use of Birth Control: Evidence from West Africa". Demography. 13 (4): 479–493. doi:10.2307/2060504. JSTOR 2060504.

- Timæus, Ian M; Tom A. Moultrie (3 September 2008). "On Postponement and Birth Intervals" (PDF). Population and Development Review. 34 (3): 483–510. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00233.x.

- Canning, David; T Paul Schultz (14 July 2012). "The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning". The Lancet. 380 (9837): 165–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60827-7. PMID 22784535. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Enke, Stephen (1 May 1967). "The Economic Case for Birth Control in Underdeveloped Nations". Challenge: 30. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Galor, Oded (April–May 2005). "The Demographic Transition and the Emergence of Sustained Economic Growth" (PDF). Journal of the European Economic Association. 3 (2/3): 494–504. doi:10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.494. hdl:10419/80187.

- Reher, David S (11 January 2011). "Economic and Social Implications of the Demographic Transition". Population and Development Review. 37: 11–33. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00376.x.

- Caldwell, John C.; Pat Caldwell (3 September 1987). "The Cultural Context of High Fertility in sub-Saharan Africa". Population and Development Review. 13 (3): 409–437. doi:10.2307/1973133. JSTOR 1973133.

- Kwapong, Olivia (3 November 2008). "The health situation of women in Ghana". Rural and Remote Health. 8. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Coale, Ansley (3 August 1992). "Age of Entry into Marriage and the Date of the Initiation of Voluntary Birth Control". Demography. 29 (3): 333–341. doi:10.2307/2061821. JSTOR 2061821.

- Boserup, Ester (3 September 1985). "Economic and Demographic Interrelationships in sub-Saharan Africa". Population and Development Review. 11 (3): 383–397. doi:10.2307/1973245. JSTOR 1973245.

- Rutenberg, N; Watkins SC (Oct 1997). "The buzz outside the clinics: conversations and contraception in Nyanza Province, Kenya". Stud Fam Plann. 28 (4): 290–307. doi:10.2307/2137860. JSTOR 2137860. PMID 9431650.

- Laurie F. DeRose; F. Nii-Amoo Dodoo; Alex C. Ezeh; Tom O. Owuor (2004). "Does Discussion of Family Planning Improve Knowledge Of Partner's Attitude Toward Contraceptives?" (PDF). International Family Planning Perspectives. 30 (2): 87–93. doi:10.1363/3008704. PMID 15210407.