Reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance

Reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance (RISUG), formerly referred to as the synthetic polymer styrene maleic anhydride (SMA), is the development name of a male contraceptive injection developed at IIT Kharagpur in India by the team of Dr. Sujoy K. Guha. Phase III clinical trials are underway in India, slowed by insufficient volunteers.[1] It has been patented in India, China, Bangladesh, and the United States.[1] A method based on RISUG, Vasalgel, is currently under development in the US. However there has been little or no progress in terms of bringing the product to market.[2]

Mechanism of action

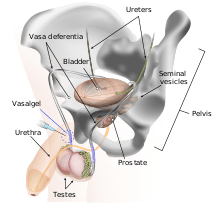

RISUG works by an injection into the vas deferens, the vessel through which the sperm moves before ejaculation. RISUG is similar to vasectomy in that a local anesthetic is administered, an incision is made in the scrotum, and the vasa deferentia are injected with a polymer gel (rather than being cut and cauterized).[3] In a matter of minutes, the injection coats the walls of the vasa with a clear gel made of 60 mg of the copolymer styrene/maleic anhydride (SMA) with 120 µl of the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide. The copolymer is made by irradiation of the two monomers with a dose of 0.2 to 0.24 megarad for every 40 g of copolymer and a dose rate of 30 to 40 rad/s. Dr P.Jha a Senior scientist worked on Effect of gamma dose rate and total dose interrelation on molecular designing and biological function of polymer [4] The source of irradiation is cobalt-60 gamma radiation.

The effect the chemical has on sperm is not completely understood. Originally it was thought that it lowered the pH of the environment enough to kill the sperm.[5] More recent research claims that this is not enough to explain the effect.

Professor S. K. Guha theorizes that the polymer surface has a negative and positive electric charge mosaic. Within an hour after placement the differential charge from the gel will rupture the sperm's cell membrane as it passes through the vas, deactivating it before it can exit from the body.[6]

Development

Sujoy K. Guha developed RISUG after years of developing other inventions. He originally wanted to create an artificial heart that could pump blood using a strong electrical pulse. Using the 13-chamber model of a cockroach heart, he designed a softer pumping mechanism that would theoretically be safe to use in humans. As India's population grew throughout the 1970s, Guha modified his heart pump design to create a water pump that could work off of differences in ionic charges between salt water and fresh water in water treatment facilities. This filtration system did not require electricity and could potentially help large groups of people have access to clean water. India however decided that the population problem would be better served by developing more effective contraception. So Guha again modified his design to work safely inside the body, specifically inside the male genitalia. The non-toxic polymer of RISUG also uses differences in the charges of the semen to rupture the sperm as it flows through the vas deferens.[7]

Intellectual property rights to RISUG in the United States were acquired between 2010–2012 by the Parsemus Foundation, a not-for-profit organization, which has branded it as Vasalgel.[8][9] Vasalgel, which has a slightly different formulation than RISUG, is currently undergoing successful animal trials in the United States. Initially, it was hoped that human trials would commence by the end of 2013 and become available to within a few years,[10] but the Parsemus Foundation has encountered delays, and human clinical trials have yet to be initiated.[11]

Advantages

Some of the advantages, according to Dr. Guha, are:

- Effectiveness - There has been only one unplanned pregnancy among partners of the 250 volunteers who have been injected RISUG — apparently due to an improperly administered injection. Out of the 250 volunteers who have been injected RISUG, 15 received the injection more than 10 years ago.

- Convenience - There is no interruption before the sexual act.

- Cost - The shot itself costs less than the syringe used to administer it, and its long term effectiveness would make it theoretically only a four or five time cost, in the entire lifetime of someone who chose to continue to be on it.

- Outpatient procedure - Patients can leave the hospital immediately after an injection and resume their normal sex lives within a week.

- Duration of effect - According to Dr. Guha, a single 60 mg injection can be effective for at least 10 years.

- Reduced side effects - After testing RISUG on more than 250 volunteers, neither Guha nor other researchers in the field report have reported any adverse side effects other than a slight scrotal swelling in some men immediately following the injection which goes away after a few weeks. [12] Because semen, including inactive sperm, still exits the body following ejaculation, patients do not experience the pressure or granulomas that sometimes result after a vasectomy procedure.[3]

- Reversibility - The contraceptive action appears to be completely reversible by flushing the vas deferens with an injection of dimethyl sulfoxide or sodium bicarbonate solution. (The sodium bicarbonate solution cannot be used as the solvent in the initial injection since it would neutralize the positive charge effect). Although this reversal procedure has been tried only on non-human primates, it has been repeatedly successful. Unlike in a vasectomy (see blood-testis barrier), the vas deferens is not completely blocked, the body does not have to absorb the blocked sperm, and sperm antibodies are not produced in large numbers, making successful reversal much more likely than with a vasovasostomy.

Potential hazards

The thoroughness of carcinogenicity, teratogenicity, and toxicity testing in clinical trials has been questioned. In October 2002, India's Ministry of Health aborted the clinical trials due to reports of albumin in urine and scrotal swelling in Phase III trial participants.[13] Although the ICMR has reviewed and approved the toxicology data three times, WHO and Indian researchers say that the studies were not done according to recent international standards. Due to the lack of any evidence for adverse effects, trials were restarted in 2011.[7]

Smart RISUG

Smart RISUG is a newer version of the male contraception that was published in 2009. This polymer adds iron oxide and copper particles to the original compound, giving it magnetic properties and the name “Smart” RISUG. After injection the exact location of the polymer inside the vas deferens can be measured and visualized by X-ray and magnetic imaging. The polymer location can also be externally controlled using a pulsed magnetic field. With this magnetic field, the polymer can change location inside the body to maximize sterility or can be removed to restore fertility. The polymer has magnetoelastic behavior that allows it to stretch and elongate to better line the vas deferens. The iron oxide component is necessary to prevent agglomeration. With the original RISUG polymer, the SMA can possibly clump as a reaction to neighboring proteins. With the presence of iron particles, the polymer has lower protein binding and therefore prevents agglomeration. This makes Smart RISUG safer for the user as it will not accidentally block the vas deferens. The copper particles in the compound allow the polymer to conduct heat. When an external microwave applies heat to the polymer, it can liquify the polymer again to be excreted to restore fertility. Smart RISUG is therefore a better choice for men who want to use RISUG as temporary birth control, since it does not require a second surgery to restore fertility. The addition of metal ions also increases the effectiveness of the spermicide. The low frequency electromagnetic field disintegrates the sperm cell membrane in the head region. This in turn causes both acrosin and hyaluronidase enzymes to leak out of the sperm, making the sperm infertile. The safety of Smart RISUG is still being investigated. With literature research, the spermicidal properties of the compound should not have negative effects on the lining of the vas deferens. The albino rats used to develop the new polymer have not had any adverse symptoms.[14]

References

- Jyoti, Archana (2011-01-03). "Poor response from male volunteers hits RISUG clinical trial". The Pioneer. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- Gifford, Bill (2011-04-26). "The Revolutionary New Birth Control Method for Men". Wired. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- "Expanding Options for Male Contraception". Planned Parenthood Advocates of Arizona. 2011-08-08. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- Jha, Pradeep K., Rakhi Jha, B. L. Gupta, and Sujoy K. Guha. "Effect of γ-dose rate and total dose interrelation on the polymeric hydrogel: A novel injectable male contraceptive." Radiation Physics and Chemistry 79, no. 5 (2010): 663-671.

- Archived March 17, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "RISUG". MaleContraceptives.org. 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- Gifford, Bill (2011-04-26). "The Revolutionary New Birth Control Method for Men". Wired. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- Beck, Melinda (2011-06-14). "'Honey, It's Your Turn...'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- "Parsemus Foundation". Parsemusfoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-14. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- "Male Birth Control is Here! It's Safe, Cheap, and Lasts for a Decade".

- http://www.parsemusfoundation.org/vasalgel-faqs/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-03. Retrieved 2014-11-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Country's first male contraceptive aborted | News | Population". Infochangeindia.org. 2002-10-24. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- Jha, R. K.; Jha, P. K.; Guha, S. K.; Guha, Sujoy (2013-03-25). "Smart RISUG: A potential new contraceptive and its magnetic field-mediated sperm interaction". International Journal of Nanomedicine. Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 4: 55–64. doi:10.2147/ijn.s4818. PMC 2720737. PMID 19421370.

External links

- U.S. Patent 5,488,075

- Information on Vasalgel and RISUG from Male Contraception Initiative (also includes journal article refs and videos)

- Detailed information from Male contraceptives.org

- ICMR Website

- ICMR 2004 Annual Report