Tracing Contacts

RITE (Rapid Isolation and Treatment of Ebola) team members take a canoe as the last leg of their day-long journey to a remote village with suspected Ebola cases.

David Blackley, CDC responder, prepares to board a U.S. Army helicopter to travel to a remote village in Liberia as part of a RITE (Rapid Isolation and Treatment of Ebola) team.

Contact tracing is a key part of this outbreak. Because the natural reservoir host of Ebola has not yet been identified, we don’t know for sure how the virus spreads to humans at the start of an outbreak. However, scientists believe that the first patient becomes infected through some kind of contact with an infected animal, such as a fruit bat or primate (apes and monkeys). Person-to-person transmission follows and can lead to large numbers of cases.

Experience has taught us that rapid case finding, paired with proper infection control, is critical to stop the spread of Ebola. CDC and partners are using contact tracing to identify new Ebola cases quickly, which increases patients’ chances of survival, and to isolate patients as soon as they show symptoms, which prevents spread to others. Even one missed contact can mean Ebola will continue to spread because sick people need care from others. Contact tracing works—it’s been used in each of the previous 20 Ebola outbreaks over the past 40 years to successfully control Ebola. During this outbreak, success stories from Mali, Nigeria, and Senegal have shown how effective contact tracing can be in containing outbreaks.

"You’ll see that over the past 20 years, if infected people are removed from the community within the first two or three days of the disease, you can stop the chain of transmission."

– Pierre Rollin, Deputy Branch Chief, Viral Special Pathogens Branch, CDC

Kari Yacisin heads to a remote village in Guinea to complete a day of contact tracing with her team.

Stories from the Field

Contact tracing is the laborious job of finding all those who came into contact with an Ebola patient and checking them for symptoms every day for 21 days. It is slow, painstaking work, but Kari Yacisin, a CDC responder who was deployed to Guinea, knows that effective contact tracing can make a difference. If any of these contacts turn out to be infected, their contacts have to be traced as well—and so on, until the outbreak is contained. The number of contacts can be daunting, especially if the patient isn’t recognized quickly and separated from other people.

“We must continue educating the community, maintaining relationships and building trust within the community to get control of this outbreak.” said Kari.

Neil Vora prepares for the two-and-half hour drive to Bomi County in Liberia.

Ambulance chasing is a discouraged practice in the United States—but in Liberia it’s exactly what Neil Vora, a CDC responder, had to do as part of his efforts to stop the spread of Ebola at its source.

“We would follow ambulances that were called to pick up patients with suspected Ebola cases. We would keep our distance and observe how they collected patients and would make corrections to any lapse in infection control. As soon as the ambulance left we would start the contact tracing investigation,” said Neil. Neil recently returned from a month working in Liberia, during which time he was based in Bomi County, a rural area about two hours away from Liberia’s capital.

Rapidly identifying contacts of patients with Ebola is a key component to stopping the spread of the virus. Each patient with Ebola can have 10 or more contacts, all of whom need to be monitored for 21 days. “If you skip just one day, it might be the day the contact comes down with Ebola and a whole new chain of Ebola transmission can start all over again,” Neil said.

More than 100 Ebola cases were identified in Bomi County, and while Neil was there, he helped local health officials monitor the hundreds of contacts from all of these Ebola cases.

CDC RITE (Rapid Isolation and Treatment of Ebola) team members would camp in rural communities for several days during their outbreak investigation. This picture shows their office in the field.

Several factors contributed to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, and it has taken a large number of partners and strategies to help get it under control.

Among these factors are health systems that were not prepared for an influx of Ebola cases and that had limited knowledge of the virus and its symptoms. Outbreaks in crowded urban centers also constantly seeded new outbreaks in remote areas. Satish Pillai, a CDC medical officer, was sent to Liberia to help solve some of these problems as part of a RITE (Rapid Isolation and Treatment of Ebola) team.

RITE teams are mobilized to respond to remote villages and towns following reports of Ebola cases by local and county health officials. Their goal: stop the chain of Ebola transmission.

“Cases of Ebola in Liberia were showing up in remote areas. In many instances, someone who contracted Ebola in the capital city of Monrovia brought it back to their community,” said Satish. “This led to sustained transmission of the virus that was hard to stop because it was so difficult to reach these communities.” RITE teams not only work on active case finding and contact tracing but also identify the basic sanitation and food needs in communities.

“One of the communities we visited was banned from the closest market because of Ebola fears. We called in the World Food Program to help. Another community had broken water pumps and could not access safe water. We found partners that could fix the pump,” Satish said.

Dan Martin (center) crosses a river in Sierra Leone on a human-powered ferry with colleagues Mohamed Okala Sankoh and James Fornah. One Land Cruiser, one motorcycle, and about a dozen people were pulled across this river.

Dan Martin, a CDC responder deployed for a month to Sierra Leone, said that the shadow of Ebola was constantly present during his time there. His job involved frequent contact with local health workers as he helped them improve their ability to detect, investigate, and follow up on cases.

“We’re learning in this outbreak that Ebola is not always a death sentence. We’re learning how to care for patients so more people can live through it,” he said. “Getting to people early before they are so sick that they can’t be treated will not only improve survival rates but also prevent the virus from spreading.”

Dan formed friendships from a distance while there. “It’s this very strange juxtaposition where on one hand you are always conscious of not touching people, of not getting too close in a crowd, of constantly sanitizing your hands—and on the other hand you’re living very happy, collegial lives,” he said.

By the time he left, his team of local health workers was prepared to contain clusters of Ebola cases—a job that relies on community cooperation.

“I recently heard from the CDC staffer who replaced me that the team discovered 30 unreported Ebola cases in a single village,” Dan said. “The health official in the village thought Ebola was witchcraft and intentionally kept their outbreak a secret.”

Kim Lindblade and her team were dropped off in a football field near Geleyansiesu, Liberia, by a U.S. military helicopter. The remote village had a number of Ebola-related deaths.

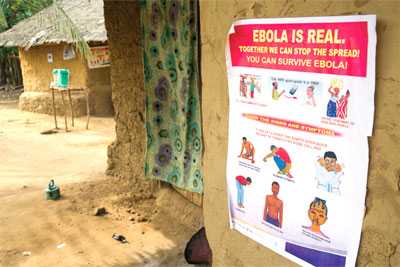

An "Ebola is Real" campaign poster in a Liberian village.

Kim Lindblade, a CDC epidemiologist, deployed to Liberia to investigate possible Ebola outbreaks in hard-to-reach places. If she saw cases of Ebola, her team would quickly start active case finding and contact tracing to limit spread of the disease.

“Earlier in the epidemic, most Ebola cases were in the densely populated city of Monrovia, but we found as it continued patients would leave and go back to their rural homes, causing outbreaks that were far from Ebola treatment units (ETUs),” Kim said.

CDC worked with ministry of health colleagues to isolate patients with cases of Ebola and arrange their safe transport to the nearest ETU and then track down their contacts.

“Over time, we started hearing about rural outbreaks faster. At the beginning, it could take weeks to hear about the first case, but by the time I left in late December, we were hearing about them within the first few days of illness. This led to outbreaks being resolved quicker, in less than half the time,” she said.

Kim recalls a report of two very sick people who had driven from Monrovia in a car with a patient suspected to have Ebola. When they arrived at the patient’s home, Kim and her team found more than 20 people living in the house.

“It was late in the evening and we had to scramble to buy chlorine and buckets to help them disinfect the home. We worked with the county health team to move the people to a quarantine facility the next day, and 21 days later every one of them left without becoming sick with Ebola,” she said.

- Page last reviewed: July 9, 2015

- Page last updated: July 9, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir