Wolbachia

Wolbachia is a genus of gram-negative bacteria that infects arthropod species, including a high proportion of insects, and also some nematodes.[4] It is one of the most common parasitic microbes and is possibly the most common reproductive parasite in the biosphere. Its interactions with its hosts are often complex, and in some cases have evolved to be mutualistic rather than parasitic. Some host species cannot reproduce, or even survive, without Wolbachia colonisation. One study concluded that more than 16% of neotropical insect species carry bacteria of this genus,[5] and as many as 25 to 70% of all insect species are estimated to be potential hosts.[6]

| Wolbachia | |

|---|---|

| |

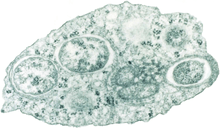

| Transmission electron micrograph of Wolbachia within an insect cell Credit:Public Library of Science / Scott O'Neill | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Wolbachia Hertig & Wolbach 1924 |

| Species[1] | |

History

The genus was first identified in 1924 by Marshall Hertig and Simeon Burt Wolbach in the common house mosquito. Hertig formally described the species in 1936 as Wolbachia pipientis.[7] Research on Wolbachia intensified after 1971, when Janice Yen and A. Ralph Barr of UCLA discovered that Culex mosquito eggs were killed by a cytoplasmic incompatibility when the sperm of Wolbachia-infected males fertilized infection-free eggs.[8][9] The genus Wolbachia is of considerable interest today due to its ubiquitous distribution, its many different evolutionary interactions, and its potential use as a biocontrol agent.

Method of sexual differentiation in hosts

These bacteria can infect many different types of organs, but are most notable for the infections of the testes and ovaries of their hosts. Wolbachia species are ubiquitous in mature eggs, but not mature sperm. Only infected females, therefore, pass the infection on to their offspring. Wolbachia bacteria maximize their spread by significantly altering the reproductive capabilities of their hosts, with four different phenotypes:

- Male killing occurs when infected males die during larval development, which increases the rate of born, infected, females.[10]

- Feminization results in infected males that develop as females or infertile pseudofemales. This is especially prevalent in Lepidoptera species such as the adzuki bean borer (Ostrinia scapulalis).[11]

- Parthenogenesis is reproduction of infected females without males. Some scientists have suggested that parthenogenesis may always be attributable to the effects of Wolbachia.[12] An example of parthenogenesis induced by presence of Wolbachia are some species within the Trichogramma wasp genus,[13] which have evolved to procreate without males due to the presence of Wolbachia. Males are rare in this genus of wasp, possibly because many have been killed by that same strain of Wolbachia.[14]

- Cytoplasmic incompatibility is the inability of Wolbachia-infected males to successfully reproduce with uninfected females or females infected with another Wolbachia strain. This reduces the reproductive success of those uninfected females and therefore promotes the infecting strain. In the cytoplasmic incompatibility mechanism, Wolbachia interferes with the parental chromosomes during the first mitotic divisions to the extent that they can no longer divide in sync.[15]

Effects of sexual differentiation in hosts

Several host species, such as those within the genus Trichogramma, are so dependent on sexual differentiation of Wolbachia that they are unable to reproduce effectively without the bacteria in their bodies, and some might even be unable to survive uninfected.[16]

One study on infected woodlice showed the broods of infected organisms had a higher proportion of females than their uninfected counterparts.[17]

Wolbachia, especially Wolbachia-caused cytoplasmic incompatibility, may be important in promoting speciation.[18][19][20] Wolbachia strains that distort the sex ratio may alter their host's pattern of sexual selection in nature,[21][22] and also engender strong selection to prevent their action, leading to some of the fastest examples of natural selection in natural populations.[23]

The male killing and feminization effects of Wolbachia infections can also lead to speciation in their hosts. For example, populations of the pill woodlouse, Armadillidium vulgare which are exposed to the feminizing effects of Wolbachia, have been known to lose their female-determining chromosome.[24] In these cases, only the presence of Wolbachia can cause an individual to develop into a female.[24] Cryptic species of ground wētā (Hemiandrus maculifrons complex) are host to different lineages of Wolbachia which might explain their speciation without ecological or geographical separation.[25][26]

Fitness advantages by Wolbachia infections

Wolbachia has been linked to viral resistance in Drosophila melanogaster, Drosophila simulans, and mosquito species. Flies infected with the bacteria are more resistant to RNA viruses such as Drosophila C virus, norovirus, flock house virus, cricket paralysis virus, chikungunya virus, and West Nile virus.[27][28][29]

In the common house mosquito, higher levels of Wolbachia were correlated with more insecticide resistance.[30]

In leafminers of the species Phyllonorycter blancardella, Wolbachia bacteria help their hosts produce green islands on yellowing tree leaves, that is, small areas of leaf remaining fresh, allowing the hosts to continue feeding while growing to their adult forms. Larvae treated with tetracycline, which kills Wolbachia, lose this ability and subsequently only 13% emerge successfully as adult moths.[31]

Muscidifurax uniraptor, a parasitoid wasp, also benefits from hosting Wolbachia bacteria.[32]

In the parasitic filarial nematode species responsible for elephantiasis, such as Brugia malayi and Wuchereria bancrofti, Wolbachia has become an obligate endosymbiont and provides the host with chemicals necessary to its reproduction and survival.[33] Elimination of the Wolbachia symbionts through antibiotic treatment therefore prevents reproduction of the nematode, and eventually results in its premature death.

Some Wolbachia species that infect arthropods also provide some metabolic provisioning to their hosts. In Drosophila melanogaster, Wolbachia is found to mediate iron metabolism under nutritional stress[34] and in Cimex lectularius, Wolbachia strain cCle helps the host to synthesize B vitamins.[35]

Wolbachia is also found to provide the host with a benefit of increasing fecundity. Wolbachia strains captured from 1988 in southern California still induce a fecundity deficit, but nowadays the fecundity deficit is replaced with a fecundity advantage such that infected Drosophila simulans produces more offspring than the uninfected ones.[36]

Genomics

The first Wolbachia genome to be determined was that of one that infects D. melanogaster fruit flies.[37] This genome was sequenced at The Institute for Genomic Research in a collaboration between Jonathan Eisen and Scott O'Neill. The second Wolbachia genome to be determined was one that infects Brugia malayi nematodes.[38] Genome sequencing projects for several other Wolbachia strains are in progress. A nearly complete copy of the Wolbachia genome sequence was found within the genome sequence of the fruit fly Drosophila ananassae and large segments were found in seven other Drosophila species.[39]

In an application of DNA barcoding to the identification of species of Protocalliphora flies, several distinct morphospecies had identical cytochrome c oxidase I gene sequences, most likely through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) by Wolbachia species as they jump across host species.[40] As a result, Wolbachia can cause misleading results in molecular cladistical analyses.[41] It is estimated that between 20 and 50 percent of insect species have evidence of HGT from Wolbachia—passing from microbes to animal (i.e. insects).[42]

Horizontal gene transfer

Wolbachia species also harbor a bacteriophage called bacteriophage WO or phage WO.[43] Comparative sequence analyses of bacteriophage WO offer some of the most compelling examples of large-scale horizontal gene transfer between Wolbachia coinfections in the same host.[44] It is the first bacteriophage implicated in frequent lateral transfer between the genomes of bacterial endosymbionts. Gene transfer by bacteriophages could drive significant evolutionary change in the genomes of intracellular bacteria that were previously considered highly stable or prone to loss of genes over time.[44]

Small RNA

The small non-coding RNAs WsnRNA-46 and WsnRNA-59 in Wolbachia were detected in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and Drosophila melanogaster. The small RNAs (sRNAs) may regulate bacterial and host genes.[45] Highly conserved intragenic region sRNA called ncrwmel02 was also identified in Wolbachia pipientis. It is expressed in four different strains in a regulated pattern that differs according to the sex of the host and the tissue localisation. This suggested that the sRNA may play important roles in the biology of Wolbachia.[46]

Applications to human-related infections

Wolbachia causing disease

Outside of insects, Wolbachia infects a variety of isopod species, spiders, mites, and many species of filarial nematodes (a type of parasitic worm), including those causing onchocerciasis (river blindness) and elephantiasis in humans, as well as heartworms in dogs. Not only are these disease-causing filarial worms infected with Wolbachia, but Wolbachia also seems to play an inordinate role in these diseases. A large part of the pathogenicity of filarial nematodes is due to host immune response toward their Wolbachia. Elimination of Wolbachia from filarial nematodes generally results in either death or sterility of the nematode.[47] Consequently, current strategies for control of filarial nematode diseases include elimination of their symbiotic Wolbachia via the simple doxycycline antibiotic, rather than directly killing the nematode with far more toxic antinematode medications.[48]

Wolbachia used to prevent disease

Naturally existing strains of Wolbachia have been shown to be a route for vector control strategies because of their presence in arthropod populations, such as mosquitoes.[49][50] Due to the unique traits of Wolbachia that cause cytoplasmic incompatibility, some strains are useful to humans as a promoter of genetic drive within an insect population. Wolbachia-infected females are able to produce offspring with uninfected and infected males; however, uninfected females are only able to produce viable offspring with uninfected males. This gives infected females a reproductive advantage that is greater the higher the frequency of Wolbachia in the population. Computational models predict that introducing Wolbachia strains into natural populations will reduce pathogen transmission and reduce overall disease burden.[51] An example includes a life-shortening Wolbachia that can be used to control dengue virus and malaria by eliminating the older insects that contain more parasites. Promoting the survival and reproduction of younger insects lessens selection pressure for evolution of resistance.[52][53]

In addition, some Wolbachia strains are able to directly reduce viral replication inside the insect. For dengue they include wAllbB and wMelPop with Aedes aegypti, wMel with Aedes albopictus.[54] and Aedes aegypti.[55] A trial in an Australian city with 187,000 inhabitants plagued by dengue had no cases in four years, following introduction of mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. Earlier trials in much smaller areas had been carried out, but the effect in a larger area had not been tested. There did not appear to be any environmental ill-effects. The cost was A$15 per inhabitant, but it was hoped that it could be reduced to US$1 in poorer countries.[56]

Wolbachia has also been identified to inhibit replication of chikungunya virus (CHIKV) in A. aegypti. The Wmel strain of Wolbachia pipientis significantly reduced infection and dissemination rates of CHIKV in mosquitoes, compared to Wolbachia uninfected controls and the same phenomenon was observed in yellow fever virus infection converting this bacterium in an excellent promise for YFV and CHIKV suppression.[57]

Wolbachia also inhibits the secretion of West Nile virus (WNV) in cell line Aag2 derived from A. aegypti cells. The mechanism is somewhat novel, as the bacteria actually enhances the production of viral genomic RNA in the cell line Wolbachia. Also, the antiviral effect in intrathoracically infected mosquitoes depends on the strain of Wolbachia, and the replication of the virus in orally fed mosquitoes was completely inhibited in wMelPop strain of Wolbachia.[58]

Wolbachia infection can also increase mosquito resistance to malaria, as shown in Anopheles stephensi where the wAlbB strain of Wolbachia hindered the lifecycle of Plasmodium falciparum.[59]

Wolbachia may induce reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of the Toll (gene family) pathway, which is essential for activation of antimicrobial peptides, defensins, and cecropins that help to inhibit virus proliferation.[60] Conversely, certain strains actually dampen the pathway, leading to higher replication of viruses. One example is with strain wAlbB in Culex tarsalis, where infected mosquitoes actually carried the west nile virus (WNV) more frequently. This is because wAlbB inhibits REL1, an activator of the antiviral Toll immune pathway. As a result, careful studies of the Wolbachia strain and ecological consequences must be done before releasing artificially-infected mosquitoes in the environment.[61]

Deployments

In 2016 it was proposed to combat the spread of the Zika virus by breeding and releasing mosquitoes that have intentionally been infected with an appropriate strain of Wolbachia.[62] A contemporary study has shown that Wolbachia has the ability to block the spread of Zika virus in mosquitoes in Brazil.[63]

In October 2016, it was announced that US$18 million in funding was being allocated for the use of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes to fight Zika and dengue viruses. Deployment is slated for early 2017 in Colombia and Brazil.[64]

In July 2017, Verily, the life sciences arm of Google’s parent company Alphabet Inc., announced a plan to release about 20 million Wolbachia-infected aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Fresno, California, in an attempt to combat the Zika virus. [65][66] Singapore's National Environment Agency has teamed up with Verily to come up with an advanced, more efficient way to release male Wolbachia mosquitoes for Phase 2 of its study to suppress the urban Aedes aegypti mosquito population and fight dengue.[67]

In November 3, 2017, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registered Mosquito Mate, Inc. to release Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in 20 US states and the District of Columbia.[68]

Effect on the sex-differentiation enzyme aromatase

The enzyme aromatase is found to mediate sex-change in many species of fish. Wolbachia can affect the activity of aromatase in developing fish embryos.[69]

See also

- Intragenomic conflict

- Quorum sensing

References

- Most Wolbachia species cannot be cultured outside of their eukaryotic host and so have not been given formal Latin names.

- Arguing that W. melophagi should be transferred to the genus Bartonella

- Dumler JS, Barbet AF, Bekker CP, et al. (November 2001). "Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and 'HGE agent' as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51 (Pt 6): 2145–65. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-6-2145. PMID 11760958.

- Lo N, Paraskevopoulos C, Bourtzis K, et al. (March 2007). "Taxonomic status of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia pipientis". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 (Pt 3): 654–7. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.64515-0. PMID 17329802.

- Arguing that W. persica should be transferred to the genus Francisella

- Forsman M, Sandström G, Sjöstedt A (January 1994). "Analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of Francisella strains and utilization for determination of the phylogeny of the genus and for identification of strains by PCR". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44 (1): 38–46. doi:10.1099/00207713-44-1-38. PMID 8123561.

- Noda H, Munderloh UG, Kurtti TJ (October 1997). "Endosymbionts of ticks and their relationship to Wolbachia spp. and tick-borne pathogens of humans and animals". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 (10): 3926–32. PMC 168704. PMID 9327557.

- Niebylski ML, Peacock MG, Fischer ER, Porcella SF, Schwan TG (October 1997). "Characterization of an endosymbiont infecting wood ticks, Dermacentor andersoni, as a member of the genus Francisella". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 (10): 3933–40. PMC 168705. PMID 9327558.

- Taylor, M.J. (2018). "Microbe Profile: Wolbachia: a sex selector, a viral protector and a target to treat filarial nematodes" (PDF). Microbiology. 164 (11): 1345–1347. doi:10.1099/mic.0.000724. PMID 30311871.

- Werren, J.H.; Guo, L; Windsor, D. W. (1995). "Distribution of Wolbachia among neotropical arthropods". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 262 (1364): 197–204. Bibcode:1995RSPSB.262..197W. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0196.

- Kozek, Wieslaw J.; Rao, Ramakrishna U. (2007). The Discovery of Wolbachia in Arthropods and Nematodes – A Historical Perspective. Issues in Infectious Diseases. 5. pp. 1–14. doi:10.1159/000104228. ISBN 978-3-8055-8180-6.

- Hertig, Marshall; Wolbach, S. Burt (1924). "Studies on Rickettsia-Like Micro-Organisms in Insects". Journal of Medical Research. 44 (3): 329–74. PMC 2041761. PMID 19972605.

- Yen JH; Barr AR (1971). "New hypothesis of the cause of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Culex pipiens". Nature. 232 (5313): 657–8. Bibcode:1971Natur.232..657Y. doi:10.1038/232657a0. PMID 4937405.

- Bourtzis, Kostas; Miller, Thomas A., eds. (2003). "14: Insect pest control using Wolbachia and/or radiation". Insect Symbiosis. p. 230. ISBN 9780849341946.

- Hurst G., Jiggins F. M., Graf von Der Schulenburg J. H., Bertrand D., et al. (1999). "Male killing Wolbachia in two species of insects". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 266 (1420): 735–740. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0698. PMC 1689827.

- Fujii, Y.; Kageyama, D.; Hoshizaki, S.; Ishikawa, H.; Sasaki, T. (2001-04-22). "Transfection of Wolbachia in Lepidoptera: the feminizer of the adzuki bean borer Ostrinia scapulalis causes male killing in the Mediterranean flour moth Ephestia kuehniella". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 268 (1469): 855–859. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1593. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1088680. PMID 11345332.

- Tortora, Gerard J.; Funke, Berdell R.; Case, Cristine L. (2007). Microbiology: an introduction. Pearson Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-4790-6.

- Knight J (5 July 2001). "Meet the Herod Bug". Nature. 412 (6842): 12–14. doi:10.1038/35083744. PMID 11452274.

- Murray, Todd. "Garden Friends & Foes: Trichogramma Wasps". Weeder's Digest. Washington State University Whatcom County Extension. Archived from the original on 2009-06-21. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- Breeuwer, JAJ; Werren, JH (1990). "Microorganisms associated with chromosome destruction and reproductive isolation between two insect species" (PDF). Nature. 346 (6284): 558–560. Bibcode:1990Natur.346..558B. doi:10.1038/346558a0. PMID 2377229.

- Werren, John H. (February 2003). "Invasion of the Gender Benders: by manipulating sex and reproduction in their hosts, many parasites improve their own odds of survival and may shape the evolution of sex itself". Natural History. 112 (1): 58. ISSN 0028-0712. OCLC 1759475.

- Rigaud, Thierry; Moreau, Jérôme; Juchault, Pierre (October 1999). "Wolbachia infection in the terrestrial isopod Oniscus asellus: sex ratio distortion and effect on fecundity". Heredity. 83 (4): 469–475. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6885990. PMID 10583549. However, the broods also often consisted of fewer eggs than the broods of the uninfected Oniscus asellus.

- Bordenstein, Seth R.; Patrick, O'Hara; Werren, John H. (2001). "Wolbachia-induced incompatibility precedes other hybrid incompatibilities in Nasonia". Nature. 409 (6821): 675–7. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..707B. doi:10.1038/35055543. PMID 11217858.

- Zimmer, Carl (2001). "Wolbachia: A Tale of Sex and Survival". Science. 292 (5519): 1093–5. doi:10.1126/science.292.5519.1093. PMID 11352061.

- Telschow, Arndt; Flor, Matthias; Kobayashi, Yutaka; Hammerstein, Peter; Werren, John H. (2007). Rees, Mark (ed.). "Wolbachia-Induced Unidirectional Cytoplasmic Incompatibility and Speciation: Mainland-Island Model". PLOS One. 2 (1): e701. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..701T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000701. PMC 1934337. PMID 17684548.

- Charlat S., Reuter M., Dyson E.A., Hornett E.A., Duplouy A.M.R., Davies N., Roderick G., Wedell N., Hurst G.D.D. (2006). "Male-killing bacteria trigger a cycle of increasing male fatigue and female promiscuity". Current Biology. 17 (3): 273–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.068. PMID 17276921.

- JIGGINS F. M.; Hurst, G. D. D.; Majerus, M. E. N. (2000). "Sex ratio distorting Wolbachia cause sex role reversal in their butterfly hosts". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 267 (1438): 69–73. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.0968. PMC 1690502. PMID 10670955.

- Charlat, S.; Hornett, E. A.; Fullard, J. H.; Davies, N.; Roderick, G. K.; Wedell, N.; Hurst, G. D. D. (2007). "Extraordinary Flux in Sex Ratio". Science. 317 (5835): 214. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..214C. doi:10.1126/science.1143369. PMID 17626876.

- Charlat, Sylvain (April 2003). "Evolutionary consequences of Wolbachia infections" (PDF). Trends in Genetics. 19 (4): 217–23. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00024-6. PMID 12683975. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Trewick, Steven A.; Wheeler, David; Morgan-Richards, Mary; Bridgeman, Benjamin (2018-04-25). "First detection of Wolbachia in the New Zealand biota". PLOS ONE. 13 (4): e0195517. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195517. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5918756. PMID 29694414.

- Taylor-Smith, B. L.; Trewick, S. A.; Morgan-Richards, M. (2016-10-01). "Three new ground wētā species and a redescription of Hemiandrus maculifrons". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 43 (4): 363–383. doi:10.1080/03014223.2016.1205109. ISSN 0301-4223.

- Teixeira, Luis; Ferreira, Alvaro; Ashburner, Michael (2008). Keller, Laurent (ed.). "The Bacterial Symbiont Wolbachia Induces Resistance to RNA Viral Infections in Drosophila melanogaster". PLOS Biology. 6 (12): e2. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002. PMC 2605931. PMID 19222304.

- Hedges, Lauren; Brownlie, Jeremy; O'Neill, Scott; Johnson, Karyn (2008). "Wolbachia and Virus Protection in Insects". Science. 322 (5902): 702. Bibcode:2008Sci...322..702H. doi:10.1126/science.1162418. PMID 18974344.

- Glaser, Robert L.; Meola, Mark A. (2010). "The Native Wolbachia Endosymbionts of Drosophila melanogaster and Culex quinquefasciatus Increase Host Resistance to West Nile Virus Infection". PLOS ONE. 5 (8): e11977. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511977G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011977. PMC 2916829. PMID 20700535.

- Berticat C, Rousset F, Raymond M, Berthomieu A, Weill M (July 2002). "High Wolbachia density in insecticide-resistant mosquitoes". Proc. Biol. Sci. 269 (1498): 1413–6. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2022. PMC 1691032. PMID 12079666.

- Kaiser W, Huguet E, Casas J, Commin C, Giron D (August 2010). "Plant green-island phenotype induced by leaf-miners is mediated by bacterial symbionts". Proc. Biol. Sci. 277 (1692): 2311–9. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0214. PMC 2894905. PMID 20356892.

- Zchori-Fein, Einat (2000). "Wolbachia Density and Host Fitness Components in Muscidifurax uniraptor (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae)" (PDF). Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 75 (4): 267–272. doi:10.1006/jipa.2000.4927. PMID 10843833. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- Foster, Jeremy; Ganatra, Mehul; Kamal, Ibrahim; Ware, Jennifer; Makarova, Kira; Ivanova, Natalia; Bhattacharyya, Anamitra; Kapatral, Vinayak; et al. (2005). "The Wolbachia Genome of Brugia malayi: Endosymbiont Evolution within a Human Pathogenic Nematode". PLOS Biology. 3 (4): e121. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030121. PMC 1069646. PMID 15780005.

- Brownlie, J.C.; Cass, B. N.; Riegler, M. (2009). "Evidence for metabolic provisioning by a common invertebrate endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, during periods of nutritional stress". PLOS Pathogens. 5 (4): e1000368. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000368. PMC 2657209. PMID 19343208.

- Nikoh, N.; Hosokawa, T.; Moriyama, M. (2014). "Evolutionary origin of insect- Wolbachia nutritional mutualism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (28): 10257–10262. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110257N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1409284111. PMC 4104916. PMID 24982177.

- Weeks, A.R.; Turelli, M.; Harcombe, W.R. (2007). "From parasite to mutualist: rapid evolution of Wolbachia in natural populations of Drosophila". PLOS Biology. 5 (5): e114. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050114. PMC 1852586. PMID 17439303.

- Wu M, Sun LV, Vamathevan J, et al. (2004). "Phylogenomics of the Reproductive Parasite Wolbachia pipientis wMel: A Streamlined Genome Overrun by Mobile Genetic Elements". PLOS Biology. 2 (3): e69. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020069. PMC 368164. PMID 15024419.

- Foster J, Ganatra M, Kamal I, et al. (2005). "The Wolbachia Genome of Brugia malayi: Endosymbiont Evolution within a Human Pathogenic Nematode". PLOS Biology. 3 (4): e121. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030121. PMC 1069646. PMID 15780005.

- Dunning Hotopp, J.C, Clark ME, Oliveira DC, Foster JM, Fischer P, Torres MC, Giebel JD, Kumar N, Ishmael N, Wang S, Ingram J, Nene RV, Shepard J, Tomkins J, Richards S, Spiro DJ, Ghedin E, Slatko BE, Tettelin H, Werren J.H.; Clark; Oliveira; Foster; Fischer; Torres; Giebel; Kumar; Ishmael; Wang; Ingram; Nene; Shepard; Tomkins; Richards; Spiro; Ghedin; Slatko; Tettelin; Werren (2007). "Widespread Lateral Gene Transfer from Intracellular Bacteria to Multicellular Eukaryotes". Science. 317 (5845): 1753–6. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1753H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.1320. doi:10.1126/science.1142490. PMID 17761848.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Whitworth, TL; Dawson, RD; Magalon, H; Baudry, E (2007). "DNA barcoding cannot reliably identify species of the blowfly genus Protocalliphora (Diptera: Calliphoridae)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 274 (1619): 1731–9. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0062. PMC 2493573. PMID 17472911.

- Johnstone, RA; Hurst, GDD (1996). "Maternally inherited male-killing microorganisms may confound interpretation of mitochondrial DNA variability". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 58 (4): 453–470. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1996.tb01446.x.

- Ed, Yong (2016-08-09). I contain multitudes : the microbes within us and a grander view of life (First U.S. ed.). New York, NY. p. 197. ISBN 9780062368591. OCLC 925497449.

- Masui S, Kamoda S, Sasaki T, Ishikawa H (2000). "Distribution and evolution of bacteriophage WO in Wolbachia, the endosymbiont causing sexual alterations in arthropods". J Mol Evol. 51 (5): 491–497. Bibcode:2000JMolE..51..491M. doi:10.1007/s002390010112. PMID 11080372.

- Kent, Bethany N.; Salichos, Leonidas; Gibbons, John G.; Rokas, Antonis; Newton, Irene L.; Clark, Michael E.; Bordenstein, Seth R. (2011). "Complete Bacteriophage Transfer in a Bacterial Endosymbiont (Wolbachia) Determined by Targeted Genome Capture". Genome Biology and Evolution. 3: 209–218. doi:10.1093/gbe/evr007. PMC 3068000. PMID 21292630.

- Mayoral, Jaime G.; Hussain, Mazhar; Joubert, D. Albert; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, Iñaki; O'Neill, Scott L.; Asgari, Sassan (2014-12-30). "Wolbachia small noncoding RNAs and their role in cross-kingdom communications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (52): 18721–18726. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11118721M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420131112. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 4284532. PMID 25512495.

- Woolfit, Megan; Algama, Manjula; Keith, Jonathan M.; McGraw, Elizabeth A.; Popovici, Jean (2015-01-01). "Discovery of putative small non-coding RNAs from the obligate intracellular bacterium Wolbachia pipientis". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0118595. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018595W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118595. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4349823. PMID 25739023.

- Hoerauf A, Mand S, Fischer K, et al. (2003). "Doxycycline as a novel strategy against bancroftian filariasis-depletion of Wolbachia endosymbionts from Wuchereria bancrofti and stop of microfilaria production". Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 192 (4): 211–6. doi:10.1007/s00430-002-0174-6. PMID 12684759.

- Taylor, MJ; Makunde, WH; McGarry, HF; Turner, JD; Mand, S; Hoerauf, A (2005). "Macrofilaricidal activity after doxycycline treatment of Wuchereria bancrofti: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 365 (9477): 2116–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66591-9. PMID 15964448.

- Xi, Z; Dean JL; Khoo C; Dobson SL. (2005). "Generation of a novel Wolbachia infection in Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger mosquito) via embryonic microinjection". Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 35 (8): 903–10. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.03.015. PMC 1410910. PMID 15944085.

- Moreira, LA; Iturbe-ormaetxe I; Jeffery JA; et al. (2009). "A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium". Cell. 139 (7): 1268–78. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. PMID 20064373.

- Hancock, PA; Sinkins SP; Godfray HC. (2011). "Strategies for introducing Wolbachia to reduce transmission of mosquito-borne diseases". PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5 (4): e1024. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001024. PMC 3082501. PMID 21541357.

- Mcmeniman, CJ; Lane RV; Cass BN; et al. (2009). "Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti". Science. 323 (5910): 141–4. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..141M. doi:10.1126/science.1165326. PMID 19119237.

- "'Bug' could combat dengue fever". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2 January 2009.

- Blagrove, MS; Arias-goeta C; Failloux AB; Sinkins SP. (2012). "Wolbachia strain wMel induces cytoplasmic incompatibility and blocks dengue transmission in Aedes albopictus". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109 (1): 255–60. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109..255B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112021108. PMC 3252941. PMID 22123944.

- Hoffmann, AA; Iturbe-Ormaetxe I; Callahan AG; Phillips BL. (2014). "Stability of the wMel Wolbachia Infection following invasion into Aedes aegypti populations". PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8 (9): e3115. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003115. PMC 4161343. PMID 25211492.

- Sarah Boseley (1 August 2018). "Dengue fever outbreak halted by release of special mosquitoes". The Guardian.

- van den Hurk, AF; Hall-Mendelin S; Pyke AT; Frentiu FD. (2012). "Impact of Wolbachia on infection with chikungunya and yellow fever viruses in the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti". PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6 (11): e1892. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001892. PMC 3486898. PMID 23133693.

- Hussain, M; Lu G; Torres S; Edmonds JH. (2013). "Effect of Wolbachia on replication of West Nile virus in a mosquito cell line and adult mosquitoes". J Virol. 87 (2): 851–858. doi:10.1128/JVI.01837-12. PMC 3554047. PMID 23115298.

- Bian, G; Joshi D; Dong Y; et al. (2013). "Wolbachia invades Anopheles stephensi populations and induces refractoriness to Plasmodium infection". Science. 340 (6133): 748–51. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..748B. doi:10.1126/science.1236192. PMID 23661760.

- Pan, X; Zhou G; Wu J; et al. (2012). "Wolbachia induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent activation of the Toll pathway to control dengue virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109 (1): E23–31. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E..23P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1116932108. PMC 3252928. PMID 22123956.

- Dodson, BL; Grant H; Oluwatobi P. (2014). "Wolbachia Enhances West Nile Virus (WNV) Infection in the Mosquito Culex tarsalis". PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8 (7): e2965. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002965. PMC 4091933. PMID 25010200.

- Jason Gale (4 February 2016). "The Best Weapon for Fighting Zika? More Mosquitoes". Bloomberg.com.

- Dutra, Heverton Leandro Carneiro; Rocha, Marcele Neves; Dias, Fernando Braga Stehling; Mansur, Simone Brutman; Caragata, Eric Pearce; Moreira, Luciano Andrade (2016). "Wolbachia Blocks Currently Circulating Zika Virus Isolates in Brazilian Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes". Cell Host & Microbe. 19 (6): 771–774. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.021. PMC 4906366. PMID 27156023.

- "Wolbachia efforts ramp up to fight Zika in Brazil, Colombia".

- Buhr, Sarah. "Google's life sciences unit is releasing 20 million bacteria-infected mosquitoes in Fresno". TechCrunch. Oath Inc. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Mullin, Emily. "Verily Robot Will Raise 20 Million Sterile Mosquitoes for Release in California". MIT Technology Review. MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- "NEA, Alphabet Inc's Verily team up to fight dengue with AI". Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- "EPA Registers the Wolbachia ZAP Strain in Live Male Asian Tiger Mosquitoes". Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- https://ourblueplanet.bbcearth.com/blog/?article=incredible-sex-changing-fish-from-blue-planet

Further reading

- Werren, J.H. (1997). "Biology of Wolbachia" (PDF). Annual Review of Entomology. 42: 587–609. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.587. PMID 15012323.

- Klasson L, Westberg J, Sapountzis P, Näslund K, Lutnaes Y, Darby AC, Veneti Z, Chen L, Braig HR, Garrett R, Bourtzis K, Andersson SG; Westberg; Sapountzis; Näslund; Lutnaes; Darby; Veneti; Chen; Braig; Garrett; Bourtzis; Andersson (23 March 2009). "The mosaic genome structure of the Wolbachia wRi strain infecting Drosophila simulans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (14): 5725–30. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5725K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810753106. PMC 2659715. PMID 19307581.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Virtual Museum of Bacteria

- Wolbachia research portal National Science Foundation

- "One Species' Genome Discovered Inside Another's—Bacterial to Animal Gene Transfers Now Shown to be Widespread, with Implications for Evolution and Control of Diseases and Pests". University of Rochester. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- "Wolbachia" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Howard Hughes Medical Institute High School Lab Series

- Images of Wolbachia