Waterborne diseases

Waterborne diseases are conditions caused by pathogenic micro-organisms that are transmitted in water. Disease can be spread while bathing, washing, drinking water, or by eating food exposed to contaminated water. While diarrhea and vomiting are the most commonly reported symptoms of waterborne illness, other symptoms can include skin, ear, respiratory, or eye problems.[1]

| Waterborne diseases | |

|---|---|

| |

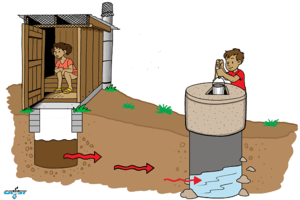

| Waterborne diseases can be spread via groundwater which is contaminated with fecal pathogens from pit latrines | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Various forms of waterborne diarrheal disease are the most prominent examples, and affect children in developing countries most dramatically. According to the World Health Organization, waterborne diseases account for an estimated 3.6% of the total DALY (disability- adjusted life year) global burden of disease, and cause about 1.5 million human deaths annually. The World Health Organization estimates that 58% of that burden, or 842,000 deaths per year, is attributable to a lack of safe drinking water supply, sanitation and hygiene (summarized as WASH).[2]

The term waterborne disease is reserved largely for infections that predominantly are transmitted through contact with or consumption of infected water. Trivially, many infections may be transmitted by microbes or parasites that accidentally, possibly as a result of exceptional circumstances, have entered the water, but the fact that there might be an occasional freak infection need not mean that it is useful to categorise the resulting disease as "waterborne". Nor is it common practice to refer to diseases such as malaria as "waterborne" just because mosquitoes have aquatic phases in their life cycles, or because treating the water they inhabit happens to be an effective strategy in control of the mosquitoes that are the vectors.

Microorganisms causing diseases that characteristically are waterborne prominently include protozoa and bacteria, many of which are intestinal parasites, or invade the tissues or circulatory system through walls of the digestive tract. Various other waterborne diseases are caused by viruses. (In spite of philosophical difficulties associated with defining viruses as "organisms", it is practical and convenient to regard them as microorganisms in this connection.)

Yet other important classes of water-borne diseases are caused by metazoan parasites. Typical examples include certain Nematoda, that is to say "roundworms". As an example of water-borne Nematode infections, one important waterborne nematodal disease is Dracunculiasis. It is acquired by swallowing water in which certain copepoda occur that act as vectors for the Nematoda. Anyone swallowing a copepod that happens to be infected with Nematode larvae in the genus Dracunculus, becomes liable to infection. The larvae cause guinea worm disease.[3]

Another class of waterborne metazoan pathogens are certain members of the Schistosomatidae, a family of blood flukes. They usually infect victims that make skin contact with the water.[3] Blood flukes are pathogens that cause Schistosomiasis of various forms, more or less seriously affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide.[4]

Long before modern studies had established the germ theory of disease, or any advanced understanding of the nature of water as a vehicle for transmitting disease, traditional beliefs had cautioned against the consumption of water, rather favouring processed beverages such as beer, wine and tea. For example, in the camel caravans that crossed Central Asia along the Silk Road, the explorer Owen Lattimore noted, "The reason we drank so much tea was because of the bad water. Water alone, unboiled, is never drunk. There is a superstition that it causes blisters on the feet."[5]

Socioeconomic impact

Waterborne diseases can have a significant impact on the economy, locally as well as internationally. People who are infected by a waterborne disease are usually confronted with related costs and not seldom with a huge financial burden. This is especially the case in less developed countries. The financial losses are mostly caused by e.g. costs for medical treatment and medication, costs for transport, special food, and by the loss of manpower. Many families must even sell their land to pay for treatment in a proper hospital. On average, a family spends about 10% of the monthly households income per person infected.[6]

Infections by type of pathogen

Protozoa

| Disease and Transmission | Microbial Agent | Sources of Agent in Water Supply | General Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthamoeba keratitis (cleaning of contact lenses with contaminated water) | Acanthamoeba spp. (A. castellanii and A. polyphaga) | widely-distributed free-living amoebae found in many types of aquatic environments, including surface water, tap water, swimming pools, and contact lens solutions | Eye pain, eye redness, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, sensation of something in the eye, and excessive tearing |

| Amoebiasis (hand-to-mouth) | Protozoan (Entamoeba histolytica) (Cyst-like appearance) | Sewage, non-treated drinking water, flies in water supply, saliva transfer(if the other person has the disease) | Abdominal discomfort, fatigue, weight loss, diarrhea, bloating, fever |

| Cryptosporidiosis (oral) | Protozoan (Cryptosporidium parvum) | Collects on water filters and membranes that cannot be disinfected, animal manure, seasonal runoff of water. | Flu-like symptoms, watery diarrhea, loss of appetite, substantial loss of weight, bloating, increased gas, nausea |

| Cyclosporiasis | Protozoan parasite (Cyclospora cayetanensis) | Sewage, non-treated drinking water | cramps, nausea, vomiting, muscle aches, fever, and fatigue |

| Giardiasis (fecal-oral) (hand-to-mouth) | Protozoan (Giardia lamblia) Most common intestinal parasite | Untreated water, poor disinfection, pipe breaks, leaks, groundwater contamination, campgrounds where humans and wildlife use same source of water. Beavers and muskrats create ponds that act as reservoirs for Giardia. | Diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, bloating, and flatulence |

| Microsporidiosis | Protozoan phylum (Microsporidia), but closely related to fungi | Encephalitozoon intestinalis has been detected in groundwater, the origin of drinking water[7] | Diarrhea and wasting in immunocompromised individuals. |

| Naegleriasis (primary amebic meningoencephalitis [PAM]) (nasal) | Protozoan (Naegleria fowleri) (Cyst-like appearance) | Watersports, non-chlorinated water | Headache, vomiting, confusion, loss of balance, light sensitivity, hallucinations, fatigue, weight loss, fever, and coma |

Bacteria

| Disease and Transmission | Microbial Agent | Sources of Agent in Water Supply | General Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botulism | Clostridium botulinum | Bacteria can enter an open wound from contaminated water sources. Can enter the gastrointestinal tract through consumption of contaminated drinking water or (more commonly) food | Dry mouth, blurred and/or double vision, difficulty swallowing, muscle weakness, difficulty breathing, slurred speech, vomiting and sometimes diarrhea. Death is usually caused by respiratory failure. |

| Campylobacteriosis | Most commonly caused by Campylobacter jejuni | Drinking water contaminated with feces | Produces dysentery-like symptoms along with a high fever. Usually lasts 2–10 days. |

| Cholera | Spread by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae | Drinking water contaminated with the bacterium | In severe forms it is known to be one of the most rapidly fatal illnesses known. Symptoms include very watery diarrhea, nausea, cramps, nosebleed, rapid pulse, vomiting, and hypovolemic shock (in severe cases), at which point death can occur in 12–18 hours. |

| E. coli Infection | Certain strains of Escherichia coli (commonly E. coli) | Water contaminated with the bacteria | Mostly diarrhea. Can cause death in immunocompromised individuals, the very young, and the elderly due to dehydration from prolonged illness. |

| M. marinum infection | Mycobacterium marinum | Naturally occurs in water, most cases from exposure in swimming pools or more frequently aquariums; rare infection since it mostly infects immunocompromised individuals | Symptoms include lesions typically located on the elbows, knees, and feet (from swimming pools) or lesions on the hands (aquariums). Lesions may be painless or painful. |

| Dysentery | Caused by a number of species in the genera Shigella and Salmonella with the most common being Shigella dysenteriae | Water contaminated with the bacterium | Frequent passage of feces with blood and/or mucus and in some cases vomiting of blood. |

| Legionellosis (two distinct forms: Legionnaires' disease and Pontiac fever) | Caused by bacteria belonging to genus Legionella (90% of cases caused by Legionella pneumophila) | Legionella is a very common organism that reproduces to high numbers in warm water;[9] but only causes severe disease when aerosolized.[10] | Pontiac fever produces milder symptoms resembling acute influenza without pneumonia. Legionnaires' disease has severe symptoms such as fever, chills, pneumonia (with cough that sometimes produces sputum), ataxia, anorexia, muscle aches, malaise and occasionally diarrhea and vomiting |

| Leptospirosis | Caused by bacterium of genus Leptospira | Water contaminated by the animal urine carrying the bacteria | Begins with flu-like symptoms then resolves. The second phase then occurs involving meningitis, liver damage (causes jaundice), and renal failure |

| Otitis Externa (swimmer's ear) | Caused by a number of bacterial and fungal species. | Swimming in water contaminated by the responsible pathogens | Ear canal swells, causing pain and tenderness to the touch |

| Salmonellosis | Caused by many bacteria of genus Salmonella | Drinking water contaminated with the bacteria. More common as a food borne illness. | Symptoms include diarrhea, fever, vomiting, and abdominal cramps |

| Typhoid fever | Salmonella typhi | Ingestion of water contaminated with feces of an infected person | Characterized by sustained fever up to 40 °C (104 °F), profuse sweating; diarrhea may occur. Symptoms progress to delirium, and the spleen and liver enlarge if untreated. In this case it can last up to four weeks and cause death. Some people with typhoid fever develop a rash called "rose spots", small red spots on the abdomen and chest. |

| Vibrio Illness | Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio alginolyticus, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Can enter wounds from contaminated water. Also acquired by drinking contaminated water or eating undercooked oysters. | Symptoms include abdominal tenderness, agitation, bloody stools, chills, confusion, difficulty paying attention (attention deficit), delirium, fluctuating mood, hallucination, nosebleeds, severe fatigue, slow, sluggish, lethargic feeling, weakness. |

Viruses

| Disease and Transmission | Viral Agent | Sources of Agent in Water Supply | General Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) | Coronavirus | Manifests itself in improperly treated water | Symptoms include fever, myalgia, lethargy, gastrointestinal symptoms, cough, and sore throat |

| Hepatitis A | Hepatitis A virus (HAV) | Can manifest itself in water (and food) | Symptoms are only acute (no chronic stage to the virus) and include Fatigue, fever, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, weight loss, itching, jaundice and depression. |

| Hepatitis E (fecal-oral) | Hepatitis E virus (HEV) | Enters water through the feces of infected individuals | Symptoms of acute hepatitis (liver disease), including fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, jaundice, dark urine, clay-colored stool, and joint pain |

| Acute gastrointestinal illness [AGI] (fecal-oral; spread by food, water, person-to-person, and fomites) | Norovirus | Enters water through the feces of infected individuals | Diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, stomach pain |

| Poliomyelitis (Polio) | Poliovirus | Enters water through the feces of infected individuals | 90-95% of patients show no symptoms, 4-8% have minor symptoms (comparatively) with delirium, headache, fever, and occasional seizures, and spastic paralysis, 1% have symptoms of non-paralytic aseptic meningitis. The rest have serious symptoms resulting in paralysis or death |

| Polyomavirus infection | Two of Polyomavirus: JC virus and BK virus | Very widespread, can manifest itself in water, ~80% of the population has antibodies to Polyomavirus | BK virus produces a mild respiratory infection and can infect the kidneys of immunosuppressed transplant patients. JC virus infects the respiratory system, kidneys or can cause progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in the brain (which is fatal). |

Algae

| Disease and Transmission | Microbial Agent | Sources of Agent in Water Supply | General Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desmodesmus infection | desmodesmus armatus | Naturally occurs in water. Can enter open wounds. | Similar to fungal infection. |

Parasitic worms

| Disease and Transmission | Agent | Sources of Agent in Water Supply | General Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dracunculiasis [Guinea worm disease] (ingestion of contaminated water) | Dracunculus medinensis | Female worm emerges from host skin and releases larvae in water | Slight fever, itchy rash, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, followed by formation of painful blister (typically on lower body parts) |

Surveillance

In the United States

The Waterborne Disease and Outbreak Surveillance System (WBDOSS) is the principal database used to identify the causative agents, deficiencies, water systems, and sources associated with waterborne disease and outbreaks in the United States.[16] Since 1971, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have maintained this surveillance system for collecting and reporting data on "waterborne disease and outbreaks associated with recreational water, drinking water, environmental, and undetermined exposures to water."[16][17] "Data from WBDOSS have supported EPA efforts to develop drinking water regulations and have provided guidance for CDC’s recreational water activities."[16][17]

WBDOSS relies on complete and accurate data from public health departments in individual states, territories, and other U.S. jurisdictions regarding waterborne disease and outbreak activity.[16] In 2009, reporting to the WBDOSS transitioned from a paper form to the electronic National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS).[16] Annual or biennial surveillance reports of the data collected by the WBDOSS have been published in CDC reports from 1971 to 1984; since 1985, surveillance data have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR).[16]

See also

References

- Guidelines for drinking-water quality. World Health Organization (Fourth edition incorporating the first addendum ed.). Geneva. ISBN 9789241549950. OCLC 975491910.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Burden of disease and cost-effectiveness estimates". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- Janovy J, Schmidt GD, Roberts LS (1996). Gerald D. Schmidt & Larry S. Roberts' Foundations of parasitology. Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown. ISBN 978-0-697-26071-0.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ) (2011). "Chapter 3". In Brunette GW (ed.). CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012. The Yellow Book. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976901-8.

- Lattimore (1928). "The caravan routes of inner Asia". The Geographical Journal. 72 (6): 500. doi:10.2307/1783443. JSTOR 1783443. quoted in Wood F (2002). The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. p. 19.

- Schnabel B. "Drastic consequences of diarrhoeal disease". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- Nwachcuku N, Gerba CP (June 2004). "Emerging waterborne pathogens: can we kill them all?" (PDF). Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 15 (3): 175–80. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2004.04.010. PMID 15193323. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-03-07.

- Baldursson S, Karanis P (December 2011). "Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: review of worldwide outbreaks - an update 2004-2010". Water Research. 45 (20): 6603–14. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2011.10.013. PMID 22048017.

- "Legionnaires' Disease eTool: Facts and FAQs". www.osha.gov. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Legionella - Causes and Transmission - Legionnaires - CDC". www.cdc.gov. 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Dziuban EJ, Liang JL, Craun GF, Hill V, Yu PA, Painter J, Moore MR, Calderon RL, Roy SL, Beach MJ (December 2006). "Surveillance for waterborne disease and outbreaks associated with recreational water--United States, 2003-2004". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. 55 (12): 1–30. PMID 17183230. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017.

- Petrini B (October 2006). "Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 25 (10): 609–13. doi:10.1007/s10096-006-0201-4. PMID 17047903.

- Nwachuku N, Gerba CP, Oswald A, Mashadi FD (September 2005). "Comparative inactivation of adenovirus serotypes by UV light disinfection" (PDF). Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 71 (9): 5633–6. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.9.5633-5636.2005. PMC 1214670. PMID 16151167. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-26.

- Gall AM, Mariñas BJ, Lu Y, Shisler JL (June 2015). "Waterborne Viruses: A Barrier to Safe Drinking Water". PLoS Pathogens. 11 (6): e1004867. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004867. PMC 4482390. PMID 26110535.

- Westblade, Lars F.; Ranganath, Sangeetha; Dunne, William Michael; Burnham, Carey-Ann D.; Fader, Robert; Ford, Bradley A. (March 5, 2015). "Infection with a Chlorophyllic Eukaryote after a Traumatic Freshwater Injury". New England Journal of Medicine. The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (10): 982–984. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1401816. PMID 25738686.

- "Waterborne Disease & Outbreak Surveillance Reporting | Water-related Topics | Healthy Water | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2017-10-16. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- Craun, Gunther F. (2004). Methods for the investigation and prevention of waterborne disease outbreaks; EPA/600/1-90/005A. Health Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. OCLC 41657130.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|

- Water-related Diseases, Contaminants, and Injuries Listing of water-related diseases, contaminants and injuries with alphabetical index, listing by type of disease (bacterial, parasitic, etc.) and listing by symptoms caused (diarrhea, skin rash, and many more ) including links to other resources (CDC's Healthy Water site)

- World Health Organization (WHO) "Water-Related Diseases"