Vestibular rehabilitation

Vestibular rehabilitation (VR), also known as vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT), is a specialized form of physical therapy used to treat vestibular disorders or symptoms, characterized by dizziness, vertigo, and trouble with balance, posture, and vision. These primary symptoms can result in secondary symptoms such as nausea, fatigue, and lack of concentration. All symptoms of vestibular dysfunction can significantly decrease quality of life, introducing mental-emotional issues such as anxiety and depression, and greatly impair an individual, causing them to become more sedentary. Decreased mobility results in weaker muscles, less flexible joints, and worsened stamina, as well as decreased social and occupational activity. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy can be used in conjunction with cognitive behavioral therapy in order to reduce anxiety and depression resulting from an individual's change in lifestyle.[1][2]

Vestibular disorders

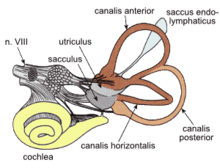

The term "vestibular" refers to the inner ear system with its fluid-filled canals that allow for balance and spatial orientation. Some common vestibular disorders include vestibular neuritis, Ménière's disease, and nerve compression. Vestibular dysfunction can exist unilaterally, affecting only one side of the body, or bilaterally, affecting both sides.[2]

The most commonly vestibular disorder is called Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). The BPPV is characterized by temporary dizziness feeling associated with blurred vision in relation to certain head positions. BPPV may affects anterior, posterior or horizontal vestibular canals. Posterior canal was reported in the literature as the most commonly affected canal, 80% of the patients diagnosed with BPPV. Several positional tests such as Hall-bike dix test, supine roll test, and head shaking nystagmus test may indicate which canal is affected by BPPV.[3]

Vestibular damage is often irreparable and symptoms are persistent. Although the body naturally compensates for vestibular dysfunction (as it does for the dysfunction or deficiency of any sense), vestibular rehabilitation furthers the compensation process to decrease both primary and secondary symptoms. In cases of chronic vestibular dysfunction, medication in the form of vestibular suppressants does not allow the nervous system to undergo compensation. Thus, long-term medication is not a viable option for individuals with chronic vestibular dysfunction. Because of this, vestibular rehabilitation therapy is a better alternative for long-term vestibular dysfunction. However, some medications, such as anticholinergics, antihistamines, and benzodiazepines, are useful in acute cases (of 5 days or less) for reducing nausea and other secondary symptoms.[4]

Diagnostic tests

Because the methods of vestibular rehabilitation therapy differ for different disorders, the form of vestibular dysfunction, ability level, and history of symptoms, each patient must be carefully assessed in order to diagnose vestibular dysfunction and to choose the correct exercises for treatment. In some cases, vestibular rehabilitation may not be the appropriate treatment at all. Vestibular disorders can be diagnosed using several different kinds of assessments, some of which include examination of an individual's ability to maintain posture, balance, and head position. Some diagnostic tests are more easily performed in a clinical setting than others but relay less specific information to the tester, and vice versa. A proper history of symptoms should include what those symptoms are, how often they occur, and under what circumstances, including whether the symptoms are triggered or spontaneous.[2] Other conditions that can be treated with vestibular rehabilitation therapy are symptoms of concussions[5] and dizziness in patients with multiple sclerosis.[6] Magnetic resonance imaging techniques can be used as diagnostic tools to determine the presence of issues that can be treated with vestibular rehabilitation, regardless of whether they are vestibular in nature.

Caloric reflex test

The caloric reflex test is designed to test the function of the vestibular system and can determine the cause of vestibular symptoms. The reflex test consists of pouring water into the external auditory canal of a patient and observing nystagmus, or involuntary eye movement. With normal vestibular function, the temperature of the water has an effect on the direction of eye movement. In individuals with peripheral unilateral vestibular hypofunction, nystagmus is absent.[2]

Rotational chair testing

This test is used to test bilateral vestibular hypofunction and the degree of central nervous system (CNS) compensation that results. Movement of fluid within the inner ear, known as endolymph, is responsible for the relationship between eye movement and head velocity. The test consists of seating a patient in a rotating chair, rotating the chair to specific velocity, and observing eye movement. In individuals with normal vestibular function, the velocity of eye movement should be equal and opposite that of head movement. Lower rotational velocities are used to assess extent of CNS compensation.[2]

Visual perception testing

Visual perception testing can assess a patient's ability to determine vertically- and horizontally-oriented objects, but with a limited degree of specificity. When asked to align a bar to horizontal or vertical, an individual with normal vestibular function can align the bar within 2.5 degrees of horizontal or vertical. An inability to do so indicates vestibular dysfunction. In some cases, the direction of tilt away from the desired orientation is on the same side as the dysfunction, while in some cases the opposite is true.[2]

Posturography

Using various technologies to assess a person's ability to maintain posture and balance, different patterns of posturography can be determined. Once a pattern is determined, the modalities and inputs that the person relies on to maintain balance can be inferred. Knowing what systems and structures influence a person's stance can suggest different areas of dysfunction and preference.[2]

Non-vestibular dizziness

In some cases, the results of vestibular tests are normal, yet the patient experiences vestibular symptoms, especially balance issues and dangerous falls. Some diagnoses that result in non-vestibular dizziness are concussions, Parkinson's disease, cerebellar ataxia, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, leukoaraiosis, progressive supranuclear palsy, and large-fiber peripheral neuropathy. There are also several disorders known as chronic situation-related dizziness disorders. For example, phobic postural vertigo (PPV) occurs when an individual with obsessive-compulsive characteristics experiences a sense of imbalance, despite the absence of balance issues. Chronic subjective dizziness (CSD) is a similar condition characterized by persistent vertigo, hypersensitivity to motion stimuli, and difficulty with precise visual tasks. Both phobic postural vertigo and chronic subjective dizziness may be treated with vestibular rehabilitation therapy or other therapeutic methods such as cognitive behavioral therapy and conditioning.[2]

Rehabilitation exercises

Vestibular rehabilitation is specific to the dysfunction that a patient experiences. Some treatment methods seek to eliminate the cause of vestibular dysfunction, while others allow the brain to compensate for dysfunction without targeting the source. The former goal is for treating benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, while the latter treats vestibular hypofunction, which cannot be cured. The treatment process should begin as early as possible, to decrease fall risk. The patient should start slowly, gradually increasing the intensity and duration of exercises, and be accompanied by an accessible and reassuring therapist, as discomfort and negative emotional states can negatively affect treatment.[2]

Treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

Treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BBPV) depends on the canals involved (horizontal or vertical) and which form of BBPV the patient is experiencing (canalithiasis versus cupulolithiasis). Canalithiasis is characterized by a dislodged otolith particle, called otoconia, that floats in the fluid in one of the three vestibular canals and cause the feeling of dizziness with vision disturbances. On the other hand, cupulolithiasis is another form of BPPV caused by an attachment of otolith particle in the cupula (the base of semicircular canal) of the involved canal.[7]

Canalith repositioning treatments

Canalith repositioning treatments (CRT) aim to move debris in the inner ear out of the semicircular canal in order to treat benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. CRT has 5 key elements:

- Premedication of the patient

- Specific positions

- Timing of shifts between positions

- Use of vibration

- Post-maneuver instructions

Early attempts to treat BBPV involved similar processes that were believed to be habituation exercises, but more likely dislodged and dissolved debris.[2]

Treatment of vestibular hypofunction

Vestibular hypofunction can be a unilateral or bilateral vestibular loss. There are three types of vestibular rehabilitation exercises to reduce symptoms in cases where physical dysfunction cannot be reduced. The category of exercises chosen by a vestibular therapist depends on the problems reported by the patient. The following exercises can be used to treat dizziness with fast movements or exposure to intense visual stimuli, difficulty seeing (appearance of bouncing or jumping visual field) with head movement, and trouble with balance.[1]

Habituation

Habituation exercise aims to repeatedly expose patients to stimuli that provoke dizziness, such as certain motions and harsh visual stimuli. The provoking stimulus will induce dizziness at first, but with continued habituation exercises, the brain can adapt to discount the stimulus and dizziness reduces. As this occurs, the exercises can increase in intensity. The patient should take breaks between exercises when symptoms are experienced, until the symptoms stop.[2]

Gaze stabilization

Gaze stabilization exercises aim to increase visual ability during head movement.[1] The goal of the patient during these exercises is to maintain the gaze during head movement. One kind of gaze stabilization exercise involves looking at a target and moving the head back and forth, without looking away from the target. Another exercise requires looking from one target to another, first without moving the head, and then moving the head to be aligned with the target without shifting the eyes. The last exercise for gaze stabilization is known as the remembered-target exercise and is performed partially with the eyes closed. First, the patient looks at a target object directly in front of them. Next, the patient closes their eyes and turns their head and turns it back. When the patient opens their eyes, they should still be looking at the target object.[2]

Balance training

Balance-training exercises (also known as postural-stabilization exercises) are designed to improve a patient's ability to stay upright, and reduce the likelihood of dangerous falls.[1] Balance-training exercises can be done walking or standing and can incorporate head movements and habituation exercises to limit exacerbation of symptoms. Increased postural stability can be achieved using visual and somatosensory cues. Thus, exercises in this category challenge the body's use of these cues by limiting or changing them. For example, having the patient close their eyes limits their ability to rely on visual cues to maintain postural stability, while having the patient stand on foam alters their reliance on somatosensory signals.[2]

Effectiveness

The limitations of vestibular rehabilitation therapy are the overall health and function of the nervous system, especially the brainstem, cerebellum, and visual and somatosensory centers.[1] The ultimate goal of vestibular rehabilitation therapy is reduction of vertigo, dizziness, gaze instability, poor balance, and dangerous falls; in some cases this goal is achieved without reducing dysfunction.

Other factors that determine the effectiveness of vestibular rehabilitation are behavioral ones, such as patient compliance to home exercises and limitations in daily life; the severity of the disorder (including unilateral versus bilateral dysfunction); the mental-emotional state of the patient, and other medical conditions and medications.[1] Research has shown that, overall, 80 to 85 percent of patients with chronic vestibular disability reported a reduction in symptoms after VR.[8]

There is evidence that vestibular rehabilitation therapy increases the "balance, quality of life, and functional capacity" of patients with multiple sclerosis.[6]

In a study of 109 children, an association between completion of vestibular rehabilitation and improvement of concussion symptoms and visuovestibular performance was found. A different study found that vestibular and physical therapy were linked to a shorter recovery period, resulting in a more rapid return to sports.[5]

Training and certification

Vestibular rehabilitation can be facilitated by a medical professional with a specialization in neurology or vestibular disorders. An official specialist certification is not required, and in many places, is not offered. The leading association of physical therapists in each country determines what disciplines have specialization status and the requirements of an individual to obtain certification in a specialty.

In the US

Members of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) who undergo specialist certification in neurology via the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties (ABPTS) can administer vestibular rehabilitation exercises.[9] While the APTA does not offer official certification in vestibular rehabilitation, it does offer courses regarding vestibular rehabilitation at introductory and advanced levels. The Academy of Neurologic Physical Therapy and the Vestibular Rehabilitation Special Interest Group are working to have the APTA establish VR as an official specialty offered by the ABPTS.[10]

The American Musculoskeletal Institute (AMSI) offers a 3-day course that results in a therapist being designated a Certified Vestibular Rehabilitation Specialist (Cert. VRS).[11]

Members of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) who obtain specialty certification in low-vision rehabilitation are equipped to treat vision issues that arise from vestibular dysfunction or disorders.[12]

In Canada

The Canadian Physiotherapy Association offers vestibular rehabilitation therapy courses, but does not recognize vestibular rehabilitation as a specialist certification. Similar to the ABPTS, the CPA's Clinical Specialty Program allows Canadian physiotherapists to specialize in neurosciences. Physical therapists with this specialization may be more equipped to administer vestibular treatment than those without it.[13]

See also

References

- Farrell, Lisa (2015). "Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT)". Vestibular Disorders Association.

- Herdman, Susan J.; Clendaniel, Richard A. (2014-07-24). Vestibular rehabilitation (Fourth ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. ISBN 978-080364081-8. OCLC 885123823.

- Bhattacharyya, Neil; Gubbels, Samuel P.; Schwartz, Seth R.; Edlow, Jonathan A.; El-Kashlan, Hussam; Fife, Terry; Holmberg, Janene M.; Mahoney, Kathryn; Hollingsworth, Deena B.; Roberts, Richard; Seidman, Michael D. (March 2017). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update)". Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 156 (3_suppl): S1–S47. doi:10.1177/0194599816689667. ISSN 1097-6817. PMID 28248609.

- "Medication". Vestibular Disorders Association. 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- Storey, Eileen P.; Wiebe, Douglas J.; DʼAlonzo, Bernadette A.; Nixon-Cave, Kim; Jackson-Coty, Janet; Goodman, Arlene M.; Grady, Matthew F.; Master, Christina L. (July 2018). "Vestibular Rehabilitation Is Associated With Visuovestibular Improvement in Pediatric Concussion". Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 42 (3): 134–141. doi:10.1097/npt.0000000000000228. ISSN 1557-0576. PMID 29912034.

- Ozgen, Gulnur; Karapolat, Hale; Akkoc, Yesim; Yuceyar, Nur (August 2016). "Is customized vestibular rehabilitation effective in patients with multiple sclerosis? A randomized controlled trial". European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 52 (4): 466–478. ISSN 1973-9095. PMID 27050082.

- Bhattacharyya, Neil; Gubbels, Samuel P.; Schwartz, Seth R.; Edlow, Jonathan A.; El-Kashlan, Hussam; Fife, Terry; Holmberg, Janene M.; Mahoney, Kathryn; Hollingsworth, Deena B.; Roberts, Richard; Seidman, Michael D. (March 2017). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update)". Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 156 (3_suppl): S1–S47. doi:10.1177/0194599816689667. ISSN 1097-6817. PMID 28248609.

- Shepard, Neil T.; Smith-Wheelock, Michael; Telian, Steven A.; Raj, Anil (March 1993). "Vestibular and Balance Rehabilitation Therapy". Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 102 (3): 198–205. doi:10.1177/000348949310200306. ISSN 0003-4894. PMID 8457121.

- "Specialist Certification Examination Outline: Neurology". American Board of Physical Therapy Specialities.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". www.neuropt.org. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- "Vestibular Rehab Specialist Certification - Manual Physical Therapy Alliance". Manual Physical Therapy Alliance. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

- "Specialty Certification in LOW VISION". The American Occupational Therapy Association.

- "Clinical Specialty Program | Canadian Physiotherapy Association". physiotherapy.ca. Retrieved 2018-11-25.