Magistrate for Health

The Magistrate for Health (Italian: Magistrato alla Sanità) was a magistracy of the Republic of Venice instituted in 1485 to manage public health in the city of Venice and its territories, with specific attention on preventing the spread of epidemics within the maritime republic. The magistracy was expanded several times, notably in 1556 with the introduction of a supervisory role and in 1563 with a regulatory body. It was among the first health authorities in Europe to institute public inoculation projects to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. The office of the Magistrate for Health was retained until the Fall of the Republic of Venice, during which it was briefly replaced by a health committee and eventually superseded by other magistracies entirely.

Organisation

The Magistrate for Health initially comprised three superintendents appointed by the Venetian Senate, but fell under the jurisdiction of the Great Council of Venice in 1537. In 1556, it was expanded with two supervisors tasked with directing and controlling the work of the superintendents in the name of the Republic. In 1563, a regulatory body for the activities of the Magistrate for Health was introduced in the form of a college of ten “wise men” (Italian: Savi) who were elected individually by the Venetian Senate.[1]

The authority of the Magistrate for Health extended not only to the entirety of the Venetian Lagoon but also to the other cities of the Venetian Republic by means of establishing health offices in each. Extensive infrastructure was introduced in the Ionian Islands, which were viewed particularly throughout the 17th and 18th centuries as likely sources of disease outbreaks due to its proximity to Asia Minor and by extension the Ottoman Empire. [2]

During the Fall of the Republic of Venice, as Napoleon’s troops were occupying the Republic’s territory with numerous reforms to government and infrastructure, the office of the Magistrate for Health was folded into the Health Committee (Italian: Comitato di Sanità) for a short period of time before eventually being disbanded, with its duties assigned to other magistracies.

Function

Upon its institution as a permanent body, the Magistrate for Health was tasked with safeguarding the public health of the state, with particular attention to preventing the spread of foreign diseases within the republic’s territory, a regular threat for a city with such extensive reliance on trade routes bearing risk of contact with foreign outbreaks (notably in the 1347 outbreak of the Black Death, in which Venice’s interactions with seagoing vessels had made it one of the first cities in Europe to be devastated by the plague). In order to do so, the superintendents (and upon their introduction, the supervisors) were empowered with numerous legal authorities, including the right to pronounce capital punishment, ostensibly for purposes of quarantine.

The officials of the Magistrate for Health exercised their authority in supervising a wide range of professions and services: in addition to the colleges of barbers and physicians, it regularly supervised the food industry, lazar houses, waste disposal, sewage and water management and mortuary services. It was also known to interact with prostitutes, vagrants, beggars and guesthouses, further aiding the surveillance of possible transmission of foreign maladies within their jurisdiction. However, in many cases, their authority was often not direct; for example, the lazar houses, or lazaretti, were able to bypass local health authorities and report directly to the regional government in times of low disease activity, only falling under the health office’s direct jurisdiction in times of emergency.[3]

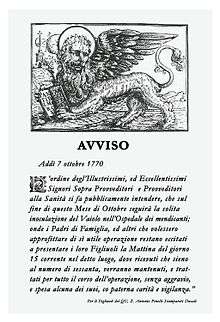

The Venetian Magistrate for Health was the second health provider in Italy to introduce variolation, which had only recently been introduced to Europe from eastern schools of medicine, as a means of inoculation against smallpox, preceded only by the Hospital of Santa Maria degli Innocenti in Florence, and the first to offer it freely to the public for purposes of herd immunity.

Despite their precautions, epidemics continued to occur regularly in Venice. The outbreak of plague of 1576–1577 killed around 50,000 in Venice, almost a third of the population;[4] a similar proportion of the population was killed in 1630 in the Italian plague of 1629-31, when around 46,000 of the city’s 140,000 citizens were killed.[5] In order to enable control and quarantine of disease outbreaks, officials of the Magistrate for Health were able to impose periods of isolation of at least 14 days, upper length dependent on the situation in the port of question, and to cordon off areas of the city. Independent branches of the Venetian health services immediately discontinued trade and travel to and from Venice, functioning independently with the immediate isolation order of the Venetian Senate until the outbreak abated. Other methods of disease control included an intricate network of information and messaging, allowing for efficient reporting of and response to outbreaks, and the capacity to mobilise local coastal garrisons to carry out inspections, allowing isolation of plague-infested areas using pre-existing infrastructure.[2]

Archive

The Archive of the Superintendents for Health contains nearly four centuries of documentation on not only the conditions of public health and sanitation within the Venetian Republic, but also of other contemporary states, on account of the extensive information gathered by the officials from their foreign counterparts as part of their regular surveillance of potential foreign-borne epidemics. The inventory for the archive, along with an index of names and locations, was published by Salvatore Carbone in 1962.[6]

Bibliography

- Andrea da Mosto. The Archive of the State of Venice. (Italian: L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia). General index, history, description and analysis

- Antonio Semprini, History of smallpox (Storia del vaiolo).

- Nelli-Elena Vanzan Marchini, L'esercizio dell'assistenza e il corpo anfibio, in Sanità e Società, Veneto, Lombardia, Piemonte, Liguria, secoli XVII-XX a cura di F. Della Peruta, Casamassima, Udine 1989, pp. 17-35

- Le leggi di sanità della Repubblica di Venezia, a cura di N.E. Vanzan Marchini, volumi 5, I, II, Neri Pozza, Vicenza 1995,1998, III, IV e Indici, Canova, Treviso 2000, 2003, 2012.

- Nelli-Elena Vanzan Marchini, I mali e i rimedi della Serenissima, Neri Pozza, Vicenza 1995.

- Nelli-Elena Vanzan Marchini (ed.), Rotte mediterranee e baluardi di sanità, Skira, Milano Ginevra 2004.

- Nelli-Elena Vanzan Marchini, Venezia e i lazzaretti Mediterranei, (catalogo della mostra nella Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana 2004) Edizioni della laguna, Mariano del Friuli 2004.(anche in edizione inglese)

- Nelli-Elena Vanzan Marchini, Venezia, la salute e la fede, De Bastiani, Vittorio Veneto 2011.

- Nelli-Elena Vanzan Marchini, Venezia e Trieste sulle rotte della ricchezza e della paura. Cierre, Verona 2016.

References

- "Great Council | Venetian political organization". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- Katerina Konstantinidou, Elpis Mantadakis, Matthew E. Falagas, Thalia Sardi & George Samonis (2009). "Venetian rule and control of plague epidemics on the Ionian Islands during 17th and 18th centuries". Emerging infectious diseases. 15 (1): 39–43. doi:10.3201/eid1501.071545. PMC 2660681. PMID 19116047.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Konstantinidou, Katerina (2007). The disaster creeps crawling… The plague epidemics of the Ionian Islands (in Greek). Venice (Italy): Hellenic Institute of Byzantine and Post Byzantine Studies. pp. 55–203.

- "Medicine and society in early modern Europe". Mary Lindemann (1999). Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-521-42354-6.

- Hays, J. N. (2005). Epidemics and pandemics their impacts on human history. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 103. ISBN 978-1851096589.

- Carbone, Salvatore. Provveditori e Sopraprovveditori alla Sanità della Repubblica di Venezia. Carteggio con i rappresentanti diplomatici e consolari veneti all'estero e con uffici di Sanità esteri corrispondenti. (Inventory). Rome: 1962, pp. 92 (Quaderni della Rassegna degli Archivi di Stato, 21).