Vaping-associated pulmonary injury

Vaping-associated pulmonary injury (VAPI)[4] also known as vaping-associated lung injury (VALI)[1] or e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI),[2] is a lung disease associated with the use of vaping products that can be severe and life-threatening.[3] Symptoms can initially mimic common pulmonary diagnoses like pneumonia, but individuals typically do not respond to antibiotic therapy.[4] Individuals usually present for care within a few days to weeks of symptom onset.[4]

| Vaping-associated pulmonary injury | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vaping-associated lung injury,[1] e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI)[2] |

| |

| CT scan of the chest showing diffuse lung infiltrates found in three cases of vaping-associated pulmonary injury. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology, Intensive care medicine |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, hypoxia, fever, cough, diarrhea |

| Causes | Unknown types of vaping |

| Diagnostic method | Chest X-ray, CT Scan |

| Treatment | Corticosteroids, Oxygen therapy |

| Deaths | 47 U.S. (2,290 cases U.S.)[3] |

In September 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported an outbreak of severe lung disease linked to vaping,[5] or the process of inhaling aerosolized substances with battery-operated electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes),[6] ciga-likes, or vape mods.[7] The cases of lung injury date back to at least April 2019.[8] The on-going investigation into this multi-state outbreak of lung injury linked to the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products involves the CDC, the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA), state and local health departments, and other clinical and public health partners.[3] As of November 13, 2019, 2,172 cases of VAPI have been reported to the CDC from 49 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands, with 42 confirmed deaths from 24 states and the District of Columbia.[3]

All CDC-reported cases of VAPI involve a history of using e-cigarette, or vaping, products, with most samples testing positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) by the US FDA to date and most patients reporting a history of using a THC-containing product.[3] The CDC says that the additive vitamin E acetate is a very strong culprit of concern in VAPI,[9] but evidence is not yet sufficient to rule out contribution of other chemicals of concern to VAPI.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Commonly reported symptoms include shortness of breath, cough, fatigue, body aches, fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.[4] Additional symptoms may include chest pain, abdominal pain, chills, or weight loss.[10] Symptoms can initially mimic common pulmonary diagnoses like pneumonia, but individuals typically do not respond to antibiotic therapy.[4] In some patients, gastrointestinal symptoms can precede respiratory symptoms.[2] Individuals typically present for care within a few days to weeks of symptom onset.[4] At the time of hospital presentation, the individual is often hypoxic and meets systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria, including fever.[4] Physical exam can reveal rapid heart rate or rapid breathing.[8] Auscultation of the lungs tends to be unremarkable, even in patients with severe lung disease.[2] In some cases, the affected individuals have progressive respiratory failure, leading to intubation.[4] Several affected individuals have needed to be placed in the intensive care unit (ICU) and on mechanical ventilation.[5] Time to recovery for hospital discharge has ranged from days to weeks.[4]

Mechanism

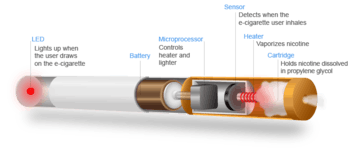

Vaping refers to the practice of inhaling an aerosol from an electronic cigarette device,[4] which works by heating a liquid that can contain various substances, including nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), flavoring, and additives (eg. glycerin, propylene glycol).[7] The long-term health impacts of vaping are unknown.[4]

Most individuals treated for VAPI report vaping the cannabis compounds THC and/or cannabidiol (CBD), and some also report vaping nicotine products.[4] In addition to vaping, some individuals have also experienced VAPI through "dabbing."[4] Dabbing uses a different type of device to heat and extract cannabinoids for inhalation.[4] It is a process that entails superheating and inhaling particles into the lungs that contain THC and other types of cannabidiol plant materials.[11]

VAPI appears to be a type of acute lung injury, similar to acute fibrinous pneumonitis, organizing pneumonia, or diffuse alveolar damage.[12] VAPI appears to be a general term for various causes of acute lung damage due to vaping.[13] There is no evidence of an infectious etiology causing VAPI.[10]

No single compound or ingredient has emerged as the cause of these illnesses as of November 2019.[3] Many different substances and product sources are still under investigation.[3] The CDC stated that the latest national and state findings suggest products containing THC, particularly from informal sources like friends, family, or in-person or online dealers, are linked to most of the cases and play a major role in the outbreak.[3] The CDC states that vitamin E acetate is a very strong culprit of concern in VAPI, having been found in 29 out of 29 lung biopsies tested from ten different states,[9] but evidence is not yet sufficient to rule out contribution of other chemicals of concern to VAPI.[3] The CDC states that previous research suggests inhaled vitamin E acetate may interfere with normal lung functioning.[3] It is possible that there is more than one substance causing this outbreak.[3]

Diagnosis

High clinical suspicion is necessary to make the diagnosis of VAPI.[4] Currently, VAPI is considered a diagnosis of exclusion because no specific tests or markers exist for its diagnosis, as of yet.[2] Healthcare providers should evaluate for alternative diagnoses (e.g., cardiac, gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, neoplastic, environmental or occupational exposures, or causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome) as suggested by clinical presentation and medical history, while also considering multiple etiologies, including the possibility of VAPI occurring with a concomitant infection.[2]

All healthcare providers evaluating patients for VAPI should consider obtaining a thorough patient history, including symptoms and recent use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products, along with substances used, duration and frequency of use, and method of use.[2] Additionally a detailed physical examination, including vital signs and pulse-oximetry should be performed.[2] Laboratory testing guided by clinical findings, which may include a respiratory virus panel to rule out infectious diseases, complete blood count with differential, serum inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]), liver transaminases, and urine toxicology testing, including testing for THC should be acquired.[2] Imaging, typically a chest x-ray, with consideration for a chest CT if chest x-ray results do not correlate with the clinical picture or to evaluate severe or worsening disease should be obtained.[2] Consulting with specialists (eg. critical care, pulmonology, medical toxicology, or infectious disease) can help guide further evaluation.[2] The diagnosis is commonly suspected when the person does not respond to antibiotic therapy, and testing does not reveal an alternative diagnosis.[4] Many of the reported cases involved worsening respiratory failure within 48 hours of admission after the administration of empiric antibiotic therapy.[14] Lung biopsies are not necessary for the diagnosis but are performed as clinically indicated to rule out the likelihood of infection.[11]

There are non-specific laboratory abnormalities that have been reported in association with the disease, including elevations in white blood cell count (with neutrophilic predominance and absence of eosinophilia), transaminases, procalcitonin, and inflammatory markers.[4][14] Infectious disease testing, including blood and sputum cultures and tests for influenza, Mycoplasma, and Legionella were all found to be negative in the majority of reported cases.[14] Imaging abnormalities are typically bilateral and are usually described as "pulmonary infiltrates or opacities" on chest x-ray and "ground-glass opacities" on chest CT.[4] Bronchoalveolar lavage specimens may exhibit an increased level of neutrophils in combination with lymphocytes and vacuole-laden macrophages.[5] Lavage cytology with oil red O staining demonstrated extensive lipid-laden alveolar macrophages.[14][15] In the few cases in which lung biopsies were performed, the results were consistent with acute lung injury and included a broad range of features, such as acute fibrinous pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar damage, lipid-laden macrophages, and organizing pneumonia.[8][11] Lung biopsies often showed neutrophil predominance as well, with rare eosinophils.[12]

Case definitions

Based on the clinical characteristics of VAPI cases from ongoing federal and state investigations, interim surveillance case definitions for confirmed and probable cases have been developed.[2]

CDC surveillance case definition for confirmed cases of severe pulmonary disease associated with e-cigarette use:[16]

- Using an e-cigarette ("vaping") or dabbing during the 90 days before symptom onset AND[16]

- Pulmonary infiltrate, such as opacities on plain film chest radiograph or ground-glass opacities on chest computed tomography AND[16]

- Absence of pulmonary infection on initial work-up. Minimum criteria include:[16]

- A negative respiratory viral panel[16]

- A negative influenza polymerase chain reaction or rapid test if local epidemiology supports testing.[16]

- All other clinically indicated respiratory infectious disease testing (e.g., urine antigen for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella, sputum culture if productive cough, bronchoalveolar lavage culture if done, blood culture, human immunodeficiency virus–related opportunistic respiratory infections if appropriate) must be negative AND[16]

- No evidence in medical record of alternative plausible diagnoses (e.g., cardiac, rheumatologic, or neoplastic process).[16]

CDC surveillance case definition for probable cases of severe pulmonary disease associated with e-cigarette use:[16]

- Using an e-cigarette ("vaping") or dabbing in 90 days before symptom onset AND[16]

- Pulmonary infiltrate, such as opacities on plain film chest radiograph or ground-glass opacities on chest computed tomography AND[16]

- Infection identified via culture or polymerase chain reaction, but clinical team believes this is not the sole cause of the underlying respiratory disease process OR minimum criteria to rule out pulmonary infection not met (testing not performed) and clinical team believes this is not the sole cause of the underlying respiratory disease process AND[16]

- No evidence in medical record of alternative plausible diagnoses (e.g., cardiac, rheumatologic, or neoplastic process).[16]

These surveillance case definitions are meant for public health data collection purposes and are not intended to be used as a clinical diagnostic tool or to guide clinical care; they are subject to change and will be updated as additional information becomes available.[16]

Differential diagnosis

As VAPI is currently a diagnosis of exclusion, a variety of respiratory diseases must be ruled out before a diagnosis of VAPI can be made.[2] The differential diagnosis should include more common diagnostic possibilities, such as community-acquired pneumonia, as well as do-not-miss diagnoses, such as pulmonary embolism.[2] Other commonly documented hospital diagnoses for cases of severe pulmonary disease associated with e-cigarette use have included acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, acute hypoxic respiratory failure, and pneumonitis.[4] Currently, distinctions between processes occurring in association with vaping or the use of nicotine-containing liquids and those considered as alternative diagnoses to VAPI are still being made.[8] These processes include the following:

- Acute eosinophilic pneumonia[8]

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis[8][17]

- Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease[8]

- Organizing pneumonia[8][17]

- Lipoid pneumonia[15][17]

- Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage[8][17]

- Giant cell pneumonitis[17]

The use of imaging and other diagnostic modalities, including chest CT, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage, and lung biopsy, may provide additional information to determine the presence of these processes and potentially establish a definitive diagnosis, but are generally not performed unless clinically indicated.[2]

Treatment

As of October 18, 2019, the CDC has published updated interim guidance based on the most current data to provide a framework for healthcare providers in their management and follow-up of persons with symptoms of VAPI.[2] Initial management involves deciding whether to admit a patient with possible VAPI to the hospital. Currently, the CDC recommends that patients with suspected VAPI should be admitted if they have decreased O2 saturation (<95%) on room air, are in respiratory distress, or have comorbidities that compromise pulmonary reserve.[2] Once admitted, initiation of corticosteroids should be considered, which have been found to be helpful in treating this injury.[2] Several case reports describe improvement with corticosteroids, likely because of a blunting of the inflammatory response.[2] In a group of patients in Illinois and Wisconsin, 92% of 50 patients received corticosteroids, and those that began glucocorticoid therapy continued on it for at least 7 days.[8] The medical team documented in 65% of 46 patient notes that "respiratory improvement was due to the use of glucocorticoids".[8] Among 140 cases reported nationally to CDC that received corticosteroids, 82% of patients improved.[2] In patients with more severe illness, a more aggressive empiric therapy with corticosteroids as well as antimicrobial and antiviral therapy may be warranted.[2]

As a large proportion of patients were admitted to an intensive care unit based on data submitted to CDC, many patients require supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula, high-flow oxygen, bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), or mechanical ventilation.[4]

During influenza season, health care providers should consider influenza in all patients with suspected VAPI.[18] Decisions on initiation or discontinuation of treatment should be based on specific clinical features and, when appropriate, in consultation with specialists.[18]

Special consideration should be given to high-risk patients such as the elderly, those with history of cardiac or lung disease, or pregnant individuals.[2] Patients over 50 years old have an increased risk of intubation and might need longer hospitalizations.[2]

Follow-up care

Due to reports of relapse during corticosteroid tapers after hospitalization, the CDC recommends scheduling a follow-up visit no later than 1-2 weeks after discharge from inpatient hospital treatment from VAPI, with considerations for performing pulse-oximetry testing and repeat CXR.[2] In 1-2 months, healthcare providers should consider additional follow-up testing, including spirometry, diffusion capacity testing, and another repeat CXR.[2] In patients with persistent hypoxemia (O2 saturation <95%) requiring home oxygen at discharge, consider ongoing pulmonary follow-up.[2] In patients treated with high-dose corticosteroids, consider endocrinology follow-up to monitor adrenal function.[2]

As it is unknown whether patients with a history of VAPI are at increased risk for severe complications with influenza or other respiratory infections, follow-up care should also include annual vaccination against influenza for all persons over 6 months of age, including patients with a history of EVALI, as well as administration of the pneumococcal vaccine according to current guidelines.[2]

An important part of both inpatient and follow-up care for VAPI involves advising patients to discontinue use of e-cigarette or vaping products.[19]

Public health recommendations

As national and state data suggest that THC-containing products are linked to most of the reported VAPI cases and likely play a major role in the outbreak, the CDC has made the following recommendations:[2]

- Persons should not use e-cigarette, or vaping, products that contain THC.[2]

- Persons should not buy any type of e-cigarette, or vaping, products, particularly those containing THC, off the street.[2]

- Persons should not modify or add any substances to e-cigarette, or vaping, products that are not intended by the manufacturer, including products purchased through retail establishments.[2]

Given the possibility that nicotine-containing products are also playing a role in the outbreak, the CDC continues to recommend that persons consider refraining from using e-cigarette, or vaping, products that contain nicotine.[2]

As the investigation into the outbreak of VAPI continues, the CDC encourages healthcare providers to continue to report cases of lung injury linked to the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products within the past 90 days to local or state health departments.[18]

Epidemiology

As of November 13, 2019, there have been 2,172 cases of VAPI reported from 49 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands.[3] The CDC has received complete gender and age data on these cases with 70% of cases being male.[3] The median age of cases is 24 years and ranges from 13 to 75 years.[3] 79% of cases are under 35 years old.[3] There have been 42 confirmed deaths in 24 states and the District of Columbia from this outbreak ranging from ages 17-75 years old.[3]

Of the 2,051 cases reported to the CDC, information on substance use is known for 867 cases in the three months prior to symptom onset as of October 15, 2019.[3] About 86% reported using THC-containing products; 34% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products.[3] About 64% reported using nicotine-containing products; 11% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.[3]

On September 28, 2019, the first case of vaping-associated pulmonary injury was identified in Canada.[20] A number of other probable cases have been reported in British Columbia and New Brunswick as of October 2019.[21]

In September 2019, a US Insurance Journal article stated that at least 15 incidents of vaping related illnesses have been reported worldwide prior to 2019, occurring from Guam to Japan to the UK to the US.[22] 12 cases of health problems with nicotine-containing e-cigarettes were reported to the UK's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), with at least one case bearing high similarities to the lipid pneumonia cases reported in the US.[22] One lipoid pneumonia-related death in the UK was associated with e-cigarettes in 2010,[23] and in a second death in the UK associated with e-cigarettes in 2012, a heart attack was determined to be the cause of death.[24]

Medical officials in continental Europe have not reported any serious medical problems related to vaping products except one early case related to e-cigarettes documented in Northern Spain in 2015. Since many of the cases in North America were traced to THC-cartridges as well as the use of e-cigarette vape products, but THC remains illegal in European countries, the disease burden related to vaping has been significantly lower in Europe despite the prevalence of e-cigarette use.[25]

Other names

Vaping-associated pulmonary injury (VAPI)[4] is also variously known as e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI),[2] vaping-associated lung injury,[1] vaping-associated lung disease,[17] vaping-induced lung injury,[26] vaping-induced pulmonary disease,[27] vaping associated respiratory syndrome,[7] vape-related lung disease,[28] vape-related lung illness,[29] vape-related pulmonary illness,[30] vaporizer-linked respiratory failure,[31] vaping-linked lung illness,[32] or vape lung.[33]

References

- "Vaping-Associated Lung Injuries". Minnesota Department of Health. 24 September 2019.

- Siegel, David A.; Jatlaoui, Tara C.; Koumans, Emily H.; Kiernan, Emily A.; Layer, Mark; Cates, Jordan E.; Kimball, Anne; Weissman, David N.; Petersen, Emily E.; Reagan-Steiner, Sarah; Godfred-Cato, Shana; Moulia, Danielle; Moritz, Erin; Lehnert, Jonathan D.; Mitchko, Jane; London, Joel; Zaki, Sherif R.; King, Brian A.; Jones, Christopher M.; Patel, Anita; Delman, Dana Meaney; Koppaka, Ram; Griffiths, Anne; Esper, Annette; Calfee, Carolyn S.; Hayes, Don; Rao, Devika R.; Harris, Dixie; Smith, Lincoln S.; Aberegg, Scott; Callahan, Sean J.; Njai, Rashid; Adjemian, Jennifer; Garcia, Macarena; Hartnett, Kathleen; Marshall, Kristen; Powell, Aaron Kite; Adebayo, Adebola; Amin, Minal; Banks, Michelle; Cates, Jordan; Al-Shawaf, Maeh; Boyle-Estheimer, Lauren; Briss, Peter; Chandra, Gyan; Chang, Karen; Chevinsky, Jennifer; Chiang, Katelyn; Cho, Pyone; DeSisto, Carla Lucia; Duca, Lindsey; Jiva, Sumera; Kaboré, Charlotte; Kenemer, John; Lekiachvili, Akaki; Miller, Maureen; Mohamoud, Yousra; Perrine, Cria; Shamout, Mays; Zapata, Lauren; Annor, Francis; Barry, Vaughn; Board, Amy; Evans, Mary E.; Gately, Allison; Hoots, Brooke; Pickens, Cassandra; Rogers, Tia; Vivolo-Kantor, Alana; Cyrus, Alissa; Boehmer, Tegan; Glidden, Emily; Hanchey, Arianna; Werner, Angela; Zadeh, Shideh Ebrahim; Pickett, Donna; Fields, Victoria; Hughes, Michelle; Neelam, Varsha; Chatham-Stephens, Kevin; O’Laughlin, Kevin; Pomeroy, Mary; Atti, Sukhshant K.; Freed, Jennifer; Johnson, Jona; McLanahan, Eva; Varela, Kate; Layden, Jennifer; Meiman, Jonathan; Roth, Nicole M.; Browning, Diane; Delaney, Augustina; Olson, Samantha; Hodges, Dessica F.; Smalley, Raschelle; et al. (Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group) (October 2019). "Update: Interim Guidance for Health Care Providers Evaluating and Caring for Patients with Suspected E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use Associated Lung Injury — United States, October 2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (41): 919–927. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6841e3. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 6802682. PMID 31633675.

- "Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with E-Cigarette Use, or Vaping". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 21 November 2019.

- "CDPH Health Alert: Vaping-Associated Pulmonary Injury" (PDF). California Tobacco Control Program. California Department of Public Health. 28 August 2019. pp. 1–5.

- Carlos, W. Graham; Crotty Alexander, Laura E; Gross, Jane E; Dela Cruz, Charles S; Keller, Jonathan M; Pasnick, Susan; Jamil, Shazia (October 2019). "Vaping Associated Pulmonary Illness (VAPI)". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 200 (7): P13–P14. doi:10.1164/rccm.2007P13. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 31532695.

- Triantafyllou, Georgios A.; Tiberio, Perry J.; Zou, Richard H.; Lamberty, Phillip E.; Lynch, Michael J.; Kreit, John W.; Gladwin, Mark T.; Morris, Alison; Chiarchiaro, Jared (October 2019). "Vaping-Associated Acute Lung Injury: A Case Series". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 200 (11): 1430–1431. doi:10.1164/rccm.201909-1809LE. ISSN 1535-4970. PMID 31574235.

- Gotts, Jeffrey E; Jordt, Sven-Eric; McConnell, Rob; Tarran, Robert (2019). "What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes?". BMJ. 366: l5275. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5275. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 31570493.

- Layden, Jennifer E.; Ghinai, Isaac; Pray, Ian; Kimball, Anne; Layer, Mark; Tenforde, Mark; Navon, Livia; Hoots, Brooke; Salvatore, Phillip P.; Elderbrook, Megan; Haupt, Thomas; Kanne, Jeffrey; Patel, Megan T.; Saathoff-Huber, Lori; King, Brian A.; Schier, Josh G.; Mikosz, Christina A.; Meiman, Jonathan (September 2019). "Pulmonary Illness Related to E-Cigarette Use in Illinois and Wisconsin — Preliminary Report". The New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911614. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31491072.

- "Transcript of CDC Telebriefing: Update on Lung Injury Associated with E-cigarette Use, or Vaping". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 8 November 2019.

- "For the Public: What You Need to Know". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 28 October 2019.

- Mukhopadhyay, Sanjay; Mehrad, Mitra; Dammert, Pedro; Arrossi, Andrea V; Sarda, Rakesh; Brenner, David S; Maldonado, Fabien; Choi, Humberto; Ghobrial, Michael (October 2019). "Lung Biopsy Findings in Severe Pulmonary Illness Associated With E-Cigarette Use (Vaping): A Report of Eight Cases". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqz182. ISSN 0002-9173. PMID 31621873.

- Butt, Yasmeen M.; Smith, Maxwell L.; Tazelaar, Henry D.; Vaszar, Laszlo T.; Swanson, Karen L.; Cecchini, Matthew J.; Boland, Jennifer M.; Bois, Melanie C.; Boyum, James H.; Froemming, Adam T.; Khoor, Andras; Mira-Avendano, Isabel; Patel, Aiyub; Larsen, Brandon T. (October 2019). "Pathology of Vaping-Associated Lung Injury". The New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (18): 1780–1781. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1913069. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31577870.

- Boland, Jennifer M; Aesif, Scott W (October 2019). "Vaping-Associated Lung Injury". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqz191. ISSN 0002-9173. PMID 31651033.

- Davidson, Kevin; Brancato, Alison; Heetderks, Peter; Mansour, Wissam; Matheis, Edward; Nario, Myra; Rajagopalan, Shrinivas; Underhill, Bailey; Wininger, Jeremy; Fox, Daniel (13 September 2019). "Outbreak of Electronic-Cigarette–Associated Acute Lipoid Pneumonia — North Carolina, July–August 2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (36): 784–786. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 6755817. PMID 31513559.

- Maddock, Sean D.; Cirulis, Meghan M.; Callahan, Sean J.; Keenan, Lynn M.; Pirozzi, Cheryl S.; Raman, Sanjeev M.; Aberegg, Scott K. (10 October 2019). "Pulmonary Lipid-Laden Macrophages and Vaping". The New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (15): 1488–1489. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1912038. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31491073.

- Schier, Joshua G.; Meiman, Jonathan G.; Layden, Jennifer; Mikosz, Christina A.; VanFrank, Brenna; King, Brian A; Salvatore, Phillip P.; Weissman, David N.; Thomas, Jerry; Melstrom, Paul C.; Baldwin, Grant T.; Parker, Erin M.; Courtney-Long, Elizabeth A.; Krishnasamy, Vikram P.; Pickens, Cassandra M.; Evans, Mary E.; Tsay, Sharon V.; Powell, Krista M.; Kiernan, Emily A.; Marynak, Kristy L.; Adjemian, Jennifer; Holton, Kelly; Armour, Brian S.; England, Lucinda J.; Briss, Peter A.; Houry, Debra; Hacker, Karen A.; Reagan-Steiner, Sarah; Zaki, Sherif; Meaney-Delman, Dana; et al. (CDC 2019 Lung Injury Response Group.) (2019). "Severe Pulmonary Disease Associated with Electronic-Cigarette–Product Use — Interim Guidance". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (36): 787–790. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e2. ISSN 0149-2195. PMC 6755818. PMID 31513561.

- Henry, Travis S.; Kanne, Jeffrey P.; Kligerman, Seth J. (September 2019). "Imaging of Vaping-Associated Lung Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (15): 1486–1487. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1911995. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31491070.

- "For Healthcare Providers". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 October 2019.

- Henry, Travis S.; Kligerman, Seth J.; Raptis, Constantine A.; Mann, Howard; Sechrist, Jacob W.; Kanne, Jeffrey P. (October 2019). "Imaging Findings of Vaping-Associated Lung Injury". American Journal of Roentgenology: 1–8. doi:10.2214/AJR.19.22251. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 31593518.

- "Quebec resident confirmed as first Canadian case of vaping-related illness". cbc. 27 September 2019.

- "First probable case of vaping-related illness confirmed in B.C." CBC. 16 October 2019.

- Langreth, Robert; Etter, Lauren (30 September 2019). "How Early Signs of Lung Effects of Vaping Were Missed and Downplayed". Insurance Journal.

- Rodger, James (1 October 2019). "Brit suspected to be first to die from condition linked to vaping". Coventry Telegraph.

- Costello, Emma (11 March 2019). "Fears around vaping grow as another vape-user death reported". Extra.ie.

- Wheaton, Sarah (12 September 2019). "Europe's missing 'vaping sickness'". Politico.

- Christiani, David C. (September 2019). "Vaping-Induced Lung Injury". The New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1912032. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31491071.

- Hswen, Yulin; Brownstein, John S. (2019). "Real-Time Digital Surveillance of Vaping-Induced Pulmonary Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (18): 1778–1780. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1912818. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31539466.

- Fentem, Sarah (4 October 2019). "As More People Die After Using Vaping Products, St. Louis Doctor Warns Of The Risks". KWMU.

- Naftulin, Julia (6 September 2019). "A number of vape-related lung illnesses are linked to 'Dank Vapes,' a mysterious black market brand selling THC products". Insider.

- Bentley, Jimmy (7 October 2019). "First Massachusetts Vape-Related Death Confirmed". Patch Media.

- Kapnick, Izzy (25 October 2019). "Vaping Companies Brace for Wave of Lawsuits Over Lung Illness". Courthouse News Service.

- Mole, Beth (12 September 2019). "Black-market THC-vape operation busted in Wisconsin, police say". Ars Technica.

- Carlos, W. Graham; Crotty Alexander, Laura E; Gross, Jane E; Dela Cruz, Charles S; Keller, Jonathan M; Pasnick, Susan; Jamil, Shazia (October 2019). "ATS Health Alert—Vaping Associated Pulmonary Illness (VAPI)". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 200 (7): P15–P16. doi:10.1164/rccm.2007P15. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 31532698.

Further reading

- "Lung Illnesses Associated with Use of Vaping Products". US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA). 8 November 2019.

- "NEJM — E-Cigarettes and Vaping-Related Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 31 October 2019.

- Corum, Jonathan (21 November 2019). "Vaping Illness Tracker: 2,290 Cases and 47 Deaths". The New York Times.

- Taylor, Joanne; Wiens, Terra; Peterson, Jason; Saravia, Stefan; Lunda, Mark; Hanson, Kaila; Wogen, Matt; D’Heilly, Paige; Margetta, Jamie; Bye, Maria; Cole, Cory; Mumm, Erica; Schwerzler, Lauren; Makhtal, Roon; Danila, Richard; Lynfield, Ruth; Holzbauer, Stacy; Blount, Benjamin C.; Karwowski, Mateusz P.; Morel-Espinosa, Maria; Valentin-Blasini, Liza (26 November 2019). "Characteristics of E-cigarette, or Vaping, Products Used by Patients with Associated Lung Injury and Products Seized by Law Enforcement — Minnesota, 2018 and 2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (47): 1096–1100. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6847e1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMID 31774740.