Vaccination policy in the United States

Vaccination policy in the United States refers to vaccination policy as part of the health policy adopted by various levels of the government of the United States and individual U.S. states in relation to vaccination. This policy has been developed over the approximately two centuries since the invention of vaccination with the purpose of eradicating disease from, or creating a herd immunity for the U.S. population. Policies intended to encourage vaccination impact numerous areas of law, including regulation of vaccine safety, funding of vaccination programs, vaccine mandates, adverse event reporting requirements, and compensation for injuries asserted to be associated with vaccination.

Regulation of vaccine safety

The United States Food and Drug Administration has the authority to enforce the safety of vaccines. The FDA requires that all new vaccines first be tested in laboratory settings and on animals,[2] and must then carry out a series of increasingly stringent tests in human subjects.[3] Once vaccines are introduced to the market, the FDA regularly inspects their production facilities, tests their quality, and receives reports of adverse reactions.

Vaccination schedule and mandates

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices makes scientific recommendations which are generally followed by the federal government, state governments, and private health insurance companies,[4] including making recommendations for the vaccination schedule used in the United States.

All 50 states in the U.S. mandate immunizations for children in order to enroll in public school, but the specific vaccines required differ from state to state and various exemptions are available depending on the state. All states have exemptions for people who have medical contraindications to vaccines, and all states except for California, Maine, Mississippi, New York, and West Virginia allow religious exemptions,[5] while sixteen states allow parents to cite personal, conscientious, philosophical, or other objections.[6] An increasing number of parents are using religious and philosophical exemptions: researchers have cited this increased use of exemptions as contributing to loss of herd immunity within these communities, and hence an increasing number of disease outbreaks.[7][8][9]

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advises physicians to respect the refusal of parents to vaccinate their child after adequate discussion, unless the child is put at significant risk of harm (e.g., during an epidemic, or after a deep and contaminated puncture wound). Under such circumstances, the AAP states that parental refusal of immunization constitutes a form of medical neglect and should be reported to state child protective services agencies.[10]

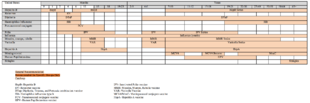

| Infection | Birth | Months | Years | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 19-23 | 2-3 | 4-6 | 7-10 | 11-12 | 13-18 | 19-26 | 27-59 | 60-64 | 65+ | ||

| Hepatitis B | HepB | HepB | HepB | HepB x3 | |||||||||||||||

| Rotavirus | RV | RV | |||||||||||||||||

| Diphtheria | DTaP | DTaP | DTaP | DTaP | DTaP | Tdap | Td (every 10 years) | ||||||||||||

| Tetanus | |||||||||||||||||||

| Pertussis | |||||||||||||||||||

| Haemophilus influenzae | HIB | HIB | HIB | HIB | HIB x1-3 | ||||||||||||||

| Pneumococcus | PCV | PCV | PCV | PCV | PPSV | PPSV | |||||||||||||

| Polio | IPV | IPV | IPV | IPV | |||||||||||||||

| Flu | IIV (yearly) | IIV or LAIV (yearly) | |||||||||||||||||

| Measles | MMR | MMR | MMR x1-2 | MMR | |||||||||||||||

| Mumps | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rubella | |||||||||||||||||||

| Varicella | VV | VV | VV | ||||||||||||||||

| Hepatitis A | HepA x2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Meningococcus | MCV | MCV | MCV x1+ | ||||||||||||||||

| Human papillomavirus | HPV x3 | HPV x31 | |||||||||||||||||

|

Range of recommended ages for everyone. See references for more details.

Range of recommended ages for certain high-risk groups. See references for more details.

Range of recommended ages for catch-up immunization or for people who lack evidence of immunity (e.g., lack documentation of vaccination or have no evidence of prior infection). CDC provides more detailed information in catch-up immunizations.

^1. Note on HPV vaccine: Males who have not yet received 3 doses of HPV4 are generally recommended to have done so through age 21. HPV4 is recommended for men who have sex with men through age 26 years who did not get any or all doses when they were younger. | |||||||||||||||||||

All vaccines recommended by the U.S. government for its citizens are required for green card applicants.[13] This requirement stirred controversy when it was applied to the HPV vaccine in July 2008 due to the cost of the vaccine. In addition, the other thirteen required vaccines prevent highly contagious diseases communicable through the respiratory route, while HPV is only spread through sexual contact.[14] In November 2009, this requirement was canceled.[15]

Though the federal guidelines do not require written consent in order to receive a vaccination, they do require doctors give the recipients or legal representatives a Vaccine Information Statement (VIS). Specific informed consent laws are made by the states.[16][17] Several states allow minors to legally consent to vaccination over parental objections under the mature minor doctrine.

School children

The United States has a long history of school vaccination requirements. The first school vaccination requirement was enacted in the 1850s in Massachusetts to prevent the spread of smallpox.[18] The school vaccination requirement was put in place after the compulsory school attendance law caused a rapid increase in the number of children in public schools, increasing the risk of smallpox outbreaks. The early movement towards school vaccination laws began at the local level including counties, cities, and boards of education. By 1827, Boston had become the first city to mandate that all children entering public schools show proof of vaccination.[19] In addition, in 1855 the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had established its own statewide vaccination requirements for all students entering school, this influenced other states to implement similar statewide vaccination laws in schools as seen in New York in 1862, Connecticut in 1872, Pennsylvania in 1895, and later the Midwest, South and Western US. By 1963, 20 states had school vaccination laws.[19]

These vaccination laws resulted in political debates throughout the United States as those opposed to vaccination sought to repeal local policies and state laws.[20] An example of this political controversy occurred in 1893 in Chicago, where less than 10 percent of the children were vaccinated despite the twelve year old state law.[19] Resistance was seen at the local level of the school district as some local school boards and superintendents opposed the state vaccination laws, leading the state board health inspectors to examine vaccination policies in schools. Resistance proceeded during the mid-1900s and in 1977 a nationwide Childhood Immunization Initiative was developed with the goal of increasing vaccination rates among children to 90% by 1979. During the two-year period of observation, the initiative reviewed the immunization records of more than 28 million children and vaccinated children who had not received the recommended vaccines.[21]

In 1922, the constitutionality of childhood vaccination was examined in the Supreme Court case Zucht v. King. The court decided that a school could deny admission to children who failed to provide a certification of vaccination for the protection of the public health.[21] In 1987, a measles epidemic occurred in Maricopa County, Arizona and another court case, Maricopa County Health Department vs. Harmon, examined the arguments of an individual's right to education over the states need to protect against the spread of disease. The court decided that it is prudent to take action to combat the spread of disease by denying un-vaccinated children a place in school until the risk for the spread of measles had passed.[21]

Schools in the United States require an updated immunization record for all incoming and returning students. While all states require an immunization record, this does not mean that all students must get vaccinated. Exemptions are determined at a state level. In the United States, exemptions take one of three forms: medical, in which a vaccine is contraindicated due to a component ingredient allergy or existing medical condition; religious; and personal philosophical opposition. As of 2019, 45 states allow religious exemptions, with some states requiring proof of religious membership. Until 2019, only Mississippi, West Virginia and California did not permit religious exemptions.[22] However, the 2019 measles outbreak led to the repeal of religious exemptions in the state of New York and for the MMR vaccination in the state of Washington. Prior to 2019, 18 states allowed personal or philosophical opposition to vaccination, but the measles outbreak also led to the repeal of these exemptions in a number of states.[6] Research studies have found a correlation between the rise of vaccine-preventable diseases and non-medical exemptions from school vaccination requirements.[23][24]

Mandatory vaccinations for attending public schools have received criticism. Parents say that vaccine mandates in order to attend public schools prevent one's right to choose, especially if the vaccinations could be harmful.[25] Some people believe that being forced to get a vaccination could cause trauma, and may lead to not seeking out medical care/attention ever again.[26] In the constitutional law, some states have the liberty to withdraw to public health regulations, which includes mandatory vaccination laws that threaten fines. Certain laws are being looked at for immunization requirements, and are trying to be changed, but cannot succeed due to legal challenges.[27] After California removed non-medical exemptions for school entrance, lawsuits were filed arguing for the right for children to attend school regardless of their vaccination history, and to suspend the bill’s implementation altogether. [27] However, all such lawsuits ultimately failed.[28]

Health care workers

Most states have some kind of requirement in place that at least some kinds of health care workers receive certain vaccinations intended to protect their patients from having communicable diseases passed to them through the health care workers. The vaccines at issue often include those for influenza, measles, hepatitis B for healthcare workers likely to be exposed to human blood, and rubella for healthcare workers likely to be in contact with pregnant women.

Military personnel

Immunizations are often compulsory for military enlistment in the U.S.[29] The United States has a very complex history with compulsory vaccination, particularly in enforcing compulsory vaccinations both domestically and abroad to protect American soldiers during times of war. There are hundreds of thousands of examples of soldier deaths that were not the result of combat wounds, but were instead from disease.[30] During the American Revolutionary War, General George Washington required American soldiers to undergo variolation for smallpox out of concern that the British, who had long engaged in that practice in their own military, would be able to use smallpox as a weapon against the Continental Army. Among wars with high death tolls from disease is the Civil War where an estimated 620,000 soldiers died from disease. American soldiers in other countries have spread diseases that ultimately disrupted entire societies and healthcare systems with famine and poverty.[31]

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War began in April 1898 and ended in August 1898. During this time the United States gained control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines from Spain. As a military police power and as colonizers the United States took a very hands-on approach in administering healthcare particularly vaccinations to natives during the invasion and conquest of these countries.[30] Although the Spanish–American War occurred during the era of "bacteriological revolution" where knowledge of disease was bolstered by germ theory, more than half of the soldier casualties in this war were from disease.[30] Unknowingly, American soldiers acted as agents of disease transmission, fostering bacteria in their haphazardly made camps. These soldiers invaded Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines and connected parts of these countries that had never before been connected due to the countries sparse nature thereby beginning epidemics.[30] The mobility of American soldiers around these countries encouraged a newfound mobility of disease that quickly infected natives.

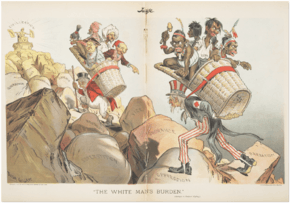

Military personnel used Rudyard's Kipling's poem "The White Man's Burden" to explain their imperialistic actions in Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico and the need for the United States to help the "dark-skinned Barbarians"[30] reach modern sanitary standards. American actions abroad before, during, and after the war emphasized a need for proper sanitation habits especially on behalf of the natives. Natives who refuse to oblige with American health standards and procedures risked fines or imprisonment.[30] One penalty in Puerto Rico included a $10 fine for a failure to vaccinate and an additional $5 fine for any day you continue to be unvaccinated, refusal to pay resulted in ten or more days of imprisonment. If entire villages refused the army's current sanitation policy at any given time they risked being burnt to the ground in order to preserve the health and safety of soldiers from endemic smallpox and yellow fever.[30] Vaccines were forcibly administered to the Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Filipinos. Military personnel in Puerto Rico provided Public Health services that culminated in military orders that mandated vaccinations for children before they were six months old, as well as a general vaccination order.[30] By the end of 1899 in Puerto Rico alone the U.S. military and other hired native vaccinators called practicantes, vaccinated an estimated 860,000 natives in a five-month period. This period began the United States' movement toward an expansion of medical practices that included "tropical medicine" in an attempt to protect the lives of soldiers abroad.[30]

Adverse event reporting

There are several programs for monitoring the safety of vaccines in the United States. Chief among these is the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), which is co-managed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). VAERS is a postmarketing surveillance program, collecting information about adverse events (possible harmful side effects) that occur after administration of vaccines to ascertain whether the risk–benefit ratio is high enough to justify continued use of any particular vaccine. In addition to VAERS, the Vaccine Safety Datalink, and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network are tools by which the CDC and FDA measure vaccine safety.[32]

Vaccine injury compensation

The National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP or NVICP) was established pursuant to the 1986 National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA), passed by the United States Congress in response to a threat to the vaccine supply due to a 1980s scare over the DPT vaccine. Despite the belief of most public health officials that claims of side effects were unfounded, large jury awards had been given to some plaintiffs, most DPT vaccine makers had ceased production, and officials feared the loss of herd immunity.[33] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services set up the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) in 1988 to compensate individuals and families of individuals injured by covered childhood vaccines.[34]

The Office of Special Masters of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, popularly known as "vaccine court", administers a no-fault system for litigating vaccine injury claims. These claims against vaccine manufacturers cannot normally be filed in state or federal civil courts, but instead must be heard in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, sitting without a jury.[33] Compensation covers medical and legal expenses, loss of future earning capacity, and up to $250,000 for pain and suffering; a death benefit of up to $250,000 is available. If certain minimal requirements are met, legal expenses are compensated even for unsuccessful claims.[35] Since 1988, the program has been funded by an excise tax of 75 cents on every purchased dose of covered vaccine. To win an award, a claimant must have experienced an injury that is named as a vaccine injury in a table included in the law within the required time period or show a causal connection. The burden of proof is the civil law preponderance-of-the-evidence standard, in other words a showing that causation was more likely than not. Denied claims can be pursued in civil courts, though this is rare.[33]

The VICP covers all vaccines listed on the Vaccine Injury Table maintained by the Secretary of Health and Human Services; in 2007 the list included vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), measles, mumps, rubella (German measles), polio, hepatitis B, varicella (chicken pox), Haemophilus influenzae type b, rotavirus, and pneumonia.[36] From 1988 until 8 January 2008, 5,263 claims relating to autism, and 2,865 non-autism claims, were made to the VICP. 925 of these claims, one autism-related (see previous rulings), were compensated, with 1,158 non-autism and 350 autism claims dismissed; awards (including attorney's fees) totaled $847 million.[37] As of October 2019, $4.2 Billion in compensation (not including attorneys fees and costs) has been awarded over the forty-three year history of the program.[38]

References

- "Immunization Schedules". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- 21 CFR 312.23(a)(8).

- Abramson, Brian Dean (2019). "2". Vaccine, Vaccination, and Immunization Law. Bloomberg Law. p. 11.

- Abramson, Brian Dean (2019). "5". Vaccine, Vaccination, and Immunization Law. Bloomberg Law. p. 13.

- "Measles Outbreak: N.Y. Eliminates Religious Exemptions for Vaccinations". New York Times. June 13, 2019. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019.

- "States with Religious and Philosophical Exemptions from School Immunization Requirements". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Ciolli A (September 2008). "Mandatory school vaccinations: the role of tort law". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 81 (3): 129–37. PMC 2553651. PMID 18827888.

- May T, Silverman RD (March 2003). "'Clustering of exemptions' as a collective action threat to herd immunity". Vaccine. 21 (11–12): 1048–51. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00627-8. hdl:1805/6156. PMID 12559778.

- Faiola, Anthony; Srinivas, Preethi; Karanam, Yamini; Chartash, David; Doebbeling, Bradley (2014). "Viz Com". Proceedings of the extended abstracts of the 32nd annual ACM conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI EA '14. pp. 1705–1710. doi:10.1145/2559206.2581332. hdl:1805/6156. ISBN 978-1-4503-2474-8.

- Diekema DS (May 2005). "Responding to parental refusals of immunization of children". Pediatrics. 115 (5): 1428–31. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0316. PMID 15867060.

- "FIGURE 1: Recommended immunization schedule for persons aged 0 through 18 years" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- "Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule — United States, 2014" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- "Report of Medical Examination and Vaccination Record". USCIS.

- Jordan M (2008-10-01). "Gardasil requirement for immigrants stirs backlash". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- "HPV vaccine no longer required for green cards". nbcnews.com. 17 November 2009.

- "Ethical Issues and Vaccines | History of Vaccines". www.historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- "Vaccine Information Statement | Facts About VISs | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- McAllister-Grum K (2017). "Pigments and Vaccines: Evaluating the Constitutionality of Targeting Melanin Groups for Mandatory Vaccination". The Journal of Legal Medicine. 37 (1–2): 217–247. doi:10.1080/01947648.2017.1303288. PMID 28910223.

- Hodge JG, Gostin LO (2001). "School vaccination requirements: historical, social, and legal perspectives". Kentucky Law Journal. 90 (4): 831–90. PMID 15868682.

- Tolley, Kim (May 2019). "School Vaccination Wars". History of Education Quarterly. 59 (2): 161–194. doi:10.1017/heq.2019.3.

- Malone, Kevin M; Hinman, Alan R (2003). "The Public Health Imperative and Individual Rights". Law in Public Health Practice: 262–84.

- Horowitz, Julia (30 June 2015). "California governor signs strict school vaccine legislation". Associated Press. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Goldstein, N. D.; Purtle, J.; Suder, J.S. (November 18, 2019). "Association of Vaccine-Preventable Disease Incidence With Proposed State Vaccine Exemption Legislation". JAMA Pediatrics. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4365.

- Wang, Eileen; Clymer, Jessica; Davis-Hayes, Cecilia; Buttenheim, Alison (2014). "Nonmedical Exemptions From School Immunization Requirements: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Public Health. 104: 62–84. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302190.

- "Is it bad policy?". NCSL. 17 January 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Cantor, Julie D. “Mandatory Measles Vaccination in New York City - Reflections on a Bold Experiment.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 381, no. 2, July 2019, pp. 101–103. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1056/NEJMp1905941

- Barraza, Leila, et al. “The Latest in Vaccine Policies: Selected Issues in School Vaccinations, Healthcare Worker Vaccinations, and Pharmacist Vaccination Authority Laws.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 45, Mar. 2017, pp. 16–19. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1177/1073110517703307.

- "California's mandatory-vaccination law survives court test". SFChronicle.com. July 4, 2018.

- United States Department of Defense. "MilVax homepage". Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- Willrich, Michael (2010). Pox: An American History. New York, New York: Penguin Group. pp. 117–165. ISBN 9781101476222.

- "Vaccine Scheduler | ECDC". vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Vaccine Safety Monitoring at CDC, retrieved 2015-03-11.

- Sugarman SD (2007). "Cases in vaccine court – legal battles over vaccines and autism". N Engl J Med. 357 (13): 1275–77. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078168. PMID 17898095.

- Edlich RF; Olson DM; Olson BM; et al. (2007). "Update on the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program". J Emerg Med. 33 (2): 199–211. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.01.001. PMID 17692778.

- "Filing a claim with the VICP". Health Resources and Services Administration. Retrieved 2013-08-19.

- "Vaccine Injury Table". Health Resources and Services Administration. 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- "National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program statistics reports". Health Resources and Services Administration. 2008-01-08. Archived from the original on September 23, 2001. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- "National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program Monthly Statistics Report". Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. October 2019.