Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (also known by the abbreviations UPPP and UP3) is a surgical procedure or sleep surgery used to remove tissue and/or remodel tissue in the throat. This could be because of sleep issues. Tissues which may typically be removed include:

| Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. | |

|---|---|

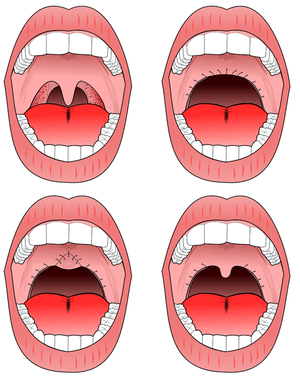

View of the throat 8 years following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 27.6, 27.7, 29 |

Tissues which may typically be remodeled include:

- The uvula (see uvulotomy)

- The soft palate

- The pharynx

How UPPP is executed

UPPP involves removal of the tonsils, the posterior surface of the soft palate, and the uvula. The uvula is then folded toward the soft palate and sutured together as demonstrated in the figures. In the US, UPPP is the most commonly performed procedure for obstructive sleep apnea with approximately 33,000 procedures performed per year. The surgery is more successful in patients who are not obese, and there is a limited role in morbidly obese (>40 kg/m2) individuals.

Procedural details

Standard UPPP procedure

UPPP is typically administered to patients with obstructive sleep apnea in isolation. It is administered as a stand-alone procedure in the hope that the tissue which obstructs the patient's airway is localized in the back of the throat. The rationale is that, by removing the tissue, the patient's airway will be wider and breathing will become easier.

The Role of UPPP in the "Stanford Protocol" operation

UPPP is also offered to sleep apnea patients who opt for a more comprehensive surgical procedure known as the "Stanford Protocol", first attempted by Doctors Nelson Powell and Robert Riley of Stanford University. The Stanford Protocol consists of two phases. The first involves surgery of the soft tissue (tonsillectomy, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty) and the second involves skeletal surgeries (maxillomandibular advancement). First, Phase 1 or soft tissue surgery is performed and after re-testing with a new sleep study, if there is residual sleep apnea, then Phase 2 surgery would consist of jaw surgery. The goal is to improve the airway and thereby treat (or possibly cure) sleep apnea. It has been found that obstructive sleep apnea usually involves multiple sites where tissue obstructs the airway; the base of the tongue is often involved. The Protocol successively addresses these multiple sites of obstruction. Note that genioglossus advancement can be performed either during Phase 1 or Phase 2 surgeries.

Phase 2 involves maxillomandibular advancement, a surgery which moves the jaw top (maxilla) and bottom (mandible) forward. The tongue muscle is anchored to the chin, and translation of the mandible forward pulls the tongue forward as well. If the procedure achieves the desired results, when the patient sleeps and the tongue relaxes, it will no longer be able to block the airway. Success is much better for Phase 2 than for Phase 1 - approximately 90 percent benefit from the second phase, and the success of the Stanford Protocol Operation therefore is due in large part to this second phase.

There is debate among surgeons as to the role of Phase 1 surgery. In 2002, an Atlanta-based surgical team, led by Dr. Jeffrey Prinsell, published results which have approximated those of the Stanford team when UPPP was not included in their mix of surgeries.

Success

The effectiveness of UPPP in isolation

When UPPP has been administered in isolation, the results are variable. As explained above, sleep apnea is often caused by multiple co-existing obstructions at various locations of the airway such as the nasal cavity, and particularly the base of the tongue. The contributing factors in the variability of success include the pre-surgical size of the tonsils, palate, uvula and tongue base. Also, patients who are morbidly obese (body mass index >40 kg/m2) are significantly less likely to have success from this surgery.

Effectiveness of "The Stanford Protocol" operation

Over one thousand people have undergone The Stanford Protocol operation and received follow-up sleep study testing. 60 to 70 percent of patients have been entirely cured.[1] In approximately ninety percent of patients, a significant improvement can be expected.

Multilevel approach

In the recent years, many surgeons have tried to address the multiple levels of obstruction by performing multiple procedures on the same surgical day, called the "multi-level approach". Typical surgeries in a multi-level approach may include:

Nasal-level surgeries

- turbinoplasty, septoplasty, septorhinoplasty

Soft palate-level surgeries

- uvulectomy, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, tonsillectomy

Hypopharyngeal-level surgeries

- hyoid suspension

- tongue suspension

- tongue base reduction

- genioglossus advancement

UPPP with tonsillectomy improves postoperative results of obstructive sleep anpea depending on tonsil size. The success rate increases with increasing tonsil size.[2] This approach improves postoperative results in well-selected patients.[3]

Laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

Risks

One of the risks is that by cutting the tissues, excess scar tissue can "tighten" the airway and make it even smaller than it was before UPPP. Some individuals who have undergone UPPP as a stand-alone procedure have written on internet forums that they experienced a worsening of their breathing following UPPP.[4][5][6][7] Others have spoken of severe acid reflux.[8]

After surgery, complications may include these:

- Sleepiness and sleep apnea related to post-surgery medication

- Swelling, infection and bleeding

- A sore throat and/or difficulty swallowing

- Drainage of secretions into the nose and a nasal quality to the voice. English language speech does not seem to be affected by this surgery.

- Narrowing of the airway in the nose and throat (hence constricting breathing) snoring and even iatrogenically caused sleep apnea.

- Patients who have had the uvula removed will become unable to correctly pronounce uvular consonants, found in French, German, Hebrew, and others.

- Long term complications with pain, feeling sick and lesser sleep quality than before the LAUP.

In 2008, Dr. Labra, et al., from Mexico, published a variation of UP3, by adding a uvulopalatal flap, in order to avoid such complications, with a good rate of success.[9]

References

- Li, Kasey K.; Powell, Nelson B.; Riley, Robert W.; Troell, Robert J.; Guilleminault, Christian (2000). "Long-Term Results of Maxillomandibular Advancement Surgery". Sleep and Breathing. 4 (3): 137–140. doi:10.1007/s11325-000-0137-3. PMID 11868133.

- Tschopp, Samuel; Tschopp, Kurt (2019). "Tonsil size and outcome of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty with tonsillectomy in obstructive sleep apnea". The Laryngoscope. 0. doi:10.1002/lary.27899. ISSN 1531-4995. PMID 30848478.

- Handler, Ethan; Hamans, Evert; Goldberg, Andrew N.; Mickelson, Samuel (2014). "Tongue suspension". The Laryngoscope. 124 (1): 329–36. doi:10.1002/lary.24187. PMID 23729234.

- http://www.sleepnet.com/noncpap16/messages/702.html%5B%5D%5B%5D

- http://www.sleepnet.com/noncpap12/messages/172.html%5B%5D%5B%5D

- http://www.sleepnet.com/noncpap18/messages/552.html%5B%5D%5B%5D

- http://www.sleepnet.com/noncpap19/messages/549.html%5B%5D%5B%5D

- http://www.sleepnet.com/noncpap20/messages/286.html%5B%5D%5B%5D

- Labra, A; Huerta-Delgado, A. D.; Gutierrez-Sanchez, C; Cordero-Chacon, S. A.; Basurto-Madero, P (2008). "Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and uvulopalatal flap for the treatment of snoring: Technique to avoid complications". Journal of Otolaryngology. 37 (2): 256–9. PMID 19128622.

Further reading

- WebMDHealth. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for snoring Retrieved August 26, 2005.

- Royal College of Surgeons Audit Symposium March 8th 2002 Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- University of Maryland Medical Center Patient Education - UPPP Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- The Vancouver Sleep and Breathing Centre May 30, 2006 Risks associated with LAUP surgeries