Uterine microbiome

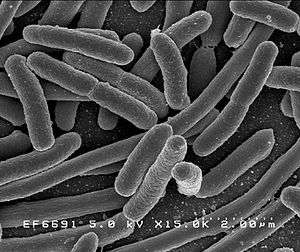

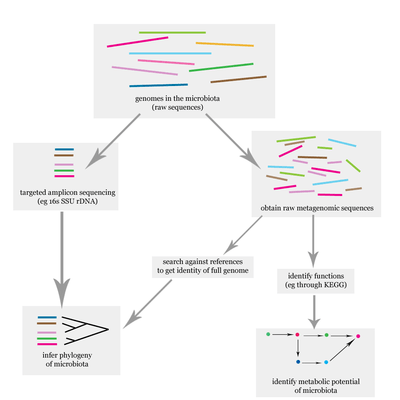

The uterine microbiome is the commensal, nonpathogenic, bacteria, viruses, yeasts/fungi present in a healthy uterus, amniotic fluid and endometrium and the specific environment which they inhabit. It has been only recently confirmed that the uterus and its tissues are not sterile.[1] Due to improved 16S rRNA gene sequencing techniques, detection of bacteria that are present in low numbers is possible.[2] Using this procedure that allows the detection of bacteria that cannot be cultured outside the body, studies of microbiota present in the uterus are expected to increase.[3]

Uterine microbiome and fertility

Evidence shows that the presence of uterine 16S rRNA is not only the result of sampling or analysis errors and deserves to be acknowledged.Concept of the sterile endometrium, and the uterine compartment in general, is outworn, although the true core uterine microbiome still needs to be assessed. Functional studies are needed to elucidate the physiological importance of the microbiome in fertility. The challenge of studying reproductive immunology and the microbiota involved is that research on all of the different aspects is still in its infancy; microbiome, immunity, endocrinology in pregnancy, and placental and fetal development need to be studied together to obtain a more comprehensive overview. [4]

Characteristics

Bacteria, viruses and one genus of yeasts are a normal part of the uterus before and during pregnancy.[5] The uterus has been found to possess its own characteristic microbiome that differs significantly from the vaginal microbiome. Despite its close spatial connection with the vagina, the microbiome of the uterus more closely resembles the commensal bacteria found in the oral cavity. In addition, the immune system is able to differentiate between those bacteria normally found in the uterus and those that are pathogenic. Hormonal changes have an effect on the microbiota of the uterus.[6]

Taxa

Commensals

The organisms listed below have been identified as commensals in the healthy uterus. Some also have the potential for growing to the point of causing disease:

Organism Commensal Transient Potential

pathogenReferences Escherichia coli x x [6] Escherichia spp. x x [6] Ureaplasma parvum x x [6] Fusobacterium nucleatum x [7] Prevotella tannerae x [5] Bacteroides spp. x [5] Streptomyces avermitilis x [6] Mycoplasma spp. x x [5] Neisseria lactamica x [6] Neisseria polysaccharea x [6] Epstein-Barr virus x x [5] Respiratory-Syncytial virus x x [5] Adenovirus x x [5] Candida spp. x x [5]

Pathogens

Other taxa can be present, without causing disease or an immune response. Their presence is associated with negative birth outcomes.[5][6]

Pathogenic Organism Increased risk of References Ureaplasma urealyticum Premature, preterm rupture of membranes

Preterm labor

cesarean section

Placental inflammation

Congenital pneumonia

bacteremia

meningitis

fetal lung injury

death of infant[5][8][9] Haemophilus influenzae Premature, preterm rupture of membranes

preterm labor

preterm birth[5] Ureaplasma parvum [5] Fusobacterium nucleatum [5] Prevotella tannerae [5] Bacteroides spp. Streptomyces avermitilis [5] Mycoplasma hominis Congenital pneumonia

bacteremia

meningitis

<pelvic inflammatory disease

postpartum or postabortal fever[5][8] Neisseria lactamica [5] Neisseria polysaccharea [5] Epstein-Barr virus [5] Respiratory-Syncytial virus [5] Adenovirus [5] Candida spp. [5]

Clinical significance

Prophylactic antibiotics have been injected into the uterus to treat infertility. This has been done before the transfer of embryos with the intent to improve implantation rates. No association exists between successful implantation and antibiotic treatment.[10] Infertility treatments often progress to the point where a microbiological analysis of the uterine microbiota is performed. Preterm birth is associated with certain species of bacteria that are not normally part of the healthy uterine microbiome.[5]

Immune response

The immune response becomes more pronounced when bacteria are found that are not commensal.[5]

History

Investigations into reproductive-associated microbiomes began around 1885 by Theodor Escherich. He wrote that meconium from the newborn was free of bacteria. There was a general consensus at the time and even recently that the uterus was sterile and this was referred to as the sterile womb paradigm. Other investigations used sterile diapers for meconium collection. No bacteria were able to be cultured from the samples. Other studies showed that bacteria were detected and were directly proportional to the time between birth and the passage of meconium.[1]

Research

Investigations into the role of the uterine microbiome in the development of the infant microbiome are ongoing.[1]

See also

References and notes

- Perez-Muñoz, Maria Elisa; Arrieta, Marie-Claire; Ramer-Tait, Amanda E.; Walter, Jens (2017). "A critical assessment of the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome". Microbiome. 5 (1). doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4. ISSN 2049-2618. PMC 5410102.

- Verstraelen, Hans; Vilchez-Vargas, Ramiro; Desimpel, Fabian; Jauregui, Ruy; Vankeirsbilck, Nele; Weyers, Steven; Verhelst, Rita; De Sutter, Petra; Pieper, Dietmar H.; Van De Wiele, Tom (2016). "Characterisation of the human uterine microbiome in non-pregnant women through deep sequencing of the V1-2 region of the 16S rRNA gene". PeerJ. 4: e1602. doi:10.7717/peerj.1602. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4730988. PMID 26823997.

- Wassenaar, T.M.; Panigrahi, P. (2014). "Is a foetus developing in a sterile environment?". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 59 (6): 572–579. doi:10.1111/lam.12334. ISSN 0266-8254. PMID 25273890.

- Moreno, I. and Franasiak, J. (2017). Endometrial microbiota—new player in town. Fertility and Sterility, 108(1), pp.32-39.

- Payne, Matthew S.; Bayatibojakhi, Sara (2014). "Exploring Preterm Birth as a Polymicrobial Disease: An Overview of the Uterine Microbiome". Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 595. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00595. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 4245917. PMID 25505898.

- Yarbrough, V. L.; Winkle, S.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. (2014). "Antimicrobial peptides in the female reproductive tract: a critical component of the mucosal immune barrier with physiological and clinical implications". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (3): 353–377. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu065. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 25547201.

- Prince, Amanda L.; Antony, Kathleen M.; Chu, Derrick M.; Aagaard, Kjersti M. (2014). "The microbiome, parturition, and timing of birth: more questions than answers". Journal of ReproductiveImmunology. 104–105: 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2014.03.006. ISSN 0165-0378. PMC 4157949. PMID 24793619.

- "Ureaplasma Infection: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 17 November 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017 – via eMedicine. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pryhuber, Gloria S. (2015). "Postnatal Infections and Immunology Affecting Chronic Lung Disease of Prematurity". Clinics in Perinatology. 42 (4): 697–718. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2015.08.002. ISSN 0095-5108. PMC 4660246. PMID 26593074.

- Franasiak, Jason M.; Scott, Richard T. (2015). "Reproductive tract microbiome in assisted reproductive technologies". Fertility and Sterility. 104 (6): 1364–1371. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.012. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 26597628.