Triangle of death (Italy)

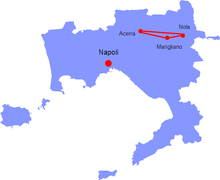

The triangle of death (Italian: Triangolo della morte) is an area in the Province of Naples, Campania, Italy, comprising the municipalities of Acerra, Nola and Marigliano that contains the largest illegal waste dump in Europe due to a waste management crisis.[1][2] The region has recently experienced increasing deaths caused by cancer and other diseases that exceeds the Italian national average. The rise in cancer-related mortality is linked to exposure of pollution from illegal waste disposal by the Camorra criminal organization.[3]

Definition

The term "triangle of death" was first used with regards to the region in a September 2004 scientific publication in the Lancet Oncology.[4][5][6]

An estimated 550,000 people live in this area. The annual death rate per 100,000 inhabitants from liver cancer is close to 34.5 for men and 20.8 for women, as compared to the national average of 14. The death rate for bladder cancer and cancer of the central nervous system is higher than in other European countries, although by a more modest increment. Campania, overall, has a lower-than-average cancer mortality rate than Italy.

The high death rates from cancers pointed towards the presence of illegal and improper hazardous waste disposal by various organized crime groups including the Camorra.[7]

The Lancet Oncology article noted:

Today, the difference between lawful management of waste and illegal manipulation with regard to their compliance with health regulations is very narrow, and the health risks are rising.

— Alfredo Mazza, The Lancet Oncology, vol. 5, September 2004

and

The 5000 illegal or uncontrolled landfill sites in Italy drew particular criticism; Italy has already been warned twice for flouting the Hazardous Waste Directive and the Landfill Directive, and the EU has now referred Italy to the European Court of Justice for further action.

— The Lancet Oncology, vol. 5, September 2004

The report was met with criticism by the National Research Council, dismissing the methods used by Senior and Mazza as biased.[8] Despite this, it sparked the first interest and concern into this matter, and has become the most cited source of evidence throughout the crisis.[8]

Though some media outlets report France[2] and Germany[9] as waste sources the EU remains silent as to the sources of the waste in their criticisms and demands of Italy.

Epidemiological research

In 2007, research[10] conducted by the World Health Organization, Italian Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche and Campania Region collected data on cancer and congenital abnormalities in 196 municipalities covering the period between 1994 and 2002 found abnormally high disease incidence. These abnormal patterns may correlate to areas where there are uncontrolled waste sites. However, this work also highlighted the difficulty in determining causality and in establishing a link between increased death and malformation rates and waste disposal.

After the Senior and Mazza study, several other studies have been conducted to attempt to definitively link elevated cancer rates to waste exposure.[8] A government-made waste-exposure index that classifies areas of the Campania region as high (5 on index) or low (1 on index) risk based on the type of wastes present in surrounding dumping sites, total waste volume greater than 10,000 cubic metres, and the likelihood of releases on water, soil and air was created. Statistically significant excess relative risks were found for several cancer types in the triangle of death, however, methods often struggle to account for lifestyle confounders such as tobacco consumption and occupation which could skew the results.[11]

A US Navy study denied any real ill effects to on-base personnel while however advising their off-base personnel to drink bottled water citing polluted wells. The US Navy report denied any signs of nuclear waste dumping and instead related the traces of uranium to volcanic activity.[12][13]

Illegal toxic waste dumping in Campania

The boss of the Casalesi clan, Gaetano Vassallo, admitted to systematically working for 20 years to bribe local politicians and officials to gain their acquiescence to dumping toxic waste.[14][15] Giorgio Napolitano, President of Italian Republic, said in June 2008:[16][17]

It is certain, not only to citizens but to the government as well, that the systematic transfer of toxic waste from industries in Northern Italy to Campania, was committed by the Camorra

— Giorgio Napolitano, 4 June 2008.

Dangerous pollutants such as dioxins, are found in the area, particularly around Acerra,[18] as well as illegal waste disposal,[19] even in the business district of Montefibre.[20] As early as 1987, a decree of the Ministry of Environment marked Acerra "at high risk of environmental crisis".[21]

High levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were detected both in the soil and in the inhabitants of the region, though no obvious emitters are known.[22] It is hypothesized that industrial slurry originating from Porto Marghera (industrial docklands near Venice) was disguised as compost and spread on fields in the Acerra countryside by the Casalesi clan, often with help from the landowners.[23][24]

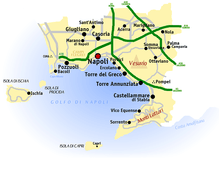

In one case, a company had its assets seized during a 2006 investigation[25] in which it was alleged that the company had illegally disposed of waste from industries in the regions of Veneto and Tuscany in the territories of Bacoli, Giugliano and Qualiano. Approximately one million tonnes of toxic waste are said to have been disposed of, earning €27 million. The company was already the subject of a 2003 investigation.[26] In another case, a tank full of toxic substances was found buried in an illegal dump, in Marigliano.[27][28]

The illegal burning of waste, for example to recover copper from wiring,[29][30] is known to release dioxins into the atmosphere of Earth. Such fires are easily hidden among legitimate incineration resulting from the more general waste disposal problem, and the illegal burning of hazardous materials was particularly noted during 2007 and 2008. Between January and March 2007, 30,000 kilograms of waste were burned on agricultural land, with a revenue of more than €118,000.[29] The presence of fires in the north area of Naples led author Roberto Saviano to use "Land of pyres" (terra dei fuochi) as chapter titles in his book Gomorrah.[31]

Hazardous industrial waste disposal may happen in lawful landfills, too. In 2000, a Parliamentary Commission enquiry about waste[32] discovered some 800,000 tonnes of mud in Pianura landfill, coming from ACNA of Cengio[33][34] in Naples, and the Italian Procura della Repubblica found (through telephone wiretappings) some irregularities in the waste disposal into the landfill of Villaricca, managed by FIBA (a company of the Impregilo group).[35]

Opposition to landfills

In 2008 the waste commissioner Guido Bertolaso, (the head of the civil protection department), planned to open a landfill but this was opposed by Chiaiano's residents,[36] because of mistrust of the governing institutions and the awareness of the population of the rise in cancer death rate.

There was similar resistance in Pianosa to reopening a closed landfill proposed by government commissioner Giovanni De Gennaro. In 2007 and 2008 some of the protests turned violent,[37] particularly in Naples and the suburbs of Quarto and Pozzuoli. It is alleged that there was collusion between local political interests and organised crime over building interests.[38][39]

The incinerator of Acerra was also seen as potential source of pollution and stirred conflict and debate in the local area.[40] In 2009, the Acerra incineration facility was completed at a cost of over €350 million. The incinerator burns 600,000 tons of waste per year to produce refuse-derived fuel. The energy produced from the facility is enough to power 200,000 households per year.[41]

Causes

The triangle of death results partially from the Government failure regarding waste management. For a long time the Government has been trying to mandate recycling and waste management programs, but the results have not been efficient. The first issue coincides with decentralization in the governmental structure, which leads to implementation problems. In fact, local executive branches are supposed to supply waste management services, but since the central government can not exert full control over the different regions, local administration fail to follow the policy procedures.[4] As a result of the low supply and quality of the public waste management services, black markets have arisen to get rid of the excess waste. These illegal operations are controlled by the Mafia, who does not follow the right recycling and waste disposal techniques and thus produces negative externalities such as health hazards. In particular, harmful materials such as lead or acid batteries need special caution, which is not provided by black markets.[42]

A second cause is Market Failure, which derives from the fact that waste management is a public good and from information asymmetry between the government and the population. Waste management is a non-rivalrous and non-excludable good, and thus can be identified as a Public Good with consumption Externalities. The externalities produced by environmentally friendly waste management, such as recycling practices, are positive and therefore provide marginal social benefits that are higher than the marginal private benefits. As a result, waste management tends to be undersupplied. Moreover, the population has not been well educated about the positive externalities produced by recycling and thus Italian households have shown low rates of separate collection of waste materials, with the lowest percentages in the South.[43] Since there is not cooperation by the population, waste management implementation is more difficult to fully achieve at an efficient level.[44]

Pollution and agriculture exports

The agro-economy of the region has been adversely affected by this dumping. In the region, over 12,000 cattle, river buffaloes and sheep had been culled before 2006.[45] High levels of mortality and abnormal foetuses were also recorded in farms in Acerra linked to elevated levels of dioxin.[45] Local studies have shown higher than permissible levels of lead in vegetables grown in the area.[46] The government blames the Mafia's illegal garbage disposal racket.[46] In March 2008,[47] dioxin were found in buffalo milk from farms in Caserta. Countries such as South Korea and Japan identified this pollution and subsequently banned imports of buffalo milk from the region. While only 2.8% of farms in Campania were affected,[48] the sale of dairy products from Campania collapsed in both domestic and global markets.[49][50][51]

Literature and film

The issue was raised by Roberto Saviano in his book Gomorrah and in the film of the same name. It was also the subject of a documentary by Esmeralda Calabria and Andrea D'Ambrosio entitled Biùtiful cauntri.

See also

- Camorra

- Ecomafia

- Environmental racism in Europe

- Naples waste management issue

- Gomorrah (book)

- Gomorrah (film)

- Biùtiful cauntri

- Radioactive waste dumping by the 'Ndrangheta

Notes

- "Italy discovers biggest illegal waste dump in Europe". Euronews. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Day, Michael (17 June 2015). "Europe's largest illegal toxic dumping site discovered in southern Italy – an area with cancer rates 80% higher than national average". The Independent. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Winfield, Nicole (2 January 2016). "Italy confirms higher cancer, death rates from mob's dumping of toxic waste". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Senior, Kathryn; Mazza, Alfredo (September 2004). "Italian "Triangle of death" linked to waste crisis". The Lancet Oncology. 5 (9): 525–527. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01561-X. ISSN 1470-2045. PMID 15384216.

- "Il triangolo della morte". rassegna.it. March 1, 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- "Discariche piene di rifiuti tossici quello è il triangolo della morte". la Repubblica. 2004-08-31. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- "Bolle false e finti trattamenti così camuffiamo i veleni". la Repubblica. 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- Cantoni, Roberto (2016). "The waste crisis in Campania, South Italy: a historical perspective on an epidemiological controversy" (PDF). Endeavour. 40 (2): 102–113. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2016.03.003. PMID 27180606.

- Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey. "The Mob Is Secretly Dumping Nuclear Waste Across Italy and Africa". gizmodo.com.

- Look at review Archived 2006-12-31 at the Wayback Machine into the review Trattamento dei rifiuti in Campania: impatto sulla salute umana dell Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche e Regione Campania.

- Martuzzi, M.; Mitis, F.; Bianchi, F.; Minichili, F.; Comba, P.; Fazzo, L. (2009). "Cancer mortality and congenital anomalies in a region of Italy with intense environmental pressure due to waste" (PDF). Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 66 (11): 725–732. doi:10.1136/oem.2008.044115. PMID 19416805.

- "Naples base seeks to assuage fears amid new reports of toxic dumping". stripes.com.

- "Italian prosecutors draw on Navy study in probe of toxic dumping". stripes.com.

- "Così ho avvelenato Napoli". l'Espresso. 2008-09-11. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- "Inchiesta sui veleni a Napoli perquisiti l'Espresso e due reporter". la Repubblica. 2009-09-12. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- "Napolitano: "Rifiuti tossici arrivati in gran parte dal nord"". la Repubblica. 2008-06-04. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- "Rifiuti, l'allarme di Napolitano: "Quelli tossici provengono dal Nord"". la Stampa. 2008-06-04. Archived from the original on 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ambienti, ed. (2007-09-18). "Diossina ad Acerra, analisi fai da te". il Manifesto. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Morire di diossina nel paese dei rifiuti Ricerca dell'Oms Qui il cancro uccide trenta volte di piu". la Stampa. 2007-05-07. Archived from the original on 2009-02-16. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- Roberto Saviano (2004-08-27). "Acerra, polmone di cemento". Archived from the original on 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- D.C.d.M. 26-02-1987.

- "Diossina, la Lilt cerca fondi per le analisi dei cittadini di Acerra, Nola e Marigliano". it:Corriere del Mezzogiorno. 2008-03-14. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- "Dal nord rifiuti industriali in provincia di Caserta". caffenews. Reuters. 2008-02-25. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- "Campania, scoperto traffico illecito dei rifiuti. L'attività di smaltimento gestita dai Casalesi". Ecostiera. 2008-02-25. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- "Rifiuti, sequestro al gruppo Pellini". il Nolano. 2008-09-23. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Complicità ed emergenza rifiuti dietro il traffico illecito scoperto in Campania". VAS Campania. 2006-01-24. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Striscia la notizia: i veleni di Marigliano". Marigliano. 2008-02-27. Archived from the original on 2009-02-15. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- Look at video by Striscia la notizia (italian TV information)

- "Rifiuti, i veleni tra i campi verdi di Caivano, Afragola e Casoria". Ecostiera]. 2008-10-25. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Afragola, scoperti 50 quintali di veleni vicino al cimitero. È allarme diossina per i roghi". Napolinord]. 2008-09-14. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- Peppe Ruggiero (2006-09-29). "La terra dei fuochi a nord di Napoli". Nazione indiana. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- "Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sul ciclo dei rifiuti e sulle attività illecite ad esso connesse".

- "Anche i fanghi dell'Acna di Cengio tra i veleni sepolti sotto quella collina". la Repubblica. 2008-01-22. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- "Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sul ciclo dei rifiuti e sulle attività illecite ad esso connesse".

- "La discarica è piena di liquido se sale sarà come un Vajont". la Repubblica. 2008-05-29. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- "Noi non siamo N.I.M.B.Y." chiaiaNodiscarica. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- "Pianura, scontri alla discarica assaltata anche un'ambulanza". la Repubblica. 2008-01-05. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- "Rifiuti, per gli scontri a Pianura oltre trenta arresti a Napoli". la Repubblica. 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ""Arrivano i Carabinieri". Così Nugnes avvertiva i rivoltosi". la Repubblica. 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- "Protesta contro i rifiuti ad Acerra continua il presidio alla stazione". la Repubblica. 2004-09-11. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- EJOLT. "Urban waste incinerator of Acerra, Italy - EJAtlas". Environmental Justice Atlas.

- Sancilio, Cosmo (1995-09-01). "COBAT: collection and recycling spent lead/acid batteries in Italy". Journal of Power Sources. 57 (1–2): 75–80. Bibcode:1995JPS....57...75S. doi:10.1016/0378-7753(95)02246-5. ISSN 0378-7753.

- Fiorillo, Damiano (2010–2013). "Household waste recycling: national survey evidence from Italy" (PDF). Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 56 (8): 1125–1151. doi:10.1080/09640568.2012.709180. ISSN 0964-0568.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Weimer, David L.; Vining, Aidan R. (2017). Policy Analysis Concepts and Practice. New York: Routledge. pp. 74–112, 149–181. ISBN 978-1-138-21651-8.

- Perucatti, A.; Di Meo, G.P.; Albarella, S.; Ciotola, F.; Incarnato, D.; Jambrenghi, A.C.; Peretti, V.; Vonghia, G.; Iannuzzi, L. (2006). "Increased frequencies of both chromosome abnormalities and SCEs in two sheep flocks exposed to high dioxin levels during pasturage". Mutagenesis. 21 (1): 67–57. doi:10.1093/mutage/gei076. PMID 16434450.

- "Mafia toxic waste dumping poisons Italy farmlands". The Hindu. Associated Press. 20 December 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Mozzarella, limitate positività alla diossina. Il Governo dopo l'alt di Tokyo: no a psicoosi". Corriere della sera. 2008-03-26. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- Consorzio di tutela del formaggio mozzarella di bufala campana DOP (2008-04-20). "Comunicato stampa". Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- "Mandara: Mozzarella sana, ma vendite in calo". Il Denaro. 2008-01-23. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- "I prodotti tipici non si vendono più, la Cia: Rischio tracollo". Il Denaro. 2008-01-15. Archived from the original on 2008-05-04. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- "La spesa al tempo dei rifiuti "Prodotti locali? No, grazie"". La Repubblica-Napoli. 2008-01-16. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

Bibliography

- (in English) Kathryn Senior and Alfredo Mazza, Italian “Triangle of death” linked to waste crisis, The Lancet Oncology, Volume 5, Issue 9, September 2004, Pages 525–527.

- (in Italian) Translation by The Lancet Oncology from the site of Centro Nazionale di Epidemiologia, Sorveglianza e Promozione della Salute

- (in English) Fabrizio Bianchi et al., Italian “Triangle of death”, The Lancet Oncology, Volume 12, Issue 5, December 2004, Page 710.

- (in Italian) Trattamento dei rifiuti in Campania: impatto sulla salute umana, report by World Health Organization, Italian Health Institute, it:Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche e Regione Campania (Italia).

In television

- Report: Terra bruciata, TV 9-3-2008, and how finished this story in: Come è andata a finire?.

- Repubblica Radio TV: Morire di diossina in Campania, del 28-12-2007: , ,

- La 7: Il cancro di Napoli, del 12-12-2007; Allarme cibo avvelenato, Exit del 18-12-2007; Il posto dei rifiuti, del 22-09-2007

- Tg1: interview to Roberto Saviano at 3-1-2008 (evening ediction at 8:00 p.m.)

- Sat 2000: interview to dott. Antonio Marfella, oncologist at "Formato famiglia, 20-12-2007

External links

- La Terra dei fuochi, website showing claims on illegal waste disposal in Campania

- La Terra dei fuochi, website on "triangle of poisons" Giugliano-Qualiano-Villaricca