Transpyloric plane

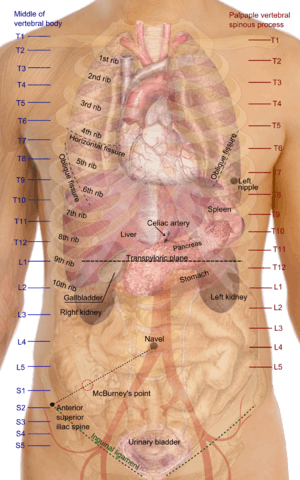

The transpyloric plane, also known as Addison's plane, is an imaginary horizontal plane, located halfway between the suprasternal notch of the manubrium and the upper border of the symphysis pubis at the level of the first lumbar vertebrae, L1. It lies roughly a hand's breadth beneath the xiphisternum[1] or midway between the xiphisternum and the umbilicus.[2] The plane in most cases cuts through the pylorus of the stomach, the tips of the ninth costal cartilages and the lower border of the first lumbar vertebra.[2]

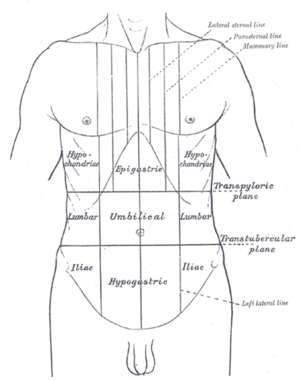

| Transpyloric plane | |

|---|---|

Surface lines of the front of the thorax and abdomen. (Transpyloric is top horizontal line.) | |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | planum transpyloricum |

| TA | A01.2.00.007 |

| FMA | 14608 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

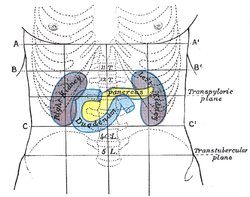

Structures crossed

The transpyloric plane is clinically notable because it passes through several important abdominal structures. It also divides the supracolic and infracolic compartments, with the liver, spleen and gastric fundus above it and the small intestine and colon below it.[2]

Lumbar vertebra and spinal cord

The first lumbar vertebra lies at the level of the transpyloric plane.[3] Despite the conus medullaris, the end of the spinal cord, being understood to terminate at the level of the transpyloric plane, there is significant variability. Up to 40% of people have spinal cords ending below the transpyloric plane.[2][4]

Stomach

The transpyloric plane passes through the pylorus of the stomach, despite it being suspended by the lesser and greater omentum and being relatively mobile.[2][5]

Duodenum

The horizontal part of the duodenum slopes upwards to the left of the vertical midline, following which the vertical ascending part of the duodenum reaches the transpyloric plane.[6] It ends in the duodenojejunal junction, which lies approximately 2.5 cm to the left of the midline and just below the transpyloric plane.[1]

Pancreas

The neck of pancreas lies on the transpyloric plane, whilst the body and tail are to the left and above it.[3]

Gallbladder

The fundus of the gallbladder projects from the liver’s inferior border at the intersection of the transpyloric plane and the right lateral midline.[7]

Kidneys

Despite the right kidney lying 1 cm lower than the left (right just below and the left just above the plane),[2] to be practical, the surface markings are taken the same way. The hilum of the kidney on the left and right is taken as 5 cm from the vertical midline and is on the transpyloric plane.[6]

Vasculature

The superior mesenteric artery arises from the aorta at the level of the transpyloric plane and emerges between the head and neck of the pancreas.[8]

The superior mesenteric vein is joined by the splenic vein to form the portal vein at the level of the transpyloric plane.[2][8]

Spleen

The lower border of the spleen lies near the transpyloric plane.[8]

Other structures

- the left and right colic flexure[2]

- the root of the transverse mesocolon.[2]

- cisterna chyli (which drains into the thoracic duct).[8]

History

The transpyloric plane relates to the three-dimensional mapping of the abdomen founded on more than 10,000 measurements completed on 40 bodies, that surgeon Viscount Addison took at the turn of the 20th century.[9]

Addison reported his findings in a paper titled, "On the anatomical topography of the abdominal viscera in man, especially the gastro-intestinal canal" in which he established a baseline for the anatomy of the abdomen based on the arrangement of the map of the Earth. Using the suprasternal notch as the North Pole of the trunk, and the upper border of the pubic symphysis as the South Pole, he drew a vertical line joining these two points as his meridian. At the meridian's midpoint, he then drew a perpendicular line corresponding to the Equator. As this transverse plane crossed the pylorus, he called it the transpyloric plane.[10]

Images

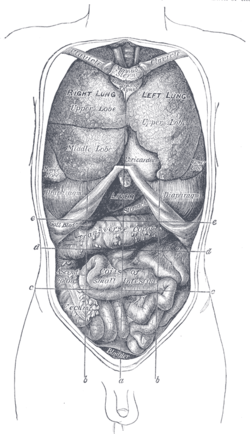

Front view of the thoracic and abdominal viscera.

Front view of the thoracic and abdominal viscera.

a. Median plane.

b. Lateral planes.

c. Trans tubercular plane.

d. Subcostal plane.

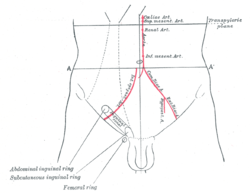

e. Transpyloric plane. Front of abdomen, showing surface markings for arteries and inguinal canal.

Front of abdomen, showing surface markings for arteries and inguinal canal.

See also

References

- Singh, Vishram. (2014). Textbook of Anatomy Abdomen and Lower Limb Volume 2 (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 26. ISBN 978-81-312-3626-0.

- Sinnatamby, Chummy S. (2011). "5". Last's Anatomy e-Book: Regional and Applied (12th ed.). Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-4839-5. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Snell, Richard S. (2012). Clinical Anatomy by Regions (9th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-60913-446-4.

- Elliott L. Mancall; David G. Brock (2011). Gray's Clinical Neuroanatomy E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4377-3580-2.

- Drake, Richard L.; Wayne, Vogl A.; Mitchell, Adam W.M. (2015). Gray's Anatomy for Students (3rd ed.) Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. p. 311.

- Gray, Henry; Lewis, Warren Harmon (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body (20th ed.). Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. pp. 1320–1321.

- Constantine C. Karaliotas; Christoph E. Broelsch; Nagy A. Habib (Eds.) (2008). Liver and Biliary Tract Surgery: Embryological Anatomy to 3D-Imaging and Transplant Innovations. Springer Wien New York. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-3-211-49277-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Herbert H, Srebnik (2002). Concepts in Anatomy. USA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-0-7923-7539-5. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Addison, Sir Christopher, Viscount Addison of Stallingborough (1869 - 1951). Royal College of Surgeons: Plarr's Lives of the Fellows Online. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Keith, Arthur (1 March 1952). "Lord Addison as Anatomist". British Journal of Surgery. 39 (157): 385–387. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003915702. ISSN 1365-2168.(subscription required)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1315 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)