Tourette syndrome

Tourette syndrome (TS or simply Tourette's) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder with onset in childhood,[4] characterized by multiple motor tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic. These tics characteristically wax and wane, can be suppressed temporarily, and are typically preceded by an unwanted urge or sensation in the affected muscles. Some common tics are eye blinking, coughing, throat clearing, sniffing, and facial movements. Tourette's does not adversely affect intelligence or life expectancy.

| Tourette syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tourette's syndrome, Tourette's disorder, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) |

| |

| Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1857–1904), namesake of Tourette syndrome | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, neurology |

| Symptoms | Tics[1] |

| Usual onset | Typically in childhood[1] |

| Duration | Long term[2] |

| Causes | Genetic with environmental influence[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on history and symptoms[1] |

| Treatment | Education, behavioral therapy[1][3] |

| Medication | Usually none, occasionally antipsychotics and noradrenergics[1] |

| Prognosis | Improvement to disappearance of tics beginning in late teens[2] |

| Frequency | About 1%[1] |

Tourette's is defined as part of a spectrum of tic disorders, which includes provisional, transient and persistent (chronic) tics. Tics are often unnoticed by casual observers. While the exact cause is unknown, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There are no specific tests for diagnosing Tourette's; it is not always correctly identified because most cases are mild and the severity of tics decreases for most children as they pass through adolescence. Extreme Tourette's in adulthood, though sensationalized in the media, is a rarity.

In most cases, medication for tics is not necessary. Education is an important part of any treatment plan, and explanation and reassurance alone are often sufficient treatment.[1][5] Many individuals with Tourette's go undiagnosed or never seek medical care. Among those who are seen in specialty clinics, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) are present at higher rates. These co-occurring diagnoses often cause more impairment to the individual than the tics; hence, it is important to correctly identify associated conditions and treat them.[6]

About 1% of school-age children and adolescents have Tourette's.[1] It was once considered a rare and bizarre syndrome, most often associated with coprolalia (the utterance of obscene words or socially inappropriate and derogatory remarks), but this symptom is present in only a small minority of people with Tourette's.[3] The condition was named by Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) on behalf of his resident, Georges Albert Édouard Brutus Gilles de la Tourette (1857–1904), a French physician and neurologist, who published an account of nine patients with Tourette's in 1885.

Classification

Tics are sudden, repetitive, nonrhythmic movements (motor tics) and utterances (phonic tics) that involve discrete muscle groups.[7] Joseph Jankovic describes vocal or phonic tics as "motor tics that involve respiratory, laryngeal, pharyngeal, oral, and nasal musculature".[8]

Tourette's was classified by the fourth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) as one of several tic disorders "usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence" according to type (motor or phonic tics) and duration (transient or chronic). Transient tic disorders consisted of multiple motor tics, phonic tics or both, with a duration between four weeks and twelve months. Chronic tic disorder was either single or multiple, motor or phonic tics (but not both), which were present for more than a year.[7] Tourette's was diagnosed when multiple motor tics, and at least one phonic tic, are present for more than a year.[9] The fifth version of the DSM (DSM-5), published in May 2013, reclassified Tourette's and tic disorders as motor disorders listed in the neurodevelopmental disorder category, and replaced transient tic disorder with provisional tic disorder, but made few other significant changes.[10][11][12] Tic disorders are defined only slightly differently by the World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-10; code F95.2 is for combined vocal and multiple motor tic disorder [de la Tourette].[13]

Although Tourette's is the more severe expression of the spectrum of tic disorders,[14] most cases are mild[15] and many individuals with TS do not come to clinical attention.[1] The severity of symptoms varies widely among people with Tourette's, and mild cases may be undetected.[7]

Characteristics

Tics are movements or sounds "that occur intermittently and unpredictably out of a background of normal motor activity",[16] having the appearance of "normal behaviors gone wrong".[17] The tics associated with Tourette's change in number, frequency, severity and anatomical location. Waxing and waning—the ongoing increase and decrease in severity and frequency of tics—occurs differently in each individual. Tics may also occur in "bouts of bouts", which vary for each person.[7]

Coprolalia (the spontaneous utterance of socially objectionable or taboo words or phrases) is the most publicized symptom of Tourette's, but it is not required for a diagnosis of Tourette's and only about 10% of Tourette's patients exhibit it.[1][3] Echolalia (repeating the words of others) and palilalia (repeating one's own words) occur in a minority of cases,[7] while the most common initial motor and vocal tics are, respectively, eye blinking and throat clearing.[18]

In contrast to the abnormal movements of other movement disorders such as choreas, dystonias, myoclonus, and dyskinesias, the tics of Tourette's are temporarily suppressible, nonrhythmic, and often preceded by an unwanted premonitory urge.[19] Immediately preceding tic onset, most individuals with Tourette's are aware of an urge,[20][21] similar to the need to sneeze or scratch an itch. Individuals describe the need to tic as a buildup of tension, pressure, or energy[21][22] which they consciously choose to release, as if they "had to do it"[23] to relieve the sensation[21] or until it feels "just right".[23][24] Examples of the premonitory urge are the feeling of having something in one's throat, or a localized discomfort in the shoulders, leading to the need to clear one's throat or shrug the shoulders. The actual tic may be felt as relieving this tension or sensation, similar to scratching an itch. Another example is blinking to relieve an uncomfortable sensation in the eye. These urges and sensations, preceding the expression of the movement or vocalization as a tic, are referred to as "premonitory sensory phenomena" or premonitory urges. Because of the urges that precede them, tics are described as semi-voluntary or "unvoluntary",[1][16] rather than specifically involuntary; they may be experienced as a voluntary, suppressible response to the unwanted premonitory urge.[3] Published descriptions of the tics of Tourette's identify sensory phenomena as the core symptom of the syndrome, even though they are not included in the diagnostic criteria.[22][25][26]

| Video clips of tics |

|---|

While individuals with tics are sometimes able to suppress their tics for limited periods of time, doing so often results in tension or mental exhaustion.[1][3] People with Tourette's may seek a secluded spot to release their symptoms, or there may be a marked increase in tics after a period of suppression at school or at work.[17] Some people with Tourette's may not be aware of the premonitory urge. Children may be less aware of the premonitory urge associated with tics than are adults, but their awareness tends to increase with maturity.[16] They may have tics for several years before becoming aware of premonitory urges. Children may suppress tics while in the doctor's office, so they may need to be observed while they are not aware they are being watched.[27] The ability to suppress tics varies among individuals, and may be more developed in adults than children.

Although there is no such thing as a typical case of Tourette syndrome,[28] the condition follows a fairly reliable course in terms of the age of onset and the history of the severity of symptoms. Tics may appear up to the age of eighteen, but the most typical age of onset is from five to seven.[1] A 1998 study published by Leckman and colleagues from the Yale Child Study Center[29] showed that the ages of highest tic severity are eight to twelve (with an average of age ten), with tics steadily declining for most patients as they pass through adolescence.[24][30] The most common, first-presenting tics are eye blinking, facial movements, sniffing and throat clearing. Initial tics present most frequently in midline body regions where there are many muscles, usually the head, neck and facial region.[28] This can be contrasted with the stereotyped movements of other disorders (such as stims and stereotypies of the autism spectrum disorders), which typically have an earlier age of onset; are more symmetrical; rhythmical and bilateral; and involve the extremities, e.g., flapping the hands.[31] Tics that appear early in the course of the condition are frequently confused with other conditions, such as allergies, asthma, and vision problems: pediatricians, allergists and ophthalmologists are typically the first to identify a child as having tics.[7]

Most cases of Tourette's in older individuals are mild and almost unnoticeable.[32] Adults with TS presenting in clinics are atypical.[1] When symptoms are severe enough to warrant referral to clinics, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are often associated with Tourette's.[1] In children with tics, the additional presence of ADHD is associated with functional impairment, disruptive behavior, and tic severity.[33] Compulsions resembling tics are present in some individuals with OCD; "tic-related OCD" is hypothesized to be a subgroup of OCD, distinguished from non-tic related OCD by the type and nature of obsessions and compulsions.[34] Not all persons with Tourette's have ADHD or OCD or other comorbid conditions, although in clinical populations, a high percentage of patients presenting for care do have ADHD.[24][35] One author reports that a ten-year overview of patient records revealed about 40% of people with Tourette's have "TS-only" or "pure TS", referring to Tourette syndrome in the absence of ADHD, OCD and other disorders.[36][37] Another author reports that 57% of 656 patients presenting with tic disorders had uncomplicated tics, while 43% had tics plus comorbid conditions.[17] People with "full-blown Tourette's" have significant comorbid conditions in addition to tics.[17] Several reports have documented a comorbidity between Tourette syndrome and Asperger syndrome, or high-functioning autism.[38][39][40][41] One study found that 8% of young people with autism had comorbid Tourette syndrome, while a second found that 20% of Swedish school-age children with Asperger syndrome also met full criteria for Tourette syndrome, with 80% having tics of some kind or another. In another study, 10% of children with Tourette syndrome also met full criteria for Asperger syndrome.[41] A 2017 study elucidated that, despite a consistent finding of higher comorbidity between autism and Tourette syndrome, some of it may be in part down to difficulty in discriminating between tics and tic-like behaviours in autism as well as OCD symptoms.[42]

Causes

The exact cause of Tourette's is unknown, but it is well established that both genetic and environmental factors are involved.[43] Genetic epidemiology studies have shown that the overwhelming majority of cases of Tourette's are inherited, although the exact mode of inheritance is not yet known and no gene has been identified.[6][44][45] In other cases, tics are associated with disorders other than Tourette's, a phenomenon known as tourettism.[46]

A person with Tourette's has about a 50% chance of passing the gene(s) to one of his or her children, but Tourette's is a condition of variable expression and incomplete penetrance.[47] Thus, not everyone who inherits the genetic vulnerability will show symptoms; even close family members may show different severities of symptoms, or no symptoms at all. The gene(s) may express as Tourette's, as a milder tic disorder (provisional or chronic tics), or as obsessive–compulsive symptoms without tics. Only a minority of the children who inherit the gene(s) have symptoms severe enough to require medical attention.[48] Gender appears to have a role in the expression of the genetic vulnerability: males are more likely than females to express tics.[27]

Non-genetic, environmental, post-infectious, or psychosocial factors—while not causing Tourette's—can influence its severity.[28] Autoimmune processes may affect tic onset and exacerbation in some cases. In 1998, a team at the US National Institute of Mental Health proposed a hypothesis based on observation of 50 children that both obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and tic disorders may arise in a subset of children as a result of a poststreptococcal autoimmune process.[15] Children who meet five diagnostic criteria are classified, according to the hypothesis, as having Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections (PANDAS).[49] This contentious hypothesis is the focus of clinical and laboratory research, but remains unproven.[3][15][50]

Some forms of OCD may be genetically linked to Tourette's.[24][51] A subset of OCD is thought to be causally related to Tourette's and may be a different expression of the same factors that are important for the expression of tics.[52] The genetic relationship of ADHD to Tourette syndrome, however, has not been fully established.[37]

Pathophysiology

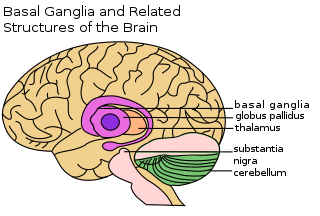

The exact mechanism affecting the inherited vulnerability to Tourette's has not been established, and the precise cause is unknown. Tics are believed to result from dysfunction in cortical and subcortical regions, the thalamus, basal ganglia and frontal cortex.[43] Neuroanatomic models implicate failures in circuits connecting the brain's cortex and subcortex:[28] imaging techniques implicate the basal ganglia and frontal cortex.[44] After 2010, the role of histamine and the H3-receptor came into focus in the pathophysiology of TS,[53] as "key modulators of striatal circuitry".[54][55] A reduced level of histamine in the H3-receptor may disrupt other neurotransmitters, causing tics.[56]

Diagnosis

According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), Tourette's may be diagnosed when a person exhibits both multiple motor and one or more vocal tics over the period of a year; the motor and vocal tics need not be concurrent. The onset must have occurred before the age of 18, and cannot be attributed to the effects of another condition or substance (such as cocaine).[9] Hence, other medical conditions that include tics or tic-like movements—such as autism or other causes of tourettism—must be ruled out before conferring a Tourette's diagnosis. Since 2000, the DSM has recognized that clinicians see patients who meet all the other criteria for Tourette's, but do not have distress or impairment.[57][58][59]

There are no specific medical or screening tests that can be used in diagnosing Tourette's;[24] it is frequently misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed, partly because of the wide expression of severity, ranging from mild (the majority of cases) or moderate, to severe (the rare, but more widely recognized and publicized cases).[29] Coughing, eye blinking, and tics that mimic unrelated conditions such as asthma are commonly misdiagnosed.[3] The diagnosis is made based on observation of the individual's symptoms and family history,[3] and after ruling out secondary causes of tic disorders.[48] In patients with a typical onset and a family history of tics or obsessive–compulsive disorder, a basic physical and neurological examination may be sufficient.[14]

There is no requirement that other comorbid conditions, such as ADHD or OCD, be present,[3] but if a physician believes that there may be another condition present that could explain tics, tests may be carried out to rule out that condition. An example of this is when diagnostic confusion between tics and seizure activity exists, which would call for an EEG, or if there are symptoms that indicate an MRI to rule out brain abnormalities.[60] TSH levels can be measured to rule out hypothyroidism, which can be a cause of tics. Brain imaging studies are not usually warranted.[60] In teenagers and adults presenting with a sudden onset of tics and other behavioral symptoms, a urine drug screen for cocaine and stimulants might be necessary. If a family history of liver disease is present, serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels can rule out Wilson's disease.[14] Most cases are diagnosed by merely observing a history of tics.[28]

Secondary causes of tics (not related to inherited Tourette syndrome) are commonly referred to as tourettism.[46] Dystonias, choreas, other genetic conditions, and secondary causes of tics should be ruled out in the differential diagnosis for Tourette syndrome.[14] Other conditions that may manifest tics or stereotyped movements include developmental disorders; autism spectrum disorders[61] and stereotypic movement disorder;[62][63] Sydenham's chorea; idiopathic dystonia; and genetic conditions such as Huntington's disease, neuroacanthocytosis, pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Wilson's disease, and tuberous sclerosis. Other possibilities include chromosomal disorders such as Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, XYY syndrome and fragile X syndrome. Acquired causes of tics include drug-induced tics, head trauma, encephalitis, stroke, and carbon monoxide poisoning.[14][46] The symptoms of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome may also be confused with Tourette syndrome.[31] Most of these conditions are rarer than tic disorders, and a thorough history and examination may be enough to rule them out, without medical or screening tests.[28]

Screening

Although not all people with Tourette's have comorbid conditions, most Tourette's patients presenting for clinical care at specialty referral centers may exhibit symptoms of other conditions along with their motor and phonic tics.[37] Associated conditions include attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD or ADHD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), learning disabilities, Asperger syndrome[41] and sleep disorders.[3] Disruptive behaviors, impaired functioning, or cognitive impairment in patients with comorbid Tourette's and ADHD may be accounted for by the comorbid ADHD, highlighting the importance of identifying and treating comorbid conditions.[3][6][24][35] Disruption from tics is commonly overshadowed by comorbid conditions that present greater interference to the child.[28] Tic disorders in the absence of ADHD do not appear to be associated with disruptive behavior or functional impairment,[64] while impairment in school, family, or peer relations is greater in patients who have more comorbid conditions and often determines whether therapy is needed.[17]

Because comorbid conditions such as OCD and ADHD can be more impairing than tics, these conditions are included in an evaluation of patients presenting with tics. "It is critical to note that the comorbid conditions may determine functional status more strongly than the tic disorder", according to Samuel Zinner, MD.[28] The initial assessment of a patient referred for a tic disorder should include a thorough evaluation, including a family history of tics, ADHD, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, and other chronic medical, psychiatric and neurological conditions. Children and adolescents with TS who have learning difficulties are candidates for psychoeducational testing, particularly if the child also has ADHD.[60] Undiagnosed comorbid conditions may result in functional impairment, and it is necessary to identify and treat these conditions to improve functioning. Complications may include depression, sleep problems, social discomfort, self-injury,[14] anxiety, personality disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorders.[33]

Management

Treatment of Tourette's is individualized and involves a collaboration between the clinician, individual with TS, and caregivers where applicable.[30] It is focused on identifying and helping the individual manage the most troubling or impairing symptoms.[3] Most cases of Tourette's are mild, and do not require pharmacological treatment;[48] instead, psychobehavioral therapy, education, and reassurance may be sufficient,[65] and "watchful waiting is an acceptable approach" for those without "functional impairment from their tics".[30] Treatments, where warranted, can be divided into those that target tics and comorbid conditions, which, when present, are often a larger source of impairment than the tics themselves.[60] Not all people with tics have comorbid conditions,[37] but when those conditions are present, they often take treatment priority.[30]

There is no cure for Tourette's and no medication that works universally for all individuals without significant adverse effects. Knowledge, education and understanding are uppermost in management plans for tic disorders.[3] The management of the symptoms of Tourette's may include pharmacological, behavioral and psychological therapies. While pharmacological intervention is reserved for more severe symptoms, other treatments, such as supportive psychotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, may help to avoid or ameliorate depression and social isolation, and to improve family support. Educating a patient, family, and surrounding community (such as friends, school, and church) is a key treatment strategy, and may be all that is required in mild cases.[3][66] Practice guidelines for the treatment of tics were published by the American Academy of Neurology in 2019.[30]

Medication is available to help when symptoms interfere with functioning.[48] The classes of medication with the most proven efficacy in treating tics—typical and atypical neuroleptics including risperidone (trade name[67] Risperdal), ziprasidone (Geodon), haloperidol (Haldol), pimozide (Orap) and fluphenazine (Prolixin)—can have long-term and short-term adverse effects.[60] The antihypertensive agents clonidine (trade name Catapres) and guanfacine (Tenex) are also used to treat tics; studies show variable efficacy, but a lower side effect profile than the neuroleptics.[68] Stimulants and other medications may be useful in treating ADHD when it co-occurs with tic disorders. Drugs from several other classes of medications can be used when stimulants fail, including guanfacine (trade name Tenex), atomoxetine (Strattera) and tricyclic antidepressants. Clomipramine (Anafranil), a tricyclic, and SSRIs—a class of antidepressants including fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), and fluvoxamine (Luvox)—may be prescribed when a Tourette's patient also has symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Several other medications have been tried, but evidence to support their use is unconvincing.[60]

Because children with tics often present to physicians when their tics are most severe, and because of the waxing and waning nature of tics, it is recommended that medication not be started immediately or changed often.[28] Frequently, the tics subside with explanation, reassurance, understanding of the condition and a supportive environment.[28] When medication is used, the goal is not to eliminate symptoms: it is used at the lowest dose that manages symptoms without adverse effects, given that these may be more disturbing than the symptoms for which the medication was prescribed.[28]

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a useful treatment when OCD is present.[69] Other behavioral therapies including habit reversal training (HRT)/comprehensive behavioral intervention (CBIT) and exposure and response prevention (ERP) are first-line interventions,[70] subject to some limitations: children younger than ten may not understand the treatment, people with severe tics or ADHD may not be able to suppress their tics or sustain the required focus to benefit from behavioral treatments, and there is a lack of therapists trained in behavioral interventions.[71]

Relaxation techniques, such as exercise, yoga or meditation, may be useful in relieving the stress that may aggravate tics, but the majority of behavioral interventions (such as relaxation training and biofeedback, with the exception of habit reversal) have not been systematically evaluated and are not empirically supported therapies for Tourette's.[72] Complementary and alternative medicine approaches, such as dietary modification, allergy testing and allergen control, and neurofeedback, have popular appeal, but no role has been proven for any of these in the treatment of Tourette syndrome.[73] As of 2018, in spite of no evidence base supporting dietary approaches to management of TS symptoms, anecdotal reports indicate that parents, caregivers, and individuals with TS are using dietary approaches and nutritional supplements nonetheless.[74] Deep brain stimulation has been used to treat adults with severe Tourette's that does not respond to conventional treatment, but it is regarded as an invasive, experimental procedure that is unlikely to become widespread.[3][15][6][75][76]

Prognosis

Tourette syndrome is a spectrum disorder—its severity ranges over a spectrum from mild to severe. The majority of cases are mild and require no treatment.[48] In these cases, the impact of symptoms on the individual may be mild, to the extent that casual observers might not know of their condition. The overall prognosis is positive, but a minority of children with Tourette syndrome have severe symptoms that persist into adulthood.[43] A study of 46 subjects at 19 years of age found that the symptoms of 80% had minimum to mild impact on their overall functioning, and that the other 20% experienced at least a moderate impact on their overall functioning.[7] The rare minority of severe cases can inhibit or prevent individuals from holding a job or having a fulfilling social life. In a follow-up study of thirty-one adults with Tourette's, all patients completed high school, 52% finished at least two years of college, and 71% were full-time employed or were pursuing higher education.[82]

Regardless of symptom severity, individuals with Tourette's have a normal life span. Although the symptoms may be lifelong and chronic for some, the condition is not degenerative or life-threatening. Intelligence is normal in those with Tourette's, although there may be learning disabilities.[3] Severity of tics early in life does not predict tic severity in later life,[3] and prognosis is generally favorable,[83] although there is no reliable means of predicting the outcome for a particular individual. The gene or genes associated with Tourette's have not been identified, and there is no potential cure.[83] A higher rate of migraines than the general population and sleep disturbances are reported.[83]

Several studies have demonstrated that the condition in most children improves with maturity. Tics may be at their highest severity at the time that they are diagnosed, and often improve with understanding of the condition by individuals and their families and friends. The statistical age of highest tic severity is typically between eight and twelve, with most individuals experiencing steadily declining tic severity as they pass through adolescence. One study showed no correlation between tic severity and the onset of puberty, in contrast with the popular belief that tics increase at puberty. In many cases, a complete remission of tic symptoms occurs after adolescence.[29][84] However, a study using videotape to record tics in adults found that, although tics diminished in comparison with childhood, and all measures of tic severity improved by adulthood, 90% of adults still had tics. Half of the adults who considered themselves tic-free still displayed evidence of tics.[82]

Many people with TS may not realize they have tics; because tics are more commonly expressed in private, TS may go unrecognized or undetected.[86] It is not uncommon for the parents of affected children to be unaware that they, too, may have had tics as children. Because Tourette's tends to subside with maturity, and because milder cases of Tourette's are now more likely to be recognized, the first realization that a parent had tics as a child may not come until their offspring is diagnosed. It is not uncommon for several members of a family to be diagnosed together, as parents bringing children to a physician for an evaluation of tics become aware that they, too, had tics as a child.

Children with Tourette's may suffer socially if their tics are viewed as "bizarre". If a child has disabling tics, or tics that interfere with social or academic functioning, supportive psychotherapy or school accommodations can be helpful.[48] Because comorbid conditions such as ADHD or OCD can cause greater impact on overall functioning than tics, a thorough evaluation for comorbidity is called for when symptoms and impairment warrant.[14]

A supportive environment and family generally gives those with Tourette's the skills to manage the disorder.[87][88] People with Tourette's may learn to camouflage socially inappropriate tics or to channel the energy of their tics into a functional endeavor. Accomplished musicians, athletes, public speakers, and professionals from all walks of life are found among people with Tourette's. Outcomes in adulthood are associated more with the perceived significance of having severe tics as a child than with the actual severity of the tics. A person who was misunderstood, punished, or teased at home or at school is likely to fare worse than a child who enjoyed an understanding and supportive environment.[7]

Epidemiology

Tourette syndrome is found among all social, racial and ethnic groups and has been reported in all parts of the world;[3][24] it is three to four times more frequent among males than among females.[15] The tics of Tourette syndrome begin in childhood and tend to remit or subside with maturity; thus, a diagnosis may no longer be warranted for many adults, and observed prevalence rates are higher among children than adults.[29] As children pass through adolescence, about one-quarter become tic-free, almost one-half see their tics diminish to a minimal or mild level, and less than one-quarter have persistent tics. Only 5 to 14% of adults experience worse tics in adulthood than in childhood.[3][6]

Up to 1% of the overall population experiences tic disorders, including chronic tics and transient tics of childhood.[64] Chronic tics affect 5% of children, and transient tics affect up to 20%.[89] Prevalence rates in special education populations are higher.[15] The reported prevalence of TS varies "according to the source, age, and sex of the sample; the ascertainment procedures; and diagnostic system",[24] with a range reported between 0.4% and 3.8% for children ages 5 to 18.[32] Robertson (2011) says that 1% of school-age children have Tourette's.[15] According to Lombroso and Scahill (2008), the emerging consensus is that 0.1 to 1% of children have Tourette's,[90] with several studies supporting a tighter range of 0.6 to 0.8%.[64] Bloch and Leckman (2009) and Swain (2007) report a range of prevalence in children of 0.4 to 0.6%,[24][89] Knight et al. (2012) estimate 0.77% in children,[86] and Du et al. (2010) report that 1 to 3% of Western school-age children have Tourette's.[6]

Singer (2011) states the prevalence of TS in the overall population at any time is 0.1% for impairing cases and 0.6% for all cases,[3] while Bloch and colleagues (2011) state the overall prevalence as between 0.3 and 1%.[44] Robertson (2011) also suggests that the rate of Tourette's in the general population is 1%.[15] Using year 2000 census data, a prevalence range of 0.1 to 1% yields an estimate of 53,000–530,000 school-age children with Tourette's in the US,[64] and a prevalence estimate of .1% means that in 2001 about 553,000 people in the UK age 5 or older would have Tourette's.[32]

Tourette syndrome was once thought to be rare: in 1972, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) believed there were fewer than 100 cases in the United States,[91] and a 1973 registry reported only 485 cases worldwide.[92] However, multiple studies published since 2000 have consistently demonstrated that the prevalence is much higher than previously thought.[93] Discrepancies between current and prior prevalence estimates come from several factors: ascertainment bias in earlier samples drawn from clinically referred cases; assessment methods that may fail to detect milder cases; and differences in diagnostic criteria and thresholds.[93] There were few broad-based community studies published before 2000 and until the 1980s, most epidemiological studies of Tourette syndrome were based on individuals referred to tertiary care or specialty clinics.[94] Individuals with mild symptoms may not seek treatment and physicians may not confer an official diagnosis of TS on children out of concern for stigmatization;[86] children with milder symptoms are unlikely to be referred to specialty clinics, so prevalence studies have an inherent bias towards more severe cases.[95] Studies of Tourette syndrome are vulnerable to error because tics vary in intensity and expression, are often intermittent, and are not always recognized by clinicians, patients, family members, friends or teachers.[28][96] Approximately 20% of persons with Tourette syndrome do not recognize that they have tics.[28] Newer studies—recognizing that tics may often be undiagnosed and hard to detect—use direct classroom observation and multiple informants (parents, teachers, and trained observers), and therefore record more cases than older studies relying on referrals.[66][97] As the diagnostic threshold and assessment methodology have moved towards recognition of milder cases, there has been an increase in estimated prevalence.[93]

Tourette's is associated with several comorbid conditions, or co-occurring diagnoses, which are often the major source of impairment for an affected child.[24][44] Most individuals with tics do not seek medical attention, so epidemiological studies of TS "reflect a strong ascertainment bias",[44] but among those who do warrant medical attention, the majority have other conditions, and up to 50% have ADHD or OCD.[44]

History

The first presentation of Tourette syndrome is thought to be in the book, Malleus Maleficarum (Witch's Hammer) by Jakob Sprenger and Heinrich Kraemer, published in the late 15th century and describing a priest whose tics were "believed to be related to possession by the devil".[98][99] A French doctor, Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, reported the first case of Tourette syndrome in 1825,[100] describing the Marquise de Dampierre, an important woman of nobility in her time.[101] Jean-Martin Charcot, an influential French physician, assigned his resident Georges Albert Édouard Brutus Gilles de la Tourette, a French physician and neurologist, to study patients at the Salpêtrière Hospital, with the goal of defining an illness distinct from hysteria and chorea.[27]

In 1885, Gilles de la Tourette published an account in Study of a Nervous Affliction describing nine persons with "convulsive tic disorder", concluding that a new clinical category should be defined.[102][103] The eponym was later bestowed by Charcot after and on behalf of Gilles de la Tourette.[27][104]

Little progress was made over the next century in explaining or treating tics, and a psychogenic view prevailed well into the 20th century.[27] The possibility that movement disorders, including Tourette syndrome, might have an organic origin was raised when an encephalitis epidemic from 1918–1926 led to a subsequent epidemic of tic disorders.[105]

During the 1960s and 1970s, as the beneficial effects of haloperidol (Haldol) on tics became known, the psychoanalytic approach to Tourette syndrome was questioned.[106] The turning point came in 1965, when Arthur K. Shapiro—described as "the father of modern tic disorder research"[107]—treated a Tourette's patient with haloperidol, and published a paper criticizing the psychoanalytic approach.[105]

Since the 1990s, a more neutral view of Tourette's has emerged, in which biological vulnerability and adverse environmental events are seen to interact.[27][28] In 2000, the American Psychiatric Association published the DSM-IV-TR, revising the text of DSM-IV to no longer require that symptoms of tic disorders cause distress or impair functioning,[57] recognizing that clinicians often see patients who meet all the other criteria for Tourette's, but do not have distress or impairment.[58][59]

Findings since 1999 have advanced TS science in the areas of genetics, neuroimaging, neurophysiology, and neuropathology. Questions remain regarding how best to classify Tourette syndrome, and how closely Tourette's is related to other movement or psychiatric disorders. Good epidemiologic data is still lacking, and available treatments are not risk free and not always well tolerated.[108] High-profile media coverage focuses on treatments that do not have established safety or efficacy, such as deep brain stimulation, and alternative therapies involving unstudied efficacy and side effects are pursued by many parents.[50]

Society and culture

Not everyone with Tourette's wants treatment or a "cure", especially if that means they may "lose" something else in the process.[109][110] Researchers Leckman and Cohen, and former US Tourette Syndrome Association (TSA) national board member Kathryn Taubert, believe that there may be latent advantages associated with an individual's genetic vulnerability to developing Tourette syndrome, such as a heightened awareness and increased attention to detail and surroundings that may have adaptive value.[111] There is evidence to support the clinical lore that children with "TS-only" (Tourette's in the absence of comorbid conditions) are unusually gifted: neuropsychological studies have identified advantages in children with TS-only.[37][112] Children with TS-only are faster than the average for their age group on timed tests of motor coordination.[37][113]

Notable individuals with Tourette syndrome are found in all walks of life, including musicians, athletes, media figures, teachers, physicians, and authors.[114] A well-known example of a person who may have used obsessive–compulsive traits to advantage is Samuel Johnson, the 18th-century English man of letters, who likely had Tourette syndrome as evidenced by the writings of James Boswell.[115][116] Johnson wrote A Dictionary of the English Language in 1747, and was a prolific writer, poet, and critic. Tim Howard, described by the Chicago Tribune as the "rarest of creatures—an American soccer hero"[117] and by the TSA as the "most notable individual with Tourette Syndrome around the world"[118] says that his neurological makeup gave him an enhanced perception and an ability to hyper-focus that contributed to his success on the field.[85]

Although it has been speculated that Mozart had Tourette's,[119][120] no Tourette's expert or organization has presented credible evidence to support such a conclusion,[120] and there are problems with the arguments supporting the diagnosis: tics are not transferred to the written form, as is supposed with Mozart's scatological writings; the medical history in retrospect is not thorough; side effects due to other conditions may be misinterpreted; "it is not proven whether written documents can account for the existence of a vocal tic" and "the evidence of motor tics in Mozart's life is doubtful".[121]

Pre-dating Gilles de la Tourette's 1885 publication, likely portrayals of TS or tic disorders in fictional literature are Mr. Pancks in Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens and Nikolai Levin in Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy.[122] The entertainment industry has been criticized for depicting those with Tourette syndrome as social misfits whose only tic is coprolalia, which has furthered stigmatization and the public's misunderstanding of those with Tourette's.[123] The coprolalic symptoms of Tourette's are also fodder for radio and television talk shows in the US[124] and for the British media.[125]

References

- Stern JS. "Tourette's syndrome and its borderland" (PDF). Archived December 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Pract Neurol. 2018 Aug;18(4):262–70. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2017-001755 PMID 29636375.

- Tourette syndrome fact sheet. Archived December 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. July 6, 2018. Retrieved on November 30, 2018.

- Singer HS. "Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders". Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;100:641–57. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00046-X PMID 21496613. Also see Singer HS. "Tourette's syndrome: from behaviour to biology". Lancet Neurol. 2005 Mar;4(3):149–59. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01012-4 PMID 15721825.

- Jankovic J. Movement Disorders, An Issue of Neurologic Clinics. The Clinics: Radiology: Elsevier, 2014, p. viii

- Peterson BS, Cohen DJ. "The treatment of Tourette's Syndrome: multimodal, developmental intervention". J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 1:62–72; discussion 73–74. PMID 9448671. Quote: "Because of the understanding and hope that it provides, education is also the single most important treatment modality that we have in TS." Also see Zinner 2000.

- Du JC, Chiu TF, Lee KM, et al. "Tourette syndrome in children: an updated review". Pediatr Neonatol. 2010 Oct;51(5):255–64. doi:10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60050-2 PMID 20951354

- Leckman JF, Bloch MH, King RA, Scahill L. "Phenomenology of tics and natural history of tic disorders". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:1–16. PMID 16536348

- Jankovic, J. "Tics and Tourette Syndrome". Practical Neurology September 2017:22–24.

- "Tourette's Disorder, 307.23 (F95.2)". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 2013, Fifth edition. American Psychiatric Association, p. 81.

- Neurodevelopmental disorders. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved on December 29, 2011.

- Moran, M. "DSM-5 provides new take on neurodevelopment disorders". Psychiatric News. 18 January 2013;48(2):6–23. doi:10.1176/appi.pn.2013.1b11

- "Highlights of changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Retrieved on June 5, 2013.

- Du, Chiu, Lee, et al. 2010. See also ICD version 2007. Archived March 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine World Health Organization. Retrieved on December 29, 2011.

- Bagheri MM, Kerbeshian J, Burd L. "Recognition and management of Tourette's syndrome and tic disorders". Archived March 31, 2005, at the Wayback Machine American Family Physician. 1999; 59:2263–74. PMID 10221310 Retrieved on October 28, 2006.

- Robertson MM. "Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the complexities of phenotype and treatment". Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2011 Feb;72(2):100–07. PMID 21378617

- The Tourette Syndrome Classification Study Group. "Definitions and classification of tic disorders". Arch Neurol. 1993 Oct;50(10):1013–16. PMID 8215958 Archived April 26, 2006.

- Dure LS 4th, DeWolfe J. "Treatment of tics". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:191–96. PMID 16536366

- Malone DA Jr, Pandya MM. "Behavioral neurosurgery". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:241–47. PMID 16536372

- Jankovic J. "Differential diagnosis and etiology of tics". Adv Neurol. 2001;85:15–29. PMID 11530424

- Cohen AJ, Leckman JF. "Sensory phenomena associated with Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome". J Clin Psychiatry. 1992 Sep;53(9):319–23. PMID 1517194

- Prado HS, Rosário MC, Lee J, Hounie AG, Shavitt RG, Miguel EC. "Sensory phenomena in obsessive–compulsive disorder and tic disorders: a review of the literature". Archived February 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine CNS Spectr. 2008;13(5):425–32. PMID 18496480.

- Bliss J. "Sensory experiences of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980 Dec;37(12):1343–47. PMID 6934713

- Kwak C, Dat Vuong K, Jankovic J. "Premonitory sensory phenomenon in Tourette's syndrome". Mov Disord. 2003 Dec;18(12):1530–33. doi:10.1002/mds.10618 PMID 14673893

- Swain JE, Scahill L, Lombroso PJ, King RA, Leckman JF. "Tourette syndrome and tic disorders: a decade of progress". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Aug;46(8):947–68 doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e318068fbcc PMID 17667475

- Scahill LD, Leckman JF, Marek KL. "Sensory phenomena in Tourette's syndrome". Adv Neurol. 1995;65:273–80. PMID 7872145

- Miguel EC, do Rosario-Campos MC, Prado HS, et al. "Sensory phenomena in obsessive–compulsive disorder and Tourette's disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 2000 Feb;61(2):150–56. PMID 10732667

- Black, KJ. Tourette Syndrome and Other Tic Disorders. Archived August 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine eMedicine (March 30, 2007). Retrieved on August 10, 2009.

- Zinner SH. "Tourette disorder". Pediatr Rev. 2000;21(11):372–83. PMID 11077021

- Leckman JF, Zhang H, Vitale A, et al. "Course of tic severity in Tourette syndrome: the first two decades. (PDF). Pediatrics. 1998;102 (1 Pt 1):14–19. PMID 9651407.

- Pringsheim T, Okun MS, Müller-Vahl K, et al. "Practice guideline recommendations summary: Treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders". Neurology. May 6, 2019;92(19):896–906. PMID 31061208 doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007466

- Rapin I. "Autism spectrum disorders: relevance to Tourette syndrome". Adv Neurol. 2001;85:89–101. PMID 11530449

- Robertson MM. "The prevalence and epidemiology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Part 1: the epidemiological and prevalence studies". J Psychosom Res. 2008 Nov;65(5):461–72. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.006 PMID 18940377

- Robertson MM. "The prevalence and epidemiology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Part 2: tentative explanations for differing prevalence figures in GTS, including the possible effects of psychopathology, aetiology, cultural differences, and differing phenotypes". J Psychosom Res. 2008 Nov;65(5):473–86. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.007 PMID 18940378

- Hounie AG, do Rosario-Campos MC, Diniz JB, et al. "Obsessive-compulsive disorder in Tourette syndrome". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:22–38. PMID 16536350

- Spencer T, Biederman J, Harding M, et al. "Disentangling the overlap between Tourette's disorder and ADHD". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998 Oct;39(7):1037–44. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00406 PMID 9804036

- Denckla MB. "Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) comorbidity: a case for "pure" Tourette syndrome?" J Child Neurol. 2006 Aug;21(8):701–03. PMID 16970871

- Denckla MB. "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the childhood co-morbidity that most influences the disability burden in Tourette syndrome". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:17–21. PMID 16536349

- Rapin I (2001). "Autism spectrum disorders: relevance to Tourette syndrome". Advances in Neurology. 85: 89–101. PMID 11530449.

- Steyaert JG, De la Marche W (2008). "What's new in autism?". Eur J Pediatr. 167 (10): 1091–101. doi:10.1007/s00431-008-0764-4. PMID 18597114.

- Mazzone, Luigi; Ruta, Liliana; Reale, Laura (2012). "Psychiatric comorbidities in asperger syndrome and high functioning autism: Diagnostic challenges". Annals of General Psychiatry. 11 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-11-16. PMC 3416662. PMID 22731684.

- Gillberg C, Billstedt E (November 2000). "Autism and Asperger syndrome: coexistence with other clinical disorders". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 102 (5): 321–30. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102005321.x. PMID 11098802.

- Sabrina M. Darrow; et al. (2017). "Autism Spectrum Symptoms in a Tourette Syndrome Sample". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 56 (7): 610–17. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.002. PMC 5648014. PMID 28647013.

- Walkup, JT, Mink, JW, Hollenback, PJ, (eds). Advances in Neurology, Tourette syndrome. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. 2006;99:xv. ISBN 0-7817-9970-8 Google books. Archived May 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Bloch M, State M, Pittenger C. "Recent advances in Tourette syndrome". Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011 Apr;24(2):119–25. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328344648c PMID 21386676

- O'Rourke JA, Scharf JM, Yu D, et al. "The genetics of Tourette syndrome: A review". J Psychosom Res. 2009 Dec;67(6):533–45. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.06.006 PMID 19913658

- Mejia NI, Jankovic J. "Secondary tics and tourettism" Archived June 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27(1):11–17. PMID 15867978

- van de Wetering BJ, Heutink P. "The genetics of the Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a review". J Lab Clin Med. 1993 May;121(5):638–45. PMID 8478592

- Tourette Syndrome: Frequently Asked Questions. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved on May 8, 2013.

- PANDAS. Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine NIH. Retrieved on November 25, 2006.

- Swerdlow, NR. "Tourette Syndrome: Current Controversies and the Battlefield Landscape". Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005, 5:329–31. doi:10.1007/s11910-005-0054-8 PMID 16131414

- Pauls DL, Towbin KE, Leckman JF, et al. "Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Evidence supporting a genetic relationship". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986 Dec;43(12):1180–82. PMID 3465280

- Miguel EC, do Rosario-Campos MC, Shavitt RG, et al. "The tic-related obsessive–compulsive disorder phenotype and treatment implications". Adv Neurol. 2001;85:43–55. PMID 11530446

- Rapanelli M, Pittenger C. "Histamine and Histamine Receptors in Tourette Syndrome and Other Neuropsychiatric Conditions". Neuropharmacology, 2016 Jul;106:85–90. PMID 26282120 doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.019

- Rapanelli, Maximiliano. "The Magnificent Two: Histamine and the H3 Receptor as Key Modulators of Striatal Circuitry". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 2017 Feb 6;73:36–40. PMID 27773554 doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.10.002

- Bolam, J. Paul, and Tommas J. Ellender. "Histamine and the Striatum". Neuropharmacology, 2016 Jul;106:74–84. PMID 26275849 doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.013

- Sadek B, Saad A, Sadeq A, Jalal F, Stark H. "Histamine H3 Receptor as a Potential Target for Cognitive Symptoms in Neuropsychiatric Diseases". Behavioural Brain Research 2016 Oct 1;312:415–30. PMID 27363923 doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.051

- Walkup JT, Ferrão Y, Leckman JF, Stein DJ, Singer H. "Tic disorders: some key issues for DSM-V". Archived January 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Depress Anxiety. 2010 Jun;27(6):600–10. doi:10.1002/da.20711 PMID 20533370

- Summary of Practice: Relevant changes to DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved from May 11, 2008 archive.org version on December 29, 2011.

- What is DSM-IV-TR? Retrieved on October 28, 2006.

- Scahill L, Erenberg G, Berlin CM Jr, Budman C, Coffey BJ, Jankovic J, Kiessling L, King RA, Kurlan R, Lang A, Mink J, Murphy T, Zinner S, Walkup J; Tourette Syndrome Association Medical Advisory Board: Practice Committee. "Contemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndrome" (PDF). NeuroRx. 2006 Apr;3(2):192–206. doi:10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.009 PMID 16554257

- Ringman JM, Jankovic J. "Occurrence of tics in Asperger's syndrome and autistic disorder". J Child Neurol. 2000 Jun;15(6):394–400. PMID 10868783

- Jankovic J, Mejia NI. "Tics associated with other disorders". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:61–68. PMID 16536352

- Freeman, RD. Tourette's Syndrome: minimizing confusion Archived April 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Roger Freeman, MD, blog. Retrieved on February 8, 2006.

- Scahill L, Williams S, Schwab-Stone M, Applegate J, Leckman JF. "Disruptive behavior problems in a community sample of children with tic disorders". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:184–90. PMID 16536365

- Robertson MM. "Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment". Archived June 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Brain. 2000;123 Pt 3:425–62. doi:10.1093/brain/123.3.425 PMID 10686169

- Stern JS, Burza S, Robertson MM. "Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and its impact in the UK". Postgraduate Medicine Journal. 2005 Jan;81(951):12–19. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.023614 PMID 15640424

- Medication trade names may differ between countries. In general, this article uses North American trade names.

- Bloch, State, Pittenger 2011. See also Schapiro NA. "Dude, you don't have Tourette's:" Tourette's syndrome, beyond the tics. Pediatr Nurs. 2002 May–Jun;28(3):243–46, 249–53. PMID 12087644 Full text (free registration required). Archived December 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Coffey BJ, Shechter RL. "Treatment of co-morbid obsessive compulsive disorder, mood, and anxiety disorders". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:208–21. PMID 16536368

- Fründt O, Woods D, Ganos C. "Behavioral therapy for Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders". Neurol Clin Pract. 2017 Apr;7(2):148–56. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000348 PMID 29185535

- Ganos C, Martino D, Pringsheim T. "Tics in the pediatric population: Pragmatic management". Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2017 Mar–Apr;4(2):160–72. doi:10.1002/mdc3.12428 PMID 28451624

- Woods DW, Himle MB, Conelea CA. "Behavior therapy: other interventions for tic disorders". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:234–40. PMID 16536371

- Zinner SH. "Tourette syndrome—much more than tics". Contemporary Pediatrics. Aug 2004;21(8):22–49. Part 1 PDF Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Part 2 PDF Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Ludlow AK, Rogers SL. "Understanding the impact of diet and nutrition on symptoms of Tourette syndrome: A scoping review". J Child Health Care. 2018 Mar;22(1):68–83. doi:10.1177/1367493517748373 PMID 29268618

- Statement: Deep Brain Stimulation and Tourette Syndrome. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved on February 26, 2005.

- Viswanathan A, Jimenez-Shahed J, Baizabal Carvallo JF, Jankovic J. Deep brain stimulation for Tourette syndrome: target selection. Archived October 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2012;90(4):213–24. PMID 22699684 doi:10.1159/000337776

- Kammer T. "Mozart in the neurological department—who has the tic?" (PDF). Front Neurol Neurosci. 2007;22:184–92. doi:10.1159/0000102880 PMID 17495512

- What is Tourette Syndrome? Tourette Syndrome Foundation of Canada. Retrieved on July 2, 2013.

- Todd, Olivier. Malraux: A Life. Knopf, 2005.

- Guidotti TL. André Malraux: a medical interpretation (PDF). J R Soc Med. 1985 May;78(5):401–06. PMID 3886907

- Liebmann, Lisa. Lisa Liebmann on the Mona Lisa. TATEetc. Issue 6 / Spring 2006. Retrieved on March 1, 2008.

- Pappert EJ, Goetz CG, Louis ED, et al. "Objective assessments of longitudinal outcome in Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome". Neurology. 2003 Oct 14;61(7):936–40. PMID 14557563

- Singer HS. "Tourette's syndrome: from behaviour to biology". Lancet Neurol. 2005 Mar;4(3):149–59. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)01012-4 PMID 15721825

- Burd L, Kerbeshian PJ, Barth A, et al. "Long-term follow-up of an epidemiologically defined cohort of patients with Tourette syndrome". J Child Neurol. 2001;16(6):431–37. PMID 11417610

- Howard, Tim. Tim Howard: Growing up with Tourette syndrome and my love of football. Archived November 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The Guardian. December 6, 2014. Retrieved on March 21, 2015.

- Knight T, Steeves T, Day L, Lowerison M, Jette N, Pringsheim T. Prevalence of tic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Neurol. 2012 Aug;47(2):77–90. PMID 22759682 doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.05.002

- Leckman JF, Cohen DJ. Tourette's Syndrome—Tics, Obsessions, Compulsions: Developmental Psychopathology and Clinical Care. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. 1999:37. ISBN 0-471-16037-7 Google books. Archived May 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine "For example, individuals who were misunderstood and punished at home and at school for their tics or who were teased mercilessly by peers and stigmatized by their communities will fare worse than a child whose interpersonal environment was more understanding and supportive."

- Cohen DJ, Leckman JF, Pauls D. "Neuropsychiatric disorders of childhood: Tourette’s syndrome as a model". Acta Paediatr Suppl 422; 106–11, Scandinavian University Press, 1997. "The individuals with TS who do the best, we believe, are: those who have been able to feel relatively good about themselves and remain close to their families; those who have the capacity for humor and for friendship; those who are less burdened by troubles with attention and behavior, particularly aggression; and those who have not had development derailed by medication."

- Bloch MH, Leckman JF. "Clinical course of Tourette syndrome". J Psychosom Res. 2009 Dec;67(6):497–501. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.002 PMID 19913654

- Lombroso PJ, Scahill L. "Tourette syndrome and obsessive–compulsive disorder". Brain Dev. 2008 Apr;30(4):231–37. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2007.09.001 PMID 17937978

- Cohen DJ, Jankovic J, Goetz CG, (eds). Advances in Neurology, Tourette syndrome. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. 2001;85:xviii. ISBN 0-7817-2405-8

- Abuzzahab FE, Anderson FO. "Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome; international registry". Minnesota Medicine. 1973 Jun;56(6):492–96. PMID 4514275

- Scahill, L. "Epidemiology of Tic Disorders". Medical Letter: 2004 Retrospective Summary of TS Literature. Tourette Syndrome Association. The first page (PDF), is available at archive.org without subscription. Retrieved on June 11, 2007.

- Bloch, State, Pittenger 2011. See also Zohar AH, Apter A, King RA, et al. "Epidemiological studies". In Leckman JF, Cohen DJ. Tourette's Syndrome—Tics, Obsessions, Compulsions: Developmental Psychopathology and Clinical Care. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. 1999:177–92. ISBN 0-471-16037-7

- Bloch, State, Pittenger 2011. See also Schapiro 2002 and Coffey BJ, Park KS. "Behavioral and emotional aspects of Tourette syndrome". Neurol Clin. 1997 May;15(2):277–89. PMID 9115461

- Hawley, JS. Tourette Syndrome. Archived August 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine eMedicine (June 23, 2008). Retrieved on August 10, 2009.

- Leckman JF. "Tourette's syndrome". Lancet. 2002 Nov 16;360(9345):1577–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11526-1 PMID 12443611

- Teive HA, Chien HF, Munhoz RP, Barbosa ER. "Charcot's contribution to the study of Tourette's syndrome". Archived January 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008 Dec;66(4):918–21. PMID 19099145 as reported in Finger S. "Some movement disorders." In Finger S (ed). Origins of neuroscience: the history of explorations into brain function. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994:220–39.

- Germiniani FM, Miranda AP, Ferenczy P, Munhoz RP, Teive HA. Tourette's syndrome: from demonic possession and psychoanalysis to the discovery of gene. Archived October 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2012 Jul;70(7):547–49. PMID 22836463

- Itard JMG. "Mémoire sur quelques functions involontaires des appareils de la locomotion, de la préhension et de la voix". Arch Gen Med. 1825;8:385–407. From Newman, Sara. "Study of several involuntary functions of the apparatus of movement, gripping, and voice" by Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard (1825) History of Psychiatry. 2006;17:333–39. doi:10.1177/0957154X06067668

- What is Tourette syndrome? Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved on January 14, 2012.

- Gilles de la Tourette G, Goetz CG, Llawans HL, trans. "Étude sur une affection nerveuse caractérisée par de l'incoordination motrice accompagnée d'echolalie et de coprolalie". In: Friedhoff AJ, Chase TN, eds. Advances in Neurology: Volume 35. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. New York: Raven Press; 1982;1–16. Discussed at Black, KJ. Tourette Syndrome and Other Tic Disorders. Archived August 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine eMedicine (March 30, 2007). Retrieved on August 10, 2009. Original text (in French). Archived January 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on August 10, 2009.

- Robertson MM, Reinstein DZ. "Convulsive tic disorder: Georges Gilles de la Tourette, Guinon and Grasset on the phenomenology and psychopathology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome". Behavioural Neurology, 1991;4(1), 29–56.

- Enersen, Ole Daniel. Georges Albert Édouard Brutus Gilles de la Tourette. Archived March 9, 2005, at the Wayback Machine WhoNamedIt.com Retrieved on May 14, 2007.

- Blue, Tina. Tourette syndrome. Essortment 2002. Pagewise Inc. Retrieved on August 10, 2009.

- Rickards H, Hartley N, Robertson MM. "Seignot's paper on the treatment of Tourette's syndrome with haloperidol. Classic Text No. 31". Hist Psychiatry. 1997 Sep;8 (31 Pt 3):433–36. PMID 11619589

- Gadow KD, Sverd J. "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, chronic tic disorder, and methylphenidate". Adv Neurol. 2006;99:197–207. PMID 16536367

- Walkup, JT, Mink, JW, Hollenback, PJ, (eds). Advances in Neurology, Tourette syndrome. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. 2006;99:xvi–xviii. ISBN 0-7817-9970-8 Google books. Archived May 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Sacks, O. The man who mistook his wife for a hat: and other clinical tales. Harper and Row, New York. 1985:92–100. ISBN 0-684-85394-9

- Leckman JF, Cohen DJ. Tourette's Syndrome—Tics, Obsessions, Compulsions: Developmental Psychopathology and Clinical Care. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. 1999:408. ISBN 0-471-16037-7

- Leckman JF, Cohen DJ. Tourette's Syndrome—Tics, Obsessions, Compulsions: Developmental Psychopathology and Clinical Care. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. 1999:18–19, 148–51; 408. ISBN 0-471-16037-7

- Schuerholz LJ, Baumgardner TL, Singer HS, et al. "Neuropsychological status of children with Tourette's syndrome with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Neurology. 1996 Apr;46(4):958–65. PMID 8780072

- Schuerholz LJ, Cutting L, Mazzocco MM, et al. "Neuromotor functioning in children with Tourette syndrome with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". J Child Neurol. 1997 Oct;12(7):438–42. PMID 9373800

- Portraits of adults with TS. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved from July 16, 2011 archive.org version on December 21, 2011.

- Samuel Johnson. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved from April 7, 2005 archive.org version on December 30, 2011.

- Pearce JM. "Doctor Samuel Johnson: 'the great convulsionary' a victim of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1994 Jul;87(7):396–99. PMID 8046726

- Keilman, John. Reviews: The Game of Our Lives by David Goldblatt, The Keeper by Tim Howard. Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune. January 22, 2015. Retrieved on March 21, 2015.

- Tim Howard receives first-ever Champion of Hope Award from the National Tourette Syndrome Association. Archived March 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Tourette Syndrome Association. October 14, 2014. Retrieved on March 21, 2015.

- Simkin B. "Mozart's scatological disorder". BMJ. 1992 Dec 19–26;305(6868):1563–67. PMID 1286388 Also see: Simkin, Benjamin. Medical and Musical Byways of Mozartiana. Fithian Press. 2001. ISBN 1-56474-349-7 Review Archived December 7, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on May 14, 2007.

- Did Mozart really have TS? Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved from April 7, 2005 archive.org version on December 30, 2011.

- Mozart:

- Kammer T. "Mozart in the neurological department—who has the tic?" (PDF). Front Neurol Neurosci. 2007;22:184–92. PMID 17495512 doi:10.1159/0000102880 Retrieved on February 7, 2012.

- Ashoori A, Jankovic J. "Mozart's movements and behaviour: a case of Tourette's syndrome?" J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007 Nov;78(11):1171–75 doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.114520 PMID 17940168.

- Sacks O. "Tourette's syndrome and creativity". BMJ. 1992 Dec 19–26;305(6868):1515–16. doi:10.1136/bmj.305.6868.1515 PMID 1286364

- Voss H. "The representation of movement disorders in fictional literature". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012 Oct;83(10):994–99. PMID 22752692 doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-302716

- Holtgren, Bruce. "Truth about Tourette's not what you think". Cincinnati Enquirer. January 11, 2006. "As medical problems go, Tourette's is, except in the most severe cases, about the most minor imaginable thing to have. ... the freak-show image, unfortunately, still prevails overwhelmingly. The blame for the warped perceptions lies overwhelmingly with the video media—the Internet, movies and TV. If you search for 'Tourette' on Google or YouTube, you'll get a gazillion hits that almost invariably show the most outrageously extreme examples of motor and vocal tics. Television, with notable exceptions such as Oprah, has sensationalized Tourette's so badly, for so long, that it seems beyond hope that most people will ever know the more prosaic truth."

- US media:

- Oprah and Dr. Laura – Conflicting Messages on Tourette Syndrome. Oprah Educates; Dr. Laura Fosters Myth of TS as "Cursing Disorder". Tourette Syndrome Association. May 31, 2001. Retrieved from October 6, 2001 archive.org version on December 21, 2011.

- Letter of response to Dr. Phil. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved from August 31, 2008 archive.org version on December 21, 2011.

- Letter of response to Garrison Keillor radio show. Tourette Syndrome Association. Retrieved from February 7, 2009 archive.org version on December 21, 2011.

-

UK media:

- Guldberg, Helene. Stop celebrating Tourette's. Archived March 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Spiked. May 26, 2006. Retrieved on December 26, 2006.

Further reading

- Kushner, HI. A Cursing Brain?: The Histories of Tourette Syndrome. Harvard University Press. 2000. ISBN 0-674-00386-1.

- Olson, S. "Making Sense of Tourette's" (PDF). Science. 2004 Sep 3;305(5689):1390–92. doi:10.1126/science.305.5689.1390 PMID 15353772

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tourette syndrome. |

- Tourette syndrome at Curlie

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|