Tooth eruption

Tooth eruption is a process in tooth development in which the teeth enter the mouth and become visible. It is currently believed that the periodontal ligament plays an important role in tooth eruption. The first human teeth to appear, the deciduous (primary) teeth (also known as baby or milk teeth), erupt into the mouth from around 6 months until 2 years of age, in a process known as "teething". These teeth are the only ones in the mouth until a person is about 6 years old creating the primary dentition stage. At that time, the first permanent tooth erupts and begins a time in which there is a combination of primary and permanent teeth, known as the mixed dentition stage, which lasts until the last primary tooth is lost. Then, the remaining permanent teeth erupt into the mouth during the permanent dentition stage.

Theories

Although researchers agree that tooth eruption is a complex process, there is little agreement on the identity of the mechanism that controls eruption.[1] There have been many theories over time that have been eventually disproven.[2] According to Growth Displacement Theory, tooth is pushed upward into the mouth by the growth of the tooth's root in opposite direction. Continued Bone Formation Theory advocated that a tooth is pushed upward by the growth of the bone around the tooth. In addition, some believed teeth were pushed upward by vascular pressure or by an anatomic feature called the cushioned hammock. The cushioned hammock theory, first proposed by Harry Sicher, was taught widely from the 1930s to the 1950s. This theory postulated that a ligament below a tooth, which Sicher observed under a microscope on a histologic slide, was responsible for eruption. Later, the "ligament" Sicher observed was determined to be merely an artifact created in the process of preparing the slide.[3]

The most widely held current theory is that while several forces might be involved in eruption, the periodontal ligament provides the main impetus for the process. Theorists hypothesize that the periodontal ligament promotes eruption through the shrinking and cross-linking of their collagen fibers and the contraction of their fibroblasts.[4]

There is good evidence from experimental animals that a traction force is unlikely to be involved in tooth eruption: Animals treated with lathyrogens that interfere with collagen cross-link formation showed similar eruption rates to control animals, provided occlusal forces were removed.

Inherent in most of the theories outlined above, is the idea that a force is generated in the periodontal ligament beneath unerupted teeth, and that this force physically drives teeth out through the bone. This idea may have been superseded by a further recent theory. This new theory proposes firstly that areas of tension and compression are generated in the soft tissues surrounding unerupted teeth by the distribution of bite forces through the jaws. These patterns of tension and compression, are further proposed to result in patterns of bone resorption and deposition that lift the tooth into the mouth.[5] This theory is based on Wolff's Law, which is the long established idea that bone changes shape in accordance with the forces applied.[6] Significantly, a recent finite element analysis study, analysing the distribution of force through the jaw of an 8-year-old child, observed overall compression in the soft tissues above, and tension in the soft tissues below, unerupted teeth.[5] Because bone resorbs when compressed, and forms under tension, this finite element analysis strongly supports the new theory.[5] Further work is required, however, to confirm this new theory experimentally.

Timeline

Although tooth eruption occurs at different times for different people, a general eruption timeline exists. Typically, humans have 20 primary teeth and 32 permanent teeth.[7] The dentition goes through three stages.[8] The first, known as primary dentition stage, occurs when only primary teeth are visible. Once the first permanent tooth erupts into the mouth, the teeth that are visible are in the mixed (or transitional) dentition stage. After the last primary tooth is shed or exfoliates out of the mouth, the teeth are in the permanent dentition stage. Each patient should be assigned a dentition period to allow for effective dental treatment.[8]

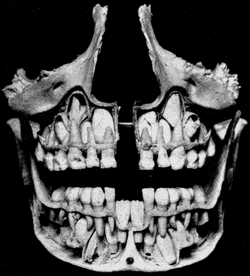

Primary dentition stage

Primary dentition stage starts on the arrival of the mandibular central incisors, typically from around six months, and lasts until the first permanent molars appear in the mouth, usually at six years.[9] There are 20 primary teeth and they typically erupt in the following order: (1) central incisor, (2) lateral incisor, (3) first molar, (4) canine, and (5) second molar.[10] As a general rule, four teeth erupt for every six months of life, mandibular teeth erupt before maxillary teeth, and teeth erupt sooner in females than males.[11] During primary dentition, the tooth buds of permanent teeth develop inferior to the primary teeth, close to the palate or tongue.

Mixed dentition stage

Mixed dentition stage starts when the first permanent tooth appears in the mouth, usually at five or six years with the first permanent molar, and lasts until the last primary tooth is lost, usually at ten, eleven, or twelve years.[12] There are 32 permanent teeth and those of the maxillae erupt in a different order from permanent mandibular teeth. Maxillary teeth typically erupt in the following order: (1) first molar (2) central incisor, (3) lateral incisor, (4) first premolar, (5) second premolar, (6) canine, (7) second molar, and (8) third molar. Mandibular teeth typically erupt in the following order: (1) first molar (2) central incisor, (3) lateral incisor, (4) canine, (5) first premolar, (6) second premolar, (7) second molar, and (8) third molar.[13] While this is the most common eruption order, variation is common.

Since there are no premolars in the primary dentition, the primary molars are replaced by permanent premolars.[14][15] If any primary teeth are shed or lost before permanent teeth are ready to replace them, some posterior teeth may drift forward and cause space to be lost in the mouth.[16][17] This may cause crowding and/or misplacement once the permanent teeth erupt, which is usually referred to as malocclusion. Orthodontics may be required in such circumstances for an individual to achieve a functioning and aesthetic dentition.

Permanent dentition stage

The permanent dentition begins when the last primary tooth is lost, usually at 11 to 12 years, and lasts for the rest of a person's life or until all of the teeth are lost (edentulism). During this stage, permanent third molars (also called "wisdom teeth") are frequently extracted because of decay, pain or impactions. The main reasons for tooth loss are decay or periodontal disease.[18]

Active vs. Passive Eruption

Active Eruption

Active eruption is known as eruption of teeth into the mouth towards the occlusal plane. This is a natural path of eruption of all the teeth as they emerge from gingiva and continue erupting until they make contact with the opposing tooth.

Passive Eruption

Passive eruption is known as movement of the gingiva apically or away from the crown of the tooth to the level of Cementoenamel junction (CEJ) after the tooth has erupted completely. Problems in gingival tissue migrating apically can give rise to what is known as Altered or Delayed passive eruption.[19] In this phenomenon, the gingival tissues fail to move apically and thus lead to shorter clinical crowns with more square-shaped teeth and appearance of what is known as Gummy smile.

Coslet Classification

Coslet et al.[20] classified delayed passive eruption into two types which related the bone crest of a tooth to the Mucogingival junction (MGJ) of that tooth. These two groups were further divided based on the position of the alveolar bone crest to the cementoenamel junction.

| Type | Osseous crest level | Attached gingival level | Gingival margin level | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1a | Apical to CEJ | Adequate | Incisal to CEJ | Gingivectomy |

| Type 1b | At CEJ | Adequate | Incisal to CEJ | Gingivectomy and osseous surgery |

| Type 2a | Apical to CEJ | Inadequate | Incisal to CEJ | Apically positioned flap |

| Type 2b | At CEJ | Inadequate | Incisal to CEJ | Apically positioned flap and osseous surgery |

Abnormalities

Abnormalities in tooth eruption (timing and sequence) is often caused by genetics and may result in malocclusion. In severe cases, such as in Down syndrome, the eruption may be delayed by several years and some teeth may never erupt.[21][22][23][24]

See also

References

- Riolo, Michael L. and James K. Avery. Essentials for Orthodontic Practice. 1st edition. 2003. p. 142. ISBN 0-9720546-0-X.

- Harris, Edward F. Craniofacial Growth and Development. In the section titled "Tooth Eruption." 2002. pp. 1–3.

- Harris, Edward F. Craniofacial Growth and Development. In the section titled "Tooth Eruption." 2002. p. 3.

- Harris, Edward F. Craniofacial Growth and Development. In the section titled "Tooth Eruption." 2002. p. 5.

- Sarrafpour, Babak; Swain, Michael; Li, Qing; Zoellner, Hans (2013-03-15). "Tooth Eruption Results from Bone Remodelling Driven by Bite Forces Sensed by Soft Tissue Dental Follicles: A Finite Element Analysis". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58803. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058803. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3598949. PMID 23554928.

- Frost, H.M. (Feb 2004). "A 2003 update of bone physiology and Wolff's Law for clinicians". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. Angle Orthodontist. 66 (4): 1349–56. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(75)90508-2. PMID 5.

- The American Dental Association, Tooth Eruption Charts at http://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/e/eruption-charts.aspx

- Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 191-192

- Ash, Major M. and Stanley J. Nelson. Wheeler’s Dental Anatomy, Physiology, and Occlusion. 8th edition. 2003. P. 38, 41. ISBN 0-7216-9382-2.

- Ash, Major M. and Stanley J. Nelson. Wheeler’s Dental Anatomy, Physiology, and Occlusion. 8th edition. 2003. P. 38. ISBN 0-7216-9382-2.

- WebMd. "Dental Health: Your Child's Teeth". Retrieved December 12, 2005.

- Ash, Major M.; Nelson, Stanley J. (2003). Wheeler's Dental Anatomy, Physiology, and Occlusion (8th ed.). p. 41. ISBN 0-7216-9382-2.

- "Permanent teeth". American Dental Association.

- "Monthly Microscopy Explorations". Archived from the original on 1 December 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2005.

- "Exploration of the Month". January 1998. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2005.

- "Health Hawaii".

- "Primary Teeth: Importance and Care". Health Hawaii. Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2005.

- The American Academy of Periodontology Archived 2005-12-14 at the Wayback Machine. "Oral Health Information for the Public" Archived 2006-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 12, 2005.

- Alpiste-Illueca, Francisco (2011-01-01). "Altered passive eruption (APE): a little-known clinical situation". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 16 (1): e100–104. doi:10.4317/medoral.16.e100. ISSN 1698-6946. PMID 20711147.

- Coslet, J. G.; Vanarsdall, R.; Weisgold, A. (1977-12-01). "Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult". The Alpha Omegan. 70 (3): 24–28. ISSN 0002-6417. PMID 276255.

- Wysocki, J. Philip Sapp; Lewis R. Eversole; George P. (2002). Contemporary oral and maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. pp. 39–40. ISBN 0-323-01723-1.

- Cawson, R.A.; Odell, E.W. (2012). Cawson's essentials of oral pathology and oral medicine (8th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 419–421. ISBN 978-0443-10125-0.

- Dean, Ralph E. McDonald; David R. Avery; Jeffrey A. (2004). Dentistry for the child and adolescent (8. ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Mosby. pp. 164–168, 190–194, 474. ISBN 0-323-02450-5.

- Regezi, Joseph A; Sciubba, James J; Jordan, Richard C K (2008). Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations (5th ed.). St Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier. pp. 353–354.