Thyroid cancer

Thyroid cancer is cancer that develops from the tissues of the thyroid gland.[1] It is a disease in which cells grow abnormally and have the potential to spread to other parts of the body.[7][8] Symptoms can include swelling or a lump in the neck.[1] Cancer can also occur in the thyroid after spread from other locations, in which case it is not classified as thyroid cancer.[3]

| Thyroid cancer | |

|---|---|

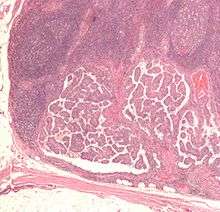

.jpg) | |

| Micrograph of a papillary thyroid carcinoma demonstrating diagnostic features (nuclear clearing and overlapping nuclei). | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Swelling or lump in the neck[1] |

| Risk factors | Radiation exposure, enlarged thyroid, family history[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Ultrasound, fine needle aspiration[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Thyroid nodule, metastatic disease[1][3] |

| Treatment | Surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, thyroid hormone, targeted therapy, watchful waiting[1] |

| Prognosis | Five year survival rates 98% (US)[4] |

| Frequency | 3.2 million (2015)[5] |

| Deaths | 31,900 (2015)[6] |

Risk factors include radiation exposure at a young age, having an enlarged thyroid, and family history.[1][2] The four main types are papillary thyroid cancer, follicular thyroid cancer, medullary thyroid cancer, and anaplastic thyroid cancer.[3] Diagnosis is often based on ultrasound and fine needle aspiration.[1] Screening people without symptoms and at normal risk for the disease is not recommended as of 2017.[9]

Treatment options may include surgery, radiation therapy including radioactive iodine, chemotherapy, thyroid hormone, targeted therapy, and watchful waiting.[1] Surgery may involve removing part or all of the thyroid.[3] Five-year survival rates are 98% in the United States.[4]

Globally as of 2015, 3.2 million people have thyroid cancer.[5] In 2012, 298,000 new cases occurred.[10] It most commonly occurs between the ages of 35 and 65.[4] Women are affected more often than men.[4] Those of Asian descent are more commonly affected.[3] Rates have increased in the last few decades, which is believed to be due to better detection.[10] In 2015, it resulted in 31,900 deaths.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Most often, the first symptom of thyroid cancer is a nodule in the thyroid region of the neck.[11] However, up to 65% of adults have small nodules in their thyroids, but typically under 10% of these nodules are found to be cancerous.[12] Sometimes, the first sign is an enlarged lymph node. Later symptoms that can be present are pain in the anterior region of the neck and changes in voice due to an involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Thyroid cancer is usually found in a euthyroid patient, but symptoms of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism may be associated with a large or metastatic, well-differentiated tumor.

Thyroid nodules are of particular concern when they are found in those under the age of 20. The presentation of benign nodules at this age is less likely, thus the potential for malignancy is far greater.

Causes

Thyroid cancers are thought to be related to a number of environmental and genetic predisposing factors, but significant uncertainty remains regarding their causes.

Environmental exposure to ionizing radiation from both natural background sources and artificial sources is suspected to play a significant role, and significantly increased rates of thyroid cancer occur in those exposed to mantlefield radiation for lymphoma, and those exposed to iodine-131 following the Chernobyl,[13] Fukushima, Kyshtym, and Windscale[14] nuclear disasters.[15] Thyroiditis and other thyroid diseases also predispose to thyroid cancer.[14][16]

Genetic causes include multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, which markedly increases rates, particularly of the rarer medullary form of the disease.[17]

Diagnosis

After a thyroid nodule is found during a physical examination, a referral to an endocrinologist or a thyroidologist may occur. Most commonly, an ultrasound is performed to confirm the presence of a nodule and assess the status of the whole gland. Measurement of thyroid stimulating hormone and antithyroid antibodies will help decide if a functional thyroid disease such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis is present, a known cause of a benign nodular goiter.[18] Measurement of calcitonin is necessary to exclude the presence of medullary thyroid cancer. Finally, to achieve a definitive diagnosis before deciding on treatment, a fine needle aspiration cytology test is usually performed and reported according to the Bethesda system.

In adults without symptoms, screening for thyroid cancer is not recommended.[19]

Classification

Thyroid cancers can be classified according to their histopathological characteristics.[20][21] These variants can be distinguished (distribution over various subtypes may show regional variation):

- Papillary thyroid cancer (75 to 85% of cases[22]) – often in young females – excellent prognosis. May occur in women with familial adenomatous polyposis and in patients with Cowden syndrome.

- Newly reclassified variant: noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features is considered an indolent tumor of limited biologic potential.

- Follicular thyroid cancer (10 to 20% of cases[22]) – occasionally seen in people with Cowden syndrome. Some include Hürthle cell carcinoma as a variant and others list it as a separate type.[3][23]

- Medullary thyroid cancer (5[22] to 8% of cases) – cancer of the parafollicular cells, often part of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2.[24]

- Poorly differentiated thyroid cancer

- Anaplastic thyroid cancer (less than 5% of cases[22]) is not responsive to treatment and can cause pressure symptoms.

- Others

The follicular and papillary types together can be classified as "differentiated thyroid cancer".[25] These types have a more favorable prognosis than the medullary and undifferentiated types.[26]

- Papillary microcarcinoma is a subset of papillary thyroid cancer defined as measuring less than or equal to 1 cm. [27] 43% of all thyroid cancers and 50% of new cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma are papillary microcarcinoma.[28][29] Management strategies for incidental papillary microcarcinoma on ultrasound (and confirmed on FNAB) range from total thyroidectomy with radioactive iodine ablation to observation alone. Harach et al. suggest using the term "occult papillary tumor" to avoid giving patients distress over having cancer. Woolner et al. first arbitrarily coined the term "occult papillary carcinoma", in 1960, to describe papillary carcinomas ≤ 1.5 cm in diameter.[30]

Staging

Cancer staging is the process of determining the extent of the development of a cancer. The TNM staging system is usually used to classify stages of cancers, but not of the brain.

Stage M1 thyroid cancer

Stage M1 thyroid cancer Stage N1a thyroid cancer

Stage N1a thyroid cancer Stage N1b thyroid cancer

Stage N1b thyroid cancer Stage T1a thyroid cancer

Stage T1a thyroid cancer Stage T1b thyroid cancer

Stage T1b thyroid cancer Stage T2 thyroid cancer

Stage T2 thyroid cancer Stage T3 thyroid cancer

Stage T3 thyroid cancer Stage T4a thyroid cancer

Stage T4a thyroid cancer Stage T4b thyroid cancer

Stage T4b thyroid cancer

Metastases

Detection of any metastases of thyroid cancer can be performed with a full-body scintigraphy using iodine-131.[31][32]

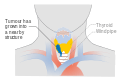

Spread

Thyroid cancer can spread directly, via lymphatics or blood. Direct spread occurs through infiltration of the surrounding tissues. The tumor infiltrates into infrahyoid muscles, trachea, oesophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve, carotid sheath, etc. The tumor then becomes fixed. Anaplastic carcinoma spreads mostly by direct spread, while papillary carcinoma spreads so the least. Lymphatic spread is most common in papillary carcinoma. Cervical lymph nodes become palpable in papillary carcinoma even when the primary tumor is unpalpable. Deep cervical nodes, pretracheal, prelaryngeal, and paratracheal groups of lymph nodes are often affected. The lymph node affected is usually the same side as that of the location of the tumor. Blood spread is also possible in thyroid cancers, especially in follicular and anaplastic carcinoma. The tumor emboli do angioinvasion of lungs; end of long bones, skull, and vertebrae are affected. Pulsating metastases occur because of their increased vascularity.[33]

Treatment

Thyroidectomy and dissection of central neck compartment is initial step in treatment of thyroid cancer in the majority of cases.[11] Thyroid-preserving operations may be applied in cases, when thyroid cancer exhibits low biological aggressiveness (e.g. well-differentiated cancer, no evidence of lymph-node metastases, low MIB-1 index, no major genetic alterations like BRAF mutations, RET/PTC rearrangements, p53 mutations etc.) in patients younger than 45 years.[34] If the diagnosis of well-differentiated thyroid cancer (e.g. papillary thyroid cancer) is established or suspected by FNA, then surgery is indicated, whereas watchful waiting strategy is not recommended in any evidence-based guidelines.[34][35] Watchful waiting reduces overdiagnosis and overtreatment of thyroid cancer among old patients.[36]

Radioactive iodine-131 is used in people with papillary or follicular thyroid cancer for ablation of residual thyroid tissue after surgery and for the treatment of thyroid cancer.[37] Patients with medullary, anaplastic, and most Hurthle-cell cancers do not benefit from this therapy.[11]

External irradiation may be used when the cancer is unresectable, when it recurs after resection, or to relieve pain from bone metastasis.[11]

Sorafenib and lenvatinib are approved for advanced metastatic thyroid cancer.[38] Numerous agents are in phase II and III clinical trials.[38]

Prognosis

The prognosis of thyroid cancer is related to the type of cancer and the stage at the time of diagnosis. For the most common form of thyroid cancer, papillary, the overall prognosis is excellent. Indeed, the increased incidence of papillary thyroid carcinoma in recent years is likely related to increased and earlier diagnosis. One can look at the trend to earlier diagnosis in two ways. The first is that many of these cancers are small and not likely to develop into aggressive malignancies. A second perspective is that earlier diagnosis removes these cancers at a time when they are not likely to have spread beyond the thyroid gland, thereby improving the long-term outcome for the patient. No consensus exists at present on whether this trend toward earlier diagnosis is beneficial or unnecessary.

The argument against early diagnosis and treatment is based on the logic that many small thyroid cancers (mostly papillary) will not grow or metastasize. This view holds the overwhelming majority of thyroid cancers are overdiagnosed that is, will never cause any symptoms, illness, or death for the patient, even if nothing is ever done about the cancer. Including these overdiagnosed cases skews the statistics by lumping clinically significant cases in with apparently harmless cancers.[39] Thyroid cancer is incredibly common, with autopsy studies of people dying from other causes showing that more than one-third of older adults technically have thyroid cancer, which is causing them no harm.[39] Detecting nodules that might be cancerous is easy, simply by feeling the throat, which contributes to the level of overdiagnosis. Benign (noncancerous) nodules frequently co-exist with thyroid cancer; sometimes, a benign nodule is discovered, but surgery uncovers an incidental small thyroid cancer. Increasingly, small thyroid nodules are discovered as incidental findings on imaging (CT scan, MRI, ultrasound) performed for another purpose; very few of these people with accidentally discovered, symptom-free thyroid cancers will ever have any symptoms, and treatment in such patients has the potential to cause harm to them, not to help them.[39][40]

Thyroid cancer is three times more common in women than in men, but according to European statistics,[41] the overall relative 5-year survival rate for thyroid cancer is 85% for females and 74% for males.[42]

The table below highlights some of the challenges with decision making and prognostication in thyroid cancer. While general agreement exists that stage I or II papillary, follicular, or medullary cancer have good prognoses, when evaluating a small thyroid cancer to determine which ones will grow and metastasize and which will not is not possible. As a result, once a diagnosis of thyroid cancer has been established (most commonly by a fine needle aspiration), a total thyroidectomy likely will be performed.

This drive to earlier diagnosis has also manifested itself on the European continent by the use of serum calcitonin measurements in patients with goiter to identify patients with early abnormalities of the parafollicular or calcitonin-producing cells within the thyroid gland. As multiple studies have demonstrated, the finding of an elevated serum calcitonin is associated with the finding of a medullary thyroid carcinoma in as high as 20% of cases.

In Europe where the threshold for thyroid surgery is lower than in the United States, an elaborate strategy that incorporates serum calcitonin measurements and stimulatory tests for calcitonin has been incorporated into the decision to perform a thyroidectomy; thyroid experts in the United States, looking at the same data, have for the most part not incorporated calcitonin testing as a routine part of their evaluations, thereby eliminating a large number of thyroidectomies and the consequent morbidity. The European thyroid community has focused on prevention of metastasis from small medullary thyroid carcinomas; the North American thyroid community has focused more on prevention of complications associated with thyroidectomy (see American Thyroid Association guidelines below). As demonstrated in the table below, individuals with stage III and IV disease have a significant risk of dying from thyroid cancer. While many present with widely metastatic disease, an equal number evolve over years and decades from stage I or II disease. Physicians who manage thyroid cancer of any stage recognize that a small percentage of patients with low-risk thyroid cancer will progress to metastatic disease.

Improvements have been made in thyroid cancer treatment during recent years. The identification of some of the molecular or DNA abnormalities has led to the development of therapies that target these molecular defects. The first of these agents to negotiate the approval process is vandetanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets the RET proto-oncogene, two subtypes of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and the epidermal growth factor receptor.[43] More of these compounds are under investigation and are likely to make it through the approval process. For differentiated thyroid carcinoma, strategies are evolving to use selected types of targeted therapy to increase radioactive iodine uptake in papillary thyroid carcinomas that have lost the ability to concentrate iodide. This strategy would make possible the use of radioactive iodine therapy to treat "resistant" thyroid cancers. Other targeted therapies are being evaluated, making life extension possible over the next 5–10 years for those with stage III and IV thyroid cancer.

Prognosis is better in younger people than older ones.[42]

Prognosis depends mainly on the type of cancer and cancer stage.

| Thyroid cancer type | 5-year survival | 10-year survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | Overall | Overall | |

| Papillary | 100%[44] | 100%[44] | 93%[44] | 51%[44] | 96%[45] or 97%[46] | 93%[45] |

| Follicular | 100%[44] | 100%[44] | 71%[44] | 50%[44] | 91%[45] | 85%[45] |

| Medullary | 100%[44] | 98%[44] | 81%[44] | 28%[44] | 80%,[45] 83%[47] or 86%[48] | 75%[45] |

| Anaplastic | (always stage IV)[44] | 7%[44] | 7%[44] or 14%[45] | (no data) | ||

Epidemiology

Thyroid cancer, in 2010, resulted in 36,000 deaths globally up from 24,000 in 1990.[49] Obesity may be associated with a higher incidence of thyroid cancer, but this relationship remains the subject of much debate.[50]

Thyroid cancer accounts for less than 1% of cancer cases and deaths in the UK. Around 2,700 people were diagnosed with thyroid cancer in the UK in 2011, and around 370 people died from the disease in 2012.[51]

Notable cases

References

- "Thyroid Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 27 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Carling, T.; Udelsman, R. (2014). "Thyroid Cancer". Annual Review of Medicine. 65: 125–37. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-061512-105739. PMID 24274180.

- "Thyroid Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 12 May 2017. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Cancer of the Thyroid - Cancer Stat Facts". seer.cancer.gov. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- "Cancer Fact sheet N°297". World Health Organization. February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- US Preventive Services Task, Force.; Bibbins-Domingo, K; Grossman, DC; Curry, SJ; Barry, MJ; Davidson, KW; Doubeni, CA; Epling JW, Jr; Kemper, AR; Krist, AH; Kurth, AE; Landefeld, CS; Mangione, CM; Phipps, MG; Silverstein, M; Simon, MA; Siu, AL; Tseng, CW (9 May 2017). "Screening for Thyroid Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 317 (18): 1882–1887. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.4011. PMID 28492905.

- World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.15. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- Hu MI, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Lustig R, Lamont JP. "Thyroid and Parathyroid Cancers" Archived 28 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. 11 ed. 2008.

- Durante, Cosimo; Grani, Giorgio; Lamartina, Livia; Filetti, Sebastiano; Mandel, Susan J.; Cooper, David S. (6 March 2018). "The Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Nodules". JAMA. 319 (9): 914–924. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0898. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 29509871.

- "Radioactive I-131 from Fallout". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- dos Santos Silva I, Swerdlow AJ (1993). "Thyroid cancer epidemiology in England and Wales: time trends and geographical distribution". Br J Cancer. 67 (2): 330–40. doi:10.1038/bjc.1993.61. PMC 1968194. PMID 8431362.

- "Experts link higher incidence of children's cancer to Fukushima radiation". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Pacini, F. (2012). "Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up". Annals of Oncology. 21: 214–19. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq190. PMID 20555084.

- "Genetics of Endocrine and Neuroendocrine Neoplasias". National Cancer Institute. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- Bennedbaek FN, Perrild H, Hegedüs L (1999). "Diagnosis and treatment of the solitary thyroid nodule. Results of a European survey". Clin. Endocrinol. 50 (3): 357–63. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00663.x. PMID 10435062.

- Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten; Grossman, David C.; Curry, Susan J.; Barry, Michael J.; Davidson, Karina W.; Doubeni, Chyke A.; Epling, John W.; Kemper, Alex R.; Krist, Alex H.; Kurth, Ann E.; Landefeld, C. Seth; Mangione, Carol M.; Phipps, Maureen G.; Silverstein, Michael; Simon, Melissa A.; Siu, Albert L.; Tseng, Chien-Wen (9 May 2017). "Screening for Thyroid Cancer". JAMA. 317 (18): 1882–1887. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.4011. PMID 28492905.

- "Thyroid Cancer Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 1 January 1980. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- "Thyroid cancer". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- Chapter 20 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1. 8th edition.

- Grani, Giorgio; Lamartina, Livia; Durante, Cosimo; Filetti, Sebastiano; Cooper, David S (November 2017). "Follicular thyroid cancer and Hürthle cell carcinoma: challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical management". The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 6 (6): 500–514. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30325-X. PMID 29102432.

- Schlumberger M, Carlomagno F, Baudin E, Bidart JM, Santoro M (2008). "New therapeutic approaches to treat medullary thyroid carcinoma". Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 4 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1038/ncpendmet0717. PMID 18084343.

- Nix P, Nicolaides A, Coatesworth AP (2005). "Thyroid cancer review 2: management of differentiated thyroid cancers". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 59 (12): 1459–63. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00672.x. PMID 16351679. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013.

- Nix PA, Nicolaides A, Coatesworth AP (2006). "Thyroid cancer review 3: management of medullary and undifferentiated thyroid cancer". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 60 (1): 80–84. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00673.x. PMID 16409432.

- Shaha AR (2007). "TNM classification of thyroid carcinoma". World J Surg. 31 (5): 879–87. doi:10.1007/s00268-006-0864-0. PMID 17308849.

- Dideban, S; Abdollahi, A; Meysamie, A; Sedghi, S; Shahriari, M (2016). "Thyroid Papillary Microcarcinoma: Etiology, Clinical Manifestations,Diagnosis, Follow-up, Histopathology and Prognosis". Iranian Journal of Pathology. 11 (1): 1–19. PMC 4749190. PMID 26870138.

- Hughes, DT; Haymart, MR; Miller, BS; Gauger, PG; Doherty, GM (March 2011). "The most commonly occurring papillary thyroid cancer in the United States is now a microcarcinoma in a patient older than 45 years". Thyroid. 21 (3): 231–6. doi:10.1089/thy.2010.0137. hdl:2027.42/90466. PMID 21268762.

- Woolner LL, Lemmon ML, Beahrs OH, Black BM, Keating FR (1960). "Occult papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland: a study of 140 cases observed in a 30-year period". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 20: 89–105. doi:10.1210/jcem-20-1-89. PMID 13845950.

- Hindié E, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Keller I, Duron F, Devaux JY, Calzada-Nocaudie M, Sarfati E, Moretti JL, Bouchard P, Toubert ME (2007). "Bone metastases of differentiated thyroid cancer: Impact of early 131I-based detection on outcome". Endocrine-Related Cancer. 14 (3): 799–807. doi:10.1677/ERC-07-0120. PMID 17914109.

- Schlumberger M, Arcangioli O, Piekarski JD, Tubiana M, Parmentier C (1988). "Detection and treatment of lung metastases of differentiated thyroid carcinoma in patients with normal chest X-rays". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 29 (11): 1790–94. PMID 3183748.

- Das, Somen (2008). A concise textbook of surgery (5th. ed.). Calcutta: Dr S. Das. ISBN 978-8190568128.

- Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, Hauger BR, Kloos RT, Lee SL, Mandel SJ, Mazzaferri EL, McIver B, Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Sherman SI, Steward DL, Tuttle RM (2009). "Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer" (PDF). Thyroid. 19 (11): 1167–214. doi:10.1089/thy.2009.0110. hdl:2027.42/78131. PMID 19860577.

- British Thyroid Association, Royal College of Physicians, Perros P (2007). Guidelines for the management of thyroid cancer. 2nd edition. Report of the Thyroid Cancer Guidelines Update Group (PDF). Royal College of Physicians. p. 16. ISBN 9781860163098. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Welch, H. Gilbert; Schwartz, Lisa; M.D., Lisa M. Schwartz; Steve Woloshin (18 January 2011). Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. Beacon Press. pp. 138–43. ISBN 9780807022009. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- Perros, Petros; Boelaert, Kristien; Colley, Steve; Evans, Carol; Evans, Rhodri M; Gerrard BA, Georgina; Gilbert, Jackie; Harrison, Barney; Johnson, Sarah J; Giles, Thomas E; Moss, Laura; Lewington, Val; Newbold, Kate; Taylor, Judith; Thakker, Rajesh V; Watkinson, John; Williams, Graham R. (July 2014). "Guidelines for the management of thyroid cancer". Clinical Endocrinology. 81: 1–122. doi:10.1111/cen.12515. PMID 24989897.

- Lamartina, Livia; Grani, Giorgio; Durante, Cosimo; Filetti, Sebastiano (18 January 2018). "Recent advances in managing differentiated thyroid cancer". F1000Research. 7: 86. doi:10.12688/f1000research.12811.1. PMC 5773927. PMID 29399330.

- Welch, H. Gilbert; Woloshin, Steve; Schwartz, Lisa A. (2011). Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. [Malaysia?]: Beacon Press. pp. 61–34. ISBN 978-0-8070-2200-9.

- Hofman MS (2013). "Thyroid nodules: Time to stop over-reporting normal findings and update consensus guidelines". BMJ. 347: f5742. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5742. PMID 24068719.

- "Thyroid Cancer". MedicineNet.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Numbers from EUROCARE, from Page 10 Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine in: F. Grünwald; Biersack, H. J.; Grںunwald, F. (2005). Thyroid cancer. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-22309-2.

- "FDA approves new treatment for rare form of thyroid cancer" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- cancer.org Thyroid Cancer Archived 18 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine By the American Cancer Society. In turn citing: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th ed).

- Numbers from National Cancer Database in the US, from Page 10 Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine in: F. Grünwald; Biersack, H. J.; Grunwald, F. (2005). Thyroid cancer. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-22309-2. (Note:Book also states that the 14% 10-year survival for anaplastic thyroid cancer was overestimated)

- Rounded up to nearest natural number from 96.7% as given by eMedicine Thyroid, Papillary Carcinoma Archived 28 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Author: Luigi Santacroce. Coauthors: Silvia Gagliardi and Andrew Scott Kennedy. Updated: 28 September 2010

- By 100% minus cause-specific mortality of 17% at 5 yr, as given by Barbet J, Campion L, Kraeber-Bodéré F, Chatal JF (2005). "Prognostic Impact of Serum Calcitonin and Carcinoembryonic Antigen Doubling-Times in Patients with Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 90 (11): 6077–84. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0044. PMID 16091497.

- "Medullary Thyroid Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 4 February 2016. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604.

- Santini F, Marzullo P, Rotondi M, Ceccarini G, Pagano L, Ippolito S, Chiovato L, Biondi B (October 2014). "Mechanisms in Endocrinology: The crosstalk between thyroid gland and adipose tissue: signal integration in health and disease". Eur J Endocrinol. 171 (4): R137–52. doi:10.1530/eje-14-0067. PMID 25214234. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014.

- "Thyroid cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- "Celebrities with Thyroid problems". Alexander Shifrin. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Bamberger, Michael (27 May 2002). "Survivors". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Lane, Charles (8 September 2005). "Rehnquist Eulogies Look Beyond Bench". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thyroid cancer. |

- Thyroid cancer at Curlie

- Management Guidelines for Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Taskforce (2015).