Thumb

The thumb is the first digit (finger) of the hand. Although your thumb is not actually a finger, people still classify it as one. When a person is standing in the medical anatomical position (where the palm is facing to the front), the thumb is the outermost digit. The Medical Latin English noun for thumb is pollex (compare hallux for big toe), and the corresponding adjective for thumb is pollical.

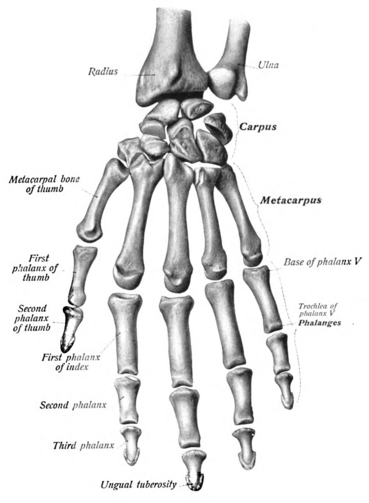

| Thumb | |

|---|---|

Bones of the thumb, visible at far left | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Princeps pollicis artery |

| Vein | Dorsal venous network of hand |

| Nerve | Dorsal digital nerves of radial nerve, proper palmar digital nerves of median nerve |

| Lymph | Infraclavicular lymph nodes[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pollex digitus I manus digitus primus manus |

| MeSH | D013933 |

| TA | A01.1.00.053 |

| FMA | 24938 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Definition

Thumb and finger

The English word "finger" has two senses, even in the context of appendages of a single typical human hand:

- Any of the four terminal members of the hand, specifically those other than the thumb.

- Any of the five digits.

Linguistically, it appears that the original sense was the broader of these two: penkwe-ros (also rendered as penqrós) was, in the inferred Proto-Indo-European language, a suffixed form of penkwe (or penqe), which has given rise to many Indo-European-family words (tens of them defined in English dictionaries) that involve or flow from concepts of fiveness.

The thumb shares the following with each of the other four fingers:

- Having a skeleton of phalanges, joined by hinge-like joints that provide flexion toward the palm of the hand

- Having a dorsal surface that features hair and a nail, and a hairless palmar aspect with fingerprint ridges

The thumb contrasts with each of the other four by being the only digit that:

- Is opposable to the other four fingers

- Has two phalanges rather than three

- Has greater breadth in the distal phalanx than in the proximal phalanx

- Is attached to such a mobile metacarpus (which produces most of the opposability)

and hence the etymology of the word: "tum" is Proto-Indo-European for "swelling" (cf "tumour" and "thigh") since the thumb is the stoutest of the fingers.

Opposition and apposition

In humans, opposition and apposition are two movements unique to the thumb, but these words are not synonyms:

Primatologists and hand research pioneers John and Prudence Napier defined opposition as: "A movement by which the pulp surface of the thumb is placed squarely in contact with – or diametrically opposite to – the terminal pads of one or all of the remaining digits." For this true, pulp-to-pulp opposition to be possible, the thumb must rotate about its long axis (at the carpometacarpal joint).[3] Arguably, this definition was chosen to underline what is unique to the human thumb.

Anatomists and other researchers focused exclusively on human anatomy, on the other hand, tend to elaborate this definition in various ways and, consequently, there are hundreds of definitions.[4] Some anatomists[5] restrict opposition to when the thumb is approximated to the fifth digit (little finger) and refer to other approximations between the thumb and other digits as apposition. To anatomists, this makes sense as two intrinsic hand muscles are named for this specific movement (the opponens pollicis and opponens digiti minimi respectively).

Other researchers use another definition,[4] referring to opposition-apposition as the transition between flexion-abduction and extension-adduction; the side of the distal thumb phalanx thus approximated to the palm or the hand's radial side (side of index finger) during apposition and the pulp or "palmar" side of the distal thumb phalanx approximated to either the palm or other digits during opposition.

Moving a limb back to its neutral position is called reposition and a rotary movement is referred to as circumduction.

Human anatomy

Skeleton

The skeleton of the thumb consists of the first metacarpal bone which articulates proximally with the carpus at the carpometacarpal joint and distally with the proximal phalanx at the metacarpophalangeal joint. This latter bone articulates with the distal phalanx at the interphalangeal joint. Additionally, there are two sesamoid bones at the metacarpophalangeal joint.

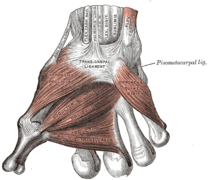

Muscles

The muscles of the thumb can be compared to guy-wires supporting a flagpole; tension from these muscular guy-wires must be provided in all directions to maintain stability in the articulated column formed by the bones of the thumb. Because this stability is actively maintained by muscles rather than by articular constraints, most muscles attached to the thumb tend to be active during most thumb motions.[6]

The muscles acting on the thumb can be divided into two groups: The extrinsic hand muscles, with their muscle bellies located in the forearm, and the intrinsic hand muscles, with their muscle bellies located in the hand proper.[7]

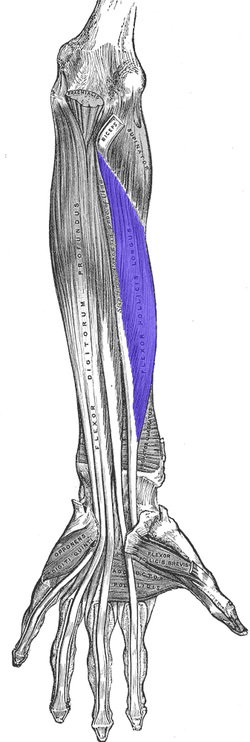

Extrinsic

A ventral forearm muscle, the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) originates on the anterior side of the radius distal to the radial tuberosity and from the interosseous membrane. It passes through the carpal tunnel in a separate tendon sheath, after which it lies between the heads of the flexor pollicis brevis. It finally attaches onto the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb. It is innervated by the anterior interosseus branch of the median nerve (C7-C8)[8] It is a persistence of one of the former contrahentes muscles that pulled the fingers or toes together.

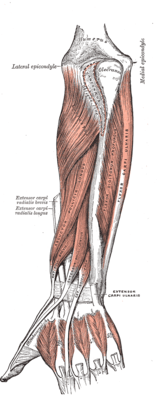

Three dorsal forearm muscles act on the thumb:

The abductor pollicis longus (APL) originates on the dorsal sides of both the ulna and the radius, and from the interosseous membrane. Passing through the first tendon compartment, it inserts to the base of the first metacarpal bone. A part of the tendon reaches the trapezium, while another fuses with the tendons of the extensor pollicis brevis and the abductor pollicis brevis. Except for abducting the hand, it flexes the hand towards the palm and abducts it radially. It is innervated by the deep branch of the radial nerve (C7-C8).[9]

The extensor pollicis longus (EPL) originates on the dorsal side of the ulna and the interosseous membrane. Passing through the third tendon compartment, it is inserted onto the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb. It uses the dorsal tubercle on the lower extremity of the radius as a fulcrum to extend the thumb and also dorsiflexes and abducts the hand at the wrist. It is innervated by the deep branch of the radial nerve (C7-C8).[9]

The extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) originates on the ulna distal to the abductor pollicis longus, from the interosseus membrane, and from the dorsal side of the radius. Passing through the first tendon compartment together with the abductor pollicis longus, it is attached to the base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. It extends the thumb and, because of its close relationship to the long abductor, also abducts the thumb. It is innervated by the deep branch of the radial nerve (C7-T1).[9]

The tendons of the extensor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis form what is known as the anatomical snuff box (an indentation on the lateral aspect of the thumb at its base) The radial artery can be palpated anteriorly at the wrist(not in the snuffbox).

Intrinsic

There are three thenar muscles:

The abductor pollicis brevis (APB) originates on the scaphoid tubercle and the flexor retinaculum. It inserts to the radial sesamoid bone and the proximal phalanx of the thumb. It is innervated by the median nerve (C8-T1).[10]

The flexor pollicis brevis (FPB) has two heads. The superficial head arises on the flexor retinaculum, while the deep head originates on three carpal bones: the trapezium, trapezoid, and capitate. The muscle is inserted onto the radial sesamoid bone of the metacarpophalangeal joint. It acts to flex, adduct, and abduct the thumb, and is therefore also able to oppose the thumb. The superficial head is innervated by the median nerve, while the deep head is innervated by the ulnar nerve (C8-T1).[10]

The opponens pollicis originates on the tubercle of the trapezium and the flexor retinaculum. It is inserted onto the radial side of the first metacarpal. It opposes the thumb and assists in adduction. It is innervated by the median nerve.[10]

Other muscles involved are:

The adductor pollicis also has two heads. The transversal head originates along the entire third metacarpal bone, while the oblique head originates on the carpal bones proximal to the third metacarpal. The muscle is inserted onto the ulnar sesamoid bone of the metacarpophalangeal joint. It adducts the thumb, and assists in opposition and flexion. It is innervated by the deep branch of the ulnar nerve (C8-T1).[10]

The first dorsal interosseous, one of the central muscles of the hand, extends from the base of the thumb metacarpal to the radial side of the proximal phalanx of the index finger.[11]

Variations

There is a variation of the human thumb where the angle between the first and second phalanges varies between 0° and almost 90° when the thumb is in a thumbs-up gesture.[12]

It has been suggested that the variation is an autosomal recessive trait, called a "Hitchhiker's thumb", with homozygous carriers having an angle close to 90°.[13] However this theory has been disputed, since the variation in thumb angle is known to fall on a continuum and shows little evidence of the bi-modality seen in other recessive genetic traits.[12]

Other formations of the thumb include a triphalangeal thumb and polydactyly.

Grips

Right: Cricketer Jack Iverson's "bent finger grip", an unusual pad-to-side precision grip designed to confuse batsmen.

One of the earlier significant contributors to the study of hand grips was orthopedic primatologist and paleoanthropologist John Napier, who proposed organizing the movements of the hand by their anatomical basis as opposed to work done earlier that had only used arbitrary classification.[14] Most of this early work on hand grips had a pragmatic basis as it was intended to narrowly define compensable injuries to the hand, which required an understanding of the anatomical basis of hand movement. Napier proposed two primary prehensile grips: the precision grip and the power grip.[15] The precision and power grip are defined by the position of the thumb and fingers where:

- The power grip is when the fingers (and sometimes palm) clamp down on an object with the thumb making counter pressure. Examples of the power grip are gripping a hammer, opening a jar using both your palm and fingers, and during pullups.

- The precision grip is when the intermediate and distal phalanges ("fingertips") and the thumb press against each other. Examples of a precision grip are writing with a pencil, opening a jar with the fingertips alone, and gripping a ball (only if the ball is not tight against the palm).

Opposability of the thumb should not be confused with a precision grip as some animals possess semi-opposable thumbs yet are known to have extensive precision grips (Tufted Capuchins for example).[17] Nevertheless, precision grips are usually only found in higher apes, and only in degrees significantly more restricted than in humans.[18]

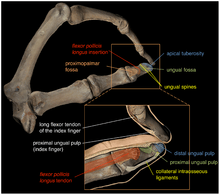

The pad-to-pad pinch between the thumb and index finger is made possible because of the human ability to passively hyperextend the distal phalanx of the index finger. Most non-human primates have to flex their long fingers in order for the small thumb to reach them.[19]

In humans, the distal pads are wider than in other primates because the soft tissues of the finger tip are attached to a horseshoe-shaped edge on the underlying bone, and, in the grasping hand, the distal pads can therefore conform to uneven surfaces while pressure is distributed more evenly in the finger tips. The distal pad of the human thumb is divided into a proximal and a distal compartment, the former more deformable than the latter, which allows the thumb pad to mold around an object.[19]

In robotics, almost all robotic hands have a long and strong opposable thumb. Like human hands, the thumb of a robotic hand also plays a key role in gripping an object. One inspiring approach of robotic grip planning is to mimic human thumb placement. [20] In a sense, human thumb placement indicates which surface or part of the object is good for grip. Then the robot places its thumb to the same location and plans the other fingers based on the thumb placement.

The function of the thumb declines physiologically with aging. This can be demonstrated by assessing the motor sequencing of the thumb.[21]

Evolution

A primitive autonomization of the first carpometacarpal joint (CMC) may have occurred in dinosaurs. A real differentiation appeared perhaps 70 mya in early primates, while the shape of the human thumb CMC finally appears about 5 mya. The result of this evolutionary process is a human CMC joint positioned at 80° of pronation, 40 of abduction, and 50° of flexion in relation to an axis passing through the second and third CMC joints.[22]

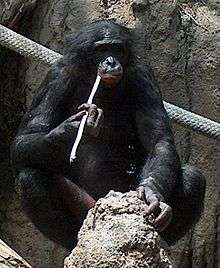

Opposable thumbs are shared by some primates, including most catarrhines. The climbing and suspensory behaviour in orthograde apes, such as chimpanzees, has resulted in elongated hands while the thumb has remained short. As a result, these primates are unable to perform the pad-to-pad grip associated with opposability. However, in pronograde monkeys such as baboons, an adaptation to a terrestrial lifestyle has led to reduced digit length and thus hand proportions similar to those of humans. Consequently, these primates have dexterous hands and are able to grasp objects using a pad-to-pad grip. It can thus be difficult to identify hand adaptations to manipulation-related tasks based solely on thumb proportions.[23]

The evolution of the fully opposable thumb is usually associated with Homo habilis, a forerunner of Homo sapiens.[24] This, however, is the suggested result of evolution from Homo erectus (around 1 mya) via a series of intermediate anthropoid stages, and is therefore a much more complicated link.

Modern humans are unique in the musculature of their forearm and hand. Yet, they remain autapomorphic, meaning each muscle is found in one or more non-human primates. The extensor pollicis brevis and flexor pollicis longus allow modern humans to have great manipulative skills and strong flexion in the thumb.[25]

However, a more likely scenario may be that the specialized precision gripping hand (equipped with opposable thumb) of Homo habilis preceded walking, with the specialized adaptation of the spine, pelvis, and lower extremities preceding a more advanced hand. And, it is logical that a conservative, highly functional adaptation be followed by a series of more complex ones that complement it. With Homo habilis, an advanced grasping-capable hand was accompanied by facultative bipedalism, possibly implying, assuming a co-opted evolutionary relationship exists, that the latter resulted from the former as obligate bipedalism was yet to follow.[26] Walking may have been a by-product of busy hands and not vice versa.

HACNS1 (also known as Human Accelerated Region 2) is a gene enhancer "that may have contributed to the evolution of the uniquely opposable human thumb, and possibly also modifications in the ankle or foot that allow humans to walk on two legs". Evidence to date shows that of the 110,000 gene enhancer sequences identified in the human genome, HACNS1 has undergone the most change during the human evolution since the chimpanzee-human last common ancestor.[27]

Other animals with opposable digits

Primates

- Primates fall into one of four groups:[28]

- Nonopposable thumbs: tarsiers and marmosets

- Pseudo-opposable thumbs: all strepsirrhines and Cebidae

- Opposable thumbs: Old World monkeys and all great apes

- Opposable with comparatively long thumbs: gibbons (or lesser apes)

The thumb is not opposable in all primates — some primates, such as the spider monkey and colobus, are virtually thumbless. The spider monkey compensates for this by using the hairless part of its long, prehensile tail for grabbing objects. In apes and Old World monkeys, the thumb can be rotated around its axis, but the extensive area of contact between the pulps of the thumb and index finger is a human characteristic.[19]

Darwinius masillae, an Eocene primate transitional fossil between prosimian and simian, had hands and feet with highly flexible digits featuring opposable thumbs and halluces.[29]

Other placental mammals

- Giant pandas — five clawed fingers plus an extra-long sesamoid bone beside the true first digit that, though not a true digit, works like an opposable thumb.[30]

- In some Muridae the hallux is clawless and fully opposable, including arboreal species such as Hapalomys, Chiropodomys, Vandeleuria, and Chiromyscus; and saltatorial, bipedal species such as Notomys and possibly some Gerbillinae.[31]

- The East African maned rat (Lophiomys imhausi), an arboreal, porcupine-like rodent, has four digits on its hands and feet and a partially opposable thumb.[32]

Additionally, in many polydactyl cats, both the innermost and outermost ("pinky") toes may become opposable, allowing the cat to perform more complex tasks.

Marsupials

Right: Opposable thumb on rear foot of an opossum

- In most phalangerid marsupials (a family of possums) except species Trichosurus and Wyulda the first and second digits of the forefoot are opposable to the other three. In the hind foot, the first toe is clawless but opposable and provides firm grip on branches. The second and third toes are partly syndactylous, united by skin at the top joint while the two separate nails serve as hair combs. The fourth and fifth digits are the largest of the hind foot.[33]

- Similar to phalangerids though in a different order, koalas have five digits on their fore and hind feet with sharp curved claws except for the first digit of the hind foot. The first and second digits of the forefeet are opposable to the other three, which enables the koala to grip smaller branches and search for fresh leaves in the outer canopy. Similar to the phalangerids, the second and third digits of the hind foot are fused but have separate claws.[34]

- Opossums are New World marsupials with opposable thumbs in the hind feet giving these animals their characteristic grasping capability (with the exception of the water opossum, the webbed feet of which restrict opposability).[35]

- The mouse-like microbiotheres were a group of South American marsupials most closely related to Australian marsupials. The only extant member, Dromiciops gliroides, is not closely related to opossums but has paws similar to these animals, each having opposable toes adapted for gripping.[36]

Dinosaurs

- The bird-like dinosaur Troodon had a partially opposable finger. It is possible that this adaptation was used to better manipulate ground objects or moving undergrowth branches when searching for prey.[37]

- The small predatory dinosaur Bambiraptor may have had mutually opposable first and third fingers and a forelimb maneouverability that would allow the hand to reach its mouth. Its forelimb morphology and range of motion enabled two-handed prehension, one-handed clutching of objects to the chest, and use of the hand as a hook.[38]

- Nqwebasaurus — a coelurosaur with a long, three-fingered hand which included a partially opposable thumb (a "killer claw").[39]

In addition to these, some other dinosaurs may have had partially or completely opposed digits in order to manipulate food and/or grasp prey.

Birds

- Most birds have at least one opposable digit on the foot, in various configurations, but these are seldom called "thumbs". They are more often known simply as halluxes.

Amphibians

- Phyllomedusa, a genus of frogs native to South America.[40]

See also

- Prehensility

- Thumb signal

- Thumb twiddling

- Thumb war

- Pollicization

Notes

- clinicalconsiderations at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- "The Thumb is the Hero". The New York Times. January 11, 1981. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

The "fishing rod" a chimp strips of leaves and pokes into a termite nest to bring up a snack is as far as he'll ever get toward orbiting the planets.

- "Primates FAQ: Do any primates have opposable thumbs?". Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- van Nierop et al. 2008, p. 34

- Brown et al. 2004

- Austin 2005, p. 339

- "Muscles of the thumb". Eaton hand. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- Platzer 2004, p. 162

- Platzer 2004, p. 168

- Platzer 2004, p. 176

- Platzer 2004, p. 174

- "Myth's of Human Genetics: Hitchhiker's Thumb". Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- "Thumb, Distal Hyperextensibility of". OMIM. NCBI. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Slocum & Pratt 1946, McBride 1942, p. 631

- Napier 1956, pp. 902–913

- Almécija, Moyà-Solà & Alba 2010

- Costello & Fragaszy 1988, pp. 235–245

- Young 2003, pp. 165–174, Christel, Kitzel & Niemitz 2004, pp. 165–194, Byrne & Byrne 1993, p. 241

- Jones & Lederman 2006, Evolutionary Development and Anatomy of the Hand, p. 12

- Lin, Yun; Sun, Yu (2015). "Robot grasp planning based on demonstrated grasp strategies". The International Journal of Robotics Research. 34: 26–42. doi:10.1177/0278364914555544.

- Bodranghien, Florian; Mahé, Helene; Baude, Benjamin; Manto, Mario U.; Busegnies, Yves; Camut, Stéphane; Habas, Christophe; Marien, Peter; de Marco, Giovanni (2017-05-10). "The Click Test: A Novel Tool to Quantify the Age-Related Decline of Fast Motor Sequencing of the Thumb". Current Aging Science. 10 (4): 305–318. doi:10.2174/1874609810666170511100318. ISSN 1874-6128. PMID 28494715.

- Brunelli 1999, p. 167

- Moyà-Solà, Köhler & Rook 1999, pp. 315–6

- Leakey, Tobias & Napier 1964: "[In Homo habilis] the pollex is well developed and fully opposable and the hand is capable not only of a power grip but of, at least, a simple and usually well developed precision grip."

- Diogo, R.; Richmond, B. G.; Wood, B. (2012). "Evolution and homologies of primate and modern human hand and forearm muscles, with notes on thumb movements and tool use". Journal of Human Evolution. 63 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.04.001. PMID 22640954.

- Harcourt-Smith & Aiello 2004

- "HACNS1: Gene enhancer in evolution of human opposable thumb". Science Codex. September 4, 2008. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- Ankel-Simons 2007, p. 345

- Franzen et al. 2009, pp. 15–18

- "The Panda's Thumb". Athro. 2000. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Ellerman 1941, p. 2

- Grzimek, Bernhard (2003). Hutchins, Michael; Kleiman, Devra G.; Geist, Valerius; et al. (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, Vol 16, Mammals V (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-7876-7750-3.

- Nowak 1999, p. 89

- McDade 2003, vol 13, p. 44

- McDade 2003, vol 12, p. 250

- McDade 2003, vol 12, p. 274

- "Troodon". Prehistoric Wildlife. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Senter 2006

- de Klerk et al. 2000, p. 327. The left manus shows that the flexed digit I had the potential to partially oppose digits II and III.

- Bertoluci, Jaime (18 December 2002). "Phyllomedusa". Journal of Herpetology. 1 (2): 93. doi:10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v1i2p93-95.

References

- Almécija, S.; Moyà-Solà, S.; Alba, D. M. (2010). "Early Origin for Human-Like Precision Grasping: A Comparative Study of Pollical Distal Phalanges in Fossil Hominins". PLoS ONE. 5 (7): e11727. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511727A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011727. PMC 2908684. PMID 20661444.

- Ankel-Simons, Friderun (2007). "Chapter 8: Postcranial Skeleton". Primate Anatomy (3rd ed.). Academic Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-12-372576-9.

- Austin, Noelle M. (2005). "Chapter 9: The Wrist and Hand Complex". In Levangie, Pamela K.; Norkin, Cynthia C. (eds.). Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (4th ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-1191-7.

- Brown, David P.; Freeman, Eric D.; Cuccurullo, Sara; Freeman, Ted L. (2004). "Upper Extremities—Hand Region: Range of Motion of the Digits". In Cuccurullo, Sara (ed.). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-888799-45-3. (NCBI)

- Brunelli, Giovanni R. (1999). "Stability in the first carpometacarpal joint". In Brüser, Peter; Gilbert, Alain (eds.). Finger bone and joint injuries. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-85317-690-6.

- Byrne, R.W.; Byrne, J.M.E. (1993). "Complex Leaf-Gathering Skills of Mountain Gorillas (Gorilla g. beringei): Variability and Standardization" (PDF). American Journal of Primatology. 31 (4): 241–261. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350310402. ISSN 0275-2565. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2009.

- Christel, Marianne I.; Kitzel, Stefanie; Niemitz, Carsten (30 November 2004). "How Precisely do Bonobos (Pan paniscus) Grasp Small Objects?". International Journal of Primatology. 19 (1): 165–194. doi:10.1023/A:1020319313219.

- Costello, Michael B.; Fragaszy, Dorothy M. (March 1988). "Prehension in Cebus and Saimiri: I. Grip type and hand preference". American Journal of Primatology. 15 (3): 235–245. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350150306.

- de Klerk, W.J.; Forster, C.A.; Sampson, S.D.; Chinsamy, A.; Ross, C.F. (2000). "A new coelurosaurian dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of South Africa" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (2): 324–332. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0324:ancdft]2.0.co;2.

- Diogo, R; Richmond, BG; Wood, B (2012). "Evolution and homologies of primate and modern human hand and forearm muscles, with notes on thumb movements and tool use". Journal of Human Evolution. 63 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.04.001. PMID 22640954.

- Ellerman, John Reeves (1941). The families and genera of living rodents. Vol. II. Family Muridae. London: British Museum (Natural History).

- Franzen, JL; Gingerich, PD; Habersetzer, J; Hurum, JH; von Koenigswald, W; et al. (2009). Hawks, John (ed.). "Complete Primate Skeleton from the Middle Eocene of Messel in Germany: Morphology and Paleobiology". PLoS ONE. 4 (5): e5723. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5723F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005723. PMC 2683573. PMID 19492084.

- Harcourt-Smith, W E H; Aiello, L C (May 2004). "Fossils, feet and the evolution of human bipedal locomotion". Journal of Anatomy. 204 (5): 403–16. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00296.x. PMC 1571304. PMID 15198703.

- Hsu, Ar-Tyan; Meng-Tsu Hu; Fong Ching Su (July 2008). "Effect of Gender, Flexibility and Thumb Type on Thumb Tip Generation". Journal of Biomechanics. 41 (Supplement 1): S148. doi:10.1016/S0021-9290(08)70148-9.

- Jones, Lynette A.; Lederman, Susan J. (2006). Human hand function. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 9780195173154.

- Leakey, LSB; Tobias, PV; Napier, JR (April 1964). "A New Species of Genus Homo from Olduvai Gorge" (PDF). Nature. 202 (4927): 7–9. Bibcode:1964Natur.202....7L. doi:10.1038/202007a0. PMID 14166722.

- McBride, Earl Duwain (1942). Disability evaluation: principles of treatment of compensable injuries. Lippincott. p. 631.

- McDade, Melissa C. (2003). "Koalas (Phascolartidae)". In Hutchins, Michael; Kleiman, Devra G.; Geist, Valerius; et al. (eds.). Grzimek's animal life encyclopedia: Volumes 12–16, Mammals I–V (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

- Moyà-Solà, Salvador; Köhler, Meike; Rook, Lorenzo (January 5, 1999). "Evidence of hominid-like precision grip capability in the hand of the Miocene ape Oreopithecus" (PDF). PNAS. 96 (1): 313–317. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96..313M. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.1.313. PMC 15136. PMID 9874815.

- Napier, John Russell (November 1956). "The prehensile movements of the human hand" (PDF). J Bone Joint Surg Br. 38 (4): 902–913. PMID 13376678.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's mammals of the world, Volume 2 (6th ed.). JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Senter, Phil (2006). "Comparison of forelimb function between Deinonychus and Bambiraptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 897–906. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[897:COFFBD]2.0.CO;2.

- Slocum, D.B.; Pratt, D.R. (1946). "Disability Evaluation for the Hand" (PDF). Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 28 (3): 491.

- van Nierop, Onno A.; van der Helm, Aadjan; Overbeeke, Kees J.; Djajadiningrat, Tom J.P. (2008). "A natural human hand model" (PDF). Visual Comput. 24 (1): 31–44. doi:10.1007/s00371-007-0176-x.

- Young, Richard W. (January 2003). "Evolution of the human hand: the role of throwing and clubbing". Journal of Anatomy. 202 (1): 165–174. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00144.x. PMC 1571064. PMID 12587931.