Thermal burn

A thermal burn is a type of burn resulting from making contact with heated objects, such as boiling water, steam, hot cooking oil, fire, and hot objects. Scalds are the most common type of thermal burn suffered by children, but for adults thermal burns are most commonly caused by fire.[2] Burns are generally classified from first degree up to fourth degree, but the American Burn Association (ABA) has categorized thermal burns as minor, moderate, and major, based almost solely on the depth and size of the burn.[3]

Causes

Hot liquids and steam

Scalding is a type of thermal burn caused by boiling water and steam, commonly suffered by children. Scalds are commonly caused by accidental spilling of hot liquids, having water temperature too high for baths and showers, steam from boiling water or heated food, or getting splattered by hot cooking oil.[4] Scalding is usually a first- or second-degree burn, and third-degree burn can sometimes result from prolonged contact.[5] Nearly three quarters of all burn injuries suffered by young children is scalding.[6]

Fire

Fire causes about 50% of all cases of thermal burns in the United States.[7] The most frequent event where people get burned by fire is during house fires encountered by firefighters and trapped occupants,[8] where 85% of all fire deaths take place.[9] Fireworks are another notable cause of fire burns, especially by adolescent males on Independence Days.[6] The most common cause of injury by fire or flame by children is touching candle flame. In some regions, such as the western United States, getting burned by wildfires are common, especially by firefighters who are trying to fight forest fires. Wildfires can suddenly shift due to changing wind directions, making it harder for firefighters and eyewitnesses to avoid getting burned.

If clothing the person wears catches fire, third-degree burn can develop in the matter of just few seconds.[10]

Hot objects

Solid objects that are hot can also cause contact burns, especially by children who intentionally touch things that they are unaware are too hot to touch.[11] Such burns imprinted on the skin usually form a pattern that resembles the object. Sources of burns from solid objects include ashes and coal, irons, soldering equipment, frying pans and pots, oven containers, light bulbs, and exhaust pipes.[12]

Pathophysiology

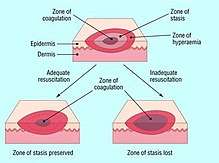

There are three (or sometimes four) degrees of burns, in ascending order of severity and depth. For more info, see Burn#Signs and symptoms. According to Jackson's thermal wound theory, there are three zones of major burn injury.

- Zone of coagulation is the area that sustained maximum damage from the heat source. Proteins become denaturated, and cell death is imminent due to destruction of blood vessels, resulting in ischemia to the area. Injury at this area is irreversible (coagulative necrosis & gangrene) [13]

- Zone of stasis surrounds the coagulation area, where tissue is potentially salvageable. This is the main area of focus when treating burn injuries.[13]

- Zone of hyperemia is the area surrounding the zone of stasis. Perfusion is adequate due to patent blood vessels, and erythema occurs due to increased vascular permeability.[14][13]

Factors

The minimum temperature that can cause a burn in a finite amount of time is 44 °C (111 °F) for exposure times exceeding 6 hours. From 44° to 51 °C (111° to 124 °F), the rate of burn approximately doubles with each degree risen. The burn would develop in less than a second if the exposure temperature is at least 70 °C (160 °F).[14]

There are skin factors that offer resistance to burns. A person who is more burn resistant would require higher temperature and longer exposure to burn as badly than a less resistant person.

Thick skin is more prone to superficial burns because of the simple fact that there's more to burn before it gets deep. Skin thickness varies throughout the body, from 0.5mm of the eye lids to 6mm in the soles of the feet. Skin thickness overall varies with age, being thinner at extremes of age.

External factors on the skin like hair, moisture or oils can also help ease and delay the burn. Another factor is skin circulation, which is used to dissipate heat imprinted on the skin.[14]

Prevention

Education is an important tool for children on how to prevent getting burned by fire or getting scalded. In that act, firefighters and community leaders are often employed in schools and clinics.[9]

Smoke alarms installed in homes are used to reduce deaths resulting from fire by half. Homeowners should change batteries at least once a year and replace smoke alarms every decade. Before fire occurs, a family should practice evacuating home, and when fire occurs the family must leave the residence immediately (within two minutes). To prevent house fires, a family should keep flammable objects, like matches, out of children's reach, and they must not leave anything involving flames unattended while keeping objects that can catch fire away from it by at least 12 inches, like stove ovens, stovetops, space heaters, and candles. Fire extinguishers should be stored in the kitchen, where most house fires start.[15]

To prevent children from getting burned, water temperature must not be set too high when taking baths or washing hands, nonflammable sleepwear should be worn, backburners should be used when cooking something on the stove, and hot foods, drinks, and irons should be kept away from the edge of counter and table.[16] Oven mitts and potholders must be used in handling hot containers. Care should be taken when taking hot foods out of microwave ovens, and covers should be opened gently to reduce the risk of steam burns.[17]

Treatment

The most important first action is to stop the burning process. The source of the burn should promptly be removed (or the patient removed from the source). If the person is on fire, he/she must be told to stop, drop and roll, or extinguish the fire by covering them with heavy blanket, wool, coat, or rug. Burning clothing should be removed as should all jewelry that could act as a tourniquet as swelling occurs, but burned clothing stuck to the skin must not be removed. Cooling the burn with cold running water has been shown to be beneficial if accomplished within 30 minutes of the injury.[18] The pain or inflammation can then be effectively treated using acetaminophen (paracetamol), or ibuprofen. Ice, butter, cream and ointment cannot be used since they can worsen the burn.[19]

Severe burn patients are often treated through trauma resuscitation, airway management, fluid resuscitation, blood transfusion, wound management, and skin grafting, as well as the use of antibiotics.[3][20]

Outcome

For people who are hospitalized for thermal burns, 95% of them survive. Survival rates increased steadily over the last half century due to advances in treating burns as well as more trustful burn centers. According to statistics from 1990 to 1994, the risks of death caused by burns are greater for people older than 60 years of age, burns covering over 40% of the body, and patients suffering inhalation injury. According to the formula developed by authors, patients who have zero risk criteria would have 99.7% chance of survival, ones who have one criterion would have 97% chance of survival, patients having two would have 67% chance, and patients nursing all three would have 10% chance of survival.[3]

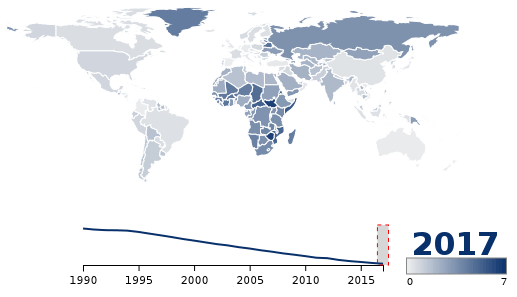

Epidemiology

In the United States, over two million people required medical attention for thermal burns every year. About 1 in 30 of those victims (75,000) are hospitalized for thermal burns every year, with a third of those patients staying in the hospital for more than two months. About 14,000 Americans die each year from burns.[21]

Children

Thermal burns are one of the most common mode of early childhood injury.[11] In the United States, burns are the third most common cause of accidental death among children.[22] Nearly 96,000 children around the world died as a result of thermal burns in 2004,[6] and 61,400 died in 2008 from thermal injuries.[9] Deaths from burns dropped by 55% from 1999 to 2011.[23] Burns are the only mode of unintentional injury which more girls suffer from than boys worldwide, including by fire.[6]

References

- "Fire death rates". Our World in Data. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Phillip L Rice, Jr.; Dennis P Orgill. "Classification of burns". UpToDate. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Phillip L Rice, Jr.; Dennis P Orgill. "Emergency care of moderate and severe thermal burns in adults". UpToDate. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Eisen, Sarah; Murphy, Catherine (2009). Murphy, Catherine; Gardiner, Mark; Sarah Eisen (eds.). Training in paediatrics : the essential curriculum. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-19-922773-0.CS1 maint: uses editors parameter (link)

- Maguire, S; Moynihan, S; Mann, M; Potokar, T; Kemp, AM (December 2008). "A systematic review of the features that indicate intentional scalds in children". Burns : Journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 34 (8): 1072–81. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2008.02.011. PMID 18538478.

- Peden, Margie (2008). World report on child injury prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. p. 86. ISBN 978-92-4-156357-4.

- National Burn Repository Pg. i

- Herndon D, ed. (2012). "Chapter 4: Prevention of Burn Injuries". Total burn care (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Saunders. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4377-2786-9. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- "Fire, Burns and Scalds Prevention". Safe Kids Worldwide. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Panté, Michael D. (2009). Advanced Assessment and Treatment of Trauma. pp. 192–194. ISBN 978-0-7637-8114-9. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Burns". KidsHealth. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- "Contact Burn Treatment". Burn Remedies. Archived from the original on 2014-09-22. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Hettiaratchy, Shehan; Dziewulski, Peter (2004-06-12). "Pathophysiology and types of burns". BMJ : British Medical Journal. 328 (7453): 1427–1429. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7453.1427. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 421790. PMID 15191982.

- "Pathophysiology of thermal burn injury" (DOC). Civic Plus. 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Fire Safety Tips". Safe Kids Worldwide. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Eric D. Morgan; William F. Miser. "Skin burns". UpToDate. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Burns and Scalds Prevention Tips". Safe Kids Worldwide. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- http://www.ebmedicine.net/topics.php?paction=showTopicSeg&topic_id=186&seg_id=3853

- "Burns". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Burn Triage and Treatment: Thermal Injuries". Radiation Emergency Medical Management. U.S. Department of Human and Health Resources. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Acute Thermal Burn Injury". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Phillip L Rice, Jr.; Dennis P Orgill. "Emergency care of moderate and severe thermal burns in adults". UpToDate. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- "Burns and Fire Safety Fact Sheet" (PDF). Safe Kids Worldwide. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

External links

- Burns at MedlinePlus