Tropical theileriosis

Tropical theileriosis or Mediterranean theileriosis is a theileriosis of cattle from the Mediterranean and Middle East area, from Morocco to Western parts of India and China. It is a tick-borne disease, caused by Theileria annulata. The vector ticks are of the genus Hyalomma.

The most prominent symptoms are fever and lymph node enlargement. But there is a wide range of clinical manifestations, especially in enzootic areas. Among them, the Doukkala area of Morocco, where the epidemiology and symptomatology of the disease were minutely studied. [1]

The disease was once considered as "benign" in the literature, in comparison to East Coast fever. With the introduction of European breeds into the region, however, it could become of major economic incidence. [2] An efficient treatment with parvaquone, then buparvaquone became available in many countries from the mid-1990s. Animals native to endemic areas appear more tolerant to the disease, buffalos especially, appear less susceptible.[3]

Clinical signs

Body temperature is regularly higher than in any other cattle disease. Fever from 41 to 42°C is common in acute stages. Later on (day 5 to day 10 from the clinical onset), temperature will lower to a normal range (38.0–39.5°C), but the disease will continue to progress, despite a possible apparent clinical improvement (appetite comes back). Afterwards, from D10 to D15, there is a downfall stage, with hypothermia (37 to 38°C), anemia, jaundice, and heart failure. Such animals rarely recover, even with intensive treatment.

Lymph nodes are commonly enlarged and there may be episodes of blood from the nose, difficulty breathing and weight loss.[3]

Other signs, but not present in all cases are :

- Blood-tinged diarrhea, or with obvious blood clots.

- Bruxism(grinding of teeth) can be seen

- Circular raised patches of hair all over the body

- Haemorrhages in the ocular and vaginal mucous membranes

- A degree of anaemia

Diagnosis

Lymph node enlargement and even hyperthermia can occur asymptomatically in enzootic area, during the disease season.

Clinical signs, including lymph node enlargement, anaemia, hyperthermia and history of tick infestation can lead to a suspicion of theileriosis

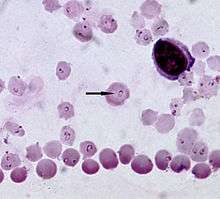

Definitive diagnosis relies on the observation of the pirolplasm stages of the organism in the erythrocytes in blood smears stained with Romanowsky stains. Lymph node aspirates can also be examined for the presence of 'Kock's Blue Bodies' which are schizont stages in lymphocytes. Necropsy reveals 'punched out ulcers' in the abomasum and greyish raised 'infarcts' on kidneys. Numerous serological tests like ELISA, and indirect immunofluorescence test and PCR can also help diagnosis.[3]

Treatment and control

Buparvaquone, halofuginone and tetracycline and butalex and oxytetracycline have all shown to be effective. Tick control should be considered, but resistance to parasiticide products may be increasing.[3] There are various options for controlling ticks of domestic animals, including: topical application of parasiticidal chemicals in dip baths or spray races or pour-on formulations, spraying parasiticides on walls of cattle pens, and rendering the walls of cattle pens smooth with mortar to stop ticks molting there. Selection of cattle for good ability to acquire immune resistance to ticks is potentially effective.

Endemic stability is a state where animals are affected at a low levels or not as susceptible to the disease, and this may be encouraged in endemic areas.[3]

Vaccination is available and should be performed in breeds that are susceptible to infection.[3]

Live attenuated vaccine are being used in many countries like India, Iran, Turkey etc. Which is a basically a Lymphocyte infected with Theileria annulata schizont stage and passaged for attenuation.

References

- N. EL HAJ, M. KACHANI, M. BOUSLIKHANE, H. OUHELLI, A.T. AHAMI, J. KATENDE et S.P. MORZARIA. Séro-épidémiologie de la theilériose à Theileria annulata et de la babésiose à Babesia bigemina au Maroc.

- With mortalities up to 50 to 80 percent in the 1980s (L. Mahin).

- Theileriosis - Cattle reviewed and published by WikiVet, accessed 11 October 2011.

- Chakraborty, S.; Roy, S.; Mistry, H.U.; Murthy, S.; George, N.; Bhandari, V.; Sharma, P. (2017). "Potential Sabotage of Host Cell Physiology by Apicomplexan Parasites for Their Survival Benefits". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 1261. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01261. PMC 5645534. PMID 29081773.