Tear of meniscus

A tear of a meniscus is a rupturing of one or more of the fibrocartilage strips in the knee called menisci. When doctors and patients refer to "torn cartilage" in the knee, they actually may be referring to an injury to a meniscus at the top of one of the tibiae. Menisci can be torn during innocuous activities such as walking or squatting. They can also be torn by traumatic force encountered in sports or other forms of physical exertion. The traumatic action is most often a twisting movement at the knee while the leg is bent. In older adults, the meniscus can be damaged following prolonged 'wear and tear'. Especially acute injuries (typically in younger, more active patients) can lead to displaced tears which can cause mechanical symptoms such as clicking, catching, or locking during motion of the joint.[1] The joint will be in pain when in use, but when there is no load, the pain goes away.

| Tear of meniscus | |

|---|---|

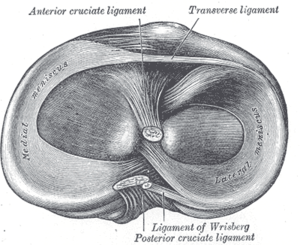

| |

| Head of right tibia seen from above, showing menisci and attachments of ligaments | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

A tear of the medial meniscus[2] can occur as part of the unhappy triad, together with a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament.

Signs and symptoms

The common signs and symptoms of a torn meniscus are knee pain, particularly along the joint line, and swelling. These are worse when the knee bears more weight (for example, when running). Another typical complaint is joint locking, when the affected person is unable to straighten the leg fully. This can be accompanied by a clicking feeling. Sometimes, a meniscal tear also causes a sensation that the knee gives way.

A person with a torn meniscus can sometimes remember a specific activity during which the injury was sustained. A tear of the meniscus commonly follows a trauma which involves rotation of the knee while it was slightly bent. These maneuvers also exacerbate the pain after the injury; for example, getting out of a car is often reported as painful.

Causes

There are two menisci in the knee. They sit between the thigh bone and the shin bone. While the ends of the thigh bone and the shin bone have a thin covering of soft hyaline cartilage, the menisci are made of tough fibrocartilage and conform to the surfaces of the bones they rest on. One meniscus rests on the medial tibial plateau; this is the medial meniscus. The other meniscus rests on the lateral tibial plateau; this is the lateral meniscus.

These menisci act to distribute body weight across the knee joint. Without the menisci, the weight of the body would be unevenly applied to the bones in the legs (the femur and tibia). This uneven weight distribution would cause the development of abnormal excessive forces leading to early damage of the knee joint. The menisci also contribute to the stability of the joint.

The menisci are nourished by small blood vessels but have a large area in the center with no direct blood supply (avascular). This presents a problem when there is an injury to the meniscus, as the avascular areas tend not to heal. Without the essential nutrients supplied by blood vessels, healing cannot take place.

The two most common causes of a meniscal tear are traumatic injury (often seen in athletes) and degenerative processes, which are the most common tear seen in all ages of patients. Meniscal tears can occur in all age groups. Traumatic tears are most common in active people aged 10–45. Traumatic tears are usually radial or vertical in the meniscus and more likely to produce a moveable fragment that can catch in the knee and therefore require surgical treatment.

A meniscus can tear due to an internally or externally rotated knee in a flexed position, with the foot in a flexed position.[3] It is not uncommon for a meniscal tear to occur along with injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament ACL and the medial collateral ligament MCL — these three problems occurring together are known as the "unhappy triad," which is seen in sports such as football when the player is hit on the outside of the knee. Individuals who experience a meniscal tear usually experience pain and swelling as their primary symptoms. Another common complaint is joint locking, or the inability to completely straighten the joint. This is due to a piece of the torn cartilage preventing the normal functioning of the knee joint.

Degenerative tears are most common in people from age 40 upward but can be found at any age, especially with obesity. Degenerative meniscal tears are thought to occur as part of the aging process when the collagen fibers within the meniscus start to break down and lend less support to the structure of the meniscus. Degenerative tears are usually horizontal, producing both an upper and a lower segment of the meniscus. These segments do not usually move out of place and are therefore less likely to produce mechanical symptoms of catching or locking.

Risk factors

The meniscus is made of cartilage, a viscoelastic material, which makes it more susceptible to rate of loading injuries. Repetitive loading can also lead to injury. Recent studies have shown people who experience rapid rate of loading and/or repetitive loading to be the most susceptible to meniscus tears. People over the age of 60 who have working conditions in which squatting and kneeling are common are more susceptible to degenerative meniscal tears.[4] Athletes who constantly experience a high rate of loading (i.e. soccer, rugby) are also susceptible to meniscus tears.[4] Studies have also shown with increasing time between ACL injury and ACL reconstruction, there is an increasing chance of meniscus tears. This study showed meniscus tears occurring at a rate of 50–70% depending on how long after the ACL injury the surgery occurred.[5] Meniscal ramp lesions (tears of the medial meniscus posterior horn at the menisco-capsular junction occur in approximately 25% of ACL-injured knees.[6] Lateral meniscal root tears occur in approximately 7% of ACL injured knees[7]

Pathophysiology

The force distribution is across the knee joint, increasing force concentration on the cartilage and other joint structures.

Damage to the meniscus due to rotational forces directed to a flexed knee (as may occur with twisting sports) is the usual underlying mechanism of injury. A valgus force applied to a flexed knee with the foot planted and the femur rotated externally can result in a lateral meniscus tear. A varus force applied to the flexed knee when the foot is planted and the femur rotated internally result in a tear of the medial meniscus.

Tears produce rough surfaces inside the knee, which cause catching, locking, buckling, pain, or a combination of these symptoms. Abnormal loading patterns and rough surfaces inside the knee, especially when coupled with return to sports, significantly increase the risk of developing arthritis if not already present.

Anatomy

The menisci are C-shaped wedges of fibrocartilage located between the tibial plateau and femoral condyles. The menisci contain 70% type I collagen.[8] The larger semilunar medial meniscus is attached more firmly than the loosely fixed, more circular lateral meniscus. The anterior and posterior horns of both menisci are secured to the tibial plateaus. Anteriorly, the transverse ligament connects the 2 menisci; posteriorly, the meniscofemoral ligament helps stabilize the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus to the femoral condyle. The coronary ligaments connect the peripheral meniscal rim loosely to the tibia. Although the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) passes in close proximity, the lateral meniscus has no attachment to this structure.[8]

The joint capsule attaches to the entire periphery of each meniscus but adheres more firmly to the medial meniscus. An interruption in the attachment of the joint capsule to the lateral meniscus, forming the popliteal hiatus, allows the popliteus tendon to pass through to its femoral attachment site. Contraction by the popliteus during knee flexion pulls the lateral meniscus posteriorly, avoiding entrapment within the joint space. The medial meniscus does not have a direct muscular connection. The medial meniscus may shift a few millimeters, while the less stable lateral meniscus may move at least 1 cm.

In 1978, Shrive et al. reported that the collagen fibers of the menisci are oriented in a circumferential pattern.[8] When a compressive force is applied in the knee joint, a tensile force is transmitted to the menisci. The femur attempts to spread the menisci anteroposteriorly in extension and mediolaterally in flexion. Shrive et al. further studied the effects of a radial cut in the peripheral rim of the menisci during loading. In joints with intact menisci, the force was applied through the menisci and articular cartilage; however, a lesion in the peripheral rim disrupted the normal mechanics of the menisci and allowed it to spread when a load was applied. The load now was distributed directly to the articular cartilage. In light of these findings, it is essential to preserve the peripheral rim during partial meniscectomy to avoid irreversible disruption of the structure's hoop tension capability.[8]

Diagnosis

Physical examination

After noting symptoms, a physician can perform clinical tests to determine if the pain is caused by compression and impingement of a torn meniscus. The knee is examined for swelling. In meniscal tears, pressing on the joint line on the affected side typically produces tenderness. The McMurray test involves pressing on the joint line while stressing the meniscus (using flexion–extension movements and varus or valgus stress). Similar tests are the Steinmann test (with the patient sitting) and the Apley grind test (a grinding maneuver while the person lies prone and the knee is bent 90°) and the Thessaly test (flexing the affected knee to 20 degrees, pivoting on the knee to see if the pain is reproduced). Bending the knee (into hyperflexion if tolerable), and especially squatting, is typically a painful maneuver if the meniscus is torn. The range of motion of the joint is often restricted.

Cooper's sign is present in over 92% of tears. It is a subjective symptom of pain in the affected knee when turning over in bed at night. Osteoarthritic pain is present with weightbearing, but the meniscal tear causes pain with a twisting motion of the knee as the meniscal fragment gets pinched, and the capsular attachment gets stretched causing the complaint of pain.

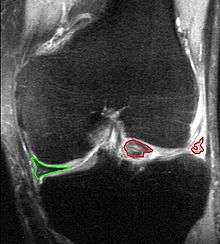

Radiology

X-ray images (normally during weightbearing) can be obtained to rule out other conditions or to see if the patient also has osteoarthritis. The menisci themselves cannot be visualised with plain radiographs. If the diagnosis is not clear from the history and examination, the menisci can be imaged with magnetic resonance imaging (an MRI scan). This technique has replaced previous arthrography, which involved injecting contrast medium into the joint space. In straightforward cases, knee arthroscopy allows quick diagnosis and simultaneous treatment. Recent clinical data shows that MRI and clinical testing are comparable in sensitivity and specificity when looking for a meniscal tear.

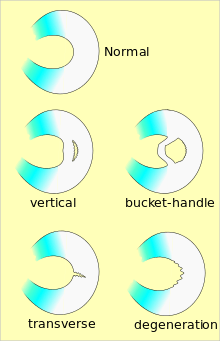

Classification

A meniscal tear can be classified in various ways, such as by anatomic location or by proximity to blood supply. Various tear patterns and configurations have been described.[9] These include:

- Radial tears

- Flap or parrot-beak tears

- Peripheral, longitudinal tears

- Bucket-handle tears

- Horizontal cleavage tears

- Complex, degenerative tears

These tears can then be further classified by their proximity to the meniscus blood supply, namely whether they are located in the “red-red,” “red-white,” or “white-white” zones.

The functional importance of these classifications, however, is to ultimately determine whether a meniscus is repairable. The repairability of a meniscus depends on a number of factors. These include:

- Age/strength

- Activity level

- Tear pattern

- Chronicity of the tear

- Associated injuries (anterior cruciate ligament injury)

- Healing potential

Prevention

Tear of a meniscus is a common injury in many sports. The menisci hold 30–50% of the body load in standing position.[10] Some sports where a meniscus tear is common are American football, association football, ice hockey and tennis. Regardless of what the activity is, it is important to take the correct precautions to prevent a meniscus tear from happening.

Clothing

There are three major ways of preventing a meniscus tear. The first of these is wearing the correct footwear for the sport and surface that the activity is taking place on. This means that if the sport being played is association football, cleats are an important item in reducing the risk of a meniscus tear.[11] The proper footwear is imperative when engaging in physical activity because one off-balanced step could mean a meniscus tear.[12] It is highly advised that cleats contain a sole that molds around the foot, no fewer than fourteen cleats per shoe, no lower than a half inch diameter of the cleat tip, and at most, a three-eighths inch of cleat length.[13]

Stretches

The second way to prevent a meniscus tear is to strengthen and stretch the major leg muscles.[14] Those muscles include the hamstrings, quadriceps, and calf muscles. One popular exercise used to strengthen the hamstrings is the leg curl. It is also important to properly stretch the hamstrings; doing standing toe touches can do this. Seated leg extensions strengthen the quadriceps and doing the quadriceps stretch will help loosen the muscles. Toe raises are used to strengthen and stretch the calves.[14] Adequate muscle mass and strength may also aid in maintaining healthy knees. The use of the parallel squat increases much needed stability in the knee if executed properly. Execution of the parallel squat will develop the lower body muscles that will strengthen the hips, knees, and ankles.[15]

Technique

The last major way to prevent a tear in the meniscus is learning proper technique for the movement that is taking place.[16] For the sports involving quick powerful movements it is important to learn how to cut, turn, land from a jump, and stop correctly. It is important to take the time out to perfect these techniques when used. These three major techniques will significantly prevent and reduce the risk of a meniscus tear.

Treatment

Presently, treatments make it possible for quicker recovery. If the tear is not serious, physical therapy, compression, elevation and icing the knee can heal the meniscus.[17] More serious tears may require surgical procedures. Surgery, however, does not appear to be better than non-surgical care.[18]

Conservative treatments

Initial treatment may include physical therapy, bracing, anti-inflammatory drugs, or corticosteroid injections to increase flexibility, endurance, and strength.[19]

Exercises can strengthen the muscles around the knee, especially the quadriceps. Stronger and bigger muscles will protect the meniscus cartilage by absorbing a part of the weight. The patient may be given paracetamol or anti-inflammatory medications.

For patients with non-surgical treatment, physical therapy program is designed to reduce symptoms of pain and swelling at the affected joint. This type of rehabilitation focuses on maintenance of full range of motion and functional progression without aggravating the symptoms.[20] Physical therapists can use modalities such as electric stimulation, cold therapy, and ultrasonography.

Recently, accelerated rehabilitation programs have been used and shown to be as successful as the conservative program.[21] The program reduces the time the patient spends using crutches and allows weight bearing activities. The less conservative approach allows the patient to apply a small amount of stress and prevent range of motion losses.[21] It is likely that a patient with a peripheral tear may pursue the accelerated program and a patient with a larger tear will use the conservative program.

Surgery

Arthroscopy is a surgical technique in which a joint is operated on using an endoscopic camera as opposed to open surgery on the joint. The meniscus can either be repaired or completely removed; this is described in further detail below.[17] It should not be recommended for a degenerative meniscus tear, unless there is locking or catching of the knee, recurrent effusion or persistent pain.[19] Evidence suggests that it is no better than conservative management in those with and without osteoarthritis.[22][23] There does not appear to be any benefit in adults with a tear of the meniscus who have mild arthritis.[23]

An independent international guideline panel that did not have any conflicts of interest makes a strong recommendation against arthroscopy for degenerative meniscus tears; this conclusion was reached on the basis that there is high-quality evidence that there is no lasting benefit and less than 15% of people even have a small short-term benefit.[22] The disadvantages of arthroscopy for meniscal tear repair include a two to six week recovery time and rare but serious adverse effects that can occur, including blood clots in the legs, surgical site infections, and nerve damage.[24][25][26] The BMJ Rapid Recommendation includes infographics and shared decision-making tools to facilitate a conversation between doctors and patients about the risks and benefits of arthroscopic surgery.[22]

If the injury to the meniscus is isolated, then the knee would be relatively stable. However, if another injury such as an anterior cruciate ligament injury (torn ACL) was coupled with a torn meniscus, then an arthroscopy would be performed. A meniscal repair has a higher success rate if there is an adequate blood supply to the peripheral rim.[27] The interior of the meniscus is avascular, but the blood supply can penetrate up to about 6 millimeters or a quarter inch. Therefore, meniscus tears that occur near the peripheral rim are able to heal after a meniscal repair. A study conducted by Heckman, Barber-Westin & Noyes found that it is better to repair the meniscus than rather remove it (meniscectomy). The amount of rehabilitation time required for a repair is longer than a meniscectomy, but removing the meniscus can cause osteoarthritis problems. If the meniscus is removed, the patient will be in rehab for about four to six weeks. If a repair is conducted, then the patient will need four to six months. If physical therapy does not resolve the symptoms, or in cases of a locked knee, then surgical intervention may be required. Depending on the location of the tear, a repair may be possible. In the outer third of the meniscus, an adequate blood supply exists and a repair will likely heal.[1] Usually younger patients are more resilient and respond well to this treatment, while older, more sedentary patients do not have a favorable outcome after a repair.[28]

Meniscus transplants

Meniscus transplants are accomplished successfully regularly, although it is still somewhat of a rare procedure and many questions surrounding its use remain.[28][29] Side effects of meniscectomy include:

- The knee loses its ability to transmit and distribute load and absorb mechanical shock.

- Persistent and significant swelling and stiffness in the knee.

- The knee may be not be fully mobile; there may be the sensation of knee locking or buckling in the knee.

- The full knee may be in full motion after tear of meniscus.

- Increases progression of arthritis and time to knee replacement.

Meniscus implants

Another treatment approach in development is a meniscus implant or "artificial meniscus." While many artificial joints and bionic body parts are available to patients, including arms, legs, joints and other body parts, a prosthetic replacement for the meniscus has eluded modern medicine.[30] Several initiatives are underway.

The first to be implanted in humans is called the NUsurface Meniscus Implant. The surgery took place in January 2015 at The Ohio State University's Wexner Medical Center.[31][32] The NUsurface Implant is made from medical grade plastic and is designed not to require fixation to bone or soft tissue.[33] Two FDA-approved clinical trials evaluating the implant completed enrollment in June 2018.[34] The manufacturer recently received breakthrough designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and is expecting to file for regulatory approval in the U.S. in the next year.[35][36] If approved by the FDA, the implant could be a good option for younger, active patients who are considered too young for knee replacement because that surgery only lasts about 10 years.[37]

Other early stage meniscus implants include TRAMMPOLIN and Orthonika.[38][39][40]

Scientists are also working to grow an artificial meniscus in the lab. Scientists from Cornell and Columbia universities grew a new meniscus inside the knee joint of a sheep using a 3-D printer and the body's own stem cells.[30][41] Similarly, researchers at Scripps Clinic’s Shiley Center for Orthopaedic Research and Education have also reported growing a whole meniscus. Animal testing will be needed before the replacement meniscus can be used in people, and then clinical trials would follow to determine its effectiveness. Currently, there's no timeline for the clinical trials, but it is estimated it will take years to determine if the lab-grown meniscus is safe and effective.[42]

Post-surgical rehabilitation

After a successful surgery for treating the destroyed part of the meniscus, patients must follow a rehabilitation program to have the best result. The rehabilitation following a meniscus surgery depends on whether the entire meniscus was removed or repaired.

If the destroyed part of the meniscus was removed, patients can usually start walking using a crutch a day or two after surgery. Although each case is different, patients return to their normal activities on average after a few weeks (2 or 3). Still, a completely normal walk will resume gradually, and it's not unusual to take 2–3 months for the recovery to reach a level where a patient will walk totally smoothly. Many meniscectomy patients don't ever feel a 100% functional recovery, but even years after the procedure they sometimes feel tugging or tension in a part of their knee. There is little medical follow-up after meniscectomy and official medical documentation tends to ignore the imperfections and side-effects of this procedure.

If the meniscus was repaired, the rehabilitation program that follows is a lot more intensive. After the surgery a hinged knee brace is sometimes placed on the patient. This brace allows controlled movement of the knee. The patient is encouraged to walk using crutches from the first day, and most of the times can put partial weight on the knee.

Improving symptoms, restoring function, and preventing further injuries are the main goals when rehabilitating.[43] By the end of rehabilitation, normal range of motion, function of muscles and coordination of the body are restored.[43] Personalized rehabilitation programs are designed considering the patient’s surgery type, location repaired (medial or lateral), simultaneous knee injuries, type of meniscal tear, age of patient, condition of the knee, loss of strength and ROM, and the expectations and motivations of the patient.[44]

Phase I

There are three phases that follow meniscal surgery. Each phase consists of rehabilitation goals, exercises, and criteria to move on to the next phase. Phase I starts immediately following surgery to 4–6 weeks or until the patient is able meet progression criteria. The goals are to restore normal knee extension, reduce and eliminate swelling, regain leg control, and protect the knee (Fowler, PJ and D. Pompan, 1993). During the first 5 days following the surgery, a passive continuous motion machine is used to prevent a prolonged period of immobilization which leads to muscular atrophy and delays functional recovery.[45] During the 4–6 weeks post-surgical, active and passive non-weight bearing motions which flex the knee up to 90° are recommended. For patients with meniscal transplantation, further knee flexion can damage the allograft because of the increased shear forces and stresses. If any weight-bearing exercises are applied, a controlled brace should be worn on the knee to keep the knee at near (<10°) or full extension.[46] The suggested exercises target increasing the patient’s ROM, muscular and neuromuscular strength, and cardiovascular endurance. Aquatic therapy, or swimming, can be used to rehab patients because it encompasses ROM, strength, and cardiovascular exercises while relieving stress on the body. It has also been shown to significantly improve dependent edema and pain symptoms.[47] No pain gait without crutches, swelling and 4–6 weeks after surgery are the criteria to begin the next phase (Ulrich G.S., and S Aroncyzk, 1993).

Phase II

This phase of the rehabilitation program is 6 to 14 weeks after the surgery. The goals for Phase II include being able to restore full ROM, normalized gait, and performing functional movements with control and no pain (Fowler, PJ and D. Pompan, 1993). Also, muscular strengthening and neuromuscular training are emphasized using progressive weight bearing and balance exercises. Exercises in this phase can increase knee flexion for more than 90°.[48] Advised exercises include stationary bicycle, standing on foam surface with two and one leg, abdominal and back strengthening, and quadriceps strengthening. The proposed criteria include normal gait on all surfaces and single leg balance longer than 15 seconds (Ulrich G.S., and S Aroncyzk, 1993).

Phase III

Patients begin exercises in phase III 14 to 22 weeks after surgery. Phase III’s goal and final criteria is to perform sport/work specific movements with no pain or swelling (Fowler, PJ and D. Pompan, 1993). Drills for maximal muscle control, strength, flexibility,[48] movements specific to patient’s work/sport, low to high rate exercises, and abdominal and back strengthening exercises are all recommended exercises (Ulrich G.S., and S Aroncyzk, 1993). Exercises to increase cardiovascular fitness are also applied to fully prepare the patients to return to their desired activities.

If the progression criteria are met, the patient can gradually return to "high-impact" activities (like running). However, "heavier activities", like running, skiing, basketball etc., generally any activities where knees bear sudden changes of the direction of movement can lead to repeated injuries. When planning sport activities it makes sense to consult a physical therapist and check how much impact the sport will have on the knee.

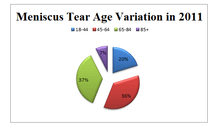

Epidemiology

The meniscal tear is the most common knee injury. It tends to be more frequent in sports that have rough contact or pivoting sports such as soccer. It is more common in males than females, with a ratio of about two and a half males to one female. Males between the ages of 31 and 40 tend to tear their meniscus more frequently than younger men. Females seem to be more likely to tear their meniscus between the ages of 11 and 20.

People who work in straining jobs such as construction or professional sports are also more likely to have a meniscal tear because of the different tensions to which their knees are subjected.

According to the United States National Library of Medicine, the isolated medial meniscal tear occurs more frequently than any other tear associated with the meniscus. The prevalence of meniscus tears is the same for both knees. In a few different studies the BMI of a person is shown to have a greater effect on the frequency of a meniscus tear; having a higher BMI will result in more weight on the joints, which can cause the knee to be non-aligned, which causes more weight on the muscles, resulting in an easier tear.

In 2008 the U.S Department of Health and Human Services reported a combined total of 2,295 discharges for the principal diagnosis of tear of lateral cartilage/meniscus (836.0), tear of medial cartilage/meniscus (836.1), and tear of cartilage/meniscus (836.2). Females had a total of 53.49% discharges, while males had 45.72%. Individuals between the ages of 45 and 68 had an average of 31.73% discharges followed by age group 65–84, with 28.82%. The average length of stay for a patient diagnosed with torn menisci was 2.7 days for males and 3.7 days for females. There was a report of 6,941 hospital discharges for knee repair. Individuals between age 18 and 44 were among the highest with 37.37% total of discharges, followed by the age group 45–64, with a percentage of 36.34%. Males had a slightly higher number of discharges (50.78%) than females (48.66%). The average length of stay for both male and female patients in a hospital setting was 3.1.[49]

References

- Meniscus Injuries at eMedicine

- Shelbourne KD, Nitz PA (1991). "The O'Donoghue triad revisited. Combined knee injuries involving anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligament tears". Am J Sports Med. 19 (5): 474–7. doi:10.1177/036354659101900509. PMID 1962712.

- Poulsen MR, Johnson DL (February 2011). "Meniscal injuries in the young, athletically active patient". Phys Sportsmed. 39 (1): 123–30. doi:10.3810/psm.2011.02.1870. PMID 21378495.

- Snoeker, BA.; Bakker, EW.; Kegel, CA.; Lucas, C. (Jun 2013). "Risk factors for meniscal tears: a systematic review including meta-analysis". J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 43 (6): 352–67. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.4295. PMID 23628788.

- Papastergiou, SG.; Koukoulias, NE.; Mikalef, P.; Ziogas, E.; Voulgaropoulos, H. (Dec 2007). "Meniscal tears in the ACL-deficient knee: correlation between meniscal tears and the timing of ACL reconstruction". Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 15 (12): 1438–44. doi:10.1007/s00167-007-0414-9. PMID 17899001.

- Sonnery-Cottet, Bertrand; Praz, Cesar; Rosenstiel, Nikolaus; Blakeney, William G.; Ouanezar, Herve; Kandhari, Vikram; Vieira, Thais Dutra; Saithna, Adnan (November 2018). "Epidemiological Evaluation of Meniscal Ramp Lesions in 3214 Anterior Cruciate Ligament–Injured Knees From the SANTI Study Group Database: A Risk Factor Analysis and Study of Secondary Meniscectomy Rates Following 769 Ramp Repairs" (PDF). The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 46 (13): 3189–3197. doi:10.1177/0363546518800717. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 30307740.

- Praz, Cesar; Vieira, Thais Dutra; Saithna, Adnan; Rosentiel, Nikolaus; Kandhari, Vikram; Nogueira, Helder; Sonnery-Cottet, Bertrand (March 2019). "Risk Factors for Lateral Meniscus Posterior Root Tears in the Anterior Cruciate Ligament–Injured Knee: An Epidemiological Analysis of 3956 Patients From the SANTI Study Group". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 47 (3): 598–605. doi:10.1177/0363546518818820. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 30649904.

- "Anatomy of Meniscus" 1994. May. 21011. Anatomy, Meniscal Tear.

- Classification of meniscal tear, sportsmd.

- Rath, E.; Richmond, JC. (Aug 2000). "The menisci: basic science and advances in treatment". Br J Sports Med. 34 (4): 252–7. doi:10.1136/bjsm.34.4.252. PMC 1724227. PMID 10953895.

- Papalia, R.; Del Buono, A.; Osti, L.; Denaro, V.; Maffulli, N. (2011). "Meniscectomy as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review". Br Med Bull. 99 (1): 89–106. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldq043. PMID 21247936.

- Peña, E.; Calvo, B.; Martínez, MA.; Palanca, D.; Doblaré, M. (Jun 2005). "Finite element analysis of the effect of meniscal tears and meniscectomies on human knee biomechanics". Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 20 (5): 498–507. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.01.009. PMID 15836937.

- Torg J, Quesdenfeld T (1971). "Effect of shoe type and cleat length on incidence and severity of knee injuries among high school football players". Research Quarterly. 42 (2): 203–211. doi:10.1080/10671188.1971.10615058.

- Fithian, DC.; Kelly, MA.; Mow, VC. (March 1990). "Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci". Clin Orthop Relat Res (252): 19–31. doi:10.1097/00003086-199003000-00004. PMID 2406069.

- Escamilla RF (2001). "Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise". Med Sci Sports Exerc. 33 (1): 127–41. doi:10.1097/00005768-200101000-00020. PMID 11194098.

- Rodkey, WG. (2000). "Basic biology of the meniscus and response to injury". Instr Course Lect. 49: 189–93. PMID 10829174.

- Shelbourne KD, Patel DV, Adsit WS, Porter DA (1996). "Rehabilitation after meniscal repair". Clin Sports Med. 15 (3): 595–612. PMID 8800538.

- Monk, P; Garfjeld Roberts, P; Palmer, AJ; Bayliss, L; Mafi, R; Beard, D; Hopewell, S; Price, A (March 2017). "The Urgent Need for Evidence in Arthroscopic Meniscal Surgery". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 45 (4): 965–973. doi:10.1177/0363546516650180. PMID 27432053.

- American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (24 April 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, retrieved 29 July 2014, which cites

- Herrlin, SV; Wange, PO; Lapidus, G; Hållander, M; Werner, S; Weidenhielm, L (Feb 2013). "Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 21 (2): 358–64. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-1960-3. PMID 22437659.

- Goldblatt JP, LaFrance RM, Smith JS (2009). "Managing meniscal injuries: The treatment". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 26 (12): 471–7.

- Barber FA, Click SD (1997). "Meniscus repair rehabilitation with concurrent anterior cruciate reconstruction". Arthroscopy. 13 (4): 433–7. doi:10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90120-1. PMID 9276048.

- Siemieniuk RA, Harris IA, Agoritsas T, Poolman RW, Brignardello-Petersen R, Van de Velde S, Buchbinder R, Englund M, Lytvyn L, Quinlan C, Helsingen L, Knutsen G, Olsen NR, Macdonald H, Hailey L, Wilson HM, Lydiatt A, Kristiansen A, et al. (May 2017). "Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline". BMJ. 357: j1982. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1982. PMC 5426368. PMID 28490431.

- Khan, M.; Evaniew, N.; Bedi, A.; Ayeni, O. R.; Bhandari, M. (25 August 2014). "Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 186 (14): 1057–64. doi:10.1503/cmaj.140433. PMC 4188648. PMID 25157057.

- Friberger Pajalic, Katarina; Turkiewicz, Aleksandra; Englund, Martin (1 June 2018). "Update on the risks of complications after knee arthroscopy". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 19 (1): 179. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-2102-y. PMC 5984803. PMID 29859074.

- Abram, SGF; Judge, A; Beard, DJ; Price, AJ (24 September 2018). "Adverse outcomes after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a study of 700 000 procedures in the national Hospital Episode Statistics database for England". Lancet. 392 (10160): 2194–2202. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31771-9. PMC 6238020. PMID 30262336.

- Hame, Sharon L.; Nguyen, Virginia; Ellerman, Jessica; Ngo, Stephanie S.; Wang, Jeffrey C.; Gamradt, Seth C. (2012-04-10). "Complications of Arthroscopic Meniscectomy in the Older Population". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 40 (6): 1402–1405. doi:10.1177/0363546512443043. PMID 22495145.

- Scott GA, Jolly BL, Henning CE (1986). "Combined posterior incision and arthroscopic intra-articular repair of the meniscus. An examination of factors affecting healing". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 68 (6): 847–61. doi:10.2106/00004623-198668060-00006. PMID 3755440.

- Sohn DH, Toth AP (April 2008). "Meniscus transplantation: current concepts". J Knee Surg. 21 (2): 163–72. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1247813. PMID 18500070.

- Matava MJ (February 2007). "Meniscal allograft transplantation: a systematic review". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 455: 142–57. doi:10.1097/BLO.0b013e318030c24e. PMID 17279042.

- Beck, Melinda (2015-05-04). "New Fixes for Worn Knees". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- "Ohio State surgeon performs country's 1st meniscus implant surgery". The Lantern. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- "Artificial Cartilage Could Protect Runners From Arthritis, Knee Replacements". US News & World Report. February 27, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "Active Implants launches another NUsurface meniscal implant trial site – MassDevice". www.massdevice.com. 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- "Active Implants Wraps up NUsurface Trial Enrollment | Orthopedics This Week". ryortho.com. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- "NUsurface® | Meniscus Implant | Knee Pain | Active Implants". Active Implants. 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- "Active Implants Receives FDA Breakthrough Device Designation for NUsurface® Meniscus Implant". www.businesswire.com. 2019-09-19. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- "New hope for treating knee injuries". Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- Orthopaedic Research Laboratory (ORL) Nijmegen. "Biostable Prosthesis of a Meniscus". orthopaedicresearchlab.nl. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- BarrySmit. "TRAMMPOLIN - Meniscus compleet vervangen". www.nmtrix.com. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- "Total Meniscus Replacement for the Knee | Orthonika". Orthonika. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- "New Fixes for Worn Knees". Hospital for Special Surgery. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- Fikes, Bradley J. "Lab-grown meniscus could one day prevent arthritis in knees". sandiegouniontribune.com. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- Jeong, HJ.; Lee, SH.; Ko, CS. (Sep 2012). "Meniscectomy". Knee Surg Relat Res. 24 (3): 129–36. doi:10.5792/ksrr.2012.24.3.129. PMC 3438273. PMID 22977789.

- Brindle, T.; Nyland, J.; Johnson, DL. (Apr 2001). "The meniscus: review of basic principles with application to surgery and rehabilitation". J Athl Train. 36 (2): 160–9. PMC 155528. PMID 16558666.

- Heckmann TP, Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR (2006). "Meniscal repair and transplantation: indications, techniques, rehabilitation, and clinical outcome". J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 36 (10): 795–814. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.557.8818. doi:10.2519/jospt.2006.2177. PMID 17063840.

- Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, Harner CD (1996). "Rehabilitation following allograft meniscal transplantation: a review of the literature and case study". J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 24 (2): 98–106. doi:10.2519/jospt.1996.24.2.98. PMID 8832473.

- Becker, BE. (Sep 2009). "Aquatic therapy: scientific foundations and clinical rehabilitation applications". PM&R. 1 (9): 859–72. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.05.017. PMID 19769921.

- Cavanaugh JT, Killian SE (2012). "Rehabilitation following meniscal repair". Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 5 (1): 46–58. doi:10.1007/s12178-011-9110-y. PMC 3535118. PMID 22442106.

- "Epidemiology of meniscus". 2006. Web. May. 2011

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tears of meniscus. |