Taurolidine

Taurolidine is an antimicrobial that is used to try to prevent infections in catheters.[1] Side effects and the induction of bacterial resistance is uncommon.[1] It is also being studied as a treatment for cancer.[2]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.039.090 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H16N4O4S2 |

| Molar mass | 284.35 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

It is derived from the endogenous amino acid taurine. Taurolidine’s putative mechanism of action is based on a chemical reaction. During the metabolism of taurolidine to taurinamide and ultimately taurine and water, methylol groups are liberated that chemically react with the mureins in the bacterial cell wall and with the amino and hydroxyl groups of endotoxins and exotoxins. This results in denaturing of the complex polysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide components of the bacterial cell wall and of the endotoxin and in the inactivation of susceptible exotoxins.[3]

Medical uses

Taurolidine is an antimicrobial agent used in an effort to prevent catheter infections. It however is not approved for this use in the United States as of 2011.[4]

- Catheter lock solution in home parenteral nutrition (HPN) or total parenteral nutrition (TPN): catheter-related blood stream infections (CRBSI) remains the most common serious complication associated with long-term parenteral nutrition. The use of taurolidine as a catheter lock solution shows a reduction of CRBSI.[1][5] The overall quality of the evidence however is not strong enough to justify routine use.[1][5]

- Catheter lock solution: Taurolidine decreases the adherence of bacteria and fungi to host cells by destructing the fimbriae and flagella and thus prevent the biofilm formation.[6][7] Taurolidine is the active ingredient of antimicrobial catheter lock solutions for the prevention and treatment of catheter related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) and is suitable for use in all catheter based vascular access devices.[8][9] Bacterial resistance against taurolidine has never been observed in various studies.[10][11]

- The use of a taurolidine lock solution may decrease the risk of catheter infection in children with cancer but the evidence is tentative.[12]

Side effects

No systemic side effects have been identified. The safety of taurolidine has also been confirmed in clinical studies with long-term intravenous administration of high doses (up to 20 grams daily). In the body, taurolidine is metabolized rapidly via the metabolites taurultam and methylol taurinamide, which also have a bactericidal action, to taurine, an endogenous aminosulphonic acid, carbon dioxide and water. Therefore, no toxic effects are known or expected in the event of accidental injection. Burning sensation while instilling, numbness, erythema, facial flushing, headache, epistaxis, and nausea have been reported.[13]

Toxicology

Taurolidine has a relatively low acute and subacute toxicity.[1] Intravenous injection of 5 grams taurolidine into humans over 0.5–2 hours produce only burning sensation while instilling, numbness, and erythema at the injection sites.[13] For treatment of peritonitis, taurolidine was administered by peritoneal lavage, intraperitoneal instillation or intravenous infusion, or by a combination thereof. The total daily dose ranged widely from 0.5 to 50 g. The total cumulative dose ranged from 0.5 to 721 g. In those patients who received intravenous taurolidine, the daily intravenous dose was usually 15 to 30 g but several patients received up to 40 g/day. Total daily doses of up to 40 g and total cumulative doses exceeding 300 g were safe and well tolerated.[13][14][15][16][17]

Pharmacology

- Metabolism: Taurolidine and taurultam are quickly metabolized to taurinamide, taurine, carbon dioxide and water. Taurolidine exists in equilibrium with taurultam and N-methylol-taurultam in aqueous solution.[18]

- Pharmacokinetic (elimination): The half-life of the terminal elimination phase of taurultam is about 1.5 hours, and of the taurinamide metabolite about 6 hours. 25% of the taurolidine dose applied is renally eliminated as taurinamide and/or taurine.[14][15][19]

Mechanism of action

Following administration of taurolidine, the antimicrobial and antiendotoxin activity of the taurolidine molecule is conferred by the release of three active methylol (hydroxymethyl) groups as taurolidine is rapidly metabolized by hydrolysis via methylol taurultam to methylol taurinamide and taurine. These labile N-methylol derivatives of taurultam and taurinamide react with the bacterial cell-wall resulting in lysis of the bacteria, and by inter- and intramolecular cross-linking of the lipopolysaccharide-protein complex, neutralization of the bacterial endotoxins which is enhanced by enzymatic activation. This mechanism of action is accelerated and maximised when taurolidine is pre-warmed to 37 °C (99 °F). Microbes are killed and the resulting toxins are inactivated; the destruction time in vitro is 30 minutes.[20]

The chemical mode of action of taurolidine via its reactive methylol groups confers greater potency in vivo than indicated by in vitro minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, and also appears to preclude susceptibility to resistance mechanisms.[15]

Taurolidine binding to lipopolysaccharides (LPS) prevents microbial adherence to host epithelial cells, thereby prevents microbial invasion of uninfected host cells. Although the mechanism underlying its antineoplastic activity has not been fully elucidated, it may be related to this agent's anti-adherence property.[6][7] Taurolidine has been shown to block interleukin 1 (IL-1) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).[21] In addition, taurolidine also promotes apoptosis by inducing various apoptotic factors and suppresses the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein that plays an important role in angiogenesis.[22]

Taurolidine is highly active against the common infecting pathogens associated with peritonitis and catheter sepsis, this activity extends across a wide-spectrum of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and fungi (with no diminution of effect in the presence of biological fluids, e.g. blood, serum, pus).[16][17][23]

- Gram-positive bacteria (MIC of 1–2 mg/mL): Staphylococcus (including multiple-antibiotic resistant coagulase negative strains, methicillin-resistant S. aureus), Streptococcus, Enterococcus.

- Gram-negative bacteria (MIC of 0.5–5 mg/mL): Aerobacter species, Citrobacter species, Enterobacter species, Escherichia coli, Proteus species (indole negative), Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas species (including P. aeruginosa), Salmonella species, Serratia marcescans, Klebsiella species.

- Anaerobes (MIC 0.03–0.3 mg/mL): Bacteroides species (including B. fragilis), Fusobacteria, Clostridium species, Peptostreptococcus anaerobius.

- Fungi (MIC 0.3–5 mg/mL): Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus species, Trichophyton rubrum, Epidermophyton floccosum, Pityrosporum ovale.[11][18][23]

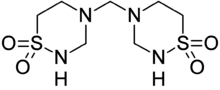

Chemical properties

The chemical name for taurolidine is 4,4'-Methylene-bis(1,2,4-thiadiazinane)-1,1,1’,1'-tetraoxide.

It is a white to off white odourless crystalline powder. It is practically insoluble in chloroform, slightly soluble in boiling acetone, ethanol, methanol, and ethyl acetate, sparingly soluble in water 8 at 20° and ethyl alcohol, soluble in dilute hydrochloric acid, and dilute sodium hydroxide, and freely soluble in N,N-dimethylformamide (at 60 °C).

History

Taurolidine was first synthesized in the laboratories of Geistlich Pharma AG, Switzerland in 1972. Clinical trials begun in 1975 in patients with severe peritonitis.

Research

Taurolidine demonstrates some anti-tumor properties, with positive results seen in early-stage clinical investigations using the drug to treat gastrointestinal malignancies and tumors of the central nervous system.[24] More recently, it has been found to exert antineoplastic activity. Taurolidine induces cancer cell death through a variety of mechanisms. Even now, all the antineoplastic pathways it employs are not completely elucidated. It has been shown to enhance apoptosis, inhibit angiogenesis, reduce tumor adherence, downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokine release, and stimulate anticancer immune regulation following surgical trauma. Apoptosis is activated through both a mitochondrial cytochrome-c-dependent mechanism and an extrinsic direct pathway. A lot of in vitro and animal data support taurolidine's tumoricidal action.[25][26][27] Taurolidine has been used as an antimicrobial agent in the clinical setting since the 1970s and thus far appears nontoxic. The nontoxic nature of taurolidine makes it a favorable option compared with current chemotherapeutic regimens. Few published clinical studies exist evaluating the role of taurolidine as a chemotherapeutic agent. The literature lacks a gold-standard level 1 randomized clinical trial to evaluate taurolidine's potential antineoplastic benefits. However, these trials are currently underway. Such randomized control studies are vital to clarify the role of taurolidine in modern cancer treatment.[22][28]

References

- Liu, Y; Zhang, AQ; Cao, L; Xia, HT; Ma, JJ (2013). "Taurolidine lock solutions for the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79417. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879417L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079417. PMC 3836857. PMID 24278133.

- Neary, PM; Hallihan, P; Wang, JH; Pfirrmann, RW; Bouchier-Hayes, DJ; Redmond, HP (April 2010). "The evolving role of taurolidine in cancer therapy". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 17 (4): 1135–43. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0867-9. PMID 20039217.

- Waser, P.G.; Sibler, E. (1986). "Taurolidine: A new concept in antimicrobial chemotherapy". In A.F. Harms (ed.). Innovative Approaches in Drug Research. Elsevier Science Publishers. pp. 155–169.

- O'Grady, NP; Alexander, M; Burns, LA; Dellinger, EP; Garland, J; Heard, SO; Lipsett, PA; Masur, H; Mermel, LA; Pearson, ML; Raad, II; Randolph, AG; Rupp, ME; Saint, S; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, (HICPAC) (May 2011). "Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 52 (9): e162–93. doi:10.1093/cid/cir257. PMC 3106269. PMID 21460264.

- Bradshaw, Joanne H.; Puntis, John W. L. (2008-08-01). "Taurolidine and catheter-related bloodstream infection: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 47 (2): 179–186. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e318162c428. ISSN 1536-4801. PMID 18664870.

- Gorman, S.P.; McCafferty; et al. (1987). "Reduced adherence of micro-organisms to human mucosal epithelial cells following treatment with Taurolin, a novel antimicrobial agent". J Appl Bacteriol. 62 (4): 315–20. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1987.tb04926.x. PMID 3298185.

- Blenkharn, J.I. (1989). "Anti-adherence properties of taurolidine and noxythiolin". J Chemother. 1 (Suppl 4): 233–4.

- Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Deng, J.; Chen, L.; Yuan, L.; Wu, Y. (2014). "Preventing Catheter-Related Bacteremia with Taurolidine-Citrate Catheter Locks: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Blood Purif. 37: 179–187. doi:10.1159/000360271.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, A-Q.; Cao, L.; Xia, H.-T.; Ma, J.-J. (2013). "Taurolidine Lock Solutions for the Prevention of Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79417. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879417L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079417. PMC 3836857. PMID 24278133.

- Olthof, D.; Rentenaar, R.J.; Rijs, A.J.M.M.; Wanten, G.J.A. (2013). "Absence of microbial adaption to taurolidine in patients on home parenteral nutrition who develop catheter related bloodstream infections and use taurolidine lock". Clin Nutr. 32: 538–542. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2012.11.014.

- Torres-Viera, C.; Thauvin-Eliopoulos, C.; Souli, M.; DeGirolami, P.; Farris, M.G.; Wennersten, C.B.; Sofia, R.D.; Eliopoulos, G.M. (2000). "Aktivities of Taurolidine In Vitro and in Experimental Enterococcal Endocarditis". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 44 (6): 1720–1724. doi:10.1128/aac.44.6.1720-1724.2000. PMC 89943. PMID 10817739.

- Simon, A; Bode, U; Beutel, K (July 2006). "Diagnosis and treatment of catheter-related infections in paediatric oncology: an update". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 12 (7): 606–20. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01416.x. PMID 16774556.

- Gong, L.; Greenberg, H.E.; et al. (2007). "The pharmacokinetics of taurolidine metabolites in healthy volunteers". J Clin Pharmacol. 47 (6): 697–703. doi:10.1177/0091270007299929. PMID 17395893.

- Knight, B.I.; Skellern, G.G.; et al. (1981). "Peritoneal absorption of the antibacterial and antiendotoxin taurolin in peritonitis". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 12 (5): 695–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01292.x. PMC 1401955. PMID 7332737.

- Stendel, R.; Scheurer, L.; et al. (2007). "Pharmacokinetics of taurolidine following repeated intravenous infusions measured by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS of the derivatives taurultame and taurinamide in glioblastoma patients". Clin Pharmacokinet. 46 (6): 513–24. doi:10.2165/00003088-200746060-00005. PMID 17518510.

- Browne, M.K.; MacKenzie, M.; et al. (1978). "A controlled trial of taurolin in established bacterial peritonitis". Surg Gynecol Obstet. 146 (5): 721–4. PMID 347606.

- Browne, M.K. (1981). "The treatment of peritonitis by an antiseptic - taurolin". Pharmatherapeutica. 2 (8): 517–22. PMID 7255507.

- Knight, B.I.; Skellern; et al. (1981). "The characterisation and quantitation by high-performance liquid chromatography of the metabolites of taurolin". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 12 (3): 439–40. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01245.x. PMC 1401804. PMID 7295478.

- Browne, M.K.; Leslie, G.B.; et al. (1976). "Taurolin, a new chemotherapeutic agent". J Appl Bacteriol. 41 (3): 363–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1976.tb00647.x. PMID 828157.

- Braumann, C.; Pfirrman, R.W.; et al. (2013). "Taurolidine, an Effective Multimodal Antimicrobial Drug Versus Traditional Antiseptics and Antibiotics". In C. Willy (ed.). Antiseptics in Surgery - Update 2013. Lindqvist Book Publishing. pp. 119–125.

- Bedrosian, I.; Sofia, R.D.; et al. (1991). "Taurolidine, an analogue of the amino acid taurine, suppresses interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor synthesis in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells". Cytokine. 3 (6): 568–75. doi:10.1016/1043-4666(91)90483-t. PMID 1790304.

- Jacobi, CA; Menenakos, C.; Braumann, C. (October 2005). "Taurolidine--a new drug with anti-tumor and anti-angiogenic effects". Anticancer Drugs. 16 (9): 917–21. doi:10.1097/01.cad.0000176502.40810.b0. PMID 16162968.

- Nösner, K.; Focht, J. (1994). "In-vitro Wirksamkeit von Taurolidin und 9 Antibiotika gegen klinische Isolate aus chirurgischem Einsendegut sowie gegen Pilze". Chirurgische Gastroenterologie. 10 (Suppl 2): 10.

- Stendel, Ruediger; Picht, Thomas; Schilling, Andreas; Heidenreich, Jens; Loddenkemper, Christoph; Jänisch, Werner; Brock, Mario (2004-04-01). "Treatment of glioblastoma with intravenous taurolidine. First clinical experience". Anticancer Research. 24 (2C): 1143–1147. ISSN 0250-7005. PMID 15154639.

- Calabresi, P.; Goulette, F. A.; Darnowski, J. W. (2001-09-15). "Taurolidine: cytotoxic and mechanistic evaluation of a novel antineoplastic agent". Cancer Research. 61 (18): 6816–6821. ISSN 0008-5472. PMID 11559556.

- Clarke, N.W.D.; Wang, J.H.; et al. (2005). "Taurolidine inhibits colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases in vivo and in vitro by inducing apoptosis". Ir J Med Sci. 174 (Supplement 3): 1.

- Stendel, Ruediger; Scheurer, Louis; Stoltenburg-Didinger, Gisela; Brock, Mario; Möhler, Hanns (2003-06-01). "Enhancement of Fas-ligand-mediated programmed cell death by taurolidine". Anticancer Research. 23 (3B): 2309–2314. ISSN 0250-7005. PMID 12894508.

- Neary, Peter M.; Hallihan, Patrick; Wang, Jiang H.; Pfirrmann, Rolf W.; Bouchier-Hayes, David J.; Redmond, Henry P. (2010-04-01). "The evolving role of taurolidine in cancer therapy". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 17 (4): 1135–1143. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0867-9. ISSN 1534-4681. PMID 20039217.