Tampon

A tampon is a feminine hygiene product designed to absorb the menstrual flow by insertion into the vagina during menstruation. Once inserted correctly a tampon is held in place by the vagina and expands as it soaks up menstrual blood. The majority of tampons sold are made of rayon, or a blend of rayon and cotton. Tampons are available in several absorbency ratings.

The average woman may use approximately 11,400 tampons in her lifetime (if she uses only tampons rather than other products).[1]

Several countries regulate tampons as medical devices. In the United States, they are considered to be a Class II medical device by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They are sometimes used for hemostasis in surgery.

Design and packaging

Tampon design varies between companies and across product lines in order to offer a variety of applicators, materials and absorbencies.[2] There are two main categories of tampons based on the way of insertion - digital tampons inserted by finger and applicator tampons. Tampon applicators may be made of plastic or cardboard, and are similar in design to a syringe. The applicator consists of two tubes, an "outer", or barrel, and "inner", or plunger. The outer tube has a smooth surface to aid insertion and sometimes comes with a rounded end that is petaled.[3][4]

The two main differences are in the way the tampon expands when in use; applicator tampons generally expand axially (increase in length), while digital tampons will expand radially (increase in diameter).[5] Most tampons have a cord or string for removal. The majority of tampons sold are made of rayon, or a blend of rayon and cotton. Organic cotton tampons are made from only 100% cotton.[6]

Absorbency ratings

Tampons are available in several absorbency ratings, which are consistent across manufacturers in the U.S.:[7]

- Junior/Light absorbency: 6 g and under

- Regular absorbency: 6–9 g

- Super absorbency: 9–12 g

- Super Plus absorbency 12–15 g

- Ultra absorbency 15–18 g

Absorbency ratings outside the US may be different. The majority of non-US manufacturers use absorbency rating and Code of Practice recommended by EDANA (European Disposals and Nonwovens Association).

| Droplets | Grams | Alternative size description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 droplet | < 6 | |

| 2 droplets | 6–9 | Mini |

| 3 droplets | 9–12 | Regular |

| 4 droplets | 12–15 | Super |

| 5 droplets | 15–18 | |

| 6 droplets | 18–21 |

A piece of test equipment referred to as a Syngina (short for synthetic Vagina) is usually used to test absorbency. The machine uses a condom into which the tampon is inserted, and synthetic menstrual fluid is fed into the test chamber.[8]

Health aspects

Toxic shock syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome was named by Dr. James K. Todd in 1978.[9] Dr. Philip M. Tierno Jr., Director of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology at the NYU Langone Medical Center, helped determine that tampons were behind toxic shock syndrome (TSS) cases in the early 1980s. Tierno blames the introduction of higher-absorbency tampons in 1978, as well as the relatively recent decision by manufacturers to recommend that tampons can be worn overnight, for increased incidences of toxic shock syndrome.[10] However, a later meta-analysis found that the absorbency and chemical composition of tampons are not directly correlated to the incidence of toxic shock syndrome, whereas oxygen and carbon dioxide content is associated more strongly.[11][12]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration suggests the following guidelines for decreasing the risk of contracting TSS when using tampons:[13]

- Follow package directions for insertion

- Choose the lowest absorbency needed for one's flow (test of absorbency is approved by FDA)

- Follow guidelines and directions of tampon usage (located on box's label)

- Consider using cotton or cloth tampons rather than rayon

- Change the tampon at least every 6 to 8 hours or more often if needed

- Alternate usage between tampons and pads

- Avoid tampon usage overnight or when sleeping

- Increase awareness of the warning signs of Toxic Shock Syndrome and other tampon-associated health risks (and remove the tampon as soon as a risk factor is noticed)

Cases of tampon-connected TSS are very rare in the United Kingdom[14][15][16] and United States.[17][18] A study by Tierno also determined that all cotton tampons were less likely to produce the conditions in which TSS can grow, this was done using a direct comparison of 20 brands of tampons including conventional cotton/rayon tampons and 100% organic cotton tampons from Natracare. In fact Dr Tierno goes as far to state that "The bottom line is that you can get TSS with synthetic tampons but not with an all-cotton tampon." [19]

Sea sponges are also marketed as menstrual hygiene products. A 1980 study by the University of Iowa found that commercially sold sea sponges contained sand, grit, and bacteria. Hence, sea sponges could also potentially cause toxic shock syndrome.[20]

Other uses

Clinical use

Tampons are currently being used and tested to restore and/or maintain the normal microbiota of the vagina to treat bacterial vaginosis.[21] Some of these are available to the public but come with disclaimers.[22] The efficacy of the use of these probiotic tampons has not been established.

Environment and waste

Ecological impact varies according to disposal method (whether a tampon is flushed down the toilet or placed in a garbage bin - the latter is the recommended option). Factors such as tampon composition will likewise impact sewage treatment plants or waste processing.[23] The average woman may use approximately 11,400 tampons in her lifetime (if she uses only tampons rather than other products).[1] Tampons are made of cotton, rayon, polyester, polyethylene, polypropylene, and fiber finishes. Aside from the cotton, rayon and fiber finishes, these materials are not bio-degradable. Organic cotton tampons are biodegradable, but must be composted to ensure they break down in a reasonable amount of time. Rayon was found to be more biodegradable than cotton.[24]

Environmentally friendly alternatives to using tampons are the menstrual cup, reusable sanitary pads, menstrual sponges, reusable tampons,[25] and reusable absorbent underwear.[26][27][28]

The Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm carried out a life cycle assessment (LCA) comparison of the environmental impact of tampons and sanitary pads. They found that the main environmental impact of the products was in fact caused by the processing of raw materials, particularly LDPE (low density polyethelene) – or the plastics used in the backing of pads and tampon applicators, and cellulose production. As production of these plastics requires a lot of energy and creates long-lasting waste, the main impact from the life cycle of these products is fossil fuel use, though the waste produced is significant in its own right. [29]

History

Women have used tampons during menstruation for thousands of years. In her book Everything You Must Know About Tampons (1981), Nancy Friedman writes, "There is evidence of tampon use throughout history in a multitude of cultures. The oldest printed medical document, Papyrus Ebers, refers to the use of soft papyrus tampons by Egyptian women in the 15th century BCE. Roman women used wool tampons. Women in ancient Japan fashioned tampons out of paper, held them in place with a bandage, and changed them 10 to 12 times a day. Traditional Hawaiian women used the furry part of a native fern called hapu'u; and grasses, mosses and other plants are still used by women in parts of Asia."[30]

R. G. Mayne defined a tampon in 1860 as: "a less inelegant term for the plug, whether made up of portions of rag, sponge, or a silk handkerchief, where plugging the vagina is had recourse to in cases of hemorrhage."[31]

Dr. Earle Haas patented the first modern tampon, Tampax, with the tube-within-a-tube applicator. Gertrude Schulte Tenderich (née Voss) bought the patent rights to her company trademark Tampax and started as a seller, manufacturer, and spokesperson in 1933.[32] Tenderich hired women to manufacture the item and then hired two sales associates to market the product to drugstores in Colorado and Wyoming; and nurses to give public lectures on the benefits of the creation; and was also instrumental in inducing newspapers to run advertisements.

In 1945, Tampax presented a number of studies to prove the safety of tampons. A 1965 study by the Rock Reproductive Clinic stated that the use of tampons "has no physiological or clinical undesired side effects".[9]

During her study of female anatomy, German gynecologist Dr. Judith Esser-Mittag developed a digital-style tampon, which was made to be inserted without an applicator. In the late 1940s, Dr. Carl Hahn, together with Heinz Mittag, worked on the mass production of this tampon. Dr. Hahn sold his company to Johnson and Johnson in 1974.[33]

Society and culture

Tampon tax

Several political statements have been made in regards to tampon use. In 2000, a 10% goods and services tax (GST) was introduced in Australia. While lubricant, condoms, incontinence pads and numerous medical items were regarded as essential and exempt from the tax, tampons continue to be charged GST. Prior to the introduction of GST, several states also applied a luxury tax to tampons at a higher rate than GST. Specific petitions such as "Axe the Tampon Tax" have been created to oppose this tax, although no change has been made.[34]

In the UK, tampons are subject to value added tax (VAT) at a reduced rate of 5%, as opposed to the standard rate of 20% applied to the vast majority of products sold in the country.[35] The relevant EU legislation was finally changed in 2016.[36] In March 2016, Parliament created legislation to eliminate the tampon VAT.[37][38] It was expected to go into effect by April 2018 but did not do so.[39] On the 3rd October 2018, new EU VAT rules that will allow the UK to stop taxing sanitary products were approved by the European Parliament. [40]

In Canada, the federal government has removed the Goods and services tax (GST) and Harmonized sales tax (HST) from tampons and other feminine hygiene products as of July 1st, 2015.[41]

Etymology

Historically, the word "tampon" originated from the medieval French word "tampion", meaning a piece of cloth to stop a hole, a stamp, plug, or stopper.[42]

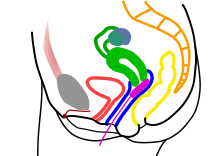

Virginity

Use of a tampon could stretch or break the hymen. Since some cultures regard preservation of the hymen as a supposed evidence of virginity (see also virginity test), this can discourage young women from using tampons.

See also

- Cloth menstrual pad

- Menstrual cup

- Sanitary napkin

- Tamponade

References

- Nicole, Wendee (March 2014). "A Question for Women's Health: Chemicals in Feminine Hygiene Products and Personal Lubricants". Environmental Health Perspectives. 122 (3): A70–5. doi:10.1289/ehp.122-A70. PMC 3948026. PMID 24583634. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Tampons". Palo Alto Medical Foundation. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "Using Tampons: Facts And Myths". SteadyHealth. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- Lynda Madaras (8 June 2007). What's Happening to My Body? Book for Girls: Revised Edition. Newmarket Press. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-1-55704-768-7.

- "Pain While Inserting A Tampon". Steadyhealth.com. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "Tampons for menstrual hygiene: Modern products with ancient roots" (PDF). Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "Tampon Absorbency Ratings - Which Tampon is Right for You". Pms.about.com. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "Data" (PDF). www.ahpma.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Delaney, Janice; Lupton, Mary Jane; Toth, Emily (1988). The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252014529.

- "A new generation faces toxic shock syndrome". The Seattle Times. January 26, 2005.

- Lanes, Stephan F.; Rothman, Kenneth J. (1990). "Tampon absorbency, composition and oxygen content and risk of toxic shock syndrome". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 43 (12): 1379–1385. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(90)90105-X. ISSN 0895-4356.

- Ross, R. A.; Onderdonk, A. B. (2000). "Production of Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin 1 by Staphylococcus aureus Requires Both Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide". Infection and Immunity. 68 (9): 5205–5209. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.9.5205-5209.2000. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC 101779. PMID 10948145.

- "e-CFR: Title 21: Food and Drugs Administration". Code of Federal Regulations. Section 801.430: User labeling for menstrual tampons: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Kent, Ellie (2019-02-07). "'I nearly died from toxic shock syndrome and never used a tampon'". BBC Three. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- "TSS: Continuing Professional Development". Toxic Shock Syndrome Information Service. 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- Mosanya, Lola (2017-02-14). "'Recognising the symptoms of toxic shock syndrome saved my life'". BBC Newsbeat. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- "Toxic Shock Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2015-02-11. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- "What You Need To Know About Toxic Shock Syndrome". University of Utah Health. 2018-07-02. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- Lindsey, Emma (6 November 2003). "Welcome to the cotton club". The Guardian – via The Guardian.

- "Ask John".

- Zespoł Ekspertów Polskiego Towarzystwa Ginekologicznego (2012). "Statement of the Polish Gynecological Society Expert Group on the use of ellen probiotic tampon". Ginekol. Pol. (in Polish). 83 (8): 633–8. PMID 23342891.

- "Markets absorbed by probiotic Swedish tampons". The Local. 2009-12-03. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

- Rastogi, Nina (2010-03-16). "What's the environmental impact of my period?". Slate.com. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- Park, Chung Hee; Kang, Yun Kyung; Im, Seung Soon (2004-09-15). "Biodegradability of cellulose fabrics". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 94 (1): 248–253. doi:10.1002/app.20879. ISSN 1097-4628.

- "How Reusable Tampons Work". Elite Daily.

- Sanghani, Radhika (3 June 2015). "Period nappies: The only new sanitary product in 45 years. Seriously - Telegraph". Telegraph.co.uk.

- Kirstie McCrum (4 June 2015). "Could 'period-proof pants' spell the end for tampons and sanitary towels?". mirror.

- Spinks, Rosie (2015-04-27). "Disposable tampons aren't sustainable, but do women want to talk about it?". the Guardian.

- "The Environmental Impact of Everyday Things". The Chic Ecologist. 2010-04-05.

- Who invented tampons? June 6, 2006 The Straight Dope

- Mayne, R. G. (1860). An Expository Lexicon of the Terms, Ancient and Modern, in Medical and General Science including a Complete Medico-Legal Vocabulary. London: John Churchill. p. 1249.

- A Short History of Periods

- "Johnson & Johnson History". Funding Universe. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Orr, Aleisha (February 22, 2013). "Tampon tax a 'bloody outrage'". WAtoday. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- Butterly, Amelia. "Why the 'tampon tax' is here to stay - for a while at least". Newsbeat. BBC. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- "Deal reached 'to scrap tampon tax'". BBC News. 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- Mortimer,, Caroline (March 21, 2016). "Tampon tax: David Cameron announces end to vat on sanitary products in House of Commons". The Independent. Retrieved October 2, 2017.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- White, Catriona (December 8, 2016). "Five women who aren't on Wikipedia but should be". BBC Three (online). Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- Larimer, Sarah (January 8, 2016). "The 'tampon tax,' explained". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Nosheena Mobarik (3 October 2018). "Mobarik: UK one step closer to ending the tampon tax". Conservatives in the European Parliament.

- "Federal government taking the tax off tampons and other feminine hygiene products, effective July 1". National Post. 2015-05-28. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- "Oxford Dictionaries - Dictionary, Thesaurus, & Grammar".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tampon. |