XY gonadal dysgenesis

XY gonadal dysgenesis, also known as Swyer syndrome, is a type of hypogonadism in a person whose karyotype is 46,XY. They typically have normal female external genitalia, identify as female, and are raised as girls.[1]

| XY gonadal dysgenesis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Swyer syndrome |

| |

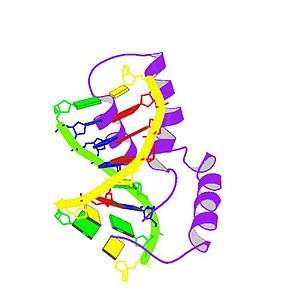

| Protein SRY | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

The person is externally female with streak gonads, and if left untreated, will not experience puberty. Such gonads are typically surgically removed (as they have a significant risk of developing cancer). The typical medical treatment is hormone replacement therapy.[2] The syndrome was named after Gerald Swyer, an endocrinologist, based in London.

Signs and symptoms

People with Swyer syndrome are born with the appearance of a normal female in most anatomic respects except that the child has nonfunctional streak gonads instead of ovaries or testes. As their ovaries produce no important body changes before puberty, a defect of the reproductive system typically remains unsuspected until puberty fails to occur. They appear to be normal girls and are generally considered so.

The consequences of Swyer syndrome without treatment:

- Gonads cannot make estrogen, so the breasts will not develop and the uterus will not grow and menstruate until estrogen is administered. This is often given transdermally.

- Gonads cannot make progesterone, so menstrual periods will not be predictable until progestin is administered, usually as a pill.

- Gonads cannot produce eggs so conceiving children is not possible without intervention. A woman with a uterus and ovaries but without female gamete is able to become pregnant by implantation of another woman's fertilized egg (embryo transfer).

- Streak gonads with Y chromosome-containing cells have a high likelihood of developing cancer, especially gonadoblastoma.[3] Streak gonads are usually removed within a year or so of diagnosis since the cancer can begin during infancy.

Genetics

Genetic associations of Swyer syndrome include:

| Type | OMIM | Gene | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete, SRY-related | 400044 | SRY | Yp11.3 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete or partial, DHH-related | 233420 | DHH | 12q13.1 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete or partial, with or without adrenal failure | 612965 | NR5A1 | 9q33 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete, CBX2-related | 613080 | CBX2 | 17q25 |

| 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis, complete or partial, with 9p24.3 deletion | 154230 | DMRT1/2 | 9p24.3 |

Seven other genes have been identified with probable associations that are as-yet less clearly understood.[4]

Pure gonadal dysgenesis

There are several forms of gonadal dysgenesis. The term "pure gonadal dysgenesis" (PGD) has been used to describe conditions with normal sets of sex chromosomes (e.g., 46,XX or 46,XY), as opposed to those whose gonadal dysgenesis results from missing all or part of the second sex chromosome. The latter group includes those with Turner syndrome (i.e., 45,X) and its variants, as well as those with mixed gonadal dysgenesis and a mixture of cell lines, some containing a Y chromosome (e.g., 46,XY/45,X).

Thus Swyer syndrome is referred to as PGD, 46,XY, and XX gonadal dysgenesis as PGD, 46,XX.[5] People with PGD have a normal karyotype but may have defects of a specific gene on a chromosome.

Pathogenesis

The first known step of sexual differentiation of a normal XY fetus is the development of testes. The early stages of testicular formation in the second month of gestation requires the action of several genes, of which one of the earliest and most important is SRY, the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome. Mutations of SRY account for many cases of Swyer syndrome.

When such a gene is defective, the indifferent gonads fail to differentiate into testes in an XY (genetically male) fetus. Without testes, no testosterone or antimüllerian hormone (AMH) is produced. Without testosterone, the wolffian ducts fail to develop, so no internal male organs are formed. Also, the lack of testosterone means that no dihydrotestosterone is formed and consequently the external genitalia fail to virilize, resulting in normal female genitalia. Without AMH, the Müllerian ducts develop into normal internal female organs (uterus, fallopian tubes, cervix, vagina).

Diagnosis

Due to the inability of the streak gonads to produce sex hormones (both estrogens and androgens), most of the secondary sex characteristics do not develop. This is especially true of estrogenic changes such as breast development, widening of the pelvis and hips, and menstrual periods. As the adrenal glands can make limited amounts of androgens and are not affected by this syndrome, most of these persons will develop pubic hair, though it often remains sparse.

Evaluation of delayed puberty usually reveals elevation of gonadotropins, indicating that the pituitary is providing the signal for puberty but the gonads are failing to respond. The next steps of the evaluation usually include checking a karyotype and imaging of the pelvis. The karyotype reveals XY chromosomes and the imaging demonstrates the presence of a uterus but no ovaries (the streak gonads are not usually seen by most imaging). Although an XY karyotype can also indicate a person with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, the absence of breasts, and the presence of a uterus and pubic hair exclude the possibility. At this point it is usually possible for a physician to make a diagnosis of Swyer syndrome.

Related conditions

Swyer syndrome represents one phenotypic result of a failure of the gonads to develop properly, and hence is part of a class of conditions termed gonadal dysgenesis. There are many forms of gonadal dysgenesis.

Swyer syndrome is an example of a condition in which an externally unambiguous female body carries dysgenetic, atypical, or abnormal gonads. Other examples include complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, partial X chromosome deletions, lipoid congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and Turner syndrome.

Treatment

Upon diagnosis, estrogen and progestogen therapy is typically commenced, promoting the development of female characteristics.

Epidemiology

It has been estimated that the incidence of Swyer syndrome is approximately 1 in 100,000 people.[6] Fewer than 100 cases have been reported as of 2018.[6] There are extremely rare instances of familial Swyer syndrome.[6]

History

Swyer syndrome was first described by Gim Swyer in 1955 in a report of two cases.[6]

References

- Reference, Genetics Home. "Swyer syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Massanyi EZ1; Dicarlo HN; Migeon CJ; Gearhart JP (29 December 2012). "Review and management of 46,XY disorders of sex development". J Pediatr Urol. 9 (3): 368–379. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.12.002. PMID 23276787.

- Eh, Zheng; Liu, Weili (June 1994). "A familial 46 XY gonadal dysgenesis and high incidence of embryonic gonadal tumors". Chinese Journal of Cancer Research. 6 (2): 144–148. doi:10.1007/BF02997250. Originally published in Chinese as PMID 7307902

- Kremen J; Chan YM; Swartz JM (January 2017). "Recent findings on the genetics of disorders of sex development". Curr Opin Urol. 27 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000353. PMC 5877806. PMID 27798415.

- Specific disorders of ambiguous genitalia

- Banoth M, Naru RR, Inamdar MB, Chowhan AK (May 2018). "Familial Swyer syndrome: a rare genetic entity". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 34 (5): 389–393. doi:10.1080/09513590.2017.1393662. PMID 29069951.

Further reading

- Stoicanescu D, Belengeanu V, et al. (2006). "Complete gonadal dysgenesis with XY chromosomal constitution". Acta Endocrinologica (Buc). 2 (4): 465–70. doi:10.4183/aeb.2006.465.

External links

| Classification |

|---|