String galvanometer

The string galvanometer, also known as the Einthoven galvanometer, invented around 1901 by Dutch physician Willem Einthoven was the first practical electrocardiograph (ECG); it was one of the earliest instruments capable of detecting and recording the very small electric currents produced by the human heart and produced the first reliable electrocardiograms. The original machines achieved "such amazing technical perfection that many modern day electrocardiographs do not attain equally reliable and undistorted recordings".[1] Einthoven was awarded the 1924 Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work.

History

Previous to the string galvanometer, scientists were using a machine called the capillary electrometer to measure the heart’s electrical activity, but this device was unable to produce results of a diagnostic level.[2] Willem Einthoven invented the string galvanometer at Leiden University in the early 20th century, publishing the first registration of its use to record an electrocardiogram in a Festschrift book in 1902. The first human electrocardiogram was recorded in 1887, however it was not until 1901 that a quantifiable result was obtained from the string galvanometer.[3] In 1908, the physicians Arthur MacNalty, M.D. Oxon, and Thomas Lewis teamed to become the first of their profession to apply electrocardiography in medical diagnosis. Einthoven was awarded the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1924 for his work.[4]

Mechanics

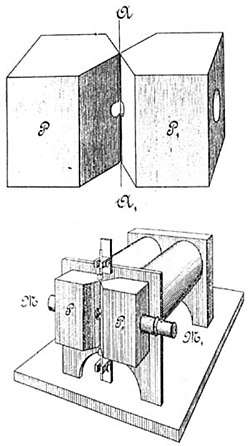

Einthoven's invention consisted of a silver-coated quartz filament of a few centimeters (see picture on the right) and negligible mass that conducted the electrical currents from the heart. This filament was acted upon by powerful electromagnets positioned either side of it, which caused sideways displacement of the filament in proportion to the current carried due to the electromagnetic field. The movement in the filament was heavily magnified and projected through a thin slot onto a moving photographic plate.[1][5]

The filament was originally made by drawing out a filament of glass from a crucible of molten glass. To produce a sufficiently thin and long filament an arrow was shot across the room so that it dragged the filament from the molten glass. The filament so produced was then coated with silver to provide the conductive pathway for the current.[6] By tightening or loosening the filament it is possible to very accurately regulate the sensitivity of the galvanometer.[1]

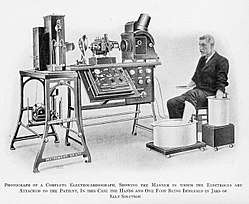

The original machine required water cooling for the powerful electromagnets, required 5 operators[7] and weighed some 600 lb.[5]

Procedure

Patients are seated with both arms and left leg in separate buckets of saline solution. These buckets act as electrodes to conduct the current from the skin's surface to the filament. The three points of electrode contact on these limbs produces what is known as Einthoven's triangle, a principle still used in modern-day ECG recording.[8]

References

- 'Willem Einthoven and the Birth of Clinical Electrocardiography a Hundred Years Ago', S. Serge Barold, Cardiac Electrophysiology Review, Springer Netherlands January 2003

- 'Einthoven's String GalvanometerThe First Electrocardiograph', Moises Rivera-Ruiz et al, Tex Heart Inst J. © 2008 by the Texas Heart Institute

- Bowbrick, S.; Borg, A.N. (2006). ECG Complete. Elsevier Limited. p. 2.

- Bowbrick & Borg (2006), p. 10.

- Einthoven (1901)

- A History of Electrocardiography pg 112-113

- NIH Archived 2008-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Bowbrick & Borg (2006), pp. 9–10.