Social determinants of health

The social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions that influence individual and group differences in health status.[1] They are the health promoting factors found in one's living and working conditions (such as the distribution of income, wealth, influence, and power), rather than individual risk factors (such as behavioral risk factors or genetics) that influence the risk for a disease, or vulnerability to disease or injury. The distributions of social determinants are often shaped by public policies that reflect prevailing political ideologies of the area.[2] The World Health Organization says, "This unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a 'natural' phenomenon but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies, unfair economic arrangements [where the already well-off and healthy become even richer and the poor who are already more likely to be ill become even poorer], and bad politics."[3]

Commonly accepted determinants

There is no single definition of the social determinants of health, but there are commonalities, and many governmental and non-governmental organizations recognize that there are social factors which impact the health of individuals.

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) Europe suggested that the social determinants of health included:[4]

- The social gradient

- Stress

- Early life

- Social exclusion

- Work

- Unemployment

- Social support

- Addiction

- Food

- Transportation

In Canada, these social determinants of health have gained wide usage.[5]

- Income and income distribution

- Education

- Unemployment and job security

- Employment and working conditions

- Early childhood development

- Food insecurity[6]

- Housing

- Social exclusion/inclusion

- Social safety network

- Health services

- Aboriginal status

- Gender

- Race

- Disability

The list could be much longer. A recently published article identified several other social determinants.[7] These social determinants of health are related to health outcomes, public policy, and are easily understood by the public to impact health. They tend to cluster together – for example, those living in poverty experience a number of negative health determinants.[5]

In 2008, the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health published a report entitled "Closing the Gap in a Generation." This report identified two broad areas of social determinants of health that needed to be addressed.[3] The first area was daily living conditions, which included healthy physical environments, fair employment and decent work, social protection across the lifespan, and access to health care. The second major area was distribution of power, money, and resources, including equity in health programs, public financing of action on the social determinants, economic inequalities, resource depletion, healthy working conditions, gender equity, political empowerment, constitution of reserves[8] and a balance of power and prosperity of nations.[3]

The 2011 World Conference on Social Determinants of Health brought together delegations from 125 member states and resulted in the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health. This declaration involved an affirmation that health inequities are unacceptable, and noted that these inequities arise from the societal conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, including early childhood development, education, economic status, employment and decent work, housing environment, and effective prevention and treatment of health problems.[9]

The United States Centers for Disease Control defines social determinants of health as "life-enhancing resources, such as food supply, housing, economic and social relationships, transportation, education, and health care, whose distribution across populations effectively determines length and quality of life".[10] These include access to care and resources such as food, insurance coverage, income, housing, and transportation.[10] Social determinants of health influence health-promoting behaviours, and health equity among the population is not possible without equitable distribution of social determinants among groups.[10]

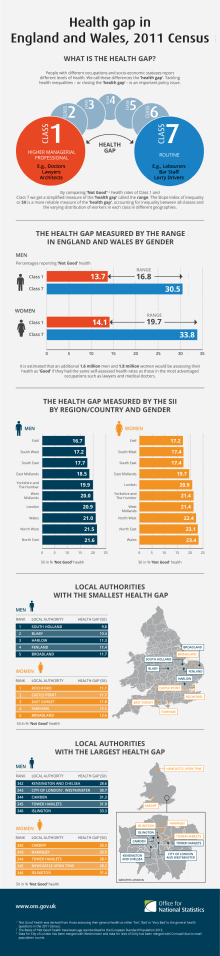

Steven H. Woolf, MD of the Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Human Needs states, "The degree to which social conditions affect health is illustrated by the association between education and mortality rates".[11] Reports in 2005 revealed the mortality rate was 206.3 per 100,000 for adults aged 25 to 64 years with little education beyond high school, but was twice as great (477.6 per 100,000) for those with only a high school education and 3 times as great (650.4 per 100,000) for those less educated. Based on the data collected, the social conditions such as education, income, and race were dependent on one another, but these social conditions also apply to independent health influences.[11]

Marmot and Bell of the University College London found that in wealthy countries, income and mortality are correlated as a marker of relative position within society, and this relative position is related to social conditions that are important for health including good early childhood development, access to high quality education, rewarding work with some degree of autonomy, decent housing, and a clean and safe living environment. The social condition of autonomy, control, and empowerment turns are important influences on health and disease, and individuals who lack social participation and control over their lives are at a greater risk for heart disease and mental illness.[12]

International health inequalities

Even in the wealthiest countries, there are health inequalities between the rich and the poor.[4] Researchers Labonte and Schrecker from the Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine at the University of Ottawa emphasize that globalization is key to understanding the social determinants of health, and as Bushra (2011) posits, the impacts of globalization are unequal.[13] Globalization has caused an uneven distribution of wealth and power both within and across national borders, and where and in what situation a person is born has an enormous impact on their health outcomes. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found significant differences among developed nations in health status indicators such as life expectancy, infant mortality, incidence of disease, and death from injuries.[14] Migrants and their family members also experience significant negatives health impacts.[15]

These inequalities may exist in the context of the health care system, or in broader social approaches. According to the WHO's Commission on Social Determinants of Health, access to health care is essential for equitable health, and it argued that health care should be a common good rather than a market commodity.[3] However, there is substantial variation in health care systems and coverage from country to country. The Commission also calls for government action on such things as access to clean water and safe, equitable working conditions, and it notes that dangerous working conditions exist even in some wealthy countries.[3][16] In the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health, several key areas of action were identified to address inequalities, including promotion of participatory policy-making processes, strengthening global governance and collaboration, and encouraging developed countries to reach a target of 0.7% of gross national product (GNP) for official development assistance.[9]

Theoretical approaches

The UK Black and The Health Divide reports considered two primary mechanisms for understanding how social determinants influence health: cultural/behavioral and materialist/structuralist[17] The cultural/behavioral explanation is that individuals' behavioral choices (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use, diet, physical activity, etc.) were responsible for their development and deaths from a variety of diseases. However, both the Black and Health Divide reports found that behavioral choices are determined by one's material conditions of life, and these behavioral risk factors account for a relatively small proportion of variation in the incidence and death from various diseases.

The materialist/structuralist explanation emphasizes the people's material living conditions. These conditions include availability of resources to access the amenities of life, working conditions, and quality of available food and housing among others. Within this view, three frameworks have been developed to explain how social determinants influence health.[18] These frameworks are: (a) materialist; (b) neo-materialist; and (c) psychosocial comparison. The materialist view explains how living conditions – and the social determinants of health that constitute these living conditions – shape health. The neo-materialist explanation extends the materialist analysis by asking how these living conditions occur. The psychosocial comparison explanation considers whether people compare themselves to others and how these comparisons affect health and wellbeing.

A nation's wealth is a strong indicator of the health of its population. Within nations, however, individual socio-economic position is a powerful predictor of health.[19] Material conditions of life determine health by influencing the quality of individual development, family life and interaction, and community environments. Material conditions of life lead to differing likelihood of physical (infections, malnutrition, chronic disease, and injuries), developmental (delayed or impaired cognitive, personality, and social development), educational (learning disabilities, poor learning, early school leaving), and social (socialization, preparation for work, and family life) problems.[20] Material conditions of life also lead to differences in psychosocial stress.[21] When the fight-or-flight reaction is chronically elicited in response to constant threats to income, housing, and food availability, the immune system is weakened, insulin resistance is increased, and lipid and clotting disorders appear more frequently.

The materialist approach offers insight into the sources of health inequalities among individuals and nations. Adoption of health-threatening behaviours is also influenced by material deprivation and stress.[22] Environments influence whether individuals take up tobacco, use alcohol, consume poor diets, and have low levels of physical activity. Tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and carbohydrate-dense diets are also used to cope with difficult circumstances.[23][22] The materialist approach seeks to understand how these social determinants occur.

The neo-materialist approach is concerned with how nations, regions, and cities differ on how economic and other resources are distributed among the population.[24] This distribution of resources can vary widely from country to country. The neo-materialist view focuses on both the social determinants of health and the societal factors that determine the distribution of these social determinants, and especially emphasizes how resources are distributed among members of a society.

The social comparison approach holds that the social determinants of health play their role through citizens' interpretations of their standings in the social hierarchy.[25] There are two mechanisms by which this occurs. At the individual level, the perception and experience of one's status in unequal societies lead to stress and poor health. Feelings of shame, worthlessness, and envy can lead to harmful effects upon neuro-endocrine, autonomic and metabolic, and immune systems.[21] Comparisons to those of a higher social class can also lead to attempts to alleviate such feelings by overspending, taking on additional employment that threaten health, and adopting health-threatening coping behaviours such as overeating and using alcohol and tobacco.[25] At the communal level, widening and strengthening of hierarchy weakens social cohesion, which is a determinant of health.[26] The social comparison approach directs attention to the psychosocial effects of public policies that weaken the social determinants of health. However, these effects may be secondary to how societies distribute material resources and provide security to its citizens, which are described in the materialist and neo-materialist approaches.

Life-course perspective

Life-course approaches emphasize the accumulated effects of experience across the life span in understanding the maintenance of health and the onset of disease. The economic and social conditions – the social determinants of health – under which individuals live their lives have a cumulative effect upon the probability of developing any number of diseases, including heart disease and stroke.[27][28] Studies into the childhood and adulthood antecedents of adult-onset diabetes show that adverse economic and social conditions across the life span predispose individuals to this disorder.[29][30]

Hertzman outlines three health effects that have relevance for a life-course perspective.[31] Latent effects are biological or developmental early life experiences that influence health later in life. Low birth weight, for instance, is a reliable predictor of incidence of cardiovascular disease and adult-onset diabetes in later life. Nutritional deprivation during childhood has lasting health effects as well.

Pathway effects are experiences that set individuals onto trajectories that influence health, well-being, and competence over the life course. As one example, children who enter school with delayed vocabulary are set upon a path that leads to lower educational expectations, poor employment prospects, and greater likelihood of illness and disease across the lifespan. Deprivation associated with poor-quality neighbourhoods, schools, and housing sets children off on paths that are not conducive to health and well-being.[32]

Cumulative effects are the accumulation of advantage or disadvantage over time that manifests itself in poor health, in particular between women and men.[33] These involve the combination of latent and pathways effects. Adopting a life-course perspective directs attention to how social determinants of health operate at every level of development – early childhood, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood – to both immediately influence health and influence it in the future.[34][35]

Chronic stress and health

Stress is hypothesized to be a major influence in the social determinants of health. There is a relationship between experience of chronic stress and negative health outcomes.[36] This relationship is explained through both direct and indirect effects of chronic stress on health outcomes.

The direct relationship between stress and health outcomes is the effect of stress on human physiology. The long term stress hormone, cortisol, is believed to be the key driver in this relationship.[37] Chronic stress has been found to be significantly associated with chronic low-grade inflammation, slower wound healing, increased susceptibility to infections, and poorer responses to vaccines.[36] Meta-analysis of healing studies has found that there is a robust relationship between elevated stress levels and slower healing for many different acute and chronic conditions[38] However, it is also important to note that certain factors, such as coping styles and social support, can mitigate the relationship between chronic stress and health outcomes.[39][40]

Stress can also be seen to have an indirect effect on health status. One way this happens is due to the strain on the psychological resources of the stressed individual. Chronic stress is common in those of a low socio-economic status, who are having to balance worries about financial security, how they will feed their families, housing status, and many other concerns.[41] Therefore, individuals with these kinds of worries may lack the emotional resources to adopt positive health behaviours. Chronically stressed individuals may therefore be less likely to prioritize their health.

In addition to this, the way that an individual responds to stress can influence their health status. Often, individuals responding to chronic stress will develop potentially positive or negative coping behaviors. People who cope with stress through positive behaviors such as exercise or social connections may not be as affected by the relationship between stress and health, whereas those with a coping style more prone to over-consumption (i.e. emotional eating, drinking, smoking or drug use) are more likely to be see negative health effects of stress.[39]

The detrimental effects of stress on health outcomes are hypothesised to partly explain why countries that have high levels of income inequality have poorer health outcomes compared to more equal countries.[42] Wilkinson and Picket hypothesise in their book The Spirit Level that the stressors associated with low social status are amplified in societies where others are clearly far better off.[42]

Improving health conditions worldwide

Reducing the health gap requires that governments build systems that allow a healthy standard of living for every resident.

Interventions

Three common interventions for improving social determinant outcomes as identified by the WHO are education, social security and urban development. However, evaluation of interventions has been difficult due to the nature of the interventions, their impact and the fact that the interventions strongly affect children's health outcomes.[43]

- Education: Many scientific studies have been conducted and strongly suggests that increased quantity and quality of education leads to benefits to both the individual and society (e.g. improved labor productivity).[44] Health and economic outcome improvements can be seen in health measures such as blood pressure,[45][46] crime,[47] and market participation trends.[48] Examples of interventions include decreasing size of classes and providing additional resources to low-income school districts. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to support education as an social determinants intervention with a cost-benefit analysis.[43]

- Social Protection: Interventions such as “health-related cash transfers”, maternal education, and nutrition-based social protections have been shown to have a positive impact on health outcomes.[49][50] However, the full economic costs and impacts generated of social security interventions are difficult to evaluate, especially as many social protections primarily affect children of recipients.[43]

- Urban Development: Urban development interventions include a wide variety of potential targets such as housing, transportation, and infrastructure improvements. The health benefits are considerable (especially for children), because housing improvements such as smoke alarm installation, concrete flooring, removal of lead paint, etc. can have a direct impact on health.[51] In addition, there is a fair amount of evidence to prove that external urban development interventions such as transportation improvements or improved walkability of neighborhoods (which is highly effective in developed countries) can have health benefits.[43] Affordable housing options (including public housing) can make large contributions to both social determinants of health, as well as the local economy.[52]

The Commission on Social Determinants of Health made recommendations in 2005 for action to promote health equity based on three principles: "improve the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age; tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources, the structural drivers of conditions of daily life, globally, nationally, and locally; and measure the problem, evaluate action, and expand the knowledge base."[53] These recommendations would involve providing resources such as quality education, decent housing, access to affordable health care, access to healthy food, and safe places to exercise for everyone despite gaps in affluence. Expansion of knowledge of the social determinants of health, including among healthcare workers, can improve the quality and standard of care for people who are marginalized, poor or living in developing nations by preventing early death and disability while working to improve quality of life.[54]

Challenges of measuring value of interventions

Many economic studies have been conducted to measure the effectiveness and value of social determinant interventions but are unable to accurately reflect effects on public health due to the multi-faceted nature of the topic. While neither cost-effectiveness nor cost-utility analysis is able to be used on social determinant interventions, cost-benefit analysis is able to better capture the effects of an intervention on multiple sectors of the economy. For example, tobacco interventions have shown to decrease tobacco use, but also prolong lifespans, increasing lifetime healthcare costs and is therefore marked as a failed intervention by cost-effectiveness, but not cost-benefit. Another issue with research in this area is that most of the current scientific papers focus on rich, developed countries, and there is a lack of research in developing countries.[43]

Policy changes that affect children also present the challenge that it takes a significant amount of time to gather this type of data. In addition, policies to reduce child povertyare particularly important, as elevated stress hormones in children interfere with the development of brain circuitry and connections, causing long term chemical damage.[55] In most wealthy countries, the relative child poverty rate is 10 percent or less; in the United States, it is 21.9 percent.[56] The lowest poverty rates are more common in smaller well-developed and high-spending welfare states like Sweden and Finland, with about 5 or 6 percent.[56] Middle-level rates are found in major European countries where unemployment compensation is more generous and social policies provide more generous support to single mothers and working women (through paid family leave, for example), and where social assistance minimums are high. For instance, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium and Germany have poverty rates that are in the 7 to 8 percent range.[57]

Public policy

The Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health embraces a transparent, participatory model of policy development that, among other things, addresses the social determinants of health leading to persistent health inequalities for indigenous peoples.[9] In 2017, citing the need for accountability for the pledges made by countries in the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health, the World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund called for the monitoring of intersectoral interventions on the social determinants of health that improve health equity.[58]

The United States Department of Health and Human Services includes social determinants in its model of population health, and one of its missions is to strengthen policies which are backed by the best available evidence and knowledge in the field [59] Social determinants of health do not exist in a vacuum. Their quality and availability to the population are usually a result of public policy decisions made by governing authorities. For example, early life is shaped by availability of sufficient material resources that assure adequate educational opportunities, food and housing among others. Much of this has to do with the employment security and the quality of working conditions and wages. The availability of quality, regulated childcare is an especially important policy option in support of early life.[60] These are not issues that usually come under individual control but rather they are socially constructed conditions which require institutional responses.[61] A policy-oriented approach places such findings within a broader policy context. In this context, Health in All Policies has seen as a response to incorporate health and health equity into all public policies as means to foster synergy between sectors and ultimately promote health.

Yet it is not uncommon to see governmental and other authorities individualize these issues. Governments may view early life as being primarily about parental behaviours towards their children. They then focus upon promoting better parenting, assist in having parents read to their children, or urge schools to foster exercise among children rather than raising the amount of financial or housing resources available to families. Indeed, for every social determinant of health, an individualized manifestation of each is available. There is little evidence to suggest the efficacy of such approaches in improving the health status of those most vulnerable to illness in the absence of efforts to modify their adverse living conditions.[62]

A team of the Cochrane Collaboration conducted the first comprehensive systematic review of the health impact of unconditional cash transfers, as an increasingly common up-stream, structural social determinant of health. The review of 21 studies, including 16 randomized controlled trials, found that unconditional cash transfers may not improve health services use. However, they lead to a large, clinically meaningful reduction in the likelihood of being sick by an estimated 27%. Unconditional cash transfers may also improve food security and dietary diversity. Children in recipient families are more likely to attend school, and the cash transfers may increase money spent on health care.[63]

One of the recommendations by the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health is expanding knowledge – particularly to health care workers.[54]

Although not addressed by the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, sexual orientation and gender identity are increasingly recognized as social determinants of health.[64]

See also

- Adverse Childhood Experiences Study

- Causal inference

- Center for Minority Health

- Diseases of affluence

- Diseases of poverty

- Epidemiology

- EuroHealthNet

- Etiology

- Exercise

- Global health

- Health equity

- Health behaviour

- Health literacy

- Healthy People

- Inequality in disease

- Joint Action Health Equity in Europe

- Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions

- Medical anthropology

- Medical sociology

- Molecular pathological epidemiology

- Pathogenesis

- Pathology

- Population health

- Population Health Forum

- Race and health

- Social determinants of health in Mexico

- Social determinants of obesity

- Social epidemiology

- Unnatural Causes: Is Inequality Making Us Sick?

- Whitehall Study

- Michael Marmot

- Richard G. Wilkinson

- Dennis Raphael

Notes and references

- Braveman, P. and Gottlieb, L., 2014. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public health reports, 129(1_suppl2), pp.19-31.

- Mikkonen, Juha; Raphael, Dennis (2010). Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts (PDF). ISBN 978-0-9683484-1-3.

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008). Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health (PDF). World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-156370-3. Retrieved 2013-03-27. Pg 2

- Wilkinson, Richard; Marmot, Michael, eds. (2003). The Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts (PDF) (2nd ed.). World Health Organization Europe. ISBN 978-92-890-1371-0.

- Bryant, Toba; Raphael, Dennis; Schrecker, Ted; Labonte, Ronald (2011). "Canada: A land of missed opportunity for addressing the social determinants of health". Health Policy. 101 (1): 44–58. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.022. PMID 20888059.

- Arenas, Daniel J., et al. "A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Depression, Anxiety, and Sleep Disorders in US Adults with Food Insecurity." Journal of general internal medicine (2019): 1-9. || https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05202-4

- Islam, M M (2019). "Social Determinants of Health and Related Inequalities: Confusion and Implications". Front. Public Health. 7: 11. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00011. PMC 6376855. PMID 30800646.

- Cullati, Stéphane; Kliegel, Matthias; Widmer, Eric (2018-07-30). "Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life". Nature Human Behaviour. 2 (8): 551–558. doi:10.1038/s41562-018-0395-3. ISSN 2397-3374. PMID 31209322.

- World Conference on Social Determinants of Health (2011). "Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Brennan Ramirez, Laura K.; Baker, Elizabeth A.; Metzler, Marilyn (2008). Promoting Health Equity: A Resource to Help Communities Address Social Determinants of Health (PDF). United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. p. 6. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- Woolf, Steven H. (2009). "Social Policy as Health Policy". JAMA. 301 (11): 1166–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.320. PMID 19293418.

- Marmot, Michael G.; Bell, Ruth (2009). "Action on Health Disparities in the United States". JAMA. 301 (11): 1169–71. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.363. PMID 19293419.

- Labonté, Ronald; Schrecker, Ted (2007). "Globalization and social determinants of health: The role of the global marketplace (part 2 of 3)". Globalization and Health. 3: 6. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-3-6. PMC 1919362. PMID 17578569.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2007). Health at a Glance 2007, OECD Indicators. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Pg 25

- Flynn, Michael; Carreon, Tania; Eggerth, Donald; Johnson, Antoinette (2014). "Immigration, Work, and Health: A Literature Review of Immigration Between Mexico and the United States". Revista DeTrabajo Social UNAM. 7 (6): 129–149. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- Flynn, Michael (2015). "Undocumented Status as a Social Determinant of Occupational Safety and Health: The Workers' Perspective". Am. J. Ind. Med. 58 (11): 1127–1137. doi:10.1002/ajim.22531. PMC 4632487. PMID 26471878. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- Townsend, P., Davidson, N., & Whitehead, M. (Eds.). (1992). Inequalities in Health: the Black Report and the Health Divide. New York: Penguin.

- Bartley, M. (2003). Understanding Health Inequalities. Oxford UK: Polity Press.

- Graham, H. (2007). Unequal Lives: Health and Socioeconomic Inequalities. New York: Open University Press.

- Shaw, M.; Dorling, D.; Gordon, D.; Smith, G. D. (1999). The Widening Gap: Health Inequalities and Policy in Britain. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press.

- Marmot, Michael; Wilkinson, Richard G. (2005). "Social organization, stress, and health". In Marmot, Michael; Wilkinson, Richard (eds.). Social Determinants of Health. pp. 6–30. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198565895.003.02. ISBN 978-0-19-856589-5.

- Marmot, Michael; Wilkinson, Richard G. (2005). "Social patterning of individual health behaviours: The case of cigarette smoking". In Marmot, Michael; Wilkinson, Richard (eds.). Social Determinants of Health. pp. 224–37. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198565895.003.11. ISBN 978-0-19-856589-5.

- Wilkinson, R. G. (1996). Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-09234-0.

- Lynch, J. W; Smith, G. D.; Kaplan, G. A.; House, J. S. (2000). "Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions". BMJ. 320 (7243): 1200–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1200. PMC 1127589. PMID 10784551.

- Kawachi, I.; Kennedy, B. (2002). The Health of Nations: Why Inequality Is Harmful to Your Health. New York: New Press.

- Kawachi, I.; Kennedy, B. P (1997). "Socioeconomic determinants of health : Health and social cohesion: Why care about income inequality?". BMJ. 314 (7086): 1037–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7086.1037. PMC 2126438. PMID 9112854.

- Blane, D. (2006). "The life course, the social gradient and health". In Marmot, M. G.; Wilkinson, R. G. (eds.). Social Determinants of Health (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 54–77.

- Burton-Jeangros, Claudine; Cullati, Stéphane; Sacker, Amanda; Blane, David (2015), Burton-Jeangros, Claudine; Cullati, Stéphane; Sacker, Amanda; Blane, David (eds.), "Introduction", A Life Course Perspective on Health Trajectories and Transitions, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20484-0_1, ISBN 9783319204833, PMID 27683928, retrieved 2018-09-06

- Lawlor, D. A; Ebrahim, S; Davey Smith, G; British women's heart health study (2002). "Socioeconomic position in childhood and adulthood and insulin resistance: Cross sectional survey using data from British women's heart and health study". BMJ. 325 (7368): 805. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7368.805. PMC 128946. PMID 12376440.

- Raphael, Dennis; Anstice, Susan; Raine, Kim; McGannon, Kerry R.; Kamil Rizvi, Syed; Yu, Vanessa (2003). "The social determinants of the incidence and management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Are we prepared to rethink our questions and redirect our research activities?". Leadership in Health Services. 16 (3): 10–20. doi:10.1108/13660750310486730.

- Hertzman, Clyde (2000). "The case for an early childhood development strategy" (PDF). Isuma. 1 (2): 11–8.

- Raphael, Dennis (2010). Staying Alive: Critical Perspectives on Health, Illness, and Health Care. Canada: Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 159. ISBN 9781551303703.

- Landös, Aljoscha; von Arx, Martina; Cheval, Boris; Sieber, Stefan; Kliegel, Matthias; Gabriel, Rainer; Orsholits, Dan; Linden, Van Der; A, Bernadette W. (2019). "Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and disability trajectories in older men and women: a European cohort study". European Journal of Public Health. 29 (1): 50–58. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky166. PMC 6657275. PMID 30689924.

- Raphael, Dennis (2016). Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives. Canada: Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781551308975.

- Cheval, Boris; Boisgontier, Matthieu P; Orsholits, Dan; Sieber, Stefan; Guessous, Idris; Gabriel, Rainer; Stringhini, Silvia; Blane, David; van der Linden, Bernadette W A (2018-02-20). "Association of early- and adult-life socioeconomic circumstances with muscle strength in older age". Age and Ageing. 47 (3): 398–407. doi:10.1093/ageing/afy003. ISSN 0002-0729. PMID 29471364.

- Gouin, J.-P. (2011). "Chronic Stress, Immune Dysregulation, and Health". American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 5 (6): 476–85. doi:10.1177/1559827610395467.

- Miller, Gregory E.; Chen, Edith; Zhou, Eric S. (2007). "If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans". Psychological Bulletin. 133 (1): 25–45. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. PMID 17201569.

- Walburn, Jessica; Vedhara, Kavita; Hankins, Matthew; Rixon, Lorna; Weinman, John (2009). "Psychological stress and wound healing in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 67 (3): 253–71. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.002. PMID 19686881.

- Cwikel, Julie; Segal-Engelchin, Dorit; Mendlinger, Sheryl (2010). "Mothers' coping styles during times of chronic security stress: effect on health status". Health Care for Women International. 31 (2): 131–52. doi:10.1080/07399330903141245. PMID 20390642.

- Cohen, Sheldon; McKay, Garth (1984). "Social Support, Stress and the Buffering Hypothesis: A Theoretical Analysis" (PDF). In Baum, A.; Taylor, S.E.; Singer, J.E. (eds.). Handbook of Psychology and Health. pp. 253–67.

- Tengland, P.-A. (2012). "Behavior Change or Empowerment: On the Ethics of Health-Promotion Strategies". Public Health Ethics. 5 (2): 140–53. doi:10.1093/phe/phs022. hdl:2043/14851.

- Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K. (2009) The spirit level : why more equal societies almost always do better. London: Allen Lane.

- World Health Organization (2013). The economics of social determinants of health and health inequalities: a resource book (PDF). World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154862-5. retrieved 2018-04-02

- Hanushek, Eric; Woessmann, Ludger (November 2010). "The Economics of International Differences in Education Achievement". Handbook of the Economics of Education. 3 – via Elsevier.

- Cutler, David, and Adriana Lleras-Muney (2008). “Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence.” Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as HealthPolicy, edited by J House, R Schoeni, G Kaplan, and H Pollack. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Sabates, Ricardo; Feinstein, Leon (2006). "The role of education in the uptake of preventative health care: The case of cervical screening in Britain". Social Science & Medicine. 62 (12): 2998–3010. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.032. PMID 16403597.

- The Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning (2002). Quantitative Estimates of the Social Benefits of Learning 1: Crime (PDF). Department for Education and Skills, UK. ISBM 1-898453-36-5. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Canton, Erik (2007). "Social returns to education: Macro-evidence". De Economist. 155 (4): 449–468. doi:10.1007/s10645-007-9072-z.

- Chunh, Haejoo; Muntaner, Carles (2006). "Welfare state matters: A typological multilevel analysis of wealthy countries". Health Policy. 80 (2): 328–339. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.03.004. PMID 16678294.

- Economic Policy Research Institute (2004). The Social and Economic Impact of South Africa's Social Security System (PDF). Commissioned by Directorate: Finance and Economics. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- Breysse et al. (2004). The Relationship between Housing and Health: Children at Risk. Environ Health Perspect 112.15. pg 1583-1588.

- Econsult Corp (2018). The Economic Impact of Public Housing: Ongoing Investment with Wide Reaching Returns. Council of Large Public Housing Authorities.

- Marmot, Michael G.; Bell, Ruth (2009). "Action on Health Disparities in the United States". JAMA. 301 (11): 1169–71. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.363. PMID 19293419.

- Farmer, Paul E.; Nizeye, Bruce; Stulac, Sara; Keshavjee, Salmaan (2006). "Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine". PLoS Medicine. 3 (10): e449. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449. PMC 1621099. PMID 17076568.

- Evans, G. W.; Schamberg, M. A. (2009). "Childhood poverty, chronic stress, and adult working memory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (16): 6545–9. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.6545E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811910106. JSTOR 40482133. PMC 2662958. PMID 19332779.

- Smeeding, Timothy (2006). "Poor People in Rich Nations: The United States in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 20: 69–90. doi:10.1257/089533006776526094. hdl:10419/95383.

- Smeeding, Timothy (2006). "Poor People in Rich Nations: The United States in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 20 (1): 69–90. doi:10.1257/089533006776526094. hdl:10419/95383. JSTOR 30033634.

- Pega, Frank; Valentine, Nicole; Rasanathan, Kumanan; Hosseinpoor, Ahmad Reza; Neira, Maria (2017). "The need to monitor actions on the social determinants of health". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 95 (11): 784–787. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.184622. PMC 5677605. PMID 29147060.

- "Healthy People 2020 Framework" (PDF). United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-15. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (2002). "A Child-Centred Social Investment Strategy". In Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (ed.). Why We Need a New Welfare State. pp. 26–67. ISBN 978-0-19-925642-6.

- Flynn, Michael; Check, Pietra; Eggerth, Donald; Tonda, Josana (2013). "Improving Occupational Safety and Health Among Mexican Immigrant Workers". Public Health Reports. 128 (Suppl 3): 33–38. doi:10.1177/00333549131286S306. PMC 3945447. PMID 24179277.

- Raphael, D. (2001). Inequality is Bad for our Hearts: Why Low Income and Social Exclusion are Major Causes of Heart Disease in Canada. ISBN 978-0-9689444-0-0.

- Pega, Frank; Liu, Sze; Walter, Stefan; Pabayo, Roman; Saith, Ruhi; Lhachimi, Stefan (2017). "Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD011135. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011135.pub2. PMC 6486161. PMID 29139110.

- Pega, Frank; Veale, Jaimie (2015). "The case for the World Health Organization's Commission on Social Determinants of Health to address gender identity". American Journal of Public Health. 105 (3): e58–62. doi:10.2105/ajph.2014.302373. PMC 4330845. PMID 25602894.

External links

- The determinants of health (World Health Organization)

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health (World Health Organization)

- A glossary for social epidemiology - N Krieger

- Key determinants of health (Public Health Agency of Canada)

- NPTEL - Socio-economic Status and Health Income Inequality and Health

- Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts

- The Social Context of Health Behaviors - Paula Braveman

- World Health Organization: Equity, Social Determinants and Public Health Programmes

- Public Health Agency of Canada: What determines health? - Key determinants

- Drivers for Health Equity